20 April 1945: Hitler's last birthday

Posted by Richard on UTC 2018-04-20 06:32

Victor Klemperer's diary

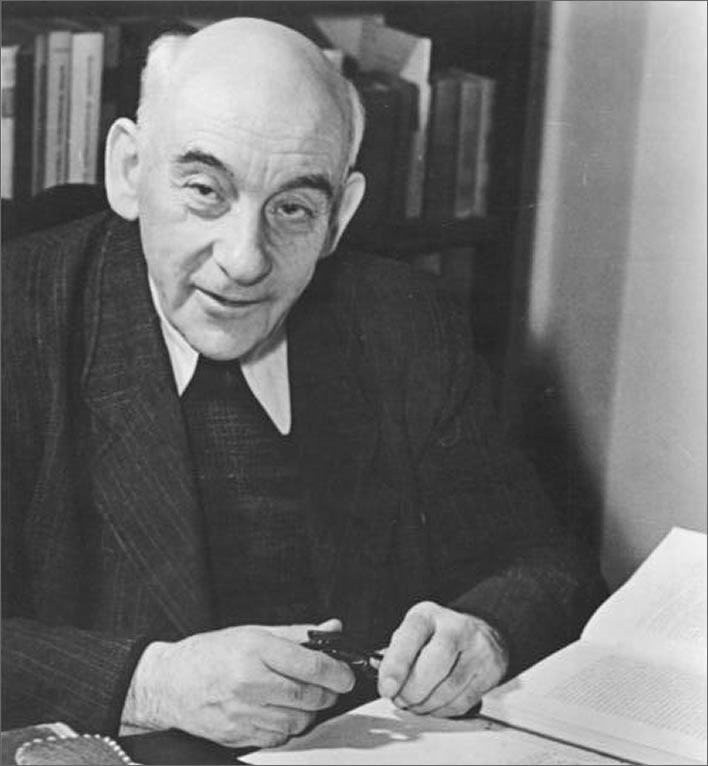

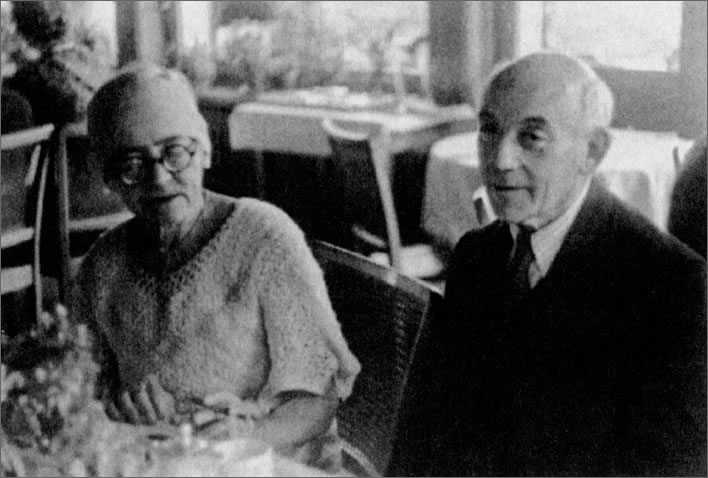

Victor Klemperer (1881-1960) was Professor of Romance Language and Literature at the Technische Hochschule in Dresden. His wife Eva (1882-1951, née Schlemmer) was a pianist. They married in 1906.

Eva and Victor Klemperer with their car in 1935, two years after Hitler's seizure of power in Germany. The trips in the car brought them pleasant hours of distraction and apparent freedom, but the ownership and continued use of the vehicle became impossible as the Klemperers' situation worsened. Image: Archiv Hadwig Klemperer / Aufbau Verlag.

It is fair to say that he was not an outstanding academic in a fashionable field at an outstanding institution. He would have quickly faded from human memory were it not for the diary that he kept from 1933-1945, covering the time between Hitler's seizure of power in Germany and the moment when the 'Thousand Year Empire' collapsed in rubble.

Victor Klemperer in 1952. After the war the Klemperers returned to Dresden. A lifelong socialist, he threw in his lot with the new East German government. His willing embrace of yet one more tyranny after only just surviving the horrors of its predecessor is difficult to explain briefly. The DDR gave him the status he craved with professorships and honours, but outside the cultural island of the DDR his academic work lost relevance. Image: Bundesarchiv.

Klemperer's diary is not conventional history writing. It is a fine-grained and immediate record of what he and his wife experienced during those times. As the Nazi cancer spread into all aspects of life, both private and public, the Jew Klemperer's existence became more and more threatened. The fact that his wife was Aryan prolonged that existence on numerous occasions, but at any time he could have been sent to the death camps or executed on the spot for some trivial or even imagined offence.

If found, his diary would have been an immediate death sentence. The couple endured many searches during those dozen years but by some miracle the diary was never discovered. Over the years, sections of it were deposited with trusted friends – somehow the diary survived the many relocations, disruptions and wanderings of that period. It even survived the great firebombing of Dresden in 1945.

Klemperer's doggedness in recording the quotidian evils of the Nazi years is astonishing. In the most terrible and depressing circumstances we find him scribbling away – if he couldn't scribble directly in his diary he scribbled notes he would later use to write up the diary at the next opportunity. He was particularly fascinated by the development and use of the Nazi-specific terminology of those years. After the war Klemperer wrote a book LTI, LTI=Lingua Tertii Imperii, 'The Language of the Third Reich', which collected together his philological observations from this period.

The following extracts from his diary describe the period from the middle of February to the middle of May 1945, that is, a time seventy-three years ago. As it happens, Easter Day also fell on 1 April that year. This was the period in which that final collapse of Germany took place.

Mise-en-scène

At the beginning of the period, its conclusion, the destruction of Nazi Germany, was already clearly in sight. The Klemperers, along with many intellectuals in their circle of friends had been expecting the regime to fall apart almost since it seized power 1933. Something so monstrous surely could not last. But last it did until this moment, twelve terrible years later, when the noose was finally closing around the regime.

Despite the hope, despite the confidence that the end was now only a matter of time, there were terrible times ahead for the Klemperers in the last five months of the war. These hardships came upon them at a time when they were both in their mid-sixties.

The start of our period is marked by the firebombing of Dresden on 13 and 14 February 1945. The Klemperers survived the attack but became refugees. They had a house in the suburbs of Dresden. It was still intact but had been taken from them by the Nazis years before. Homeless now, they set off on a long, wandering journey around southern Germany that would last four months. That flight was no orderly journey but a series of speculative jumps in search of shelter, safety and anonymity. Routes were sometimes retraced – all of their journeys were adventures with uncertain ends.

They travelled mostly on trains, which were usually heaving with other displaced people – it is a cause for wonder that so many of these rail services were still running under the circumstances. Sometimes they even travelled on the backs of milk trucks; long stretches were covered as foot marches, laden with a backpack and a suitcase in each hand.

They met the people of Germany in their milling masses: there were overnight stays in railway station waiting rooms and air raid shelters amid the teeming multitudes who were also underway.

Unlike the generalities of the great histories, Klemperer's minutely detailed account gives us a snapshot of the minds of the people of Germany in these terrible times: there were the Hitler believers would could not accept what was happening; there were the people who had simply gone along with it all and who were now hoping to be able to go along with whatever might succeed it; there were the opponents of the regime who, despite everything, had somehow survived up to this point. And all shades in between.

During those four months of wandering the war finally staggered to an end. Hitler had his last birthday on 20 April (56 years old) and killed himself in the Berlin bunker on 30 April. Goebbels killed himself and his family the following day. Mussolini had been captured and executed on 28 April, the Italian army surrendered the day after. The German forces in Berlin surrendered on 2 May and Germany as a whole capitulated on 8 May. At that moment the German state ceased to exist.

The firebombing of Dresden 13-14 February 1945

The Klemperers' luck had seen them through a dozen years of Nazi terror. It seems incongruous to call all the hardships and sufferings they had undergone in that period 'luck', but the main thing is they were still alive and in that fact alone – compared with millions of others – they had been very lucky. Klemperer's honesty during the years of attrition is remarkable: 'Yes, I'm still alive!', he often exults to himself when the finger of fate points elsewhere and some unfortunate rather than him gets taken away to their doom. The Klemperers would also have an astonishing series of lucky escapes during their wanderings.

Even the firebombing of Dresden on 14 and 15 February was lucky for them. The morning of just the day before, 13 February, the Gestapo in Dresden had received the order to round up the last remaining Jews in the city. Rational people reading this will recall that the death camps in the east had been taken or were just about to be taken and think to themselves: 'What was the point?'

Well, the Klemperers would have just been taken somewhere out of view and executed. It is one of the most difficult things for moderns to accept, that the murder machine simply kept on turning, the Endlösung kept on being implemented and the Gestapo and the SS kept on doing their duty even when the impending defeat of Germany was so obvious. We have to realise that this lawless behaviour was not an aberration. During those twelve years it had become normal – it was the equivalent of the now iconic but apocryphal 'carry on' signs attributed to that period: 'Carry on and keep killing'.

Some Nazi theorists even held that the campaign of mass murder should be pursued discretely to its end so that another, 'cleansed' Reich could arise after its predecessor had done the necessary dirty work, when all would be forgiven by a grateful German people.

In the general chaos of the Dresden bombing the Klemperers had their opportunity: Victor removed the Judenstern, the yellow Star of David, from his coat and he and Eva became refugees. That act alone, were it to be discovered, was a death sentence. Thus foremost among all the other fears of the next few weeks would be the fear of recognition: Klemperer the teacher was widely known in an around Dresden. He was terrified that someone would recognise him and denounce him, in which case, as a Jew, he had nothing to expect but death.

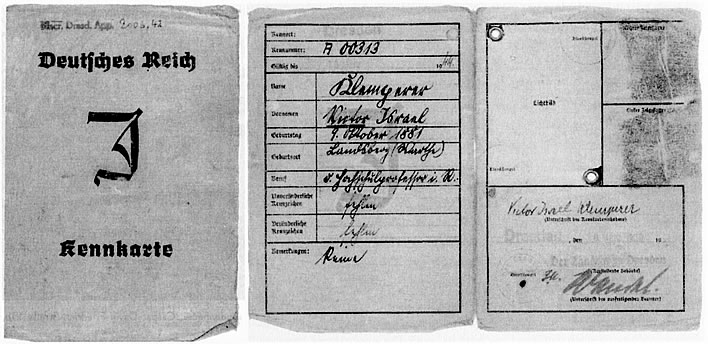

Top: Victor Klemperer's ID card from the 1940s. The large 'J' on the cover identified him as a Jew, as did the obligatory middle name 'Israel' that was given to all Jewish men; women were given 'Sara' as their middle name. The 'J' was even repeated on the inner information page, just in case anyone could be in any doubt.

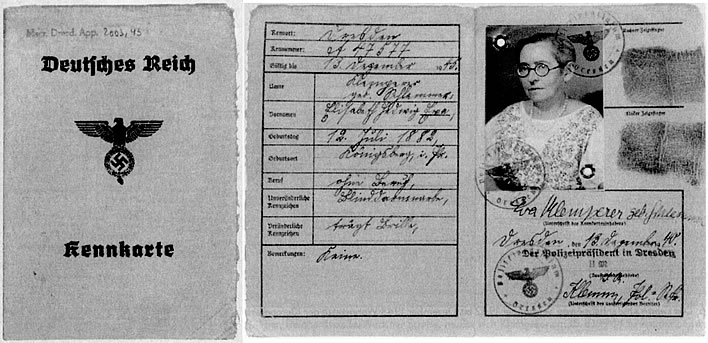

Bottom: Eva Klemperer was Aryan and so carried a normal German ID card. The Mischehe, 'mixed marriage', with her kept him alive in the early years. They received different allocations of ration coupons. The coupons given to Jews were not designed to support life, whereas Eva's Aryan rations were slightly better. The pooled ration coupons kept Victor alive. Image: Deutsche Fotothek / Aufbau Verlag.

The first refuge: Agnes Scholze in Piskowitz

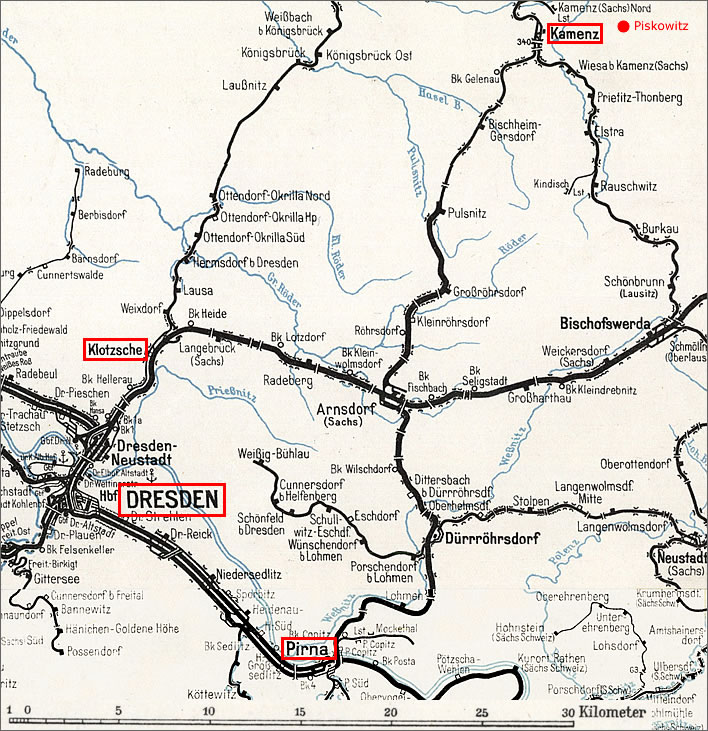

After the firebombing of Dresden the Klemperers were evacuated to Klotzsche, a northern suburb of Dresden. After two nights there they took the train to Kamenz and then walked the 8 km or so to Piskowitz (now Pěskecy).

Piskowitz was the home of Agnes Scholze, who had been the Klemperers' loyal maid between 1925 and 1929. She had been widowed in 1944 and was now running a small farm in this small village – a perfect place for the Klemperers to evade recognition. The Klemperers had kept in touch over the years with Agnes, who had kept up the supply of her successors from the village girls: when one girl married her successor arrived soon after. The Klemperers would find a warm welcome in Piskowotz and could hole up there until the war was over.

The people in Piskowitz were Sorbs (or Wends, as they are sometimes known), who spoke their own impenetrable West-Slavic dialect and who formed a close-knit community. No non-Sorb could infiltrate that community.

They were decidedly anti-Nazi, despite the immense brainwashing of the period. They listened at will to radio broadcasts from all sides and, unlike everyone else in Germany, had no fear in their tight communities of denunciation and death from this crime. Furthermore, the waves of refugees passing through from the east brought eyewitness accounts that never made the official German media.

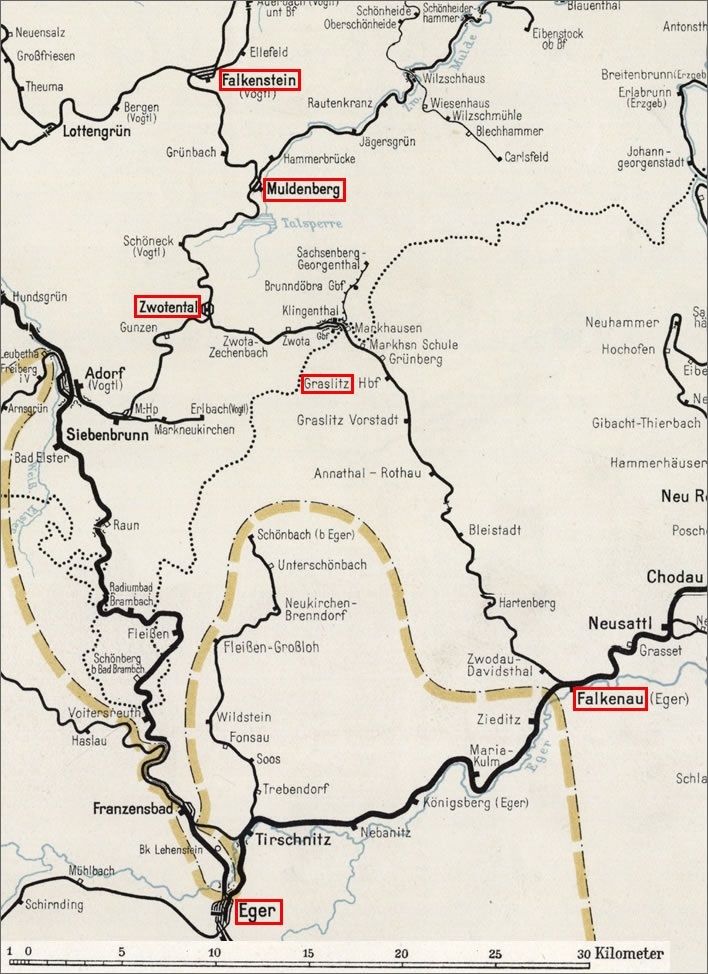

After the bombing of Dresden: the Klemperers' flight to Piskowitz. Dresden — Klotzsche (15-17.02) — Kamenz (18.02) — Piskowitz (18.02). They stayed with Agnes Scholze until 04.03. —Pirna (04.03). They stayed overnight with Annemarie Dreßel.

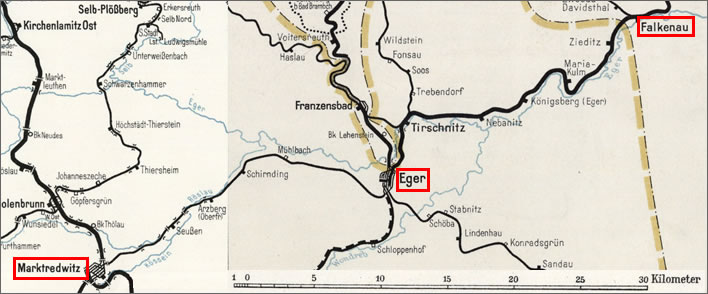

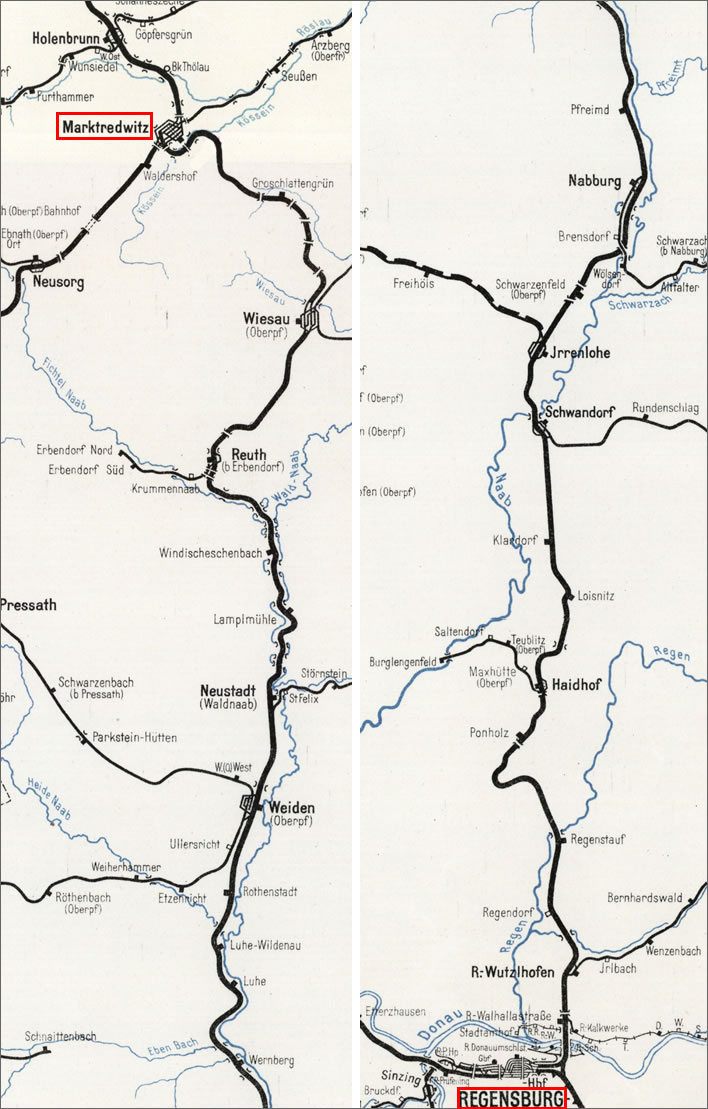

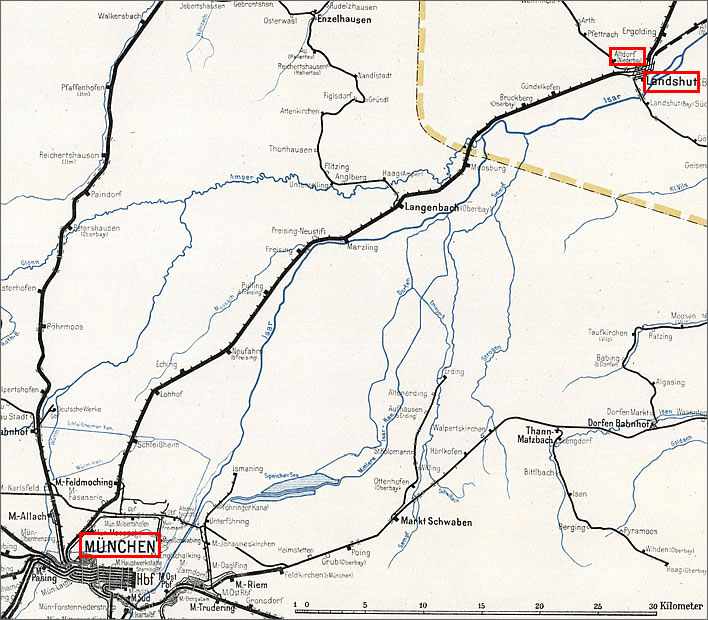

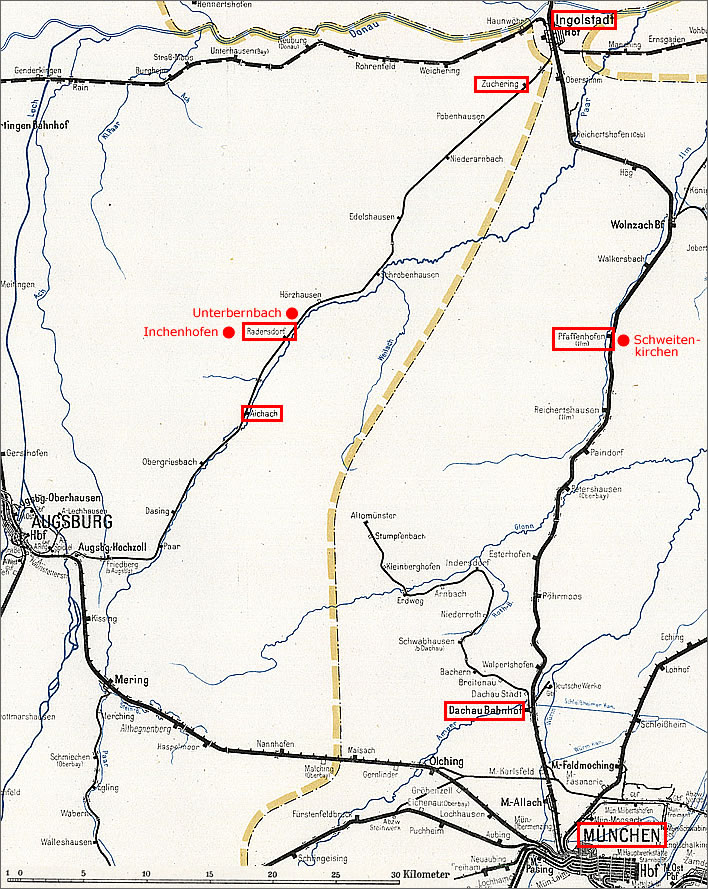

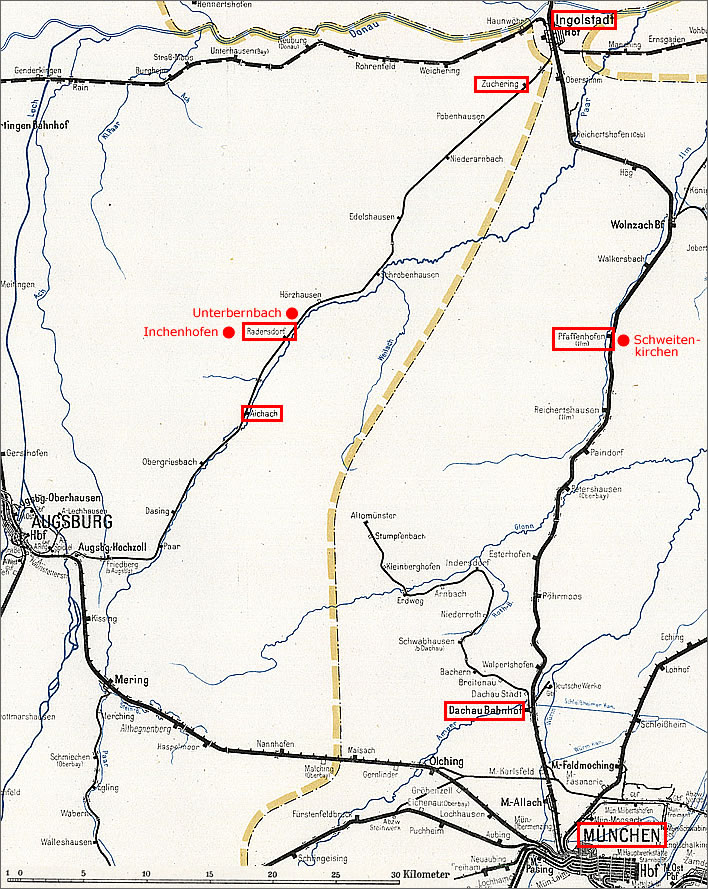

All the maps in this article are based on and adapted from the 'Eisenbahnkarten Deutschland' from the website landkartenarchive.de and generally show the network as it was around 1944.

The second refuge: Hans Scherner in Falkenstein

The Klemperers spent three pleasant weeks there; they felt relatively safe after years of living in fear. But it was not to last – the eastern front had arrived on their doorstep. One lunchtime the order came to eject all foreigners living in Piskowitz by that evening: their accommodation was required for fighting troops. A vehicle arrived and took the Klemperers to the nearby town of Kamenz. From there they started their journey to Falkenstein.

Why Falkenstein? The pharmacist in Falkenstein was Johannes (Hans) Scherner. He and his wife had been close friends of the Klemperers since 1916.

After leaving Kamenz the Klemperers travelled by train at first to Pirna, where they stayed overnight with their old friends the Dreßels. Victor deposited some of his precious diary with them. The Dreßels did not have enough space to accommodate them for any period, so, setting off on 5 March they made a series of hazardous train journeys with air raids on stations and low-level attacks on trains before they managed to arrive at Falkenstein and the Scherners on the following day.

They stayed there for nearly a month in relative safety, but they had to leave when their rooms in the pharmacy were taken up by two apprentices sent from Berlin.

The Klemperers' journey to Falkenstein: Pirna (05.03) — Zwotental, Falkenstein (06.03). They stayed with Hans Scherner until 03.04, when they left for Falkenau. Falkenstein (03.04) — Muldenberg — Zwotental — Graslitz —Falkenau, but it was impossible for them to stay there.

The flight to Munich: in search of anonymity

On 3 April they left Falkenstein for Falkenau in the hope that friends there could put them up, but that was not to be. They dare not stay here: there was a Nazi fanatic living in one of the apartments who would have surely betrayed them.

In Falkenau they decided to make their way to Munich. But now, as the eastern front rolled inexorably towards them, the Klemperers became swept up in the chaos of the collapsing German empire: destroyed lines, continual Allied attacks on trains and stations and immense numbers of refugees fleeing from the warzone and the advancing Russian army.

From Falkenau the Klemperers headed for Munich. Falkenau (03.04) — Eger — Marktredwitz. It was there that they experienced their first overnight stay in the waiting room of the station.

We pick up on Victor's diary entries in Marktredwitz on Tuesday 3 April 1945, on their way to Munich. This would be the first of the seven nights in waiting rooms, air raid shelters and under attack on trains that they would suffer in the course of the next ten days.

The first waiting room night in Marktredwitz had made a great impression on me because of the crowding and the muddle of the groups on the floor. Soldiers, civilians, men, women, children, blankets, suitcases, kitbags, rucksacks, legs, heads, all intertwined; the painterly centre was a girl and a young soldier sleeping tenderly shoulder to shoulder.

The following morning, 4 April, they left Marktredwitz at seven-thirty on the train and arrived in Regensburg at one-thirty, after many stops and alarms.

Heading southward on the line to Munich: Marktredwitz (04.04) — Regensburg (04.04), about 130 km, then on southwards towards Munich.

A delayed departure from Regensburg got them only as far as Landshut. The track from Landshut had been damaged and they had to struggle on foot the 4 km to Altdorf, the next station on the line after the bombed section. They each had a backpack and a heavy suitcase in each hand, the pattern for all the marches they would have to endure.

Arriving at Altdorf, they battled their way amidst the struggling masses to get on the Munich train:

We were in a very large second-class compartment with a lot of space between the benches. It was all difficult to make out in the darkness. We got places on the upholstered seats and there was room to put down our luggage in front of us. Conversations went back and forth in the darkness. A young man beside me: My father had always believed in victory, never listened to me. But now even he doesn't believe anymore … Bolshevism and international Jewry are the victors… A young woman on the upholstered seats some distance away: She still believed in victory, she had faith in the Führer, her husband was fighting in Breslau and she believed … the train started to move at about eleven o'clock;

Regensburg (04.04) to Landshut (04.04), about 50 km. The track had been damaged just after the station in Landshut (04.04) —4 km walk to Altdorf, then train to Munich. Arrived (05.04)

After yet another change of train and another struggle with their fellow passengers at Moosach they finally arrived in Munich at four-forty-five in the morning:

On Thursday 5 April we had our first stop in Munich. The station building, the huge roofs of the station hall fantastically, dreadfully destroyed. At a great depth beneath it, giving a feeling of safety, an immense bunker, whole catacombs divided up by a huge longitudinal corridor with large rooms off to the sides, subterranean waiting rooms, an NSV-post, a first-aid post, lavatories and washrooms. Overcrowded with people lying down, sitting; staff, railway police often very rude: 'Wake up! Legs down! Other people want to sit, too … Get the stretcher out of the way, get back to your place… This is your fourth day here; if I see you again, you'll be coming with me to the police station! … ' The Marktredwitz scene enlarged and varied fifty times.

NSV is the acronym of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, the 'National Socialist People's Welfare', a social engineering and welfare organization with strong Nazi ideological flavour.

All in all the Klemperers would spend a total of three nights in the hell of the Munich air raid bunker:

We saw and experienced that scene three times in all. Eva lay on her mangy fur coat spread out on the bare stone floor of the cooler outer passage, between Italians and Slavs (who were only allowed in the outer rooms), I sat cramped in the rooms, where it was stuffy and it stank, but it was warm. For me, of course, sleep was limited to a very few hours.

In a room right at the back the NSV served coffee and bread in the morning, then at midday and evening soup, a very thin soup, and bread. Everything was served out in a very friendly way, but a record was kept of every ration, which surprised and embarrassed us the third time we appeared: 'What, are you still here?!' Quite depressing, but just a prelude to our experiences in Aichach and Inchenhofen.

They stayed in the bunker until it was morning, then made a short excursion into the city:

We said to ourselves: a terribly damaged city, but, unlike Dresden, one that was still alive; but we also said to ourselves: there is still a lot of damage to be done here. Since then, Munich has been repeatedly bombed.

A view of the destruction left in the centre of Munich in 1945. Image: Unknown source.

The Klemperers got into a discussion with a couple from Berlin, who between them held remarkably contrary opinions about the current situation:

At lunch we shared our table with a married couple from Berlin. He said: People were saying that Hitler had shot himself, she: They were saying, the 'turning point' would come in four days, the new weapons, the new offensive. These were the two extreme ends of the vox populi which can be heard everywhere. Or more exactly: could be heard. Because in the last few days the optimistic belief in a final victory is as good as silent (at least among the people around us) and the defeatist remarks are as difficult to count and distinguish from each other as the air-raid alarms: Everywhere you can hear sirens, everywhere there are low-flying aircraft, everywhere the distant and now not so distant noise of the front, everywhere the sigh: 'If only the Americans would come soon!'

The reactions of the locals to the refugee 'plague of locusts' differed markedly from place to place:

In the villages the extremes are side-by-side. That is, there is clearly plenty of everything, but although some people good-naturedly share a part of their astonishing riches, milk, bread, fruit buns, sausage, macaroni, semolina (without ration cards and made with egg), others hard-heartedly keep everything back, expecting a coming famine and viewing the countless refugees flooding the country (like fleas on the head of a bathed dog) as a plague of lawless locusts.

'fruit buns': Rohrnudeln, a bread bun usually filled with fruit such as apples or pears and baked in the oven – a Bavarian speciality.

A failed detour to Schweitenkirkchen

The Klemperers' long wanderings around Upper Bavaria, part 1: Arrived in Munich from Landshut (05.04) — Dachau (05.04) — Pfaffenhofen (05.04), overnight in waiting room — milk cart to Schweitenkirchen (05.04) — walk back to Pfaffenhofen (06.04) — Munich (07-08.04), 2nd and 3rd overnight stay in the station bunker.

They decided to go to Schweitenkirchen, where their friends the Burkhardts lived. The route there was not simple: at four in the afternoon they took a train from Munich via Dachau to Pfaffenhofen.

They spent the night in the waiting room on Pfaffenhofen station. In Pfaffenhofen the buses were not running. On the afternoon of 6 April they travelled with the 'Millimann ', the milk collection truck that also accepted passengers. The trip cost nothing, but passengers travelled sitting on the milk cans and at every collection point had to dismount to allow more cans to be loaded. The milk collection journey took them in a wide detour.

They finally arrived in Schweitenkirchen that evening, only to find that the Burkhardts could take them for one night but no longer – a Nazi sympathiser lived in the same house and would surely report them.

Nevertheless, they had a good evening meal, a good night sharing a broad sofa and a good breakfast. That evening they listened to British radio and were given hope for the rapid progress of the Anglo-American troops. Buoyed by this hope they decided to leave for Munich and stay with their old friends, the Vosslers.

Nevertheless, we got such a good rest that we could get our breath and our courage back. I was able to dry shoes and socks and relax in warm socks and slippers; we got coffee, we got a substantial hot supper, we could stay for the night and shared a very wide sofa; the next morning I was able to have a shave, there was breakfast as well – and along with all of that they were friendly to us. In the evening we listened together to the English radio and drew hope from the advance of the Anglo-Americans. We decided to return to Munich and to call on Vossler …

On Saturday, 7 April, Herr Burkhardt accompanied them the 2 km to the junction of the Munich-Nuremberg motorway. After a long time with no pickups they decided to walk the 7 km to Pfaffenhofen.

They came across a military vehicle that was being repaired by the driver. A soldier was standing and watching. They kept going, but soon the soldier caught them up and accompanied them to Pfaffenhofen:

We had not gone much farther before the soldier caught up with us, took one of my bags with easy grace, joined us and we chatted agreeably the whole way. He only had one hand, the other he had lost in Normandy. He had been taken prisoner there, then sent to the USA and then exchanged. He was eighteen, big and strong, from the Waterkant, but he liked it here, he had found a girl here.

Only – would he have any future at all? He was in the Waffen-SS and what will happen to the SS, when… everyone knew the answer to that. But the Führer didn't deserve to be defeated, he had had such good intentions and organized everything so well. And he would not be defeated either. The setbacks so far had been the result of treachery, there had been treachery long before 20 July and now, on the Führer's birthday, on 20 April, our new offensive would begin and liberate the East.

The Waterkant, is a Low German (Plattdeutsch) dialect term applied to the North Sea coast of Germany.

'long before 20 July' 1944, the date of the assassination attempt on Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg and others.

The soldier is one of many Klemperer encountered who held a mystic expectation of 20 April, Hitler's birthday. At its core, National Socialism was a cult held together by religious levels of belief. We see this in the soldier's combination of rationality with the traces left behind by the quasi-religious propaganda of the Nazi years:

Nevertheless, he did not seem quite certain and was glad to be consoled by me: As a bricklayer he could always earn a living and he would surely be able to work with one hand and a prosthesis.

I asked him what it had been like in America. 'Good,' he could not deny it, good rations, decent treatment under German officers … But of course the Americans had done that only for propaganda purposes, so that those exchanged would afterwards say good things about the USA when they got home. In the young man's head naturally rational ideas were jumbled up with all the propaganda that had been drummed into him.

However, the Nazi sympathies of the soldier were an exception according to Klemperer:

We soon reached Pfaffenhofen; at the edge of the town he turned off towards his billet. His last word: If things went really badly, then he would volunteer for the front again. I believe that was the very last pro-Nazi, warrior voice that I heard.

From that point on there were only defeatist expressions, some disguised, some open, but ever more frequently until you could no more keep count of them than you could of the air raid alarms. Apart from very rare, purely official exceptions, Heil Hitler is no longer heard. Everyone says (and said already [when we were] in Munich), Grüß Gott and Auf Wiedersehen.

'Grüß Gott ' is the traditional greeting in the predominantly Catholic areas of southern Germany and is particularly associated with Bavaria.

'Only defeatist expressions': Klemperer may have misjudged the situation in this respect. He would still meet plenty of Nazi belligerents during the remainder of his wanderings. In this respect we have to remember that Klemperer was writing his diary more or less in realtime, but although he would frequently retrospectively write up his notes, we can expect his opinions to be overtaken by later events.

In Pfaffenhofen there was an air raid alarm and the Klemperers found themselves involved in another conversation in a cellar – yet another conversation with a bitter and confused German, but still expressing hope in the religious salvation the Hitler's birthday would bring:

Hardly had we entered Pfaffenhofen at about twelve-thirty than there was a minor alarm; we had just sat down for lunch in Bräuhaus Müller in the main square, when there was a major alarm and we had to go down to the spacious cellar.

Conversation with one of those present: 'Just how will the war end?' Smirking answer: 'I can't tell you that – silence is golden – you never know who you're talking to.' As I said: There are too many remarks of that sort to record any more.

Refugees whom you have barely known a minute, on the milk truck to Schweitenkirchen, on a railway platform … talk bitterly, accusingly, waiting for the end – and most of all the farmers! When can the Americans get here … if only they would come… Dug a hole for a bazooka? We'll just take a towel with us, so we can surrender right away … This madness, that we are expected to fight on! But he has every general and every mayor who doesn't go on fighting shot … Just eight to fourteen days, no longer, then they'll be here… My lieutenant says, the new offensive is coming on the twentieth and then the East will be free in four weeks, but I don't believe it anymore … The new weapon? We've heard about that for two years now… If only they were already here, the Americans… etc., etc., as unceasing as the alarms and the planes.

'Coming on the twentieth': Hitler's birthday, yet again.

They left Pfaffenhofen at seven in the evening on 7 April and arrived in Munich late that evening. They spent their second night in the bunker in the station.

Munich, again

As usual, sleep did not last long in the bunker:

Sunday 8 April. In Munich we were woken after five o'clock by the cleaners and guards. We again went to the NSV post for coffee, then went to an hotel that opened early (Excelsior) in a badly damaged building near the station. We sat there quietly for a while over breakfast. Then came the trip out to see Vossler.

They found Vossler and his wife, but they could not put them up, which meant that they spent their third night in the Munich station bunker sleeping on the ground. There was a air raid alarm at one in the morning and even more peopled streamed into the bunker. Nevertheless, the Klemperers were happy to be there: 'It would have been no fun in one of the guest houses in the city'.

The following morning, 9 April, they breakfasted again in the Hotel Excelsior. There they met a couple from Austria, who presented them with another glimpse into a sample of the German mind:

They were from Graz, the man, a minor civil servant, was on his way to Berlin to claim his unpaid salary; they did not know where they were going to end up next or whether he would be 'redeployed'.

It was amusing to observe the way disconnected scraps of memorised and officially required LTI still floated around like islands in the man's disillusioned and embittered head.

The bigwigs had fled Graz in their cars, leaving the little people to look out for themselves as best they could. And it was the little people who had to suffer the consequences, everything: the suffering, the war … But, of course, it will all come right. The Führer had said, hadn't he, that there is no such thing as impossible and that we were Europe's bulwark against Bolshevism.

We let the couple go on talking and took a friendly leave of them; they will certainly very quickly and very willingly find their way into the Fourth Reich.

Aichach and environs

The local authorities directed them to go to Aichach, a town of which neither of them had ever heard. Getting their tickets (queues) and the rationing coupons (from an office in another part of the city, more queues) took time and cost nerves. Finally, at three in the afternoon they left on the train to Dachau. They were advised not to continue that night to Ingolstadt, the waiting room had been destroyed in the latest air-raid.

They spent the night of 9 April in the hellish waiting room on Dachau station. The following morning they took the train to Ingolstadt – which turned out to be intact after all – arriving at eleven-thirty.

The following morning, 10 April, an air raid damaged the line between Ingolstadt and the next station, Zuchering. There was nothing for it but for the Klemperers to walk the 9 km there. On the march they met a soldier, yet another of the delusional Hitler worshippers still remaining – another one waiting for Hitler's birthday to bring the turnaround in Germany's fortunes:

For a while we walked along together with a soldier; the man, a complete exception here, still had hopes of 20 April. (I am writing this on the nineteenth, Russians and Anglo-Americans are simultaneously closing in on Berlin; I, too, am now almost superstitiously on edge, waiting to see what this 20 April will bring for the Germans or the enemy.)

During a rest stop just before they arrived in Zuchering in the late afternoon they met another soldier guarding a bridge. This man had a diametrically opposite opinion:

The soldier we met before is billeted here. He is a Württemberger from his accent, no longer young and from a good social class. He spoke very openly about the war, which was unquestionably lost, about the senseless murder of continued fighting, about Hitler's 'megalomania'. Then he disappeared and brought us a large piece of dark bread and a quarter-pound of butter as a present. We should take it in good conscience, for when more than a hundred men are being catered for – he was evidently an army cook – there was always something left over.

The train from Zuchering got them to Aichach at one-thirty on the morning of 11 April. Another night in a station waiting room. Unfortunately, the official plans had changed and they were no longer welcome in Aichach:

We arrived at Aichach at one-thirty in the morning. This was the seventh and final waiting room or train night of our days of flight, but the end of our odyssey had not yet arrived. … Eva returned with this news: Munich had sent us to Aichach by mistake, the district was already closed to refugees; but since we were already here, they would look after us. However, we must immediately proceed on foot to Inchenhofen with a special letter of recommendation.

Their journey to Inchenhofen was as unpleasant as their journey to Aichach had been. There were continual alerts and the noise of bombing. 'If only the Americans would come!' Events were going from bad to worse, their reception in Inchenhofen was frosty:

… We finally got to the inn in Inchenhofen in a really desolate state. The young landlady, without saying a word, refused us the least bite to eat or drop to drink with just an almost mocking shake of the head, while a party of soldiers billeted there were being served a generous meal.

After a bitter battle to obtain some accommodation in Inchenhofen, in which the authorities had to intervene over their mistreatment by one of the locals, the Klemperers finally got some decent treatment and decent food in the Klosterwirtin inn:

…The fatherly police officer led us to the Klosterwirtin, a more modest inn, already closed, opposite the mayor's house. He negotiated in the kitchen while we sat in the empty restaurant, then he came back, asked whether we would like the sausage warm or cold – 'Whatever is less bother' – gave us some hope for tomorrow and left after much reassurance.

A pig had evidently just been slaughtered; we were reminded of Piskowitz. The good-natured landlady brought us such a quantity of blood and liver sausage, that we were still eating it the day after; she gave us bread, she promised us breakfast and lunch for the next day. She kept her promise, accepted only a very little money for everything and didn't take a single ration coupon from us.

After much studying it was apparent that there was no room for them in Inchenhofen, they had to return to Aichach for further instructions. After a wait of three hours they were taken back to Aichach in an army truck, but no rooms were available.

From there they were sent off to Unterbernbach, a village which, they were told, was 'only a ten minute walk' from the nearest station, Radersdorf. When they finally got there that evening, the ten minutes had turned out to be thirty.

The third refuge: Jakob Flamensbeck in Unterbernbach

We can imagine just how deep this point must have felt for the couple. They had run out of friends who could help them and were now completely reliant on strangers as they fought their way from one disappointment to the next. Fortunately, the dark moment of 12 April was the nadir. From the moment they arrived in Unterbernbach their fortunes began to turn:

We were dead tired by the time we arrived. We asked the way to the Ortsbauernführer; a young person said he would come soon, we should leave our luggage in the hallway and go and wait in the inn opposite. From this moment on things went well for us.

At the inn we were given supper by a friendly landlady. Afterwards, it was already almost dark, we met the Ortsbauernführer, a man called Flamensbeck, a gaunt, grey-haired man, who immediately took care of us with the most touching kindliness (a Quaker, Eva said). Straw beds, pillows and blankets were laid down on the living room floor for us without fuss; we were to stay there until other accommodation had been found for us in the village. We lay down to sleep relieved and happy (especially since the landlady in the inn had provided us with a festive meal: soup, jacket potatoes, bread, cheese, beer). And now the odyssey proper and the worst privations (though not all hardships) were behind us.

The Ortsbauernführer was an administrative position established by the National Socialists. The occupant, usually a local farmer, represented the farming community in a village.

Klemperer writes Jakob Flamensbeck's name in a number of variant spellings. We have consistently used the correct spelling.

The Klemperers stayed two nights with the Flamensbeck family. Their treatment was warm – not only were their physical needs met but they encountered a warm and humane reception.

The Flamensbecks embody the many contradictions in National Socialist Germany. As we have read, their personal generosity led Eva to call them 'Quakers'. They were, however, National Socialists through and through:

The Flamensbeck family, on whose floor we slept for two nights (12-14 April) is a model of friendliness. The man, Deputy Mayor and Ortsbauernführer (Sign on the house: Reichsnährstand. Blut und Boden and underneath Ortsbauernführer), cannot do enough for us, displaying all the while a good-natured dignity. His wife very willing.

A lined face, animated in his movements and speech, speaking a dialect verging on the incomprehensible. A plump older daughter with a boy of about eight, her husband fallen. A younger daughter with a four-week-old bottle-fed child, around whom everything happily and tenderly revolves. The child's father is a young wounded soldier with his arm in a sling. (The same one who told me his lieutenant was talking about a new offensive, whereas he himself did not believe in it.) On the wall the picture of a son missing in Russia.

The father says he is a National Socialist, but things cannot go on like this, peace has to be made, otherwise more blood will be spilled in vain. He is not afraid of the enemy, despite being a Nazi, because he has oppressed no one. However, the teacher says of him that he was the first and most enthusiastic Nazi in the village.

The Reichsnährstand, literally but misleadingly translated as 'Imperial Food Estate' ('estate' here in the sense of, e.g. 'Third Estate') was an organization set up by the National Socialists after their seizure of power in 1933 with the intention of organizing agricultural production. It was rooted in the Blut und Boden, 'Blood and Soil' philosophy that was one of the ideological precursors and later cornerstones of National Socialism.

The Klemperers' long wanderings around Upper Bavaria, part 2: Munich (07-08.04), 2nd and 3rd overnight stay in the station bunker — Dachau (09-10.04), overnight in station waiting room — Ingolstadt (10.04) — walk to Zuchering (10.04) — train to Aichach (11.04), night in the station waiting room — walk to Inchenhofen (12.04) — military truck to Aichach (12.04) — train to Radersdorf and then walk back to Unterbernbach (12.04-17.05), stay for over a month under the aegis of Jakob Flamensbeck.

The return to Dresden: Aichach (18.05) to Munich, the beginning of the journey home.

The mood of the village

Despite the warm charity of the Flamensbeck family, most of the rest of the village was cold to the fate of the refugees. The countless crucifixes by the roads and in farmhouse rooms should not deceive – charity was only superficial:

Even the smallest village has a church and an inn, but at the inn, if it is open at all, everything is refused. There is no fire in the hearth – there is a shortage of coal, but there is wood in excess, it is stacked up in the farmyards, it is collected as waste from the woods by everyone, natives and refugees alike. – they don't have any coffee or a drop of milk – they do, of course, but they just don't want to give it. On the whole they have little time for these strangers and locusts. And the country roads are treeless and dusty and threatened by low-flying aircraft. It is no pleasure walking along them.

On 14 April they were put up with a local farming family. Their stay with them would last just over two weeks. In that family Klemperer observes the confused state of mind of those who only ever got to hear what Dr Goebbels told them and notes their puzzlement now the collapse of Germany was so obviously near:

The farmer asked me once whether the Russians were 'really' so barbarous, whether 'American Jewry' really etc., or whether propaganda was involved. I explained with great tact: The steel industry is not in Jewish hands and by the way, better and more reliable business was done in peacetime than in wartime.

The youngest son-in-law, Asam, wounded for the fifth time, absolutely defeatist, who is living in the house of his mother, who 'has not yet handed it on', yesterday let us listen to the military bulletin with him in the 'Asam House'. The living rooms in the farmhouses are all very similar, quite like those of the Wends [in Piskowitz]: There is always a crucifix corner, there are always pictures from military service.

In Unterbernbach the Klemperers met two remarkable, decidedly anti-Nazi sisters, an absolute contrast to the victims of a dozen years of Nazi propaganda. The manner in which both sides, the Klemperers and the sisters, gradually reveal their inner thoughts to each other is a striking illustration of the caution that was the first requirement for having regime critical thoughts and yet surviving.

The sister whom Klemperer first encountered was Frau Steiner, who kept the local mini-library and who had previously been a teacher:

An even more interesting (and more productive) acquaintanceship … was provided by the teacher Fräulein Haberl and her married sister, Frau Steiner. There is no lending library in Aichach and the public library there is open only in the evening, making it inaccessible for us.

We went to the schoolhouse and I calmly introduced myself as who I am. First we were received by young Frau Steiner. She showed us her books, I noticed several volumes by Vossler so there was an immediate point of contact.

Herr Steiner, at present serving in Ingolstadt, had started a fine-art publishing house. He had previously been in newspaper publishing, but could no longer reconcile that with his convictions – they are devout Catholics. [ …] – Whether I was a 'Pg'? My heart grew lighter. I replied diplomatically that I had already mentioned that I was a student and admirer of Vossler, hence one could imagine my attitude to the regime.

'Pg', abbreviation for Parteigenosse, 'Party Comrade', that is, a member of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP).

After this careful piece of trust building, Klemperer then met Frau Steiner's sister Fräulein Haberl. Judging only from her appearance, Klemperer would have taken her to be a fanatical Nazi:

At about this moment her sister the teacher appeared and she was the greatest surprise. Frau Steiner is soft, dark-eyed with a, so to speak, harmless appearance, I would definitely have judged her sister, with her staring blue eyes, her astonishing blondness, her tight, short clothing and almost military posture, to be a super-Nazi, a fanatical BDM leader, an Amazon, a Nazi partisan. Her rough, brittle voice fitted with all of that.

BDM, Bund Deutscher Mädel, 'League of German Girls', the female equivalent of the Hitler Youth.

In fact she turned out to be just the opposite – a fanatical opponent of the Nazi regime. We wonder how the sisters had managed to survive so long.

The girl is an extremely incautious – I must say here: a fanatical opponent of the Third Reich.

'If you are writing about the language of the Third Reich, don't forget Dachau. Thirteen thousand people have died there in the last three months, most of them of starvation and now they are releasing the rest because there is nothing left for them to eat. They have got up to the letter 'H' with the releases.'

Both women talked about Cossmann, the 'hundred percent' nationalist who died in Theresienstadt. We pretended that we knew nothing about Theresienstadt, but were quite astonished to hear the name mentioned in a village in the middle of Upper Bavaria. […] we got two eggs as a special present and were encouraged to come again.

Cossmann: Paul Nikolaus Cossmann (1869-1942), a German political journalist and editor, a strict Catholic, who was imprisoned by the Nazis twice, dying in the Theresienstadt camp.

United in their dangerous critical sentiments, the Klemperers and the sisters formed a mutual support group:

We went there at eight o'clock in the evening of 19 April and listened to the military bulletin. I said Goebbels would speak today. 'He should be crushed underfoot!' responded the teacher. She was alone, her sister was off purchasing provisions. We want to go there again this evening (20 April); various air raids on Ingolstadt provide a good excuse to enquire after Herr Steiner. The two sisters are also of the opinion that it cannot go on much longer; I myself have meanwhile become doubtful again.

In complete contrast to the ant-Nazi sisters and to his early view of the general defeatist tone of German opinion, Klemperer meets a rabid leftover:

At Flamensbeck's I recently met an elderly south German Landesschütze. He explained the term: A kind of home guard duty for those temporarily unfit for frontline duty, but who have been at the front and are returning to it. The man, rabid in type and character and certainly no hypocrite, was completely convinced of the Hitler cause and of its final victory. How the turning point would come, he had no idea, but he knew that it would come. 'Adolf Hitler' had always managed it, you had to 'believe blindly' in him, one blindly believes in so much that has not stood the test of time as well as the Führer.

Recently a woman who had been bombed out had said to him: 'We have the Führer to thank for that!' He had shouted at her: 'But for him you would not be bombed out, you would have been mincemeat long ago!' It could not be grasped with a slide rule and with common sense, they were no use at all – you simply had to 'believe in the Führer and in victory!'

I was really rather depressed by these speeches. If this belief is widespread and it almost appears as if it were … Then again, Fräulein Haberl says the German army is disintegrating and it's all coming to an end. (In fact, today, 21 April, Germany basically consists of no more than a generously defined Greater Berlin and a part of Bavaria.) But she also says: 'I only fear the German soldiers.'

Amongst all the doom, Dr Goebbels keeps the spirits of the believers up in his speech on the occasion of Hitler's birthday, 20 April:

Today is the Führer's birthday. According to yesterday's military bulletin the Ruhr region together with the army there and its Marshal Model appears to be or is in fact lost: 'The battle is over' – no more, not a single syllable more. The Russians are engaged in a major offensive, the others have Leipzig, Chemnitz, Plauen, are fighting to take Magdeburg. Where could a German counterattack of a decisive size come from? And here in Bavaria Nürnberg has fallen.

But 'Goebbel' (sic) spoke yesterday and quite evidently he made an impression. 'Wonderful!', we should listen to the repeat. We were holding our own, in the new Europe our cities would flourish again. Admittedly he did not say how victory could still be won – but the mood here is evidently bolder than before: Ingolstadt was a strong fortress and Berlin could hold out for months!

Even in this small village in the middle of Upper Bavaria, the Klemperers were not far from the war. In the middle of all this military activity Eva Klemperer noted a particular, bitter irony in their present situation:

Eva says: We're unlucky: going by the last report, Falkenstein must already be in American hands. And we are in Upper Bavaria.

Despite Goebbels' best persuasive efforts on the Führer's birthday, fewer and fewer people still believe in the Nazi Messiah:

I saw an excerpt from Goebbels' birthday speech in the Aichach newspaper. The crucial sentence: Surely we shall not give in now, just at the moment when the 'perverted coalition' of our enemies is about to fall apart' …

That it made young Asam angry goes without saying, but even Flamensbeck was openly angry. A new weapon, an offensive, a turning point – he had believed it all, but 'now he didn't believe in anything anymore'. Peace must at last be made, the present government had to go. Did I think it true that we would all be deported? I talked him out of that, told him that they were whipping up resistance with demagogy. He agreed completely.

In a bitter twist of fate, at that moment, so close to the arrival of peace, a company of SS soldiers were now billeted in Unterbernbach. Fräulein Haberl was concerned at first that someone in the village would report her to the SS. She needn't have worried: when even the SS lose faith the end must be near:

Frau Steiner and her sister said to us recently that they feared only the German soldiers. Now they told us in alarm that eight hundred SS men were expected here. […] The reputation of the Steiner-Haberl sisters was well known in the village and the SS would also be politically active. However, they reported to their and our relief that the mood of the soldiers who had arrived so far in the village and in the schoolhouse was completely defeatist: 'You should hear them grumbling!'

As we might expect, there was only one topic of conversation in the village, but always coloured with worry and uncertainty:

Sunday lunch today: soup with frittate, as much potato salad as we wanted and real chicken! – I was able to be gently yet firmly enlightening. And I found the ground well prepared. Young Asam has been voicing it for a long time and Flamensbeck senior has known it for a long time and is pleased to have me confirm it.

'It', that is everything: the criminal murdering and propaganda, the whole catalogue of the sins of this regime, which has to go. I am very gentle, I avoid every accusation, I avoid all humanistic and pious phrases. I repeat this again and again: Our enemies do better business in peacetime than in war, they don't want to destroy us at all. They were surprised by the war, they want to get rid of our warlike government etc., etc. And always: 'But you know this conversation will cost us our heads, if …'

One more voice, this time from Berlin:

While Eva was sleeping and I wanted to write, the Berliner sat chatting beside me for a long time. Utterly depressed, an extreme opponent of the regime. How many more days could it last?

His home is in Basdorf, 17 km from Alexanderplatz, he is a master joiner, has a wife and child, runs a large business together with his father. Who and what of all that is still there? It is so long since he heard anything.

This deceitful government, deceitful in everything! And so savage: 'I don't know if you know how they treated the Jews in Berlin. These poor people, they were truly excluded from public life. Well, I wouldn't have cared if they had just been excluded from public office! But from everything! They were not allowed into any theatre, they were only allowed to go shopping at certain times; I saw children, ten-year-olds, completely segregated …'

I said: 'It was no doubt the same in every city, it weighs very heavily on me.' He: And did I believe in the Russians' barbarism? I: On the whole, not at all, but there are individual brutes everywhere … the hostility to the SS etc. He: Everyone knew what the SS had on their conscience. He also talked about the collapse of the army. Many were deserting. In Heidelberg he had seen two hanged soldiers … And he spoke about the great quantity of provisions distributed and squandered in Regensburg.

What would the Götterdämmerung be without the Hitler Youth, who became the last resort in those mad days of the endtime:

23 April: A detachment of a Hitler Youth division had arrived from Ansbach together with refugees from there, other troops came and went. Terrible, this Hitler Youth gang. Lads of sixteen, fifteen, even younger ones, completely child-like ones among them, in uniform, a cloak in sack-brown or camouflage colours over their rucksacks; they are supposed to engage the enemy with bazookas. Among them also, in civilian clothes, boys, children rather, who have been brought with them from Ansbach. A few adults as leaders. Children's beds on the benches in the taverns.

The condition of these children of the Hitler Youth in the village was particularly saddening:

They are going around begging for food everywhere, so they must be very badly fed or have no rations at all. Today we overheard one group: 'When the Americans come, at least we'll get something proper to eat!'

We have been able to exchange a couple of words with a few of them. Two […] appear to me to be from good homes and to be decent, innocent boys. I asked one of them, who had been given a couple of potatoes, how old he was: 'Fifteen.' – 'Are you off to the front?' – 'Only the volunteers.' – Are you a volunteer?' – Quite unheroic: 'No.'

[A personal interjection: An old friend of mine, now passed, as a fifteen-year-old member of the Hitler Youth found himself sent to the north-eastern front in these months at the end of the war. He also acted rationally and unheroically: he dumped his uniform, stole a bike and in those last weeks cycled from the north to his home on the south German border, surviving on the kindness of others. Why had he joined the HJ? – That was where all the fun was in 1930s Germany.] Back to Klemperer:

Now that all but the most hard-bitten accepted the inevitability of the collapse of the Third Reich, the burning question was: what then?

Old Tyroller has already asked me twice, what will happen when Russians and Americans meet in Berlin? On both occasions there was the hope in his voice, that Russians and Americans would immediately fall upon one another and engage in bloody battle. That is the degree of confusion that Goebbels has managed to create.

Years of propaganda had embedded itself in the minds of so many Germans that even three days after Hitler had killed himself in the Berlin bunker, the fanatics were still hoping for the mystical turning point, the same mystical turning point that didn't turn up on his mystical birthday:

3 May: At the midday meal Asam told us and then the gloomy Staringer repeated it with greater conviction […] that Hitler was dead, it had been broadcast without any more detail on the radio (on which station?). Asam, however, also added, that he himself did not believe it, only yesterday officers had assured him with the greatest conviction that the 'turning point' would come in fourteen days, it would start from Obersalzberg and would be effected by 'the new weapon'. This belief appears to be ineradicable and still finds new believers. The propaganda was too great and was really a form of mass suggestion.

The village was preparing itself for the arrival of the Americans:

And also – completely incredible but literally true! – the mayor has had the swastika that was over the village coat of arms in the gable of the Amtshaus removed!

As the American forces drew near the anger of the people against their former masters began to break through:

Old Tyroller, […] today spits out his hatred of the Party and of the SS. In a village on the Danube a farmer had removed a bazooka from his house and thrown it into the river. The Mayor and Ortsbauernführer had interceded on his behalf. The SS had hanged all three for betraying the interests of the fatherland … And how they had attacked religion! And the Hitler Youth! … They were against the Bolsheviks but were Bolsheviks themselves!… Frau Wagner, the landlady at the inn, beaming… The same mood at Steiner's and at Flamensbeck's. Old Flamensbeck passionately: They had been 'too radical', they had deviated from their programme, they had not treated religion with consideration …

Waiting for the end

On 30 April 1945 in the Berlin bunker Hitler and Eva Braun killed themselves. Goebbels and his family did so the following day. Speaking in general of the pointless losses of the last months of war Klemperer remarked that in the last war, in which he had fought on the front, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had been at least gentlemen who gave up when all was lost, in order to avoid unnecessary casualties.

In contrast, Hitler had kept the war going in all its pointlessness. We would also add that he killed himself without ending hostilities beforehand, thus allowing events to take their brutal course for at least another week. His people had failed him. Perhaps he just didn't care about them at all. Yes, that's it.

Despite the Klemperers' feeling of relief and gratitude for their survival – gratitude to whom?, the atheist Klemperer asks himself – the deprivation and the cumulated exhaustion of all those months of flight are taking their toll:

… Even hardened cases like ourselves are not just hardened, but also exhausted and literally worn-out – all the misery of our situation: the lack of space, the primitiveness, the dirt, the raggedness of our clothes and of our shoes, the lack of each and every thing (such as shoelaces, knives, bandages, disinfectant, drinks …).

The reworking of history in the German mind proceeds with each day that passes:

1 May, Tuesday: [Dinner with the Wagners, who have the inn opposite Flamenbeck's house.] The landlord was talkative. He told us that he had been the caretaker at the Stiegelbräu brewery in Aichach for fifteen years. He told us proudly that he had never been in the [National Socialist] Party, that he had been a member of a Catholic Gesellenverein and that he had been in fights with the SA and had made himself respected.

To what extent are coats now being turned, how far can anyone be trusted? Now it appears that everyone here was always an enemy of the Party. But if that really had always been so … The bottled-up hatred of the SS appears to be genuine, as does the fact that the people long ago had enough of tyranny and war …

The Gesellenvereine were Catholic societies that had been originally set up in Germany in the second half of the 19th century with the aim of improving the conditions, educational standards and morals of young artisans. The life of the average wandering young male apprentice was not as pure and bucolic as those who only listen to Die schöne Müllerin might believe.

When the Americans did finally arrive, all the propaganda stories that had been related about them floated away:

[On 1 May Victor went shopping in Kühbach.] An American support or repair column was in the church square [ …] black – more precisely: brown – Negro soldiers in grey-greenish, earth-coloured jackets and trousers, all with steel helmets stuck on their heads, swarmed around busily. Village children stood close by and among them. Later I also saw a few blond soldiers, in dark leather jackets. […]

The propaganda stories that had been fed to the German people about the brutality of their opponents – and especially the black troops – evaporated when contact was finally established:

[In a side street I spoke to a young blonde woman:] On the first day the occupation troops had taken everything out of the shops, but their behaviour otherwise had been completely respectable. 'The blacks too?' She beamed with delight. 'They're even friendlier than the others', there's nothing to be afraid of … Did she know anything about the current situation? – Munich had already fallen yesterday evening, 30 April.

I went back to the main square and asked two old ladies (more ladies than women) for information. Again, only more emphatically, the same response to the occupiers, exactly the same beam of delight because the Negroes were especially good-natured enemies. (I recalled all the black children's nurses, policemen and chauffeurs in our life.) And what had been said about the barbarity of these enemies, that all had been nothing but 'sayings', just 'rabble-rousing'. How the populace is being enlightened!

Just as the German state had disappeared, so had its restrictions. From one day to another, the rationing system disappeared. It had been one of the most pressing factors in the Klemperers' existence for so many years, but now the carefully hoarded and counted coupons were just waste paper:

The shops in the town were to remain closed for about a week but I should try my luck around the back, 'across the yard, past the manure heap, that's where you'll find Lechner'. There I met a friendly woman, who straightaway brought me a six-pound loaf. It cost 90 Pfennig. I handed her money and coupons, she refused the coupons, they were worthless.

The theme of the coming war between the USA and Russia had been one of the standard memes of Nazi propaganda. The theory was that the coming war between the two would give the National Socialists a chance to re-establish themselves in Germany. It proved a difficult idea to dissipate, even with such otherwise sane people as Frau Steiner:

[3 May, Thursday morning. Frau Steiner:] In Aichach an American is supposed to have said, they would now be at war with Russia. I talked emphatically to her, she should not let the lying Goebbels propaganda make a fool of her. Eva said: If we keep on hearing it for much longer, we will believe it ourselves. This morning the first words of the Gruber woman: 'They say that the Russians have declared war on the Americans!' […] But there was nevertheless an element of truth in the remark 'we'll end up believing it ourselves'.

Of course, given what we know now about the division of Germany after the war and the tensions of the Cold War that would last for nearly half a century after the end of the war, the public expectation of some sort of antagonism between the Russians and the Western Allies was in fact quite well-founded.

Relocation

On 3 May the Klemperers had some unspecified but bitter argument with their host Frau Gruber and moved out the day after. They went once more to Flamensbeck.

At the Flamensbecks', who sadly, sadly do not have a room in which we could stay, we are not only well fed and kept warm in a well-heated room – today the ground was covered in frost again! – but it is also always the most interesting place.

The sign Ortsbauernführer has disappeared, but people still turn up and Flamensbeck feeds them and puts them up for the night in his barn. Everyone gets soup or a piece of meat or sausage, everyone cuts what they want from the round loaf that lies on the table with the knife next to it. 'It is' says Eva, 'as though people smell his kindness.'

Two soldiers turned up. The older one seemed to Klemperer to have been a student or school teacher, the younger one in commerce. Both were from the Sudetenland and were trying to get home via Ingolstadt and Regensburg. We don't know whether they managed to return, but if they did it is quite likely that they would shortly afterwards be among the millions of Sudeten Germans who were thrown out of the country when the new Russian masters and Czech patriots took over Czechoslovakia.

Yesterday evening Flamensbeck took in two soldiers, unarmed but in uniform, with whom we talked for a long time. Yesterday they had listened to a radio. Everything, including Berlin, had capitulated and Hitler was dead. The student declared: 'If anyone had said that to me, even four weeks ago, I would have shot him dead – but now I don't believe anything anymore…' They had wanted too much, they had overdone things, there had been atrocities, the way people had been treated in Poland and Russia, inhuman! 'But the Führer clearly knew nothing about it', the Führer was not to blame; they say that Himmler was in charge of the government. (Still the faith in Hitler, he undoubtedly had a religious effect on people.) Neither of them really believed anymore in the 'turning point' and the imminent war between the USA and Russia, but they still did a bit nevertheless. They were hostile to the SS, which was still fighting. 'In the end they'll make a dash for it in civilian clothes and get away'.

From 5-18 May they stayed in the Amtshaus, 'Village Office', for the rest of their stay in Unterbernbach. During the move there they got into conversation with a woman from Berlin:

The woman, from north Berlin, ended up here a week before us by way of Silesia. She told us that she 'had heard from a sergeant that Fritzsche, a prisoner of the Russians, had announced on the radio': Hitler and Goebbels had shot themselves, the Russians were helping the Berliners to put out the fires, the war was completely over. […] But it was impossible to find out anything reliable, we have been without electricity and therefore cut off since Saturday, 28 April, that is, for one week.

Hans Georg Fritzsche, a propaganda minister, witnessed Hitler's death in the Berlin bunker. He was taken prisoner by the Russians on 1 May 1945.

As the defeat of Germany rolls over them, the villagers find out that none of them were Nazis. 'What is the truth, how can it be established, even approximately?' wrote Klemperer. Hitlerism, according to Flamensbeck now, had really only been un-Bavarian politics:

And ever more puzzling, despite Versailles, unemployment and deep-seated anti-Semitism, ever more puzzling to me, is how Hitlerism was able to prevail. Here – Flamensbeck is an example of this – they sometimes talk as if Hitlerism had been essentially a Prussian, militaristic, un-Catholic, un-Bavarian cause. But Munich, after all, was its Traditionsgau , its stamping ground. And how was this cause able to win over sceptical and socialist Berlin and maintain itself there?

In respect of religion, Flamensbeck says that the Party program had respected religion insofar as it did not encroach on politics. At the beginning he had not grasped the treacherousness of this treacherous word 'insofar'.

But Fräulein Haberl states that Flamensbeck had been a 'fanatical' National Socialist for a long time.

Yet more rumours in this time of uncertainty:

6 May: The latest rumour – someone is always 'said to have heard something on some radio somewhere: Germany has capitulated to Eisenhower, but is continuing to fight against Russia; Goebbels has shot himself and his family, Hitler has disappeared.

8 May: This is now the eleventh day without light (presumably it did not, after all, fall victim to a thunderstorm on 28 April, but to the fighting; the Steiner-Haberl sisters relate that on their cycle ride to Neuburg they saw wires down everywhere). No light – no radio and no news.

The greatest of our present anxieties and problems are related to that. Above all the question: When and how shall we be able to get away from here and get to Dresden? How on earth can we even get to Aichach? And what shall we find there?

9 May, Wednesday morning. Electric light and with it the radio are expected hourly. So far nothing. Heckenstaller, the mill owner here, has his own electricity supply. Yesterday he gave out as reliable radio news: Total capitulation with the surrender of all submarines and midget submarines was signed yesterday, 8 May, at three o'clock in the morning, on the German side by Admiral Dönitz. […] The many airplanes that passed over us yesterday in groups of three, very low and slow, are said to have been transports. Subjectively, from our point of view, the characteristic thing about them is that we no longer look for cover, are no longer afraid and yet with every airplane remember our past fear.

'Life goes on', even in the rubble of the greatest war the world had ever seen:

In the evening a woman came to Flamensbeck to register her children's milk ration card, young, not unintelligent. She appeared to be from Munich and had cycled there for a day recently.

The woman related with conviction and Flamensbeck undoubtedly believed her that America had issued an ultimatum to Russia to evacuate eastern Germany immediately. I asked the woman if she had heard anything about Hitler and the other Nazi bosses; no, she had had no time to ask about that, in other words: It no longer interested her. The Third Reich is already almost as good as forgotten, everyone was opposed to it, 'always' opposed to it; and people have the most absurd ideas about the future.

When the light came on again the day before yesterday, the word was that we must still continue to black out. That was cancelled yesterday, on 12 May 1945, meaning therefore, that we saw illuminated windows for the first time since 1 September 1939, almost six years ago. There are only a few windows in the village and yet the place immediately looked quite different. It made a great impression.

But now the great terrors have evaporated – bombs, discovery, persecution – Victor is faced with the all the irritants and deprivations which up to now had all been suppressed by the greater peril. We suddenly hear of things things he has not mentioned so far:

But what good is all the awareness of the perils we have come through – you may put on the light, you may watch the never-ending flyby without a care, there is no Gestapo for you to fear, you once again have the same rights no, probably more rights than those around you – what good is it all?

Irritants are more bothersome than the mortal struggle. The irritants are piling up now and our powers of resistance and patience are badly shaken. The terrible heat, the great plague of mosquitoes on top of that. The lack of anything to drink – now even the inn has run out of coffee. The lack of underwear, the unspeakable primitiveness of everything that has to do with eating: plate, bowl, cup, spoon, knife, partly (or mostly) completely absent, partly completely inadequate. In the long run (and in this heat) the distress caused by the inadequate way food is served at the Flamensbecks' – when the wife serves the food we don't even get a plate each – and the coarseness of preparation. Today for the first time I could hardly stomach the warm, flabby, almost raw bacon, the bland bread soup has tormented me for days.

Eva, for her part, suffers greatly from the lack of tobacco and unlike me she cannot drink water. I know it all sounds odd, you might even say: ungrateful, after everything we had to put up with so far; these are no more than everyday calamities. But as such they torment you tremendously. We are longing to get away from Unterbernbach.

After nearly a dozen years of tobacco deprivation Eva's addiction still grips her just as strongly. 'Now that the soldiers have gone' notes Victor, 'there are not even cigarette ends on the streets'.

The return to the rubble

The Klemperers now want nothing more than to go home. To this end, on 14 May, Victor makes the wearisome trip to Aichach to organize their return.

There was a fairly large crowd outside the Strasser shop, mostly foreign workers who are being sent away first, for the time being to assembly centres, and among them some Germans.

On the threshold of the shop was a civilian, in appearance like a Bavarian servant, with a white armband: 'Police'. But he really was a genuine Bavarian servant. To my question whether there was an interpreter inside and whether you could enter, he put a finger to his lips and replied, Nix is, 'Nothing's there'… There were more solid Bavarian policemen around; I asked another one and he said you could enter and join the queue. The first thing I saw beyond the head of the queue and the shop counter was a cloud of smoke [ …].

A young woman with large, grey-blue eyes, not Jewish-looking, with thickly applied lipstick (so thick that no deception was intended), chain smoking, talking animatedly in an Austrian dialect to the foreigners, to the Bavarians, to a male colleague, a female colleague, gesticulating vigorously, in her dealings concise and insistent but never discourteous; only repeating continually that there was no entry permit to Munich or anywhere else and very often emphasising: this and that would be solved by the civilian administration, but for the present the military government was here. […] The shop grew emptier and the pressure on the Viennese woman reduced.

The moment of truth had come for Victor:

I told her in a quiet voice and in a few words who I was and pushed my Jewish identity card towards her. Immediately smiling politeness, helpfulness, respectfulness. One 'Herr Professor' after the other. Did I need financial help, did I have decent accommodation, clothing would be attended to, tomorrow she would have the mayor of Unterbernbach there, she would make a note of my name: 'K-l-e-m-p-e-r-e-r', beaming: 'I've heard of it' – she will no doubt have heard of Georg or Otto Klemperer, nevertheless it was to my advantage. – 'I shall talk to the mayor, Herr Professor!' – 'Dear Madam, I really would not like people in the village to find out…' Dismissively: 'Well, do you think you still have anything to fear? On the contrary: You will get preferential treatment!' But you will still have to have patience with regard to your departure. But I had nothing at all to fear. 'Your house? But you will receive compensation … So, I trust, Professor, you may return to your post very soon!'

Victor had two famous relatives: his cousin Otto Klemperer (1885-1973), the conductor and composer, and his brother Georg Klemperer (1865-1946) a renowned doctor in Berlin. Both of them had the good sense to emigrate to the USA, Otto in 1933 and Georg in 1935. Victor had all kinds of reasons for not emigrating: they caused him twelve years of misery and humiliation and nearly cost him his life.

After a dozen years of status humiliation for Klemperer involving the loss of his post, of his titles and all other marks of respect, a dozen years of being treated like dirt, the pendulum swung to the other extreme within a few moments.

No other people in Europe have such a respect for academic and official titles as the Austrians: it was in the nature of the Austrian official to treat Professor Dr Klemperer with the utmost politeness. Not surprisingly for us, the sudden change, after all those years of denigration, came as quite a shock.

Then I stood outside completely astounded. Success or failure? For the time being there was no hope of departure and […] God knows what she will say to the mayor and in what light I would then appear to the village. On the other hand I had undoubtedly established friendly relations with the Military Government.

That evening in the schoolhouse I said that I no longer wanted to keep my cards close to my chest, explained and showed my Jewish identity card. 'We already suspected as much' – 'and we assumed that you had an idea of that, too'. The two of them (before her marriage Frau Steiner had also been a teacher) then related their links with Jews – friendship, 'among relatives', sympathy, political persuasion – from the Munich ghetto, from various cases in which Jews had 'died' and been resurrected with different names and documents and had so survived the Third Reich. It was a long and intimate evening.

The day after the high point in Aichach and the evening of warm friendship in the schoolhouse, the reality of their current situation comes back to them:

15 May, Tuesday, around two in the afternoon. […] Still no trains are running, still no chance of transport from here, still no coffee, no tobacco, no clothing, no possibility of movement, of newspapers, of getting or listening to news. Tomorrow is our 16 May. We shall be able to observe it with a lighter heart than in past years, but we cannot 'celebrate' it materialistically, with wine and roast and real coffee and tobacco, we cannot celebrate it yet.

The Klemperers had a civil wedding on 16 May 1906, hence 'our 16 May'. They had been married for 39 years.

The last days in Germany were also marked by events that proved that the Nazi Hydra still had dangerous heads. The sisters had related how a deserter living in the village, a family man, had gone to Aichach to do some shopping. He never returned. He had been hanged by the SS there. The letter he was allowed to write before his execution arrived a few days later. Pockets of Nazi resistance carried on with their murderous work despite the hopelessness of their cause.

The evening of their wedding anniversary they joined the sisters in the schoolhouse once more.

A long evening in the schoolhouse; […] we talked about our past, our plans: we became friends.

A sentence of an Allied declaration broadcast on Swiss radio shook and gripped me: Germany had 'ceased to exist as a sovereign state', but the Allies could not encumber themselves with its administration, Germans would have to do this task under Allied supervision.

I note here also what the sisters related from other radio reports: that in Aachen schools had already opened again, with pre-Nazi textbooks that had been 'found in an American library'; that in Frankfurt 140 Jews had been found still alive and had immediately been employed in the reconstruction effort. It was immediately clear to us both that I had to try to get involved, to register my claims and abilities.

Thus to the Klemperers' desire to get back home was now added Victor's new-found desire to get involved in the reconstruction of the new Germany. He could no longer just wait for the situation to normalise and a dependable railway service to begin running once more. He had to act now.

He and Eva decided to walk to Aichach the following morning, 17 May, and press his contacts in the Military Government to sanction his immediate return to Dresden. That evening he wrote:

17 May, Thursday: My hand is trembling from the march in the heat to and from Aichach. It took us from seven-thirty to ten-thirty to get there, followed by the struggle with officialdom, then Eva's fainting fit.

Complete success. The march back took us until now.

This is the end of the village episode and the beginning of our return home. Early tomorrow morning off to Munich.

We take our leave from Victor and Eva at this point in his diary. It was a great high point for them after so many years of struggle, humiliation and terror. We cannot blame them that, after so much deprivation, their hopes at that moment took flight. Austrian levels of feudal obsequiousness had led him to expect some sort of privileged transport to Dresden – perhaps even an aircraft!

Unfortunately and in hindsight quite predictably it was not to be like that. Millions of Germans, privileged and common, were on the move in an infrastructure that was largely rubble. Victor's privileged status had really only been simple Habsburg politeness, soaked up thirstily by a man who had endured a dozen years of humiliation and degradation.

'Hubris!', Victor wrote in his diary only a few days later, when Nemesis and the Furies, the couple's most loyal companions, had returned to blight them once more. In Aichach they had been treated like important persons; once on the journey back they became just two more among the millions of refugees trying to get home, all special privileges forgotten.