4 December: Saint Barbara's Day

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-12-05 17:07 Updated on UTC 2017-12-13

Finding Barbara

No one knows where and when Saint Barbara was born or where and when she died. She has no demonstrable historical existence. None whatsoever.

The inconsistent tales about the Barbara figure in the hagiographies are full of wonders that are completely incredible to the rational mind; the inconsistent details of her extremely bloody martyrdom are also told and embellished in loving detail. There is as much historical authenticity in these tales as there is in the Grimms' 'Rumpelstiltskin'. At least we know who wrote that.

Once the legend of Barbara gained a foothold in the seventh century, four centuries after her ascribed lifetime, her popularity grew in the east and the west over the next two centuries. Her legend grew in the retelling. The core of her story is as follows:

She was the only daughter of the pagan Dioscorus. To shield her beauty from the eyes of men and to preserve her from evil, her father built a tower where she lived shut away from the world. She became a Christian. Many men unsuccessfully sought her hand in marriage but she rejected them all.

Dioscorus, about to set off on a journey, ordered the construction of a magnificant bathhouse for his daughter. On his return, he learned that she had destroyed his idols and changed the plans from two to three windows in order to symbolize the Holy Trinity. She told him that she had become a Christian. He drew his sword to kill her. The floor broke away beneath her and carried her to a mountain peak where two shepherds were watching their flocks.

Dioscorus pursued his daughter and learned of her whereabouts from the second shepherd. The shepherd was punished for his treachery against Barbara by being turned to stone and his sheep into locusts. Dioscurus seized Barbara and dragged her back to the city. He handed her over to the Prefect Martianus. She was tortured to make her recant.

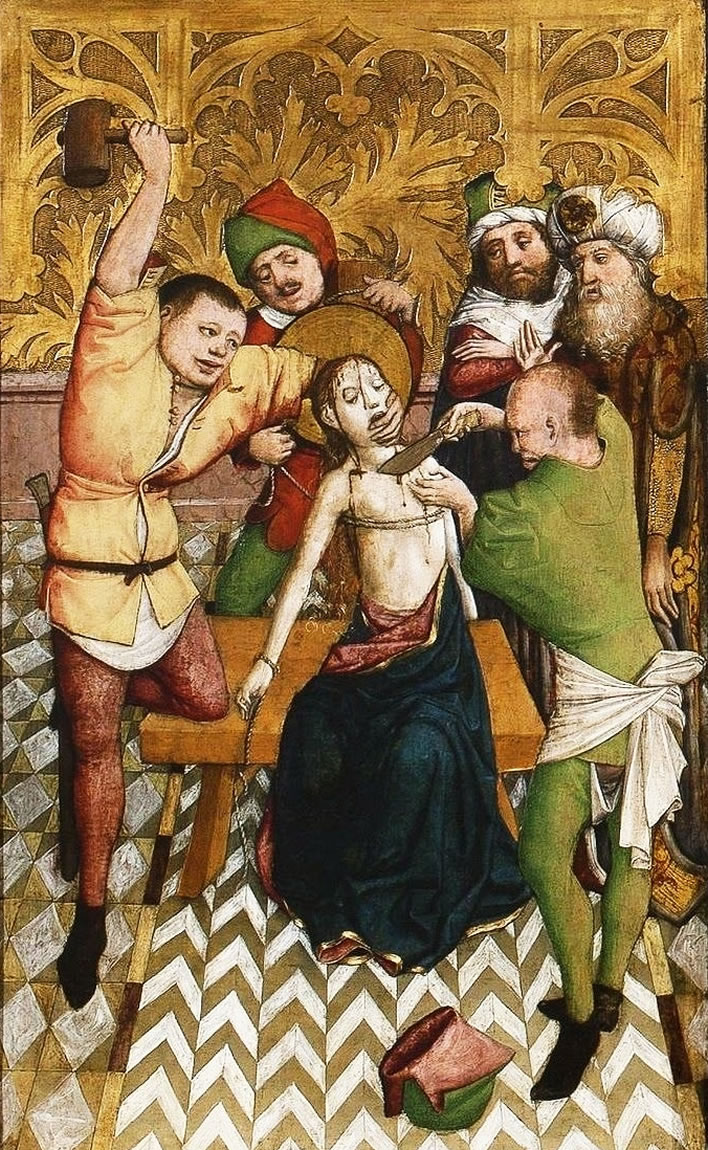

At night the Lord appeared, comforted her, and healed her wounds. The next day she endured more suffering: her sides were torn open, her wounds lacerated, her head battered, and her breasts cut off. She was dragged or paraded naked through the streets. Finally she was decapitated by her own father. As a punishment, fire fell from from heaven and consumed him utterly. A certain Christian called Valentine buried the saint. Many miracles took place at her tomb.

The core narrative is derived from Williams, Harry F. 'Old French Lives of Saint Barbara' in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 119, No. 2 (Apr. 16, 1975), pp. 156-185. Online (access restrictions).

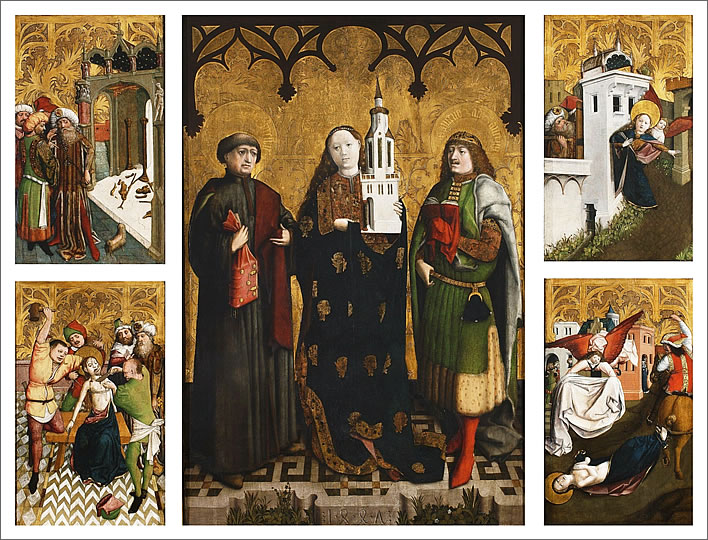

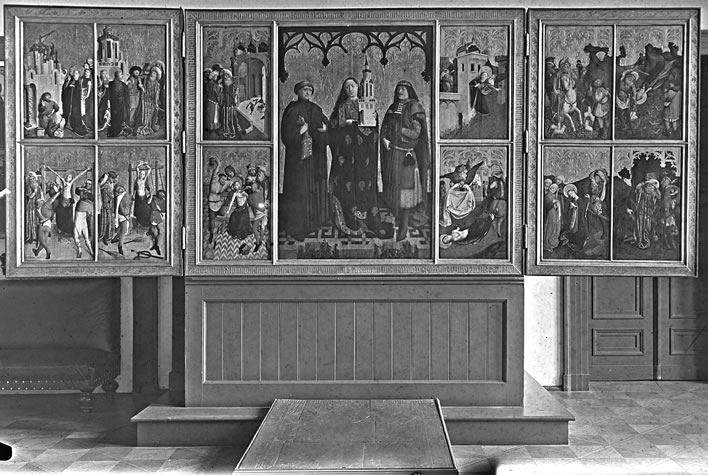

The magnificent Altarpiece of Saint Barbara, 1447, by the Master of Saint Barbara’s Altarpiece, done for the altar of St Barbara’s Church in Wrocław. This is the central panel – the wings were lost during World War II.

Top left: Dioscorus looking at the shattered remains of idols in the pagan temple; bottom left: the torturing of Barbara; centre: Saint Barbara with Saints Felix and Adauctus; top right: Barbara carried from the tower by an angel; bottom right: Barbara being dragged naked through the streets.

Image: National Museum in Warsaw. [Click to open a large image in a new browser tab.]

Much ado about nothing

The rationalist's problem with the various accounts of Barbara's life is that they are simply so overloaded with the mysterious and the miraculous that there is no plausible historical centre. There is no part of her biography that makes sense at all. Once all the implausible elements are taken away, nothing is left behind.

The implausible elements are laden with symbolism and religious moral lessons. Immediate justice is dispensed on earth: the treacherous shepherd is fossilised on the spot – though we are left wondering what the sheep did wrong that they should be turned to locusts; angry dad Dioscorus is vaporised with a bolt of lightning – but only after he had beheaded his daughter; overnight succour is given to Barbara herself, making her fit enough to endure the following day of torture. So many things to ponder, so little time to ponder them!

The Barbara legend emits all the odours of an early Christian foretime that has not yet developed the Dantescan encyclopedia of just punishment post mortem in Hell. It shares many characteristics with the Old Testament and even with the gods of Ovid's Metamorphoses, in both of which the respective gods do not hang around when justice or retribution needs to be dispensed.

Dr Freud and modern feminists would have much to say about Barbara's sufferings, particularly about the nature of the tortures to which Barbara was subjected. We also note that some incidents of her biography roughly follow the template established by the martyrdom of Jesus: betrayal, intervention of the political authorities, torture, humiliation and execution.

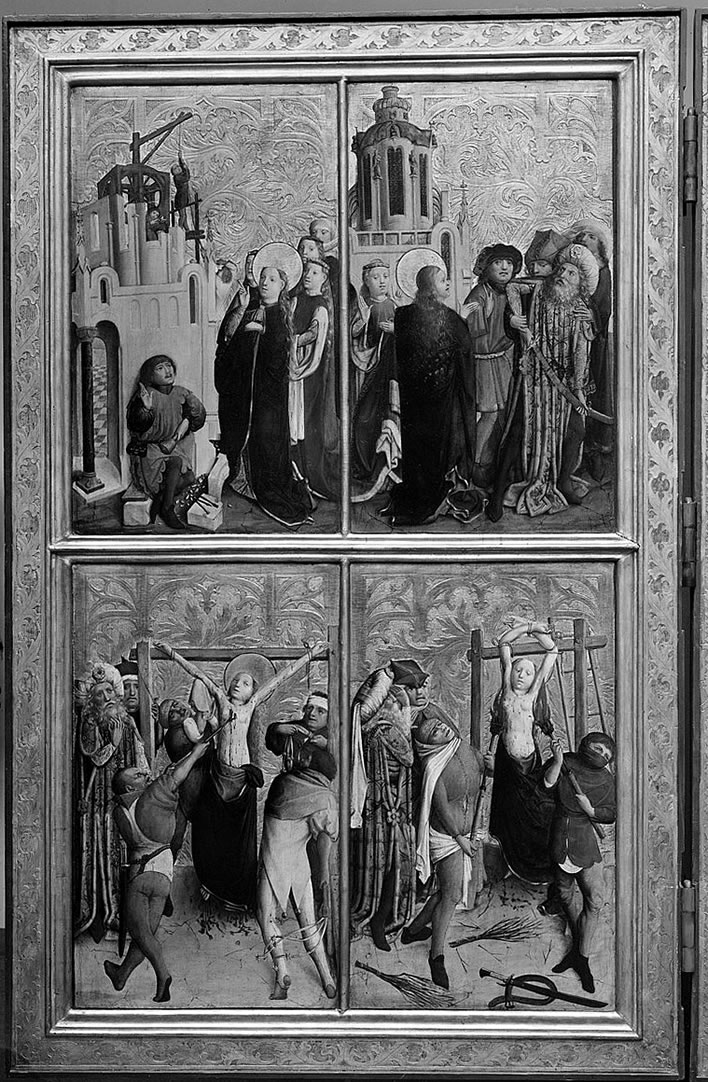

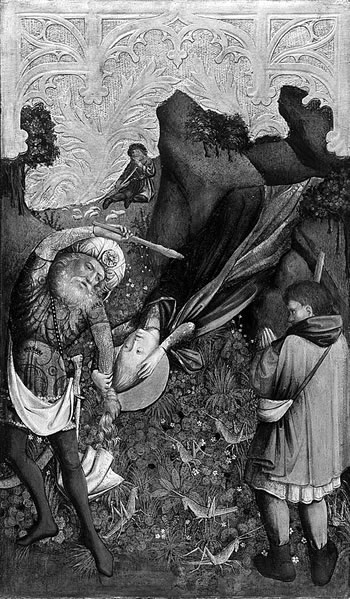

The torture scene from the Altarpiece of Saint Barbara, 1447. Barbara's father, Dioscorus (right) and Martianus the Prefect (left) are at the right rear, watching the action. Lots of interesting details here for the ghoulish.

The date of her martyrdom was set as 4 December and the year 267 or 306 or… whenever. These specifics first pop up about a thousand years after that moment itself and have to be considered to be complete fantasy. By the time her story appears in a 15th century French chronicle she is credited with performing 13 miracles.

Hearts and bones

There are relics in existence that are claimed to be bits of her, the most complete of these being currently in St. Vladimir's Cathedral in Kiev. The legend of the journey of her remains from wherever she died to Constantinople, thence to Kiev is as incredible as her life story.

Valentinus presumably buried her sometime in the third century AD somewhere, but she turns up in St Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in Kiev. A story is concocted around her transport there, but the story and the relic to which it was attached have no credibility. It is a legend upon a legend.

The relic legend describes some complicated journey in the company of a living Barbara from Constantinople to Kiev. How the relics got to Constantinople no one knows. Others have the relic travelling from Constantinople to Venice, the same route taken by the books that started the Italian renaissance.

The first records we have of her relic in Kiev are the accounts of visitors from the end of the 16th century who tell of being shown a corpse in St Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery. [Thanks to Nicholas Zharkikh for elucidating these records.]

The first account we know of is that of Laurentius Müller. We know little about him– not even his dates – but he left a memoir of his travels that was published in Frankfurt am Main in 1585. In this memoir he tells of a visit to St Michael's Monastery in 1581 where he viewed the remains of Saint Barbara:

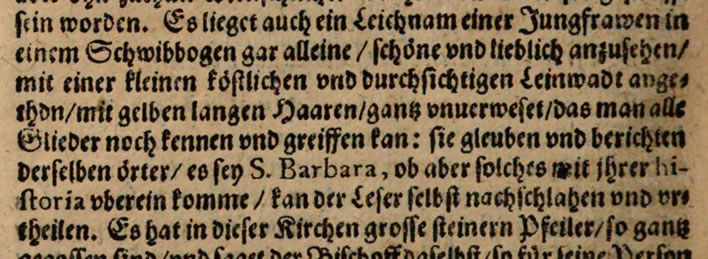

The body of a young woman rests in an archway all on its own / looking beautiful and gentle / covered with a small, delicate and transparent linen sheet / with long yellow hair / without any decomposition / so that one can see and grasp all the limbs: they believe and report in these parts / that it is Saint Barbara, but whether suchlike agrees with her story / the reader can research and judge for themselves.

Es lieget auch ein Leichnam einer Jungfrawen in einem Schwibbogen gar alleine / schön und lieblich anzusehen / mit einer kleinen köstlichen und durchsichtigen Leinwadt angethan / mit gelben langen Haaren / ganz unverweset / das man alle Glieder noch kennen und greifen kann: sie gleuben und berichten derselben örter / es sey S. Barbara, ob aber solches mit ihrer historia übereinkomme / kann der Leser selbst nachschlagen und urtheilen.

Curaeus, Joachim: Polnische, Liffländische, Moschowiterische, Schwedische vnd andere Historien, so sich vnter diesem jetzigen König zu Polen zugetragen Schlesische General Chronica , Leipzig 1585. Online.

The veracity of Müller's account is underscored by the testimony of another visitor to St Michael's Monastery in 1594, thirteen years after Müller, the German diplomat Erich Lassota von Steblau (1550?-1616):

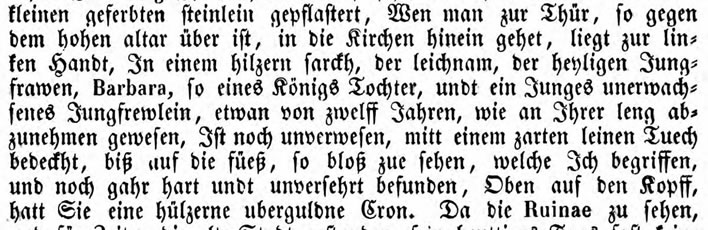

When you enter the building, with the high altar facing you, on your left there is a wooden coffin containing the body of the blessed virgin Barbara, a king's daughter and a young immature girl, about twelve years old judging from her height. She is not decomposed, covered with a delicate linen cloth that stretches down almost to her feet, which I felt, finding them still hard and intact. On her head was a gilded wooden crown.

Wen man zur Thür, so gegen dem hohen alter über ist, in die Kirchen hinein gehet, liegt zur linken Handt, In einem hilzern sarckh, der leichnam, der heyligen Jungfrawen, Barbara, so eines Königs Tochter, undt ein Junges unerwachsenes Jungfrewlein, etwan von zwelff Jahren, wie an Ihrer leng abzunehmen gewesen, Ist noch unverwesen, mitt einem zarten leinen Tuech bedeckht, biß auf die füeß, so bloß zue sehen, welche Ich begriffen und noch gahr hart undt unversehrt befunden, Oben auf den Kopff, hatt Sie eine hülzerne uberguldne Cron.

Lassota von Steblau, Erich. Tagebuch des Erich Lassota von Steblau : Nach einer Handschrift der von Gersdorff-Weicha'schen Bibliothek zu Bautzen herausgegeben und mit Einleitung und Bemerkungen begleitet von Reinhold Schottin . Verlag Barthel, Halle, 1866. Online.

Both eyewitnesses observed and touched the body of a young girl, completely intact – head and all – in a remarkable state of preservation. If this is Saint Barbara she was not beheaded. Neither Müller nor Lassota explicitly mention a missing head. Lassota talks of a crown, the presence of which implies strongly that it is resting on a head. Müller expresses a delicate and diplomatic scepticism, leaving his reader to judge 'whether suchlike agrees with her story', which must be an oblique reference to the surprising presence of a head.

Both men were taking hurried notes, a fact which reinforces the veracity of their observations. Careless talk on religious or political matters could easily cost you your life at that time, so writers became adept at veiling such utterances, even when writing in haste. Müller's careful phrasing of his scepticism is an excellent example of this self-censorship in action.

In addition, the perfect state of preservation of the corpse is not compatible with 1,400 years of decomposition and transportation. Even saints rot. As Barbara's cult developed the body is transferred from wooden boxes to richly decorated caskets.

At some time the head that was reported by Müller and Lassota seems to have disappeared, possibly going missing in all the boxing and reboxing that went on: stolen, sold, lost or removed to fit the saint's story – who knows? The left hand seems to have had its own history, too.

In 1935, during the communist destruction of religious monuments, St Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery was vandalised and left in ruins, its riches stolen and sold. Barbara's relics were moved around, ending up in St Vladimir's Cathedral in Kiev, where they rest to this day.

The shrine with the relics of Saint Barbara in St Vladimir's Cathedral in Kiev. According to the inscription on the pediment, she was martyred in 306, hence 2006 was the 1,700th anniversary of her death. Image: doxologia.ro. Somehow we have progressed from the girl in the box seen by Müller and Lassota in the late 16th century to this.

The adoration of St Barbara in the Catholic and Orthodox states of eastern Europe is strong to this day, despite the historical turmoil in these countries down the centuries. In 1870 100,000 pilgrims visited St Michael's monastery. In 2006, for the celebration of the 1,700th anniversary of her death, the Kiev relics were taken on a tour of Ukraine, accompanied by large crowds.

Top left: Another view of St Barbara's shrine in St Vladimir's Cathedral in Kiev. The remaining photos were taken on her Ukrainian tour in 2006. Images: Dmytro Redchuk.

The Monastery of Mega Spileo in Kalavryta, Greece, claims to have her skull, which they keep in a golden pot with a peephole in a glass cabinet. I have no idea of its provenance: there comes a point when one simply stops asking.

A skull in a gilded pot in a display case. The peephole is open at the top. It is labelled in Greek as the 'Head of Saint Barbara' – so that's what it must be. Image: Oana Nechifor.

A view into the peephole taken before the renovation of the display in Mega Spileo. Peek-a-boo! Image: unknown source.

That assiduous collector of bones, Hildegard von Bingen (1098?-1179), acquired a small, unspecified bit of Barbara. It is now kept in a drawer along with some other bits and bobs in the parish church of Eibingen in Germany.

The drawer containing part of Hildegard von Bingen's collection of relics. The item top middle is something from Saint Barbara. Image: unknown source.

Which brings us to the end of our relic hunt, with our doubts about the historicity of Barbara unresolved.

Ideas into action

Despite this lack of any credible historical foundation, or any credible authenticity in her relics, she became a popular saint in both the Catholic and Orthodox faiths.

Among other things, Saint Barbara became the patron saint of artillerymen, armourers, military engineers, gunsmiths, miners and anyone else associated with explosives, presumably on account of the vaporisation of Dioscorus in a big flash and bang. Her day is marked by artillery companies and regiments in armies across the world.

Her most consistent followers are to be found among the miners and tunnelers of the world. In Europe, a shrine to her can usually be found at locations where they have been busy. The erection of the shrine to her, first temporary then permanent, is one of the first tasks at the start of a tunneling or mining project. Men who work in constant danger appeal to whatever protection they can get.

As we can see from the large crowds that take part in her pilgrimages and processions, Saint Barbara has an emotional reality that transcends all our empirical, earthly mockery. That emotional reality is as real as her physical existence is questionable. Here is one tiny example of the depth of devotion that surrounds her:

The entrance to a pressure tunnel from an alpine reservoir in Switzerland that takes water down to the hydroelectric turbines in the valley. The shrine to St Barbara is on the right of the entrance. Image: ©FoS.

The shrine to St Barbara in close-up. The statue portrays her holding her unique symbol, the tower in which she was imprisoned. The shrine is maintained with great devotion even though this project finished nearly 20 years before the photograph was taken. It is decorated with artificial flowers and contains a small decorated vase for fresh flowers (currently empty: this was taken in October). There are many small objects, mostly attractive stones but frequently wild-flowers that have been left by passers-by – one of them your mocking author. Why? No idea. It just seemed the right thing to do at the time. It seemed to be a 'place where prayer has been valid' [T.S. Eliot, 'Little Gidding'] or a 'serious house on serious earth' [Philip Larkin, 'Church Going']: respectful atheism does not negate that or rebuff the piety of others. Images: ©FoS.

The same shrine in July of the previous year with a completely different decoration of artificial flowers. There are fresh flowers in the vase and a number of candles to illuminate her image and cast their flicker across the valley through the alpine night. Image: ©FoS.

Leaping from the small to the huge in one bound: the greatest recent tunnelling project in Switzerland, the new Gotthard rail tunnels, have a number of shrines to Saint Barbara that were set up at various points during the project. Here is one:

A shrine to Saint Barbara at the entrance to the Gotthard Basistunnel in Erstfeld, photographed in March 2012. Image: ©Keystone/SRF [There are some more interesting images at the link].

In the face of such heartfelt adoration and such straightforward faith our empiricism wilts. Do the facts of her life and her death or even her existence matter at all, when the idea alone is so strong that it moves and tunnels mountains?

A detail from the Altarpiece of Saint Barbara, 1447, showing Saint Barbara holding her attribute of a tower, with Saints Felix (left) and Adauctus (right), two early martyrs (303?) who were beheaded together for their Christian faith. Both of them are as historically obscure as Saint Barbara herself.

Update 13.12.2017

Photographs of the Altarpiece of Saint Barbara, 1447, taken sometime between 1900 and 1920, showing the two outside wings that are now lost or destroyed. All images: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, online.

A full view of the altarpiece with the side panels extended. The chronology of the story of Saint Barbara runs from left to right across the top panels: third window in tower – anger of Dioscurus – destruction of idols – Saint Barbara escapes from the tower – betrayed by shepherd – discovery by father. Then left to right across the bottom panels: torture with the fork – torture by fire – torture by beating and amputation – dragging behind a horse – beheading – destruction of Dioscurus.

The left panel of the altarpiece (details below).

In her father's absence Saint Barbara orders the workmen to add the third window to her tower, symbolising the Holy Trinity.

The argument between Saint Barbara and her father.

Saint Barbara being tortured with the fork.

Saint Barbara being tortured with burning torches.

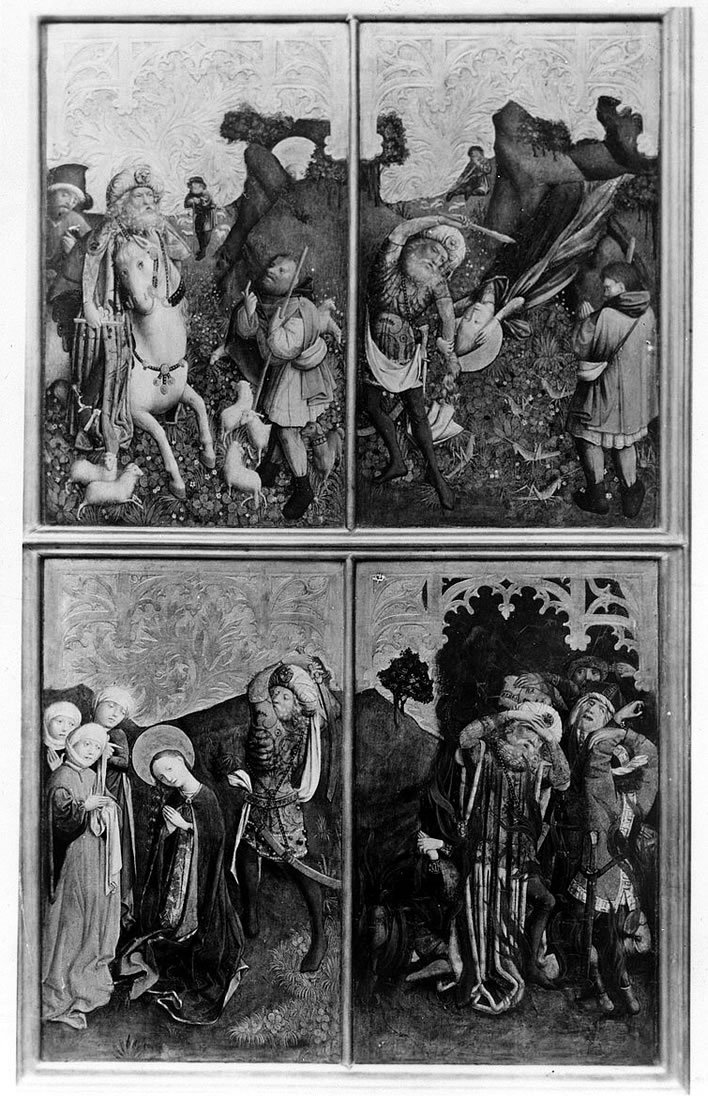

The right panel of the altarpiece (details below).

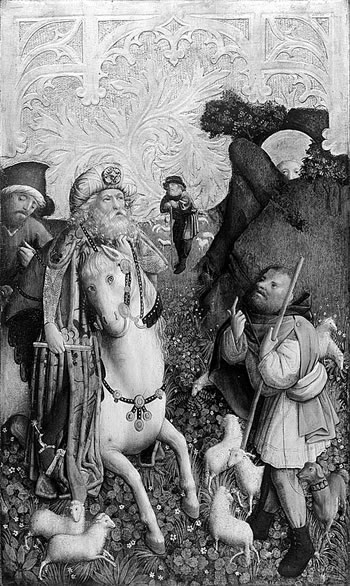

A shepherd betrays the whereabouts of Saint Barbara's hideout to her father.

Saint Barbara's father drags her from her hiding place. The sheep of the treacherous shepherd are turned into grasshoppers or locusts.

Saint Barbara being beheaded by her father.

Saint Barbara's father is struck by lightning.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!