Too much understanding

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-03-18 16:11

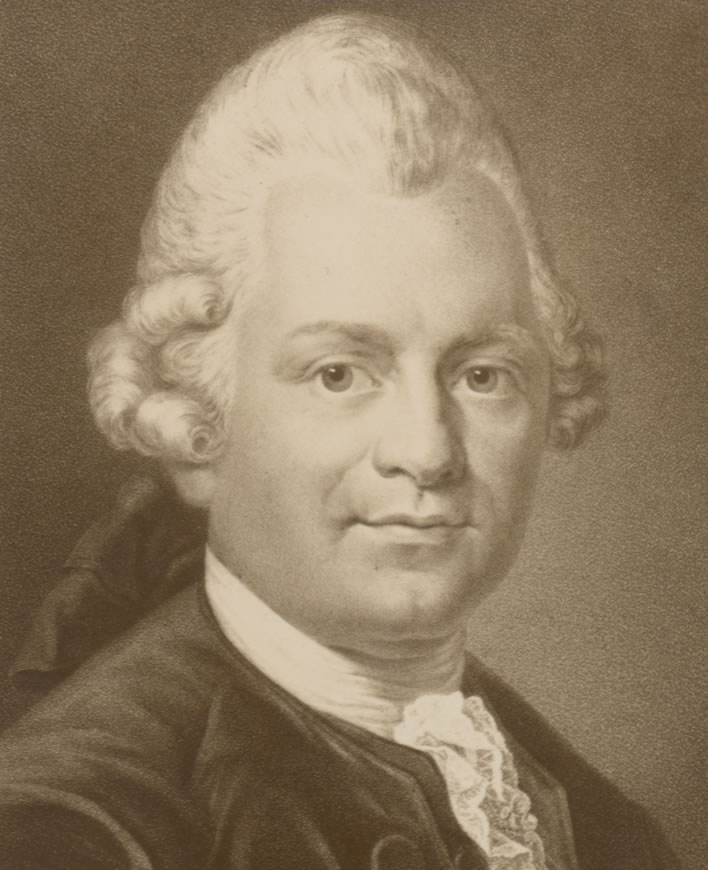

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) was one of the great writers of the Enlightenment in Germany. We discussed his most famous work, the play Nathan der Weise in January last year.

He was devoted to his wife Eva (1736-1778) – they were soulmates and finally married in 1776 after a long friendship. Lessing's joy was complete when she became pregnant with their son Traugott. His religious opponents – and he had many – frequently accused him of atheism, but the name he gave to his precious boy, 'Trustgod', refutes that charge completely.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Image 1878: Shakespeare Album / Library of Birmingham.

Little Traugott was born on Christmas Eve, 1777, but died the following day.

At the end of December 1777,[1] Lessing replied to a letter of condolence (now lost) that his friend Johann Joachim Eschenburg (1743-1820), the great Shakespeare translator, had sent him.

I seize the opportunity, since my wife is lain senseless, to write and thank you for your gracious sympathies.

My joy was only too brief. And I lost him so unwillingly, this son! Because he had so much understanding! so much understanding! — Do not imagine that the few hours of my fatherhood have turned me into such a demented fool of a father! I know what I am saying. — Was it not understanding, that he had to be dragged with iron forceps into this world having so quickly noticed so much folly here? — Was it not understanding that caused him to seize the first opportunity to flee? —And the little hothead is even taking the mother with him!— For there is little hope that I will be able to keep her. —I just wanted things to be good, just like other people. But it has gone badly for me.[2]

Strong men read this and turn pale, gentler natures well up.

The German writer and satirist Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), for whom Lessing was a great hero, read it and commented on Lessing's gräßlich witzigen Worte, his 'appallingy clever words'. Read it again – you will see what Heine means. Satire of the highest order, almost beyond the term 'satire' – perhaps we don't even have a category for such writing – which Heine, that other great German satirist, recognized immediately.

Heine wrote of Lessing:

There was a misfortune over which Lessing never expressed himself openly to his friends: this was his terrible loneliness, his intellectual isolation. Some of his contemporaries loved him, no one understood him.[3]

Ten days after the loss of his son Traugott, his beloved wife – his soulmate – died of childbed fever. He wrote once again to Eschenburg, but all cleverness had left him:

My wife is dead; and this experience I have now also endured. I am happy that many more such experiences cannot be left over to be endured; and I am quite relieved.

References

- ^ In some collections of Lessing's letters the date of this letter is given as 3 January 1778. This date is written in Eschenburg's hand, however and is presumably the date he responded. The most likely dating is 31 December 1777.

-

^

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Werke und Briefe in zwölf Bänden. Hrsg. von Wilfried Barner. Briefe von und an Lessing. Frankfurt am Main 1987, 1988, 1994. Brief vom 31.12.1777, 11/3, 18.

Ich ergreife den Augenblick, da meine Frau ganz ohne Besonnenheit liegt, um Ihnen für Ihren gütigen Antheil zu danken. Meine Freude war nur kurz. Und ich verlor ihn so ungern, diesen Sohn! Denn er hatte so viel Verstand! So viel Verstand! — Glauben Sie nicht, daß die wenigen Stunden meiner Vaterschaft mich schon zu so einem Affen von Vater gemacht haben! Ich weiß, was ich sage. — War es nicht Verstand, daß man ihn mit eisernen Zangen auf die Welt ziehen mußte? daß er so bald Unrath merkte? War es nicht Verstand, daß er die erste Gelegenheit ergriff, sich wieder davon zu machen? — Freilich zerrt mir der kleine Ruschelkopf auch die Mutter mit fort! — Denn noch ist wenig Hoffnung, daß ich sie behalten werde. —Ich wollte es auch einmal so gut haben, wie andre Menschen. Aber es ist mir schlecht bekommen. -

^

Heine, Heinrich, and Jürgen Ferner. Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Reclam, 1997, Universal-Bibliothek 2254, p.87.

Ein Unglück gab es, worüber sich Lessing nie gegen seine Freunde ausgesprochen: dieses war seine schaurige Einsamkeit, sein geistiges Alleinstehn. Einige seiner Zeitgenossen liebten ihn, keiner verstand ihn.

Heine was mistaken – Lessing did express it in letters to those closest to him, but we have had enough misery for one article.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!