The French, dontcha luv 'em!

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-05-19 12:53

Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832) spent a tumultuous year and a half in Alsace, between April 1770 and the autumn of 1771. The 21-year-old studied Law at the University of Strasbourg; fell in love with, wooed, courted and then brutally dumped Friederike Brion, a vicar's daughter in Sessenheim; cured his vertigo in Strasbourg Minster and decided he did not like the French in general or their language in particular.

The two images we have of Goethe that are closest to his Strasbourg years.

Left: Goethe in 1778, eight years after leaving Strasbourg. The picture is a coloured copy by Prof. Eberhard Ege (1868-1932) of an original by Georg Oswald May (1738-1816) painted in 1779.

Right: Goethe with a silhouette, painted by Georg Melchior Kraus (1737-1806) in 1775-76, c. four years after leaving Strasbourg.

Images: Goethezeitportal.

In this latter decision he was part of the Zeitgeist among German writers in the second half of the 18th-century who were rejecting courtly French (and Italian) affectation and favouring German as part of a new German identity.

Left: presumed to be the 16-year-old Goethe, artist unknown. Image: Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Haus.

Right: Goethe by Johann Heinrich Lips (1758-1817), 1791, 20 years after leaving Strasbourg. Image: Goethezeitportal.

Those of us who, on long journeys across rural France, have stopped at a bar in need of refreshment – une bière et un pacquet de cochon qui gratte, s'il vous plait, garçon! – will fully relate to Goethe's description in his autobiography of his decision to reject French as an unattainable language goal that was really not worth the struggle:

I liked the French language from my youth onwards; I got to know it as a result of a busy life and got to know a busy life through French. It became almost a second mother-tongue, acquired without grammar or lessons but through use and practice. Now I wanted to use it with greater ease and therefore chose Strasbourg as my place of academic study. But it was there that I experienced the opposite of my hopes and I was turned away from rather than towards this language and these customs.

The French, who try hard to be polite, are considerate towards strangers who try to speak their language: they will never laugh at someone's mistakes or criticise them directly. They can, however, not bear such sins against their language and therefore restate what one has just said in a different formulation using the expression that one should have used, thus leading in this way to the understanding of that which is correct and fitting.

Even though, if one is serious enough and has enough self-deprecation to act the pupil, one in this way gains and is improved, however, one still feels to some extent humiliated. Since one is speaking about the subject but is all too often interrupted or distracted one lets the subject drop impatiently. This affected me more than others, in that I believed that I had something interesting to say and wished to hear interesting things and did not want to be repeatedly brought back to the form of the expression; something that happened to me frequently because my French was more motley than that of many other strangers. I had noted the expressions and accentuation in footmen, valets, guards, young and old actors, theatre lovers, peasants and heroes […]

Perhaps we would have resigned ourselves to this, had not an evil genius whispered in our ears that all attempts by a foreigner to speak French would always remain unsuccessful. A trained ear will always detect the German, Italian, or Englishman under a French mask – one will be tolerated but never received into the lap of the one true language church.

Instead of accepting this, as green wood has to accept what the dried wood has predetermined, we became annoyed at these pedantic injustices. […]

We came to the opposite conclusion, that we should reject French completely and instead dedicate ourselves with force and decisiveness to our mother tongue. […]

[In Strasbourg] at our table we spoke nothing but German. […] Even when someone was there who preferred French speech and customs, as long as they were with us they subsumed themselves to the general tone.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, and Walter Hettche. Aus meinem Leben. Dichtung und Wahrheit, 'From my Life. Invention and Truth' (c. 1811–1833). Durchges. und bibliogr. erg. Ausg. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2012, 3. Teil, Eilftes Buch, p. 514-7. Translation ©FoS.

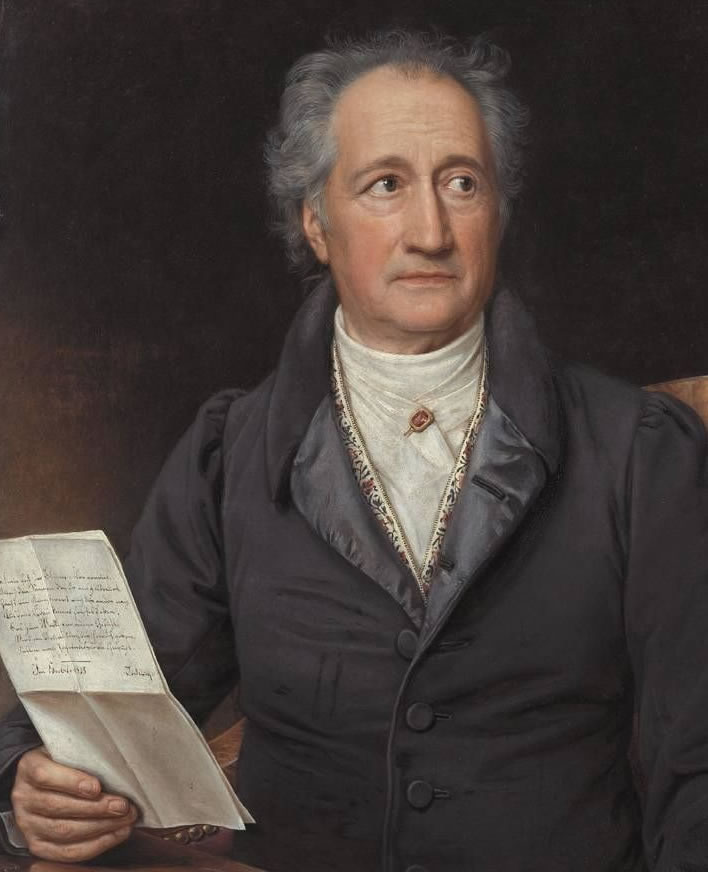

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1828 (c. 79 years old). Shown holding a French letter and puzzling at its meaning. Image: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!