Family life

Richard Law, UTC 2016-12-09 06:43

Marie von Spaun: join the queue

Even more fatal for the theory of repressed homosexuality is the fact that so many of the boys in Kremsmünster fell helplessly in love with Marie von Spaun (1795-1847), Joseph and Anton's sister. The adolescent Schober was paralysed with desire for quite some time, his energy completely sapped by swirling emotions.

A classmate of Schober's reported the drama in a letter, presumably to Anton von Spaun. The letter is preserved in Schober's obsessively archived collection of the documents of his life, yet, as with a number of other documents, his own name and some of the names of others have been scratched out. We leave it to our team of psychiatric advisors to tell us why someone would preserve a document and then go to such trouble obliterating parts of it. A suitable case for treatment, indeed.

[We had all] noticed that he [Schober] was in love with your sister Marie. In a pleasant moment of friendship I got him to admit this. But just as when you breach a dam and are suddenly overwhelmed by water, out of his breast burst lamentations, tears, sighs, over hopeless love, over age differences, over competitors such as Ottenwalt, Kenner, Kreil. I had to comfort him (and Ottenwalt must forgive me, that I forgot his rule never to let love get the upper hand in Schober's heart).

Quoted in Steblin Marie von Spaun p. 64.

Marie seems to have reciprocated his affections, or at least egged the handsome boy on. The ultimately futile nature of the relationship probably made things much worse for the young lad writhing in Belial's gripe.

We have a careful assessment of Schober in his Kremsmünster years written by Anton von Spaun (it is presumed). The account was written in later years, in full knowledge of the later Schober, but seems to be fair and honest:

When I first saw him, he seemed to me to be a cheerful, handsome, fine lad, very knowledgable for his age,…

He was not much interested in learning, as a result his school reports were poor, even though in all the most important things he was better than the best in the school. As a result, in his youth he acquired a certain indifference to all forms and rules, which later, applied to all rules and laws, had great influence on the development of his character.

Quoted in Waidelich Torupson p. 30.

The 'deeply depraved family'

We cannot get much further with our disentangling of Schober's life and his importance for Schubert without considering the rest of the Schober family and particularly the females: his widowed mother Katharina (1762-1833) and Franz's two older sisters Ludovica von Schober (1790-1812) and Sophie von Schober (1795-1825). At the time of the family's relocation to Vienna after Franz Xaver's early death his mother Katharina was forty, Ludovica thirteen and Sophie eight (these ages are not accurate to the month, since we don't know exactly when the Schobers arrived in Vienna).

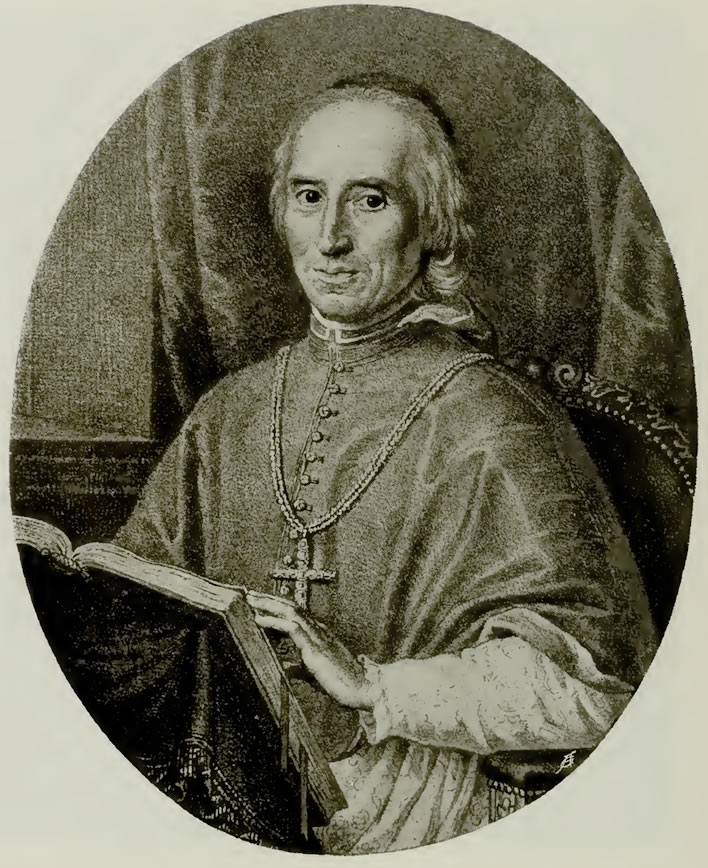

Katharina may ultimately have been a rich woman, but, as we have already noted, her late husband's wealth took its time getting from Sweden to Vienna. She was not alone in Vienna: her relatives, the Derffels, formed a large extended family, but it was nevertheless difficult for a single woman at the time not to have a male protector in some form or other. She found hers in the Suffragan Bishop Johann Nepomuk von Dankesreither (1750-1823). After Franz Xaver's death he took her under his wing – and under his cassock, too, it seems. We imagine that her rapid return to Vienna may even have been on his account and facilitated by him.

Suffragan Bishop Johann Nepomuk von Dankesreither (1750-1823) [ND]. Lithograph by Johann Lanzedelly from a painting by Josef Pfeiffer. Hofbibliothek, Vienna.

We here are not censorious about this mutually beneficial relationship between two mature adults, but the secret police of those paranoid times took a prurient interest in the relationship. That's what secret police do. In those days they were as much a moral police as a political or criminal police.

As far as we can gather – many of the records concerning this case and many others were destroyed in the arson at the Viennese Palace of Justice during the revolutionary days of 1927 – it was Ludovica, the eldest daughter, who had attracted the attention of the secret police, who employed an army of paid narks and 'bluebottles' to supply them with information.

The greatest concerns of Franz II/I's secret police were the activities of the foreigners in Austria and particularly the French diplomats and exiles. Juicy young Ludovica, the granddaughter of the spa hotel owner in Baden, was passed around – putting it rather coarsely but accurately – among the louche French aristocrats taking the waters in Baden, with, 'among others', the Secretary of the French Embassy and a doctor from Lemberg in Germany, Friedrich Oloff, whose passionate love letters to Ludovica were intercepted and transcribed. The police also found out that a Pole, Count Kasimir Otocki, whom they suspected of pimping, had consumed an excellent breakfast paid for by a certain Herr von Zaborowski after introducing Ludovica to him. Ludovica seems to have hidden her activities from her mother because, as someone so wisely remarked: 'girls just want to have fun, fun, fun'. Opportunities were found for the mother to return to her bishop in Vienna and the daughter to take the waters in Baden with her admirers. The secret police wrote it all down, as secret police officers do. They observed her so intently that they were able to form a picture of the type of man to which she was attracted. There were no flies on the 'bluebottles' and historians are extremely grateful to them.

Brief bliss with her tenor

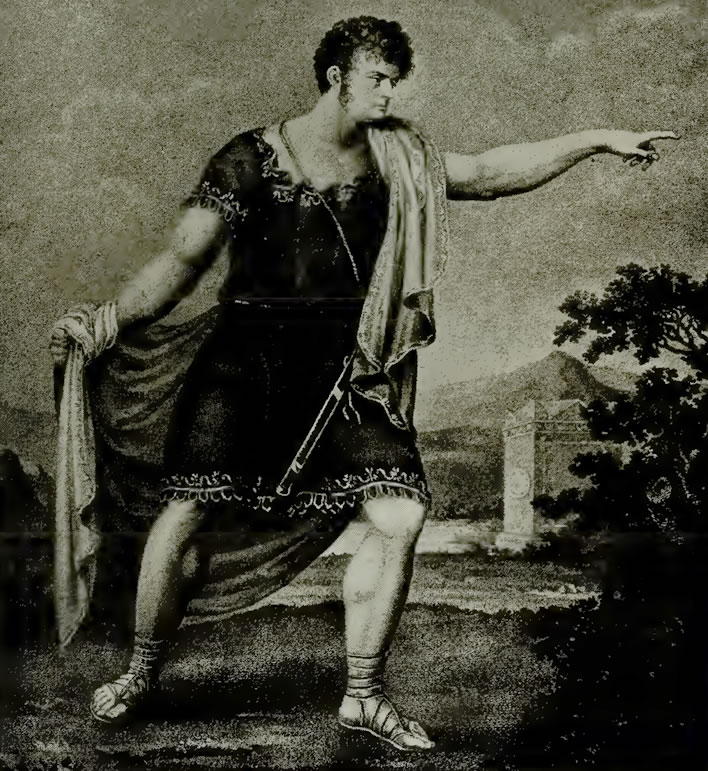

Ludovica had a tender heart, one that was overcome with passion when she saw the Italian tenor Giuseppe Siboni (1780-1839) perform in the Viennese Court Opera in 1811. He seems to have been exactly the type that turned her on. She determined to get him and get him she did, in remarkably short order, too. She broke off her engagement to another man – which the rejected one may have later considered to be a 'dodged bullet' – and 'acquired' Siboni. They married on 4 July 1811. Marital bliss did not last long for poor Ludovica.

Giuseppe Siboni as Licinius in Gaspare Spontini's Opera Die Vestalin. Engraving by David Weiß (1813) after a drawing by Ludovica Siboni, née von Schober.

On 23 November 1812 she was killed whilst 'cleaning a pistol'. Despite the clear autopsy results indicating an accident, the story of the event is so bizarre that rumours of either suicide or murder would have spread rapidly through the salons of the chattering classes of that gossipy city. Ludovica was cleaning the pistol, she dismantled it, held the barrel up to the candle to inspect it, then blew down it. There was still gunpowder in the barrel, which went off when the barrel was in her mouth. The force of the explosion shredded her tongue, almost ripped her jaw off and burst the surrounding blood vessels in her neck, causing her to bleed to death within moments.

There was no trace of a projectile in her mouth. Her husband was not in the room at the time, but the authorities found him wildly distraught as only an Italian tenor can be distraught. The police had the same difficulty as we do in believing the events of the incident and referred the case for reappraisal and a second autopsy, but no evidence implicating Siboni was ever found. Why would anyone even attempt to murder someone or commit suicide with a pistol without a bullet? Why would any well brought-up woman be cleaning a pistol anyway? Accident or not, this kind of thing was not what should happen in a well-regulated, bourgeois Viennese family.

These police reports were not public, but tongues wagged. It has even been suggested that some or all of Katharina's children were not poor old workaholic Franz Xaver Schober's but Baron Alexius von Stiernblad's, whose patronage both Axel (his godson – Alexius/Axel, geddit?) and Franz von Schober had to thank for getting them into the Salzmann school. Idle gossip without any foundation, unfortunately passed on in several biographies, which of course do not name their sources for this information. Where are the narks and 'bluebottles' of the secret police when they are needed?

Domenico Bossi (1765-1853), portrait Miniature of Baron Axel von Stiernblad, 1793. (op cit)

Mud sticks, it seems: when Siboni applied for Austrian citizenship in 1816, despite positive preliminary reports, his application was rejected. Unfortunately, the files containing that rejection were lost in the 1927 fire. Just one more puzzle, one more knot in the string.

Losing Marie

Back to Ludovica's brother Franz Schober, the hero of our tale. There is some evidence that Schober's character was slandered during his time in Kremsmünster, whether because of the Selbstbefleckung affair or some other incidents about which we have no knowledge. But, whether truth or slander, we can draw the reasonable conclusion that Schober's reputation at the school was not impeccable. Let us not forget that Marie's mother, the widowed Josefa von Spaun, had already developed a good eye for spotting a bad one in the case of her brother-in-law Franz Seraph Spaun.

It is Joseph von Spaun in his 'Family Chronicle' who tells us of his mother Josefa's opposition to Franz Schober marrying her daughter Marie. According to Joseph this was solely because of her feeling that Schober was not religious. Spaun does not expand on this point, but we can imagine that growing up in soundly Protestant Sweden and attending a school in soundly Protestant Thuringia added to Schober's outsider status in a Benedictine school in soundly Catholic Austria. Some religious indifference on Schober's part should not really surprise us, but we have here just another one of those Schober puzzles: Among all his his other mediocre marks at Kremsmünster he attained top marks in Doctrina Religion. Bang goes another theory – or perhaps he was just swotting so that he could impress Josefa in the next interrogation.

That may have been the reason Josefa gave to Marie, but Joseph von Spaun – lawyer, high civil servant, always precise, always avoiding the tittle-tattle we all enjoy, who even criticised Schubert's first biographer for mentioning personal matters – goes out of his way to rule out all other unspecific things:

My mother would have not objected to any other trait, but believed she had to suppress this one. She believed, from Schober's behaviour and many conversations, that Schober was not religious; she therefore came to the conclusion that a closer relationship with Schober would make her daughter unhappy and believed it to be her duty to tell her daughter, naming these reasons, that she regarded a closer relationship with Schober for out of the question and that she therefore had to forbid this.

Quoted in Steblin Marie von Spaun p. 65.

Spaun, normally so clear a writer, descends here into a strangulated prose which suggests a degree of embarrassment on his part. We can imagine poor Schober, with so much Protestantism in his head, not surviving the gimlet-eyed interrogation of the formidable Josefa on the finer points of Catholic doctrine, but by this time, around 1814, the whole Schober family in Vienna was, as we have seen, the subject of gossip. For the chattering classes, Vienna was really just a village.

There was his sister Ludovica's marriage to an Italian opera singer – not one of the most respectable professions in the Empire – followed so shortly by that mysterious accident with a pistol in which she died. We can scarcely doubt that the close affiliation of Schober's mother with Bishop Dankesreither wasn't common knowledge. Until quite recently, prudish writers have been happy to assume that he was a relative of the Schobers – Dankesreither was, after all, a supposedly celibate Catholic bishop – but this is not the case. Furthermore, the watering places in Baden would have known all about Ludovica's complicated life there. We are just curious to find out what things little Sophie got up to. The pile of silver left behind by poor old Franz Xaver Schober could buy you everything – except a good reputation.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Sophie Schober, pencil drawing, c. 1821.

The suppression of a closer relationship between Schober and Marie had led for a while from 1814 onwards to his bitter rejection of the Spaun brothers, particularly Joseph and Anton. We hear the outsider Schober, who had thought he was 'one of them', now lament that he had 'never received real friendship' in Kremsmünster. But after he returned from his Sweden trip in 1816, his head now seemingly cleared of Marie, a reconciliation with the brothers and his former Kremsmünster friends took place.

If we read Joseph von Spaun's words carefully, we note that Josefa's ban forbade taking the relationship further. It did not require a separation or an end to the pair's friendship. Franz Schober and Marie von Spaun kept in touch until about 1816, when both finally moved in other directions: she married another of the Kremsmünster boys who had dreamed of her in those lonely nights in the dorm, Anton Ottenwalt (1789-1845). Marie took her time, however – unlike Ludovica and Siboni her heart was clearly not on fire. Perhaps she was still enjoying male attention too much. Who knows? Lawyer and civil-servant Ottenwalt, 29, finally got the now 24 year-old Marie to the altar in 1819, after everyone else had given up. Franz Schober turned his attention elsewhere, 'letting go' once more. He left Kremsmünster in mid-1815 in order to continue his studies at the University of Vienna. No more Kremsmünster, no more being interrogated by priests about a bit of harmless Selbstbefleckung.

The butterfly emerges

1815 was the year of the Congress of Vienna, which settled the post-Napoleonic order in Europe. The event bankrupted the Empire, but it was fun while it lasted. Vienna was full of the important and the not-so-important people from all over Europe, their lackeys and camp-followers. There were receptions, balls, parties and soirées. The city filled up with the entire gamut of human life, from emperors and kings down to prostitutes and chancers.

Why does this matter? Well, amid the tangled skein of the biographical accounts of Schober we are told long after the fact that the 19 year-old Schober was in his element: his older brother Axel was now a 'handsome cavalry officer' in the retinue of King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia and was able to arrange access to many events for him – at least, that is what Schober told someone decades later.

But like all of Schober's tales it has a biographical function: Schober, always mixing with important people at the centre of things, at graceful ease with and accepted by the highest members of the courts of Europe. Schober's memory appears to be gilding the lily, since Friedrich Wilhelm was in Vienna from 25 September 1814 to 26 March 1815, a time when the young Schober was still, at least nominally, a pupil in Kremsmünster. His participation in the Congress would have had to be a holiday activity at best. Who knows? Just one more knot to untangle.

Schober was granted a six year stipendium to study at the University of Vienna through the good offices of his mother's friend, Bishop Dankesreither. Schober signed up for Philosophy, then transferred to Jurisprudence and then thought about doing Medicine. It all came to nothing. We have no official withdrawal for Schober from the University – he just stopped turning up. His immatriculation was formally cancelled by the University in September 1819. As in the Kremsmünster school, serious studying and the drudgery of learning were just not his thing.

His father, Franz Xaver Schober, mouldered on silently in his Swedish grave, untroubled (we hope) by the fact that the 600,000 Gulden in silver that he had left to his widow Katharina was soon reduced to a fifth of that value: the final period of the Napoleonic Wars was a financially disastrous time for Austria and its citizens. Only eight years after Franz Xaver's death Torup castle had become a run-down dump. It came into the possession of the Stiernblad and Coyet families in 1812.

He would also, we hope, know nothing of lonely Catholic bishops, Italian tenors and amorous foreign noblemen, nothing of secret police, nothing of poor, sex-mad, dead Ludovica and nothing about little Sophie. Nor would he know anything of his charming bow-legged son Franz Adolf, fluttering from woman to woman and scheme to scheme. At least his son would be the soulmate of a genius for a while and so at least lift his father the small step from oblivion to being a footnote in a biography of someone he never knew.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!