Cooling down the hotheads

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-04-24 16:45

Aloys Fischer's farewell

That trigger came on 20 February 1820, nearly a year after Kotzebue's murder, in the form of a farewell party for Aloys Fischer, a second-year law student at the University of Vienna.

Fischer's stepfather had just died and his mother wanted him back in Landeck, in the Tyrol, to help arrange his affairs. On 20 February, the evening before his departure, his friends arranged a farewell party for him in a private room at an inn, bey der Schwane, on the Landstraße in Vienna. According to [Klein 193:5, following Pichler] the student get-togethers that culminated in Fischer's farewell party were a recurring event designed to allow discussion of literature, philosophy and politics – just those things that Emperor Franz didn't want his subjects to discuss. Look what had happened in France when they did that.

Fisher's account of the ejection of a mysterious stranger from the meeting has passed into legend as the moment when a 'spy' was discovered and thrown out:

Among the familiar faces of the young people there was a stranger. Fischer went up to him and, using the relaxed 'du' form, the standard form of address among students, asked Wie heißt du?. The stranger replied curtly: Ich bin mit Ihnen nicht du, 'I am not on du terms with you', requiring the formally polite Sie form used with strangers. Fischer told him calmly that this was a private party and asked him to go to another room. The stranger answered rudely once more, after which a lawyer friend standing behind Fischer grabbed the man by the collar and manhandled him roughly to the door.

[Helfert 14]

We are left thinking that, if this was a spy, he wasn't a very good one.

Spy or no spy, the police struck early the next day. In the weeks following that gathering, depending on whom you believe, between 140 and several hundred students who were implicated in conspiratorial clubs and/or with connections to German Burschenschaften were rounded up and arrested. We are told that Senn was not at Fischer's party and so missed the first police fishing expedition.

Fischer gets away

Through good luck and some quick thinking Fischer himself avoided arrest. It's a tale worth telling.

The farewell meeting went on until four o'clock in the morning. Fischer left and took a carriage to Salzburg. At the city gate his passport was taken from him and he was told to collect it from the police station. It was past lunchtime when Fischer reported to the police. He was lucky: there was only one policeman on duty and he seemed to be sympathetic to Fischer. He didn't return his passport but simply said to him: 'Get yourself gone, there is a wanted notice out on you'. Fischer left the police station, hired a horse and carriage and instructed the driver to get him into Bavaria without anyone noticing. Down the ages it has been so: there is nothing a taxi-driver likes so much to drive away the boredom than being paid to avoid the police.

The route from Salzburg to the Tyrol passes across a small peninsula of Bavarian territory. Around midnight they arrived at the border crossing. An elderly customs officer came out of the hut and asked to see his passport. While Fischer was fiddling in his pockets the coachman asked the customs officer to raise the barrier, which was spooking his horse. As soon as the barrier was up the coachman gave the horse the whip – coach and Fischer raced off, 'throwing gravel and sparks into the night'.

The rest of the journey passed without incident. They skirted round Innsbruck through the suburbs on the northern side. He stayed overnight at an inn and then caught the next express coach along the upper Inn valley until he got home to his mother in Landeck. The whole journey had been well over 500 km.

The local authorities gave Fischer an arrest confining him to Landeck, but he ignored that, went to Innsbruck and signed up to continue his studies at the University.

There was some contact with the Police Director in Innsbruck, Alois Kübeck, but then the whole affair seemed to die down, whether through good luck, Tyrolean solidarity against the Viennese or just incompetence – who knows? Perhaps all three.

Rounding up the academics

As we have already noted, in the weeks following Fischer's farewell party a large number of students who were implicated in conspiratorial clubs and/or with connections to German Burschenschaften were rounded up and arrested.

Worrying for the authorities was that among those interviewed and arrested were students from all faculties, even including medicine. There had been 20 medical students at Fischer's farewell party, for example. Up to now the police had concentrated on the 'dreamers', the students of philosophy. On 3 March an order was issued to extend the monitoring of students to all faculties. Such extensive snooping cost money: the willingness of the police to spend it shows how seriously they took the threat from academia.

Most importantly they acquired a nark, a student who, for a promise of money and anonymity, was prepared to observe and carry report on his fellows, their clubs, what they wrote and did. By 12 March his first report was delivered. It resulted from a contact with a German first-year philosophy student called Heinemann. The snooper's demand for a pay rise because of the risks he was running was met on 25 March. He received 100 Gulden (CM), which, for the purposes of comparison, is about what (we think) Schubert earned for giving the Esterházy family 50 hours of music lessons in Vienna.

The police picked up Heinemann and extracted with threats and presumably beatings a list of 55 names, most of them third-year philosophy students but also lawyers and doctors. Among the names of the six main suspects on the list was that of Johann Senn and a law student, a certain Scheiger.

When they raided Scheiger's apartment they found evidence linking him to student activism in Germany as well as a kind of diary in which he – foolish boy – had committed all his subversive thoughts to paper. Senn's name was in there, together with a rather twisted view of Sand's murder of Kotzebue and some musing about the end justifying the means. One example:

24th Monday: the truly great sacrifice is given by those who are able to lose even that which the world calls honour in pursuit of a holy purpose. That's why I admire Sand so much, because he is not afraid of being called by the masses a common murderer. I had an interesting talk to Senn yesterday. Among other things I came to the conclusion that no decision can be made between whether the patience the Germans show while they get hammered is magnificent true patience or just incapacity. Can the sentence 'the end justifies the means' be shown to be true?

[Otto 888]

The residences of the other suspects were given a 'Visitation' simultaneously, including Senn's on 24[?] March 1820.

Senn's arrest

Senn did not go quietly, but caused the police to note his 'exalted rebelliousness'. The friends who were present gave him noisy support, among them Franz Schubert, who 'verbally assaulted' the police officers.

The police officer commanding reported on 27 March 1820 as follows:

Report of Police Chief Inspector von Ferstl on the disobedient and insulting behaviour displayed by Johann Senn, born in Pfunds in the Tyrol, complicit in a student society, during the document inspection and confiscation of his papers in his apartment, during which he used among others the expression 'he didn't need to worry about the police' because the government was too stupid to be able to penetrate his secrets. Furthermore the friends of his who were present, the assistant teacher from the Rossau, Schubert, and the law student Steinsberg [recte Streinsberg], as well as the students who later arrived, the private student Zechenter from Cilly and the fourth-year law student son of the businessman Bruchmann, used the same tone and attacked the officer with verbal abuse and invective.

[Enzinger Bruchmann 285]

Those who like to think of Franz Schubert as the cuddly little composer of the Biedermeir, that imaginary period of frocks, furniture, salons and dancing, should perhaps pause here for a moment to consider the scene: the 23 year-old Schubert is hanging out with a group of political subversives and hurling abuse at the police. We do know that Schubert had a short fuse and here we see it in action. On this occasion he got away with it – just:

In respect [of the verbal abuse] Chief Inspector von Ferstl has issued a summons, so that this excessive and criminal behaviour should be appropriately investigated. […] Furthermore, those individuals who during the 'visitation' of Senn behaved badly towards Chief Inspector von Ferstl will be summoned to appear and will be threatened with a stern warning. Court Secretary Steinsberg [recte Streinsberg] and Businessman Bruchmann will be informed of the behaviour of their respective sons.

Ibid 286

Streinsberg and Bruchmann were from important families, hence the care of the authorities for their familial welfare. In the feudal Austrian Empire the Schuberts, father and son, were nobodies and thus not worth the trouble. When asked what his profession was, Schubert told the police he was a Teaching Assistant (=nonentity) in his father's school in Rossau, a post which he had in practice given up some years before. Had he told the police the truth, that he was a freelance musician, he might well have been imprisoned as a vagrant.

It was indeed a good thing that Schubert was no longer a teacher, since after this official warning about his behaviour and his association with political desperados there was now a police file on him in the Empire of Paperwork. He would have no chance of a job in an educational system run by a combination of the Catholic Church and state bureaucrats that demanded 'impeccable public conduct' as a condition of employment. For Franz I, it was bad enough that he had professorial hotheads in the universities without having them teaching impressionable children in the schools.

Senn's interrogation

Count von Sedlnitzky (1778-1855), the Chief of Police, set out the goals for the interrogation of Johann Senn in an order to the Director of Police in Vienna on 25 March 1820. The report of the interrogation should be comprehensive and contain 'details of his life so far, his private and personal relationships, his mental character and his moral and political thoughts and actions'.

Senn was interrogated on 28 March. It was going to be a long haul before Sedlnitzky's goals were reached:

In the this connection Senn appeared as one of the most passionate and dangerous zealots, so much so that one attempted to have him declared insane. However, in the opinion of the medical officer Dr von Borschenschlag, Senn had suffered mental confusion and was in a state of mental overload, the cause for which lay in the excited plebian mood of the times and in the pernicious ideas of revolution and dogmatism that emanate for the north German universities.

Bidden to answer the first summary interrogation questions, Senn replied that he was so offended by the search through his papers and the subsequent arrest, that he would give no answer at all until he was compensated for the incident. The state administration did not have the right to carry out a search of the premises of an innocent person, let alone arrest him.

Only after much alternately serious and mild persuasion by the interrogator did Senn answer: I would answer you, since I see with whom I am dealing, but my principles do not permit it. 'I was indeed born in the Austrian state, but that was not something I chose. Since I have now come of age I shall argue with the administration of the state; I do not view myself any more as a subject of any state, rather as my own man. I therefore wish to declare to the power of the state, under what conditions I will stay here; if they don't agree to these conditions, then I shall leave.'

After the interrogators debated with Senn the excentricity and monstrous nature of his principles and tried to persuade him otherwise he was threatened with bread and water starvation and finally corporal punishment, which were immediately carried out. This made him more malleable and he answered the questions that had been originally put to him in the first attempted summary interview, that he was 24 years old, born in Pfunds in the Tyrol and had lived in Vienna since 1807.

[Otto 889]

When Sedlnitzky read the report of the interrogation on 28 March 1820 he noted that it 'gave evidence of his questionable principles and an excentric zealotry of the most dangerous type'.

He grasped the situation that faced him and summarised it perfectly, albeit in a looking-glass or anti-matter version of the one we would use today:

Although the meetings held here in themselves do not appear to have reached any great degree of political danger, the signs are visible that out of them, clubs that consist of a few hot and fantasist heads are starting to develop in which the ideas of German culture, the freedom of the people, national representation and other excentric ideas may be discussed and exchanged.

Ibid 891

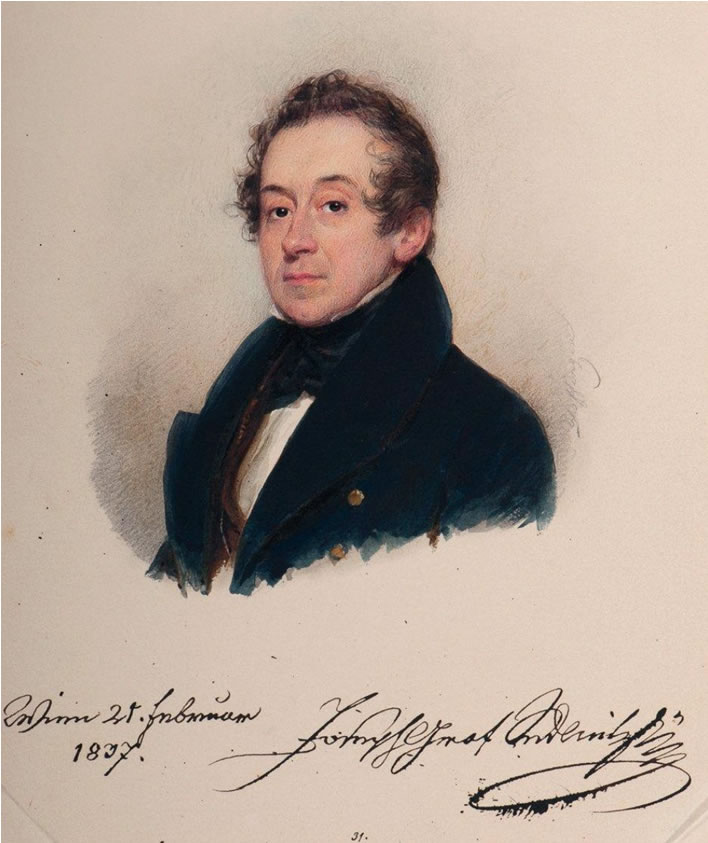

Moritz Michael Daffinger (1790-1849), Graf Joseph Sedlnitzky, 1837. Image: Beaussant-Lefevre, Paris

For Sedlnitzky, writing in 1820, all the great seed passions that would preoccupy the following generations and that were now starting to germinate – German nationalism, freedom, democracy – were merely 'excentric ideas'. The first would flower 50 years later, the other two would require well over a century, during which period the lawnmower of history would be run over them several times.

Senn's imprisonment

Senn stayed in police prison for one year two months and ten days.

Some accounts, intent on emphasising the heartlessness of 'Metternich's System', say that after the first interrogation he was simply forgotten or ignored by the authorities. Those who have any knowledge of the Empire of Paperwork know that it never forgot.

It seems more likely that Senn's interrogation was continued throughout much of the period of his detention in order to extract every tiny detail from him and, of course, break his spirited resistance. Torturing someone with starvation takes its time: a few days or even a week or two are not long enough. Senn would have been 'worked on' during that period with hunger and cold. He spent the winter of 1820/21 in a police prison.

There would be beatings with a cane that were conditional on his cooperation and progress. The police were permitted to use both of these measures more or less according to taste.

We find hints of the technique in the report of the initial interrogation, where we read of the use of 'alternately serious and mild persuasion by the interrogator'. It seems that the 'good-cop/bad-cop' procedure is not a recent invention.

We can be sure that Senn's interrogation was painstakingly methodical and consequently took time, in accordance with the goals set out by Sedlnitzky in his order to the Viennese police. We can compare it to the interrogations carried out 25 years previously on members of the Jacobin Conspiracy, where the subjects were made to write an account of their lives and beliefs. In Senn's case his interrogators would be particularly interested to hear all his ideas, how and where he had formed them and who had influenced him. They would certainly want to find out the names of the people with whom he had discussed those ideas.

Writing in 1873, Hyacinth Holland tells us that Senn, driven by hunger, 'dictated 92 pages – his entire philosophical-political creed' [Holland 10f]. Although almost everything he writes about Senn is in error in one way or another, Holland's acknowledgement of the existence of such a document has probably some basis in reality. However, Senn, as in all other police interrogations we know about, would have been given a stack of paper and a pen and told to get on with it if he wanted to eat that day. The thought that Senn was 'dictating' his Hegelian ramblings to a Viennese copper is amusing, but a thought too far.

Some scattered excerpts from Senn's autobiography surface in the scattered accounts of the event, but I have not been able to find the full document in original or transcript.

Senn forgotten? No! – we have only to consider the continuing interest the police took in him after his release and deportation, fuelled by Sedlnitzky's particular and unremitting animus towards him. Senn was certainly not someone who had been forgotten for a year. After the interrogation was complete Senn's case file would be passed around the upper echelons of the bureaucracy waiting for someone to take a decision on what to do with this troublemaker. There can be no doubt that final decision had to be approved by Franz I himself.

[Klein 194:3] puts forward the theory that the results and recommendations from the police interrogation sat on Franz I's desk for months on end, a suggestion that is scarcely credible given what we know about Franz's extreme devotion to detail and paperwork. Franz did not have a pending tray on his desk and never seems to have left issues lying around unresolved. It was just not in his obsessive-compulsive nature.

Klein goes on to tell us that Senn was finally released when the City Medical Officer produced a report on the dangers to the health of the arrestee from continued lack of light and fresh air. This sounds plausible: even in Franz's empire the authorities could not just leave someone to rot in jail without any judicial process.

Senn was never tried or convicted of anything – presumably the authorities didn't want a public martyr on their hands. Furthermore, the question of what he had done for which he might be tried would at best be a legal nicety. Even the police under Franz I could not successfully prosecute someone for belonging to a forbidden organization when most of the others who belonged to it had been allowed to get get away more or less without serious punishment.

We note too that nothing directly incriminating seems to have been found during the search of Senn's rooms. We might well assume that, alerted by the activity of the police in rounding up students and professors directly after Fischer's farewell party, Senn would have destroyed or hidden any incriminating material. Even under Franz's belljar, Senn could hardly have been prosecuted on the basis of what someone else had written about him.

The length of Senn's imprisonment during the investigation is probably an indication of the degree of resistance he put up. Whereas a sensible person cooperates, fakes remorse and is quickly set free, we see how Senn fought a mighty battle just over accepting the right of the police to question him, even to the point of refusing to give his name. When we think back to the accounts of his father's character we might come to the conclusion that pedantic stubborness was in the Senn DNA.

Camping it up

A small band of Schubert scholars got it into their heads some years ago that a number of the members of the Circles of Friends were bound together by homosexual feelings and not just shared biography, friendship or cultural interests. Despite the fact that the evidence produced for this did not stand examination, the idea that some members of the Circles were in homoerotic turmoil still seems attractive to some commentators for some reason. We therefore still have to waste pixels battling these fantasies.

Johann Senn was also dragged into this camp turmoil. [Dürhammer 202] for example, suggests that Senn's arrest may have been for homosexual behaviour rather than political activity in student clubs. He has to admit that, since many of the police files have been destroyed, there is no evidence for this at all. He further suggests that Senn's 14-month stay in the police prison was the length of sentence that someone convicted of homosexual activity would be given. Again no records exist. As far as we know, Senn remained in the police prison during this entire period – the prisons for penal punishments were quite different establishments and Senn would only be sent to one of those following a trial and formal sentence. A hundred or so pages later, in his entirely political treatment of Senn's arrest, [Dürhammer 313] ignores his own theory.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!