3 May 1810: Lord Byron and Lt. Ekenhead swim across the Hellespont

Richard Law, UTC 2018-05-01 06:34

On 3 May 1810 – 208 years ago for the numerically challenged – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) swam the Hellespont (now called the Dardanelles) between Sestos (now a pile of rubble near to the town of Eceabat in Grecian Gallipoli) and Abydos (now a pile of rubble near the town of Çanakkale in Turkey). That 3 May was a Thursday, as is this 3 May, so all the more reason for us to celebrate that remarkable event.

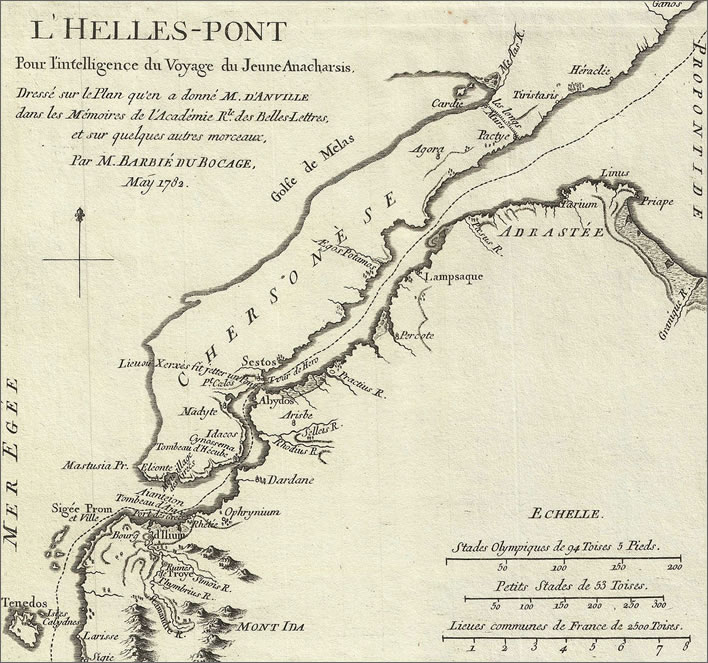

The Hellespont in a 1782 map by Jean Denis Barbie du Bocage (1760-1825). [Click to open a large image in a new tab.]

Byron, in the region on his first Mediterranean tour, was inspired to perform this feat by the legend of Hero and Leander.

Hero lived in a tower in Sestos, whereas Leander lived in Abydos on the other side. The tradition is that Hero was a 'priestess of Aphrodite'. For whatever reason, their passion had to be kept secret, so at night under cover of darkness Leander swam the Hellespont to receive the reward for his devotion – probably a nice cup of cocoa and a couple of Gypsy Creams. It may not have been every night – even Hellenic suitors have their limits – but only when Hero lit the lamp at the top of her tower did he know that a nightcap would be waiting for him.

The inhibiting effort of such a swim on poor old Leander struck the great fornicator Byron, too, as he noted in a letter after the fact to his friend Henry Drury:

This morning I swam from Sestos to Abydos, the immediate distance is not above a mile but the current renders it hazardous, so much so, that I doubt whether Leander's conjugal powers must not have been exhausted in his passage to Paradise.

Byron to Henry Drury, from the Salsette, off the Dardanelles, May 3rd 1810.

Those old enough to remember the 1960 pop hit Running Bear, the title of which was always good for a snigger in those more laced-up times, will get the idea.

Hero lit the lamp in her window to guide Leander across the passage. One stormy night, however, just when Leander most needed some guidance, the lamp blew out, he lost his way and was drowned.

William Etty (1787-1849), Hero, Having Thrown herself from the Tower at the Sight of Leander Drowned, Dies on his Body, 1829. Image: Tate.

Unenlightened male readers of this tale might try to point out the folly of leaving any technical device in the charge of a women. They will possibly also make much of the characteristic emotional female reaction that followed the inevitable failure: instead of improving the design of the lamp (as a man surely would) so that such tragedies did not happen in future, she responded emotionally and threw herself, her heart broken, into the waves, wherein she also perished. Consequently, the development of a reliable storm lamp would take even more time.

However, anyone who suggested such a thing on this website would earn a stern reproof for such shocking sexism.

The Divine Mind comprehends Hydrography, too

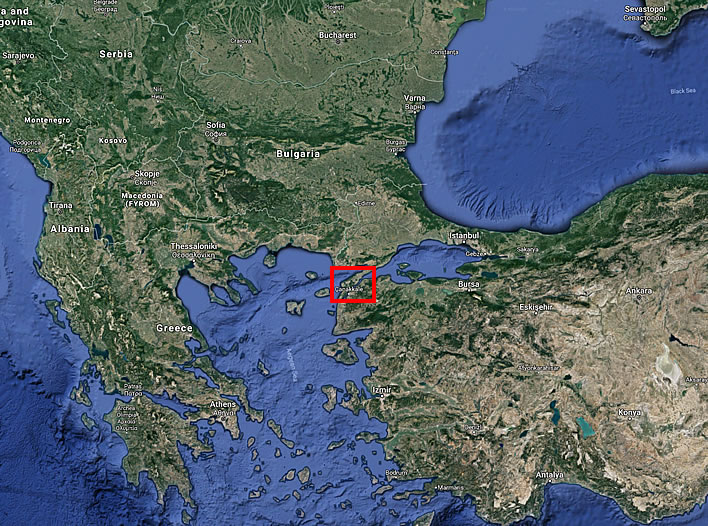

A Google Maps view of the region around the Hellespont (red rectangle).

The Hellespont is indeed a dangerous stretch of water. It is the narrow channel connecting the Mediterranean (more precisely, the Aegean Sea) with the Sea of Marmara and thence (through the Bosporus) with the Black Sea. At its narrowest point today it is about 1.5 km (~1 mile) across. It is not only narrow but also relatively shallow (around 70 metres), meaning that the currents are fast and erratic.

Currents? Yes, for there are, in fact, two currents, which flow simultaneously in opposite directions. The dominant current is the surface current arising from the drainage of the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea into the Aegean. This current flows at a speed of between three and five knots down the Hellespont. This current is so powerful that it can be felt right across the Aegean. The lesser current flows in the opposite direction along the bottom of the Hellespont.

In addition to the effects of the shearing at the interface of the two currents, the many small bays along both shores generate standing eddies. It gets worse: both currents are also affected by the Coriolis forces arising from the rotation of the Earth. The top, outflowing, current is forced slightly against the right bank, whereas the bottom, inflowing, current is forced slightly against the left bank. This effect, though generally weak, can lead to the currents having a greater effect on one bank than the other. In the Bosporus, much shallower and narrower than the Hellespont, with a much faster current in a much more north-south alignment, this effect can even bring the bottom current to the surface on one side.

A detail from the Hellespont map of Barbie du Bocage. It shows us Sestos, the Tour de Hero and Abydos. The region has a rich history: bottom left is the eighteenth-century guess at the position of the city of Troy, only a few kilometres away from the modern ruins, whose location was first accurately determined in 1822.

The ancients realised that a direct crossing of the narrowest part, at that time between the European Sestos and the Asiatic Abydos, was impossible – the currents were simply too strong. Instead the departure and landing points for the crossing were offset in order to make the best of the current in each direction.

From Abydos, boats (and Leander, wanting to get over to Hero up in her tower in Sestos, his cocoa getting cold) would leave from a point some way upstream. This point was marked with a tower. A departure from there would bring them along the diagonal to a landing point near Sestos. After that, traffic would need to go a short distance over land to get to Sestos itself. The landing point on that side was marked by a tower, which unsurprisingly came to be known as 'Hero's Tower'. It was an important aid to navigation across these rapid and fickle waters, assuming of course that the woman in charge has kept the light going.

The return route from Sestos for boats (and Leander, now refreshed or perhaps wearied by his nocturnal snack) was a little simpler. Departing from 'Hero's Tower', crossing traffic can take the diagonal from there direct into the harbour of Abydos. On this journey the tower near to Abydos was not needed – it was only ever the departure point. The tower also remained unnamed, despite all Leander's feats as a season ticket holder on the crossing.

Byron had a clear grasp of the vectorial facts of crossing such fast flowing water, as is clear to anyone reading his extended account of his feat in the Documents section below.

The winds in the area are also strong and extremely unpredictable: the sudden storm that did for Leander is a common occurrence, since fast currents and strong winds create rough waves on the surface. As if that weren't enough, at most times of the year the water is formidably cold – as Byron found out for himself, forcing him to break off his hasty first attempt:

The water was extremely cold, from the melting of the mountain snows. About three weeks before, in April, we had made an attempt; but having ridden all the way from the Troad the same morning, and the water being of an icy chillness, we found it necessary to postpone the completion till the frigate anchored below the castles...

From Byron's note to his poem Written after swimming from Sestos to Abydos.

A huge river network, which includes the Danube, drains into the Black Sea, which means that the meltwater of a good half of Europe ends up there.

His aquatic Lordship

At the time of his swim, Byron was almost in the middle a tour of the Mediterranean that would last two years. He left Britain on 2 July 1809 and visited Portugal, Spain, Gibraltar, Sardinia, Malta, Albania and Greece. He arrived at Athens on Christmas Day and stayed there until early March 1810. He ended up in Constantinople (Istanbul) in April, which was his base during his attempts on the Hellespont. After the successful swim on 3 May he zig-zagged around the region, spending his second Christmas in Athens. He finally returned to Britain on 14 July 1811.

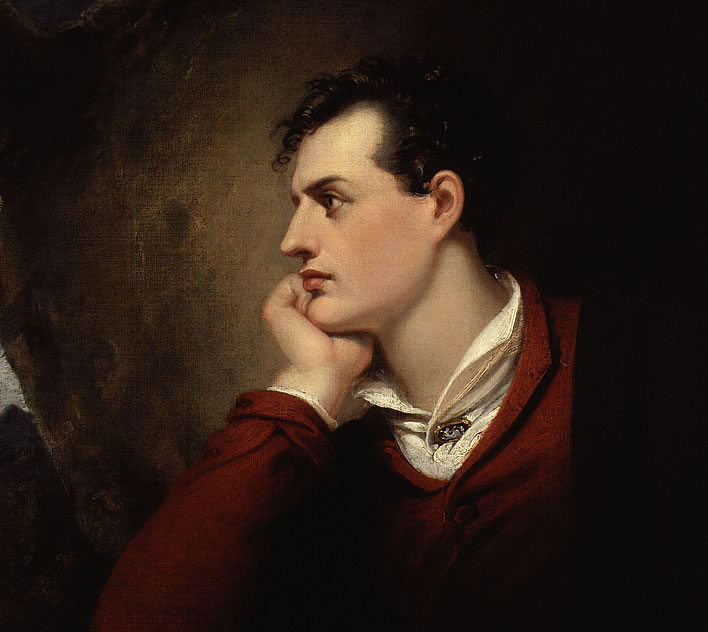

Richard Westall (1765-1836), George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, 1813. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

By 3 May 1810 the frigate Salsette had arrived in the Hellespont and Byron, accompanied by an accomplished swimmer from the Salsette's crew, Lieutenant Ekenhead, set off on his second attempt to repeat Leander's swim from Sestos to Abydos. It took Byron an hour and ten minutes to do the swim; Ekenhead was five minutes quicker. In the end nothing bad happened, but it was wise of both of them not to undertake such a swim in tricky conditions unaccompanied (a boat went along with them).

Although Lieutenant Ekenhead pipped him by five minutes on the crossing – a fact about which Byron was vague, if he even mentioned it at all – Byron's effort was just as noteworthy.

Byron, on dry land an ungainly mover as a result of his club foot, in the water was a passionate and strong swimmer. In our piece on Rupert Brooke's poem Grantchester we touched upon Byron's swimming in the context of Brooke's vision of the ghostly lord, who studied at Cambridge, swimming in the pond near Grantchester now called Byron's Pool.

Still in the dawnlit waters cool

His ghostly Lordship swims his pool,

And tries the strokes, essays the tricks,

Long learnt on Hellespont, or Styx.

Byron's dear friend Charles Skinner Matthews – some think him Byron's bitch – died in a swimming accident in the Cam on 2 August 1811, only a few weeks after Byron's return to England from his Mediterranean tour and Hellespont adventure. His friend Scrope Davies broke the bad news to Byron:

My dear Byron

Matthews is no more – He was drowned on Saturday last by an ineffectual attempt to swim through some weeds after he had been in the Cam 3 quarters of an hour – Had you or I been there Matthews had been alive – Hart saw him perish – but dared not venture to give him assistance Had you been there – Both or neither would have been drowned…

Scrope Berdmore Davies to Byron, from Limmer’s Hotel, Conduit Street London, August 5th or 6th 1811. Davies gives an incorrect day: Matthews drowned on Friday, not Saturday.

However, the last sentence, 'Both or neither would have been drowned', makes it clear that it was not just Byron's swimming skills that would have saved him but also his unhesitating courage.

In Byron's reply to Scrope Davies, the conqueror of the Hellespont reflects on life's ironies:

Some curse hangs over me and mine. My mother lies a corpse in this house; one of my best friends is drowned in a ditch.

Byron to Scrope Berdmore Davies, from Newstead Abbey, August 7th 1811.

Such feats as the swimming of the Hellespont contributed greatly to Byron's dashing reputation, known across Europe, so a poem about it was in order:

Written after swimming from Sestos to Abydos

If, in the month of dark December,

Leander, who was nightly wont

(What maid will not the tale remember?)

To cross thy stream, broad Hellespont!

If, when the wintry tempest roared,

He sped to Hero, nothing loth,

And thus of old thy current poured,

Fair Venus! how I pity both!

For me, degenerate modern wretch,

Though in the genial month of May,

My dripping limbs I faintly stretch,

And think I've done a feat to-day.

But since he crossed the rapid tide,

According to the doubtful story,

To woo,—and—Lord knows what beside,

And swam for Love, as I for Glory;

'Twere hard to say who fared the best:

Sad mortals! thus the Gods still plague you!

He lost his labour, I my jest:

For he was drowned, and I've the ague.

May 9, 1810. First published in Childe Harold, 1812.

He was justifiably proud of himself. He recounted his feat in letters to friends and to his mother. He also mentioned it as an aside in in his poem Don Juan, this time mentioning Lieutenant Ekenhead by name:

But in his native Stream, the Guadalquivir,

Juan to lave his youthful limbs was wont;

And having learnt to swim in that sweet River,

Had often turned the Art to some Account;

A better Swimmer you could scarce see Ever,

He could, perhaps, have passed the Hellespont,

As Once (a feat on which ourselves we prided)

Leander, Mr. Ekenhead, and I did.

Byron, Don Juan, 1819, Canto II, Stanza 105, ll. 833-840.

Don't try Hellespont swimming nowadays: you will end up sliced and diced by ships' screws in one of the busiest sea-lanes in the world. The swim is repeated annually these days, but at the end of August, on the Turkish National Day, when the water is a tad warmer and the marine traffic is held up for a couple of hours.

Documents

Here are some documents related to Byron's swim across the Hellespont, to save you having to go fishing in distant waters.

Byron's note to the poem

Byron added the following note to his poem Written after swimming from Sestos to Abydos, just in case readers might overlook his achievement. Some hold it against Byron that he did not include Ekenhead's name in the poem, but there are very good poetic reasons for not cluttering the work with an extraneous person. Ekenhead gets his due portion of credit in the note Byron appended to the poem:

On the 3rd of May, 1810, while the Salsette (Captain Bathurst) was lying in the Dardanelles, Lieutenant Ekenhead, of that frigate, and the writer of these rhymes, swam from the European shore to the Asiatic – by the by, from Abydos to Sestos would have been more correct.

The whole distance, from the place whence we started to our landing on the other side, including the length we were carried by the current, was computed by those on board the frigate at upwards of four English miles, though the actual breadth is barely one. The rapidity of the current is such that no boat can row directly across, and it may, in some measure, be estimated from the circumstance of the whole distance being accomplished by one of the parties in an hour and five, and by the other in an hour and ten minutes.

The water was extremely cold, from the melting of the mountain snows. About three weeks before, in April, we had made an attempt; but having ridden all the way from the Troad the same morning, and the water being of an icy chillness, we found it necessary to postpone the completion till the frigate anchored below the castles, when we swam the straits as just stated, entering a considerable way above the European, and landing below the Asiatic, fort.

[Le] Chevalier says that a young Jew swam the same distance for his mistress; and Olivier mentions its having been done by a Neapolitan; but our consul, Tarragona, remembered neither of these circumstances, and tried to dissuade us from the attempt. A number of the Salsette's crew were known to have accomplished a greater distance; and the only thing that surprised me was that, as doubts had been entertained of the truth of Leander's story, no traveller had ever endeavoured to ascertain its practicability.

'[B]y the by, from Abydos to Sestos would have been more correct': this confusing remark should probably be taken in the sense that the direction Abydos to Sestos would have been Leander's initial swim, as well as the direction of his fatal swim. Sestos to Abydos was the direction of his return swim.

Frederick Chamier

In his popular work The Life of a Sailor (1832), Frederick Chamier (1796-1870) gives us an eyewitness account of both of Byron's ventures on the Hellespont. Chamier had joined the Royal Navy frigate Salsette as a midshipman in 1809. He retired from the Navy in 1833 and became a popular nineteenth century writer. We make no claim for the accuracy of Chamier's accounts of Byron's Hellespont attempts, but there appears to be little reason for Chamier to have made anything up.

We took boat and repaired to Sestos, the strong fortification on the European side. It blew fresh, and the constant rains and easterly wind rendered the current stronger and the water colder than usual. I could not comprehend for what possible amusement we had crossed the Dardanelles, excepting it might have been to have visited apart of Europe and Asia in a quarter of an hour. The sea view of Abydos was not a likely reason, and we knew well enough that the jealous Turks who had refused us admission into the fortress on the Asiatic side, would be just about as uncivil on the European shore.

Whilst I was ruminating on the useless excursion, I saw Lord Byron in a state of nudity, rubbing himself over with oil, and taking to the water like a duck: his clothes were brought into the boat, and we were desired to keep near him; but not so near as to molest him. This was his first attempt at imitating Leander, of which he has made some remarks in the note to the lines written on crossing the Hellespont.

He complained instantly on plunging in of the coldness of the water; and he by no means relished the rippling which was caused by an eddy not far from where he started. He swam well – decidedly well. The current was strong, the water cold, the wind high, and the waves unpleasant. These were fearful odds to contend against, and when he arrived about half way across, he gave up the attempt, and was handed into the boat, and dressed. He did not appear the least fatigued, but looked as cold as charity, and as white as snow.

He was cruelly mortified at the failure, and did not speak one word until he arrived on shore. His look was that of an angry, disappointed girl, and his upper lip curled, like that of a passionate woman's :——I see it now, as if it were but yesterday.

[…]

The next day [3 May] was calm and warm. We had not a breath of wind, 'and ocean slumbered like an unweaned child.' Lord Byron was up early, and made arrangements for his second and more successful attempt at swimming the Hellespont. Mr. Ekenhead proposed to dispute the honour, and both gentlemen left the ship about nine o'clock, and landed on the European side.

Above Sestos there is a narrow point of land which juts into the Dardanelles, and below Abydos there is a similar formation of coast, the point of the sandy bay on the Asiatic side projecting some distance. From point to point, that is, if they were opposite to each other, the distance would be about a mile — certainly not more; but as the current is rapid, and it is impossible to swim directly across, the distance actually passed over would be between four or five miles.

Mr. Ekenhead took the lead, and kept it the whole way. He was much the best swimmer of the two, and by far the more powerful man. He accomplished his task, according to Lord Byron's account, in an hour and five minutes. I timed him at one hour and ten minutes, and his lordship at one hour and a quarter. Both were fresh, and free from fatigue; especially Ekenhead, who did not leave the water until Lord Byron arrived.

As the distance has been much exaggerated, our great enemy, Time, may be the best way of computing it. It is a well-known fact that it must be a strong swimmer to accomplish a mile an hour. I have often seen it tried, and tried it myself. A mile an hour is a very fair estimation; and therefore, making allowance for the time lost in floating, of which resource both availed themselves, the distance actually swam may be safely called a mile, and not more, certainly. This is no very Herculean task. The particular circumstance under which Leander undertook his nightly labour, if ever he did undertake it continually, which I am sceptical enough to doubt, makes the story palatable.

[…]

Poor Ekenhead did not live long to enjoy his triumph, or the pleasure of hearing his feats immortalised by the pen of Byron. On our return to Malta, he heard of his promotion to the rank of captain of marines; a rank not attained without many a dreary year's hard service; and having offered, it is supposed, an unusual libation to Bacchus on his good fortune having arrived, owing to his comrade's death, he somehow or other managed to tumble over the bridge which separates Nix Mangiare Stairs from Valetta, and was killed on the spot.

The Royal Marine Listings confirm that Captain Richard Ekenhead, serving on HMS Salsette, died on 7 April 1812 'due to a fall from the bastions'. The Nix Mangiare Stairs is the name of a narrow staircase with shallow steps that takes pedestrians from the harbour up to the Maltese capital of Valletta. The path then entered Valletta through the Marina Gate (a.k.a Del Monte Gate) over a short bridge that crossed a deep dry-moat. The gate was demolished in 1884 and replaced with the Victoria Gate.

Byron contra Turner

On 21 February 1821 Byron wrote from Ravenna to his publisher John Murray, marking the letter 'for publication'. The letter was a response to a criticism of him in William Turner's 1820 book Journal of a Tour in the Levant, that had been published by Murray. Byron responded vigorously to Turner's criticism:

In the forty-fourth page, volume first, of Turner's Travels (which you lately sent me), it is stated that 'Lord Byron, when he expressed such confidence of its practicability, seems to have forgotten that Leander swam both ways, with and against the tide; whereas he (Lord Byron) only performed the easiest part of the task by swimming with it from Europe to Asia.'

I certainly could not have forgotten, what is known to every schoolboy, that Leander crossed in the night and returned towards the morning. My object was, to ascertain that the Hellespont could be crossed at all by swimming, and in this Mr. Ekenhead and myself both succeeded, one in an hour and ten minutes, and the other in one hour and five minutes. The tide was not in our favour; on the contrary, the great difficulty was to bear up against the current, which, so far from helping us into the Asiatic side, set us down right towards the Archipelago.

Neither Mr. Ekenhead, myself, nor, I will venture to add, any person on board the frigate, from Captain Bathurst downwards, had any notion of a difference of the current on the Asiatic side, of which Mr. Turner speaks. I never heard of it till this moment, or I would have taken the other course.

Lieutenant Ekenhead's sole motive, and mine also, for setting out from the European side was, that the little cape above Sestos was a more prominent starting place, and the frigate, which lay below, close under the Asiatic castle, formed a better point of view for us to swim towards; and, in fact, we landed immediately below it.

Mr. Turner says, 'Whatever is thrown into the stream on this part of the European bank must arrive at the Asiatic shore.' This is so far from being the case, that it must arrive in the Archipelago, if left to the current, although a strong wind in the Asiatic direction might have such an effect occasionally.

Mr. Turner attempted the passage from the Asiatic side, and failed: 'After five-and-twenty minutes, in which he did not advance a hundred yards, he gave it up from complete exhaustion.' This is very possible, and might have occurred to him just as readily on the European side. He should have set out a couple of miles higher, and could then have come out below the European castle. I particularly stated, and Mr. Hobhouse has done so also, that we were obliged to make the real passage of one mile extend to between three and four, owing to the force of the stream.

I can assure Mr. Turner, that his success would have given me great pleasure, as it would have added one more instance to the proofs of the probability. It is not quite fair in him to infer, that because he failed, Leander could not succeed. There are still four instances on record: a Neapolitan, a young Jew, Mr. Ekenhead, and myself; the two last done in the presence of hundreds of English witnesses.

With regard to the difference of the current, I perceived none; it is favourable to the swimmer on neither side, but may be stemmed by plunging into the sea, a considerable way above the opposite point of the coast which the swimmer wishes to make, but still bearing up against it; it is strong, but if you calculate well, you may reach land.

My own experience and that of others bids me pronounce the passage of Leander perfectly practicable. Any young man, in good and tolerable skill in swimming, might succeed in it from either side.

[…]

With this experience in swimming at different periods of life, not only upon the spot, but elsewhere, of various persons, what is there to make me doubt that Leander's exploit was perfectly practicable? If three individuals did more than the passage of the Hellespont, why should he have done less?

But Mr. Turner failed, and, naturally seeking a plausible reason for his failure, lays the blame on the Asiatic side of the strait. He tried to swim directly across, instead of going higher up to take the vantage: he might as well have tried to fly over Mount Athos.

That a young Greek of the heroic times, in love, and with his limbs in full vigour, might have succeeded in such an attempt is neither wonderful nor doubtful. Whether he attempted it or not is another question, because he might have had a small boat to save him the trouble.

I am yours very truly,

Byron.

P. S. — Mr. Turner says that the swimming from Europe to Asia was 'the easiest part of the task.' I doubt whether Leander found it so, as it was the return; however, he had several hours between the intervals. The argument of Mr. Turner, 'that higher up or lower down, the strait widens so considerably that he would save little labour by his starting,' is only good for indifferent swimmers; a man of any practice or skill will always consider the distance less than the strength of the stream.

If Ekenhead and myself had thought of crossing at the narrowest point, instead of going up to the Cape above it, we should have been swept down to Tenedos. The strait, however, is not so extremely wide, even where it broadens above and below the forts. As the frigate was stationed some time in the Dardanelles waiting for the firman, I bathed often in the strait subsequently to our traject, and generally on the Asiatic side, without perceiving the greater strength of the opposite stream by which the diplomatic traveller palliates his own failure.

Our amusement in the small bay which opens immediately below the Asiatic fort was to dive for the land tortoises, which we flung in on purpose, as they amphibiously crawled along the bottom. This does not argue any greater violence of current than on the European shore.

With regard to the modest insinuation that we chose the European side as 'easier,' I appeal to Mr. Hobhouse and Captain Bathurst if it be true or no (poor Ekenhead being since dead). Had we been aware of any such difference of current as is asserted, we would at least have proved it, and were not likely to have given it up in the twenty-five minutes of Mr. Turner's own experiment.

The secret of all this is, that Mr. Turner failed, and that we succeeded; and he is consequently disappointed, and seems not unwilling to overshadow whatever little merit there might be in our success. Why did he not try the European side? If he had succeeded there, after failing on the Asiatic, his plea would have been more graceful and gracious. Mr. Turner may find what fault he pleases with my poetry, or my politics; but I recommend him to leave aquatic reflections till he is able to swim 'five-and-twenty minutes' without being 'exhausted,' though I believe he is the first modern Tory who ever swam 'against the stream' for half the time.

Turner's reply to Byron's protest was tardy – Byron had died in the meantime – and is not very interesting. It was appended to Murray's single volume edition of Byron's Life, Letters and Journals but only serves to confirm Turner's incomprehension of crossing the fast currents of the Hellespont in both directions.

Some naval maths

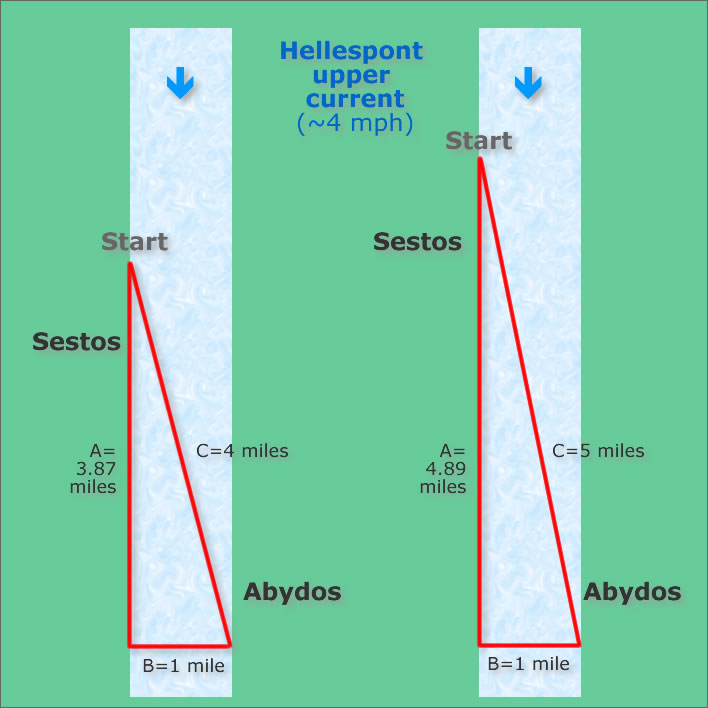

©Figures of Speech, link if reused.

If anyone can do basic trigonometry and master Pythagoras' Theorem, then it is the stout hearts of the British Royal Navy. Both Lord Byron and Midshipman Chamier had a similar view of the trigonometry of the situation.

The distance of 4 to 5 miles given by the naval types is the distance the swimmers travelled relative to fixed ground. It is the result of vectorial combination of the speed of the current and the speed of the swimmers in relation to the current. These distances are the hypotenuses (C) in our diagram.

Using Pythagoras' Theorem just as they did, we can deduce the values they used for the upstream distances:

- If the direct distance across the Hellespont (B) were 1 mile and the length of the hypotenuse (C), say, 4 miles, then the swimmers' starting points would have been 3.87 miles upstream (A) from their arrival point.

- Similarly, if the length of the hypotenuse (C) were 5 miles the distance upstream (A) would have been 4.89 miles.

The hydrographers tell us that the upper current flow in the Hellespont is between 3 and 5 knots, that is, 3.45 mph and 5.75 mph. Since the two swimmers were in the water for just over an hour they would have floated between 3.45 and 5.75 miles in that hour.

These two figures are in rough agreement with our figures for the upstream distances (A) derived from the naval calculations. Furthermore, they would have swum, according to Chamier's assertion of a swimming speed of 1 mph, about a mile, which is in rough agreement with the vector of the direct distance (B).

The overwhelming speed of the current (~4-6 mph) compared to the speed of the swimmer (~1 mph) is made manifest by the elongated form of the triangles in our diagram. No one could swim directly against such a current.

All these numbers are guesstimates and do not deserve their decimal points. We are also neglecting the vector arising from the conscious effort of swimming towards a landing point downstream. Nevertheless, we can say that the Navy's numbers do align with what the modern hydrographer knows about the current speeds, which in turn means that a starting point would have lain between 4 and 5 miles upstream from Abydos (A).

Faced with the task of determining the absolute positions of the start and end points of Byron's swim we must capitulate: since 1810 the banks of the Hellespont have changed appreciably and Sestos and Abydos have changed their locations, too. There is thus no point even trying to plot these points on a modern map. Older maps are too inaccurate for this purpose.

All we know is that Chamier is clear that the swim started above (the then) Sestos and ended below (the then) Abydos:

Above Sestos there is a narrow point of land which juts into the Dardanelles, and below Abydos there is a similar formation of coast, the point of the sandy bay on the Asiatic side projecting some distance.

Byron too, in his response to Turner, is also quite specific on this point:

[…] that the little cape above Sestos was a more prominent starting place, and the frigate, which lay below, close under the Asiatic castle, formed a better point of view for us to swim towards; and, in fact, we landed immediately below it.

And with that we can leave the consideration of that hour of swimming, which gave Byron his glory and his ague, to 2110 and those who will come after us.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!