20 June 1914: blasting and blessing

Posted by Richard on UTC 2018-06-18 17:33

The frenzy before the storm

The reader might ask, given the horrors of the cataclysm that would break over Europe on 3 August 1914 and the four years of carnage that would follow it, why we are going to write about the ultimately trivial artistic events of the few months leading up to that moment.

'Artists', the American poet Ezra Pound (1885-1972) stated on numerous occasions, 'are the antennae of the race'. If this is true we might expect some connection between the artistic activity and the broader history of the period.

Superficially at least, the frantic behaviour of artists in the years immediately before the Great War supports Pound's thesis. In Germany, many poets and writers were longing for something to happen – anything, just to put an end to the oppressive air of the storm that was coming and which everyone felt. But let's leave the Germans to one side for now.

Rage for the machine

In the equally febrile atmosphere of Italy, the Futurist movement had been founded in 1909. The movement glorified the machine and everything associated with it: speed, noise, violence, danger. Painting and sculpture received a new dimension: movement.

Would like nice in one's living room. Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space 1913. Image: MOMA.

For the Futurists, the representation of movement, in fact, became more important than the representation of static form. Their greatest propagandist, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's (1876-1944) fourth principle from his Futurist Manifesto of 1909 says as much:

4 We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose bonnet is adorned with great pipes, like serpents from its explosive breath – a roaring car that seems to ride on machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

4. Noi affermiamo che la magnificenza del mondo si è arricchita di una bellezza nuova: la bellezza della velocità. Un automobile da corsa col suo cofano adorno di grossi tubi simili a serpenti dall’alito esplosivo.... un automobile ruggente, che sembra correre sulla mitraglia, è più bello della

Vittoria di Samotracia.

F.T. Marinetti, 'Manifesto dei futurismo' Fondazione e Manifesto del futurismo Pubblicato dal 'Figaro' di Parigi il 20 Febbraio 1909. Online.

Here are some examples of what the Futurists were at:

Reminiscent of my first car, an ancient Austin Hereford, which also often dismantled itself once it was (reluctantly) underway. Giacomo Balla Speeding Automobile 1912. Image: MOMA.

Giacomo Balla Swifts: Paths of Movement + Dynamic Sequences 1913. Image: MOMA.

Umberto Boccioni Dynamism of a Football Player 1913. Image: MOMA.

Showing the later cubist influence. Ivo Pannaggi Speeding Train (Treno in corsa) 1922. Image: Fondazione Cassa di risparmio della Provincia di Macerata.

The machines they loved so much would become the main actors in the coming war. Germany had shown in the 1870 Franco-Prussian war that wars were won by industrial might – by machines, in other words. The winner was not the side with the biggest army but the side with the biggest guns and with the biggest bombs, with the best aircraft, the best transport and with the best tanks. The one that could hammer the most steel into shape.

The men were only there to be minced up by the machines – and it didn't really matter whether there was one hundred or one hundred thousand of them: grist to the mill, as we say.

The love affair with monstrous machines was just one aspect of the quite fundamental irrationality of the Futurists. It is thus a seductive idea that the lunacy of the Futurists was merely a precursor to that even greater irrationality of the Great War.

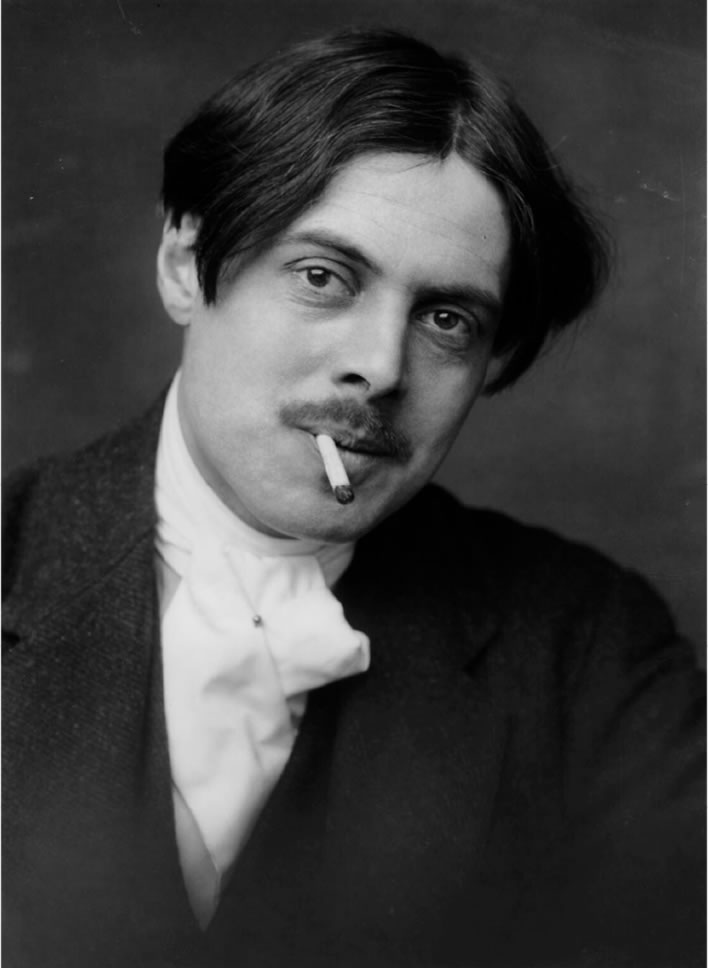

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, ND. Image: creator unknown.

Elevating irrationality to a guiding principle, Marinetti and the Futurists even wanted to destroy syntax, thus removing the basis of millennia of reasoning. In May 1913 Marinetti published an essay Distruzione della sintassi. Immaginazione senza fili. Parole in libertà, usually known in English as 'Destruction of Syntax. Imagination without Strings. Words-in-Freedom'.

The essay is quite bonkers. Unsurprisingly, it has never received a careful translation into English. A flavour will suffice:

My revolution is directed against the so-called typographical harmony of the page, which is contrary to the flow and ebb, the jumps and bursts of style that run through the page itself. For that reason we will use on the same page three or four different colors of ink and as many as twenty different typfaces if necessary. For example: italics for a series of similar or swift sensations, a bold, ronded face for violent onomatopoeia etc. With this typographical revolution and the multicoloured variety in the letters I propose to double the expressive force of words.

La mia rivoluzione è diretta contro la così detta armonia tipografica della pagina, che è contraria al flusso e riflusso, ai sobbalzi e agli scoppi dello stile che scorre nella pagina stessa. Noi useremo perciò in una medesima pagina, tre quattro colori diversi d'inchiostro, e anche 20 caratteri tipografici diversi, se occorra. Per esempio:corsivo per una serie di sensazioni simili o veloci, grassetto tondo per le onomatopee violente, ecc. Con questa rivoluzione tipografica e questa varietà multicolore di caratteri io mi propongo di raddoppiare la forza espressiva delle parole.

F.T. Marinetti, 'RIVOLUZIONE TIPOGRAFICA' in Distruzione della sintassi etc. 11 Maggio 1913. Online.

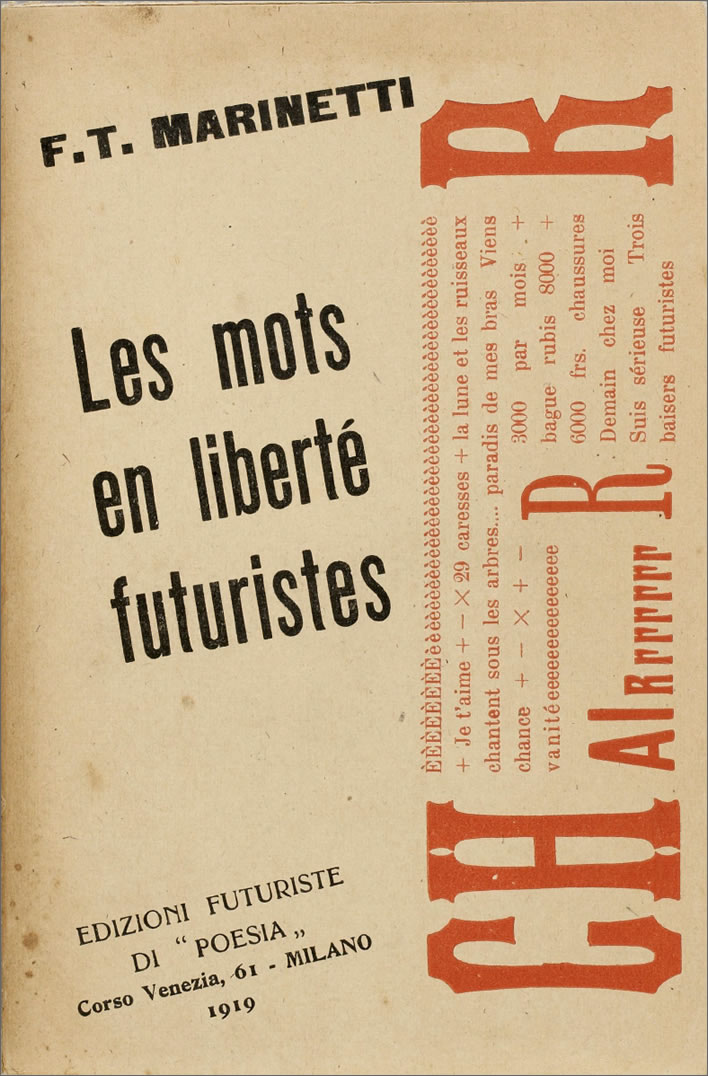

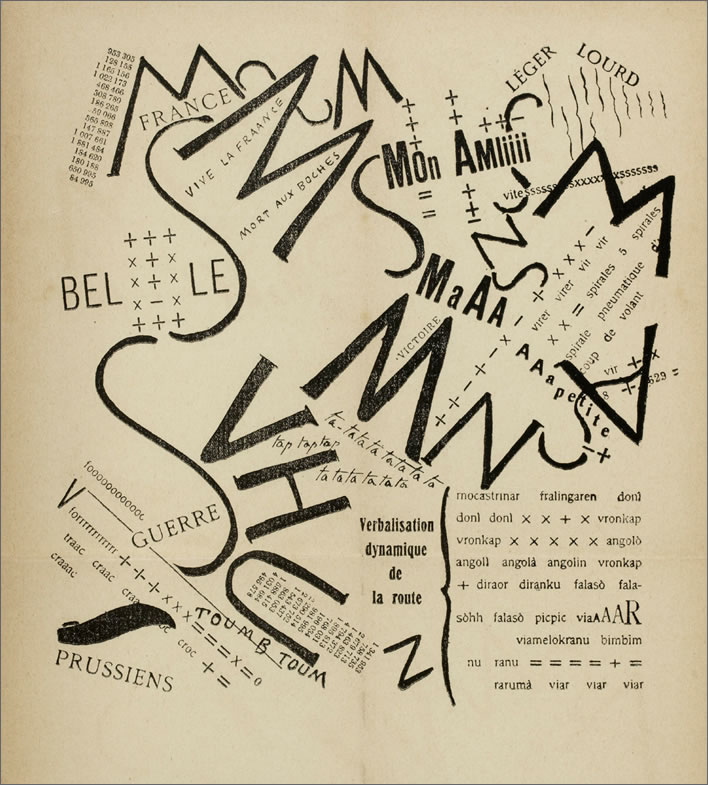

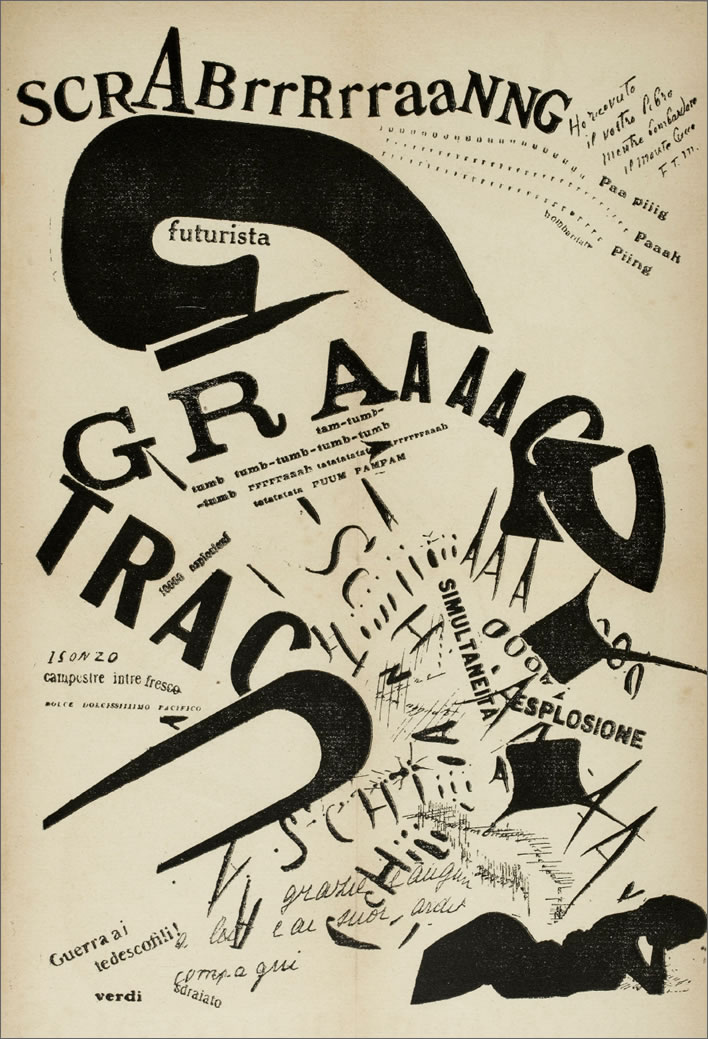

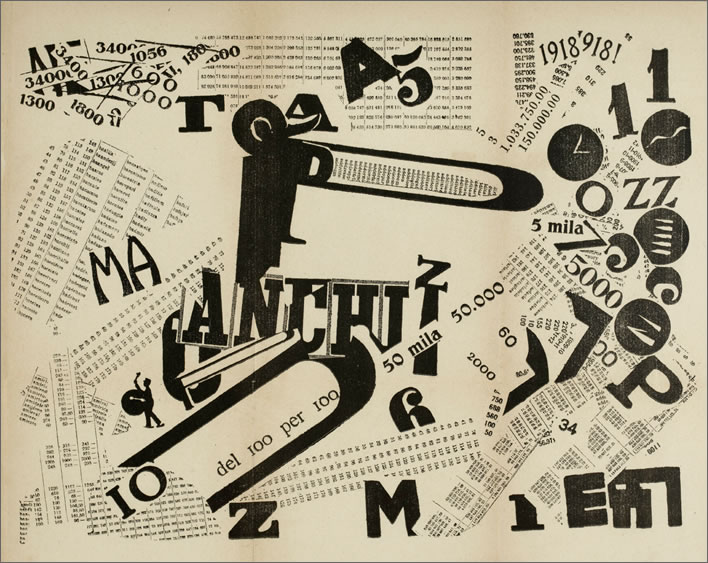

In 1919 Marinetti published a booklet containing a reworked and extended version of his 1913 essay, including some fold out illustrations of his ideas, Les mots en liberté futuristes, 'Futurist Words in Freedom', Milano: Edizioni futuriste di 'Poesia', 1919. Here are a few of Marinetti's examples of liberated words:

1. The cover of the booklet, with, embedded in it, Marinetti's design: Lettre d'une jolie femme à un monsieur passéiste, 'Letter from a pretty woman to a passé-iste gentleman'.

2. Après la Marne, Joffre visita le front en auto, 'After the [battle of] the Marne, Joffre visited the front by car'.

3. Le soir, couchée dans son lit, Elle relisait la lettre de son artilleur au front, 'That evening, resting on her bed, She re-read the letter of her artilleryman at the front'.

4. Une assemblée tumultueuse (sensibilité numérique), 'A tumultuous assembly (numeric sensibility)'.

It's interesting to note that in the back of this booklet there is a list of publications in the 'Poesia' series. There are 38 in all, 13 of which are marked Épuisé, sold out. We may consider the movement deranged, but it was clearly popular derangement.

Of course, in order to explain his concepts of the destruction of syntax etc., Marinetti is forced to use boring old lines of monotone type. Without his – albeit cryptic – comments on his example illustrations, his reader would be completely lost.

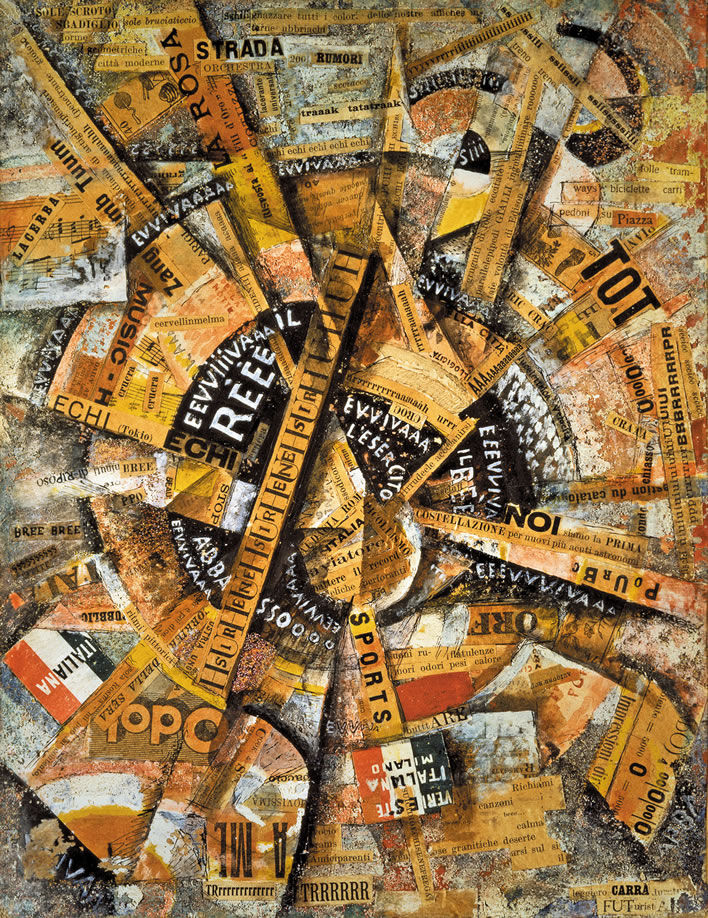

Carlo Carrà, Manifestazione Interventista (Interventionist Manifestation), 1914. Image: ©2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Just as German artists were longing for some violent resolution, the Italian Futurists elevated war to the status of some much needed cleansing. At the wheel of their devilish machine, they floored the pedal. Principle 9 of Marinetti's Manifesto:

9 We want to glorify war – the world's only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of libertarians, beautiful ideas for which one dies and the contempt for the feminine.

9. Noi vogliamo glorificare la guerra – sola igiene del mondo – il militarismo, il patriottismo, il gesto distruttore dei libertarî, le belle idee per cui si muore e il disprezzo della donna.

F.T. Marinetti, 'Manifesto dei futurismo' op. cit.

It appears, though, that when the Futurists spoke about war, they envisaged a nice, clean, mechanical war without the messy remains of any humans who happened to get in the way:

Not a drop of blood in sight: Gino Severini Visual Synthesis of the Idea of War 1914. Image: MOMA.

The British counterattack

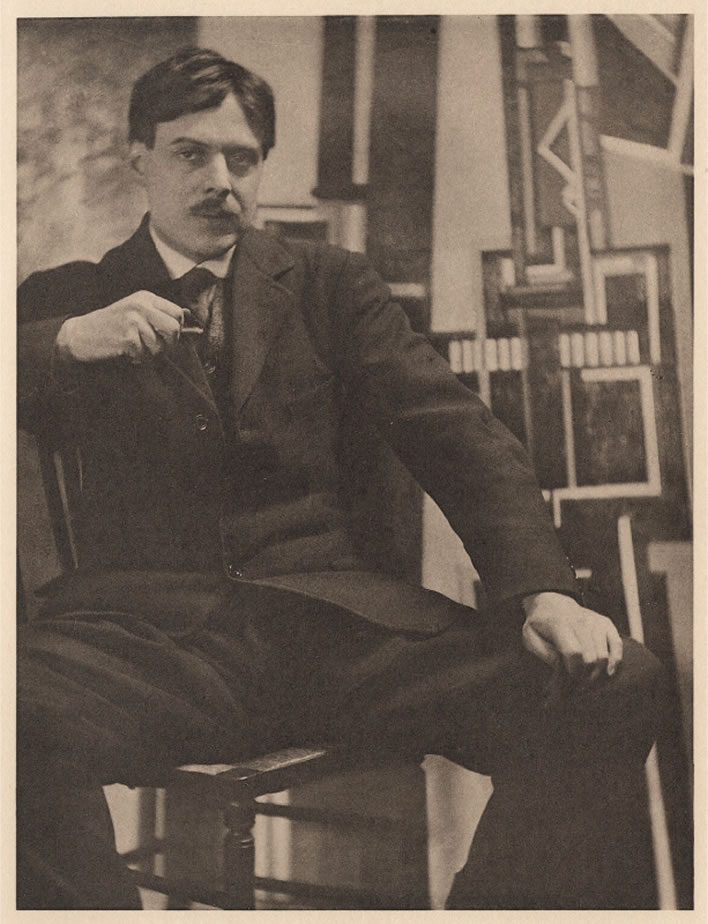

Wyndham Lewis by George Charles Beresford in 1913, around the time of Blast I. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG x6535

Britain had about three years of Marinetti and his Futurist poltergeists, until around the beginning of 1914 the writer and painter Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) set an artistic counterattack in motion:

Meanwhile the excitement was intense. Putsches took place every month or so. Marinetti for instance. You may have heard of him! It was he who put Mussolini up to Fascism. Mussolini admits it. They ran neck and neck for a bit, but Mussolini was the better politician. Well, Marinetti brought off a Futurist Putsch about this time.

It started in Bond Street. I counter-putsched. I assembled in Greek Street a determined band of miscellaneous anti-futurists. Mr. Epstein was there; Gaudier Brzeska, T. E. Hulme, Edward Wadsworth and a cousin of his called Wallace, who was very muscular and forcible, according to my eminent colleague, and he rolled up very silent and grim. There were about ten of us. After a hearty meal we shuffled bellicosely round to the Dore Gallery.

Marinetti had entrenched himself upon a high lecture platform, and he put down a tremendous barrage in French as we entered. Gaudier went into action at once. He was very good at the parlez-vous, in fact he was a Frenchman. He was sniping him without intermission, standing up in his place in the audience all the while. The remainder of our party maintained a confused uproar.

Lewis, Wyndham. Blasting & Bombardiering, London, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937. p. 33.

Marinetti in uniform in 1917. Image: photographer unknown.

Lewis' attack on Marinetti and Futurism took on physical form with the publication of the magazine Blast. It started as a means of distinguishing the new British artists who had gathered around Lewis from Marinetti's noisy supporters. Lewis recounts – presumably with some embroidery – an encounter with Marinetti in the Gentlemen's toilets:

'You are a futurist, Lewis!' he shouted at me one day, as we were passing into a lavabo together, where he wanted to wash after a lecture where he had drenched himself in sweat.

'No,' I said.

'Why don't you announce that you are a futurist!' he asked me squarely.

'Because I am not one,' I answered, just as pointblank and to the point.

'Yes. But what's it matter!' said he with great impatience.

'It's most important,' I replied rather coldly.

'Not at all!' said he. 'Futurism is good. It is all right.'

'Not too bad,' said I. 'It has its points. But you Wops insist too much on the Machine. You're always on about these driving-belts, you are always exploding about internal combustion. We've had machines here in England for a donkey's years. They're no novelty to us.'

'You have never understood your machines! You have never known the ivresse of travelling at a kilometre a minute. Have you ever travelled at a kilometre a minute?'

'Never.' I shook my head energetically. 'Never. I loathe anything that goes too quickly. If it goes too quickly, it is not there.'

'It is not there!' he thundered for this had touched him on the raw. 'It is only when it goes quickly that it is there!'

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 34. Ivresse, exhilaration, intoxication.

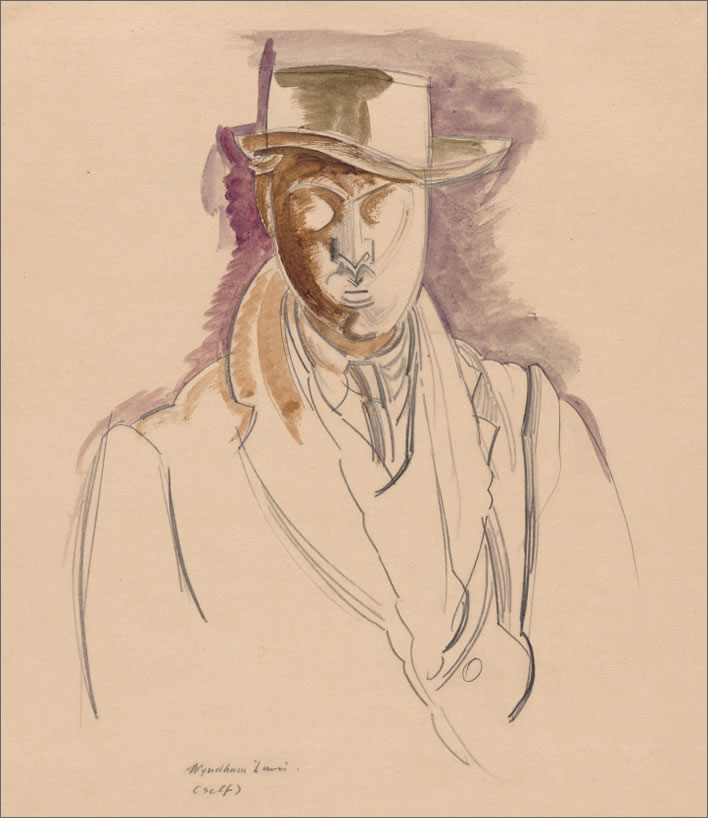

Wyndham Lewis Self-Portrait 1920. Image: MOMA.

Lewis tells us that he assumed the mantle of the new group's leader with easy grace:

And then I assumed too that artists always formed militant groups. I supposed they had to do this, seeing how 'bourgeois' all Publics were – or all Publics of which I had any experience. And I concluded that as a matter of course some romantic figure must always emerge, to captain the 'group'. Like myself! How otherwise could a 'group' get about, and above all talk. For it had to have a mouthpiece didn't it? I was so little of a communist that it never occurred to me that left to itself a group might express itself in chorus. The 'leadership' principle, you will observe, was in my bones.

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 32.

Lewis would also see Blast not just as a reaction to Marinetti but just as much a reaction to the staid, official forms of British culture of the time.

The periodical, Blast… was, as its name implies, destructive in intention.

What it aimed at destroying in England – the 'academic' of the Royal Academy tradition – is now completely defunct. The freedom of expression, principally in the graphic and plastic arts, desired by it, is now attained, and can be indulged in by anybody who has the considerable private means required to be an 'artist.' So its object has been achieved. Though it is only about twelve years since that mass of propaganda was launched, in turning over the pages of Blast to-day it is hard to realize the bulk of the traditional resistance that its bulk was invented to overpower. How cowed these forces are to-day, or how transformed!

Lewis, Wyndham. Time and Western Man, London, Chatto and Windus, 1927. p. 54f.

It was Ezra Pound who invented the name 'Vorticist' for the group behind Blast and who wrote of the creative Vortex that can arise when artists band together. Pound's talent for noise-making and uproar and publicity became the great motor behind the magazine.

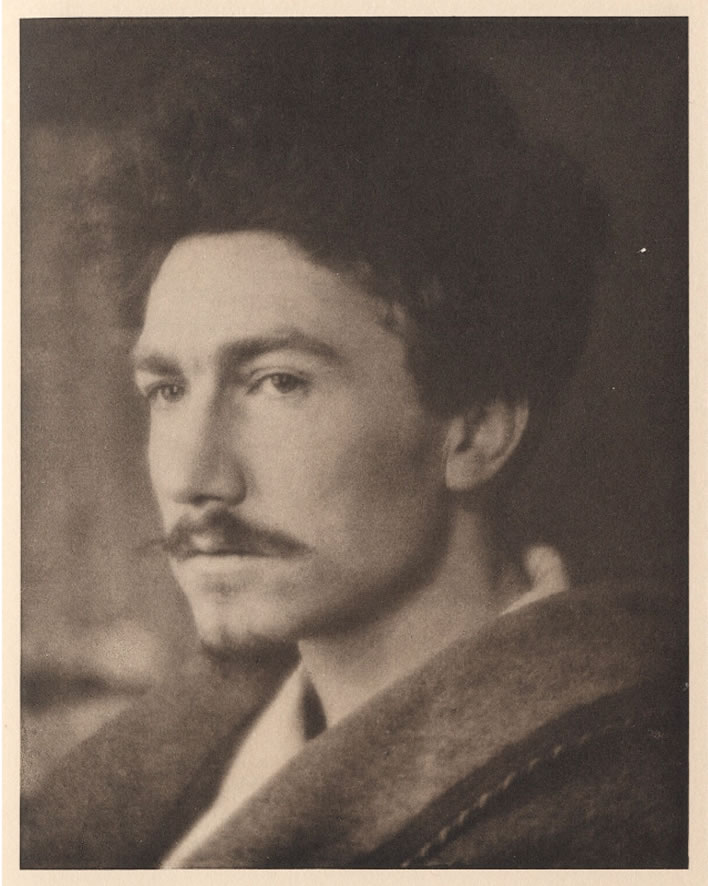

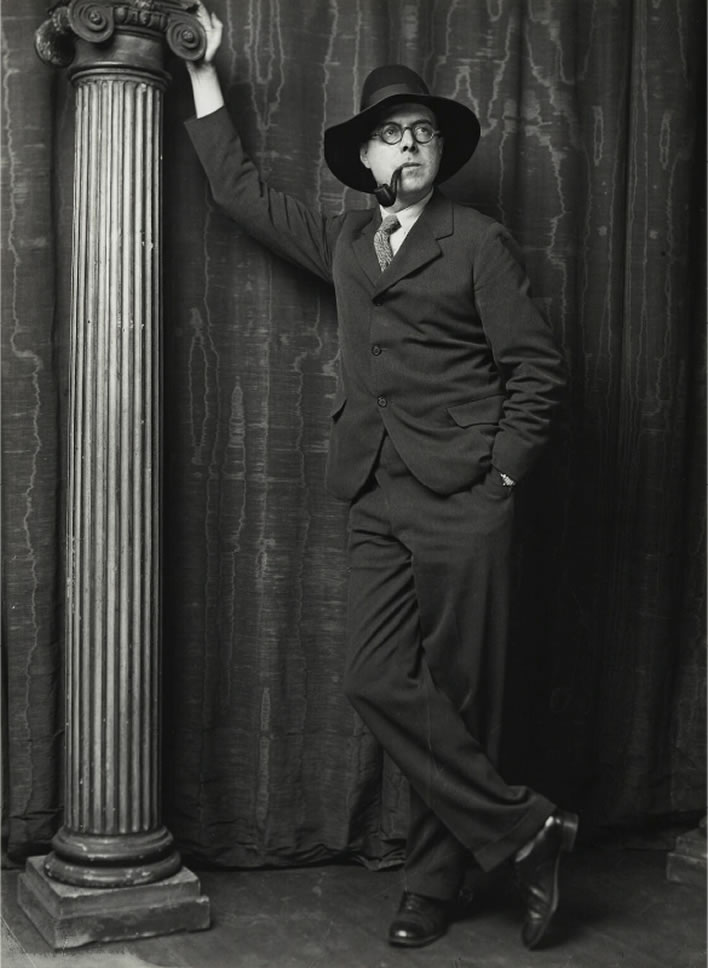

Ezra Pound photographed by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 22 October 1913, showing – as always – his grumpy side. He was eight days short of his 28th birthday at the time of the photograph. Image: ©The Universal Order / National Portrait Gallery London. NPG Ax7811

Around 1 April 1914 Pound announced his participation in the Blast project in a letter to James Joyce. At this stage the term Vortex was not mentioned:

NEW ADDRESS

[c. 1 April] 1914

5, Holland Place Chambers, Kensington. W.Lewis is starting a new Futurist, Cubist, Imagiste Quarterly, I think he might take some of your essays, I cant tell, it is mostly a painters magazine with me to do the poems. He likes the novel but isn't very keen on the stories. AND he cant pay. Still there'll be a certain amount of attention focused on the paper for a few numbers anyhow and it might be a good place to have your name.

Pound, Ezra, James Joyce, ed. Forrest Read. The Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, with Pound's Essays on Joyce, Faber and Faber, London, 1967. p. 26.

Alvin Langdon Coburn Vortograph of Ezra Pound 1916–17. Pound himself invented the term 'vortograph' to describe Coburns photographic experiments. Image: MOMA.

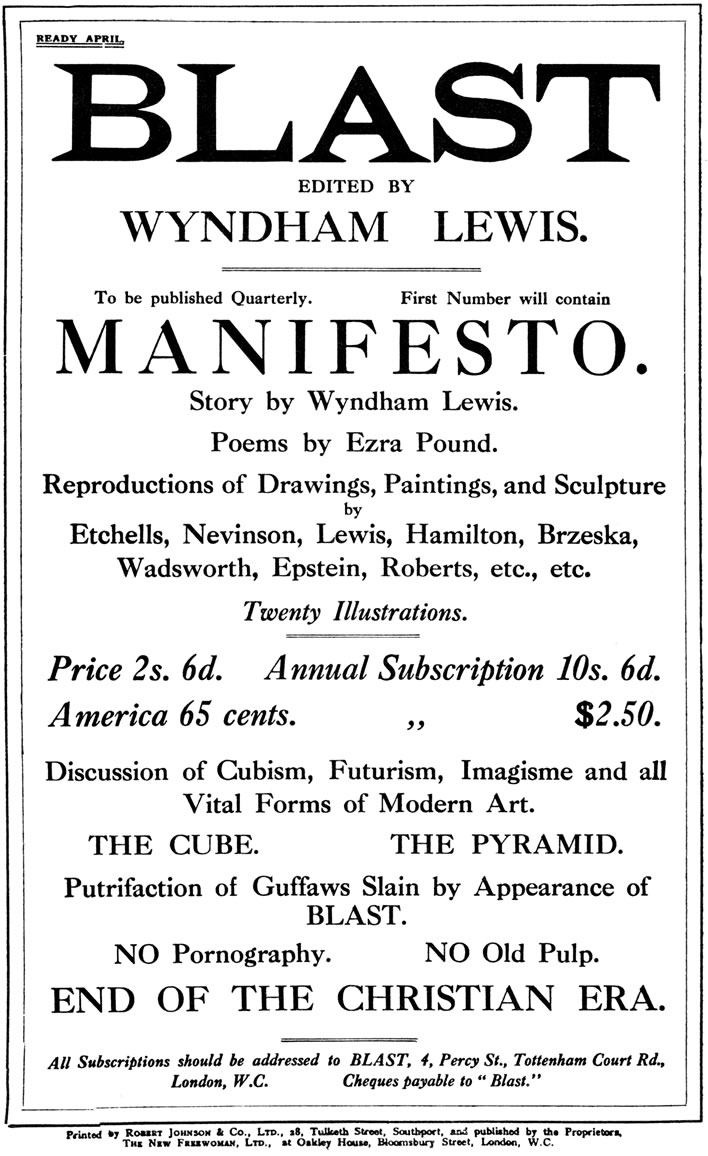

Also on 1 April the first advertisement for Blast appeared in the literary magazine the Egoist:

The advertisment for Blast that appeared in the Egoist magazine on 1 and 15 April. The note 'Ready April' was optimistic, as was also 'To be published Quarterly'. It is a bit of a puzzle why the loyalty of annual subscribers ('10s. 6d.') meant that they were paying more than the unconvinced who bought four issues individually (2s. 6d.), but perhaps postage had to be taken into consideration. Careful readers will notice something by its absence: any mention of 'Vorticism' or 'The Vortex'. They were words that still had to be invented for their appearance in the publication of 20 June. Image: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if copied).

The time between then and the publication of Blast on 20 June was spent developing Vorticist theory and adding additional pages – the magazine grew organically over those months. The compositors certainly had their work cut out in setting the text. It is a sad fact that none of the manuscripts used by the printers seems to have survived.

Let's take the date of 20 June at its face value, although the magazine was probably not actually issued until some time after 25 June. As the punctilious Omar Pound (Ezra's son) pointed out in his Wyndham Lewis: A Descriptive Bibliography [Pound, Omar S. and Philip Grover, Dawson / Archon Books, 1978, p. 80.] the publisher of Blast, John Lane, wrote to Lewis on 25 June insisting – wisely – that he see 'the proofs of all letter-press before publication'. Omar Pound also confirms that the print run is unknown.

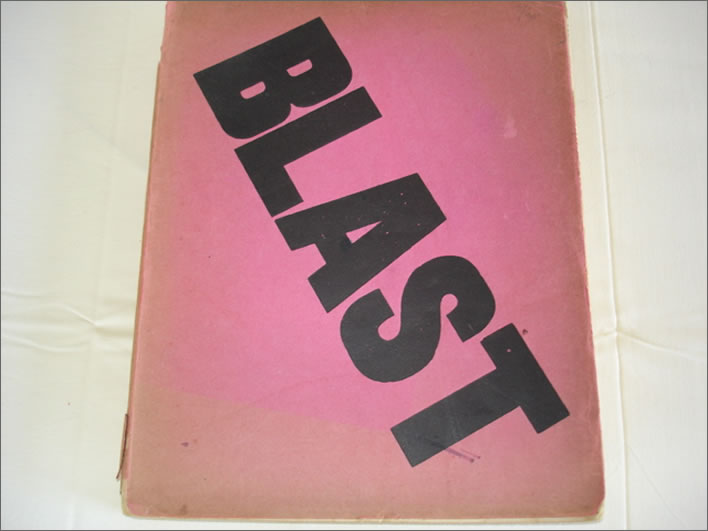

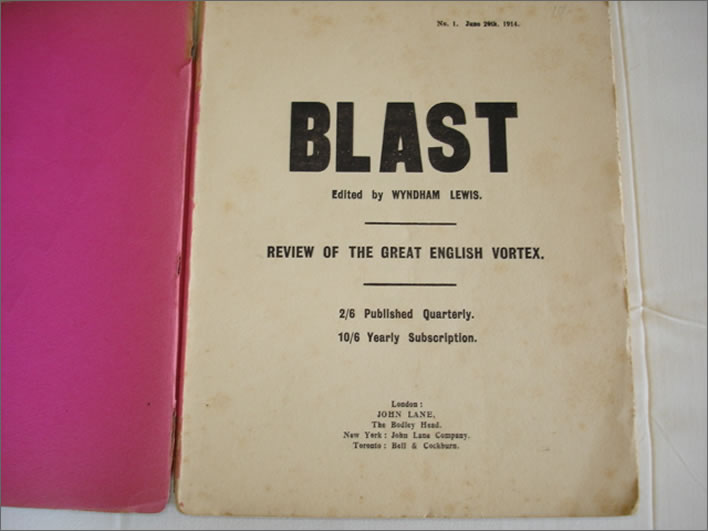

Blast was advertised as 'ready in April', but the two additional months before its final appearance were spent printing extra pages that were to be added to those already printed. In the end the magazine had a total of 158 pages – measuring 12 by 9 inches it was by any criterion a substantial product. Wyndham Lewis called it 'the puce monster'.

The puce monster

Here is its likeness, still puce after all these years:

Two photographs of the copy of Blast that passed through my hands twelve years ago in June 2006. In the Christie's London auction of 'Modern First Editions' in November of that year this copy sold for 384 GBP. Anyone investing 2s. 6d. in 1914 would have made enough for a good lunch (I have standards!) 92 years later. In the same sale the first edition of Eliot's Collected Poems, containing Eliot's autograph to F.S. Flint, fetched 2,640 GBP, the which fact may tell you a lot or nothing at all about why collectors buy books. Unfortunately, it seems that none of the participants in the creation of the first Blast had the sense to have everyone sign a few copies. Now that would have paid for quite a few very liquid lunches. Images: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if copied).

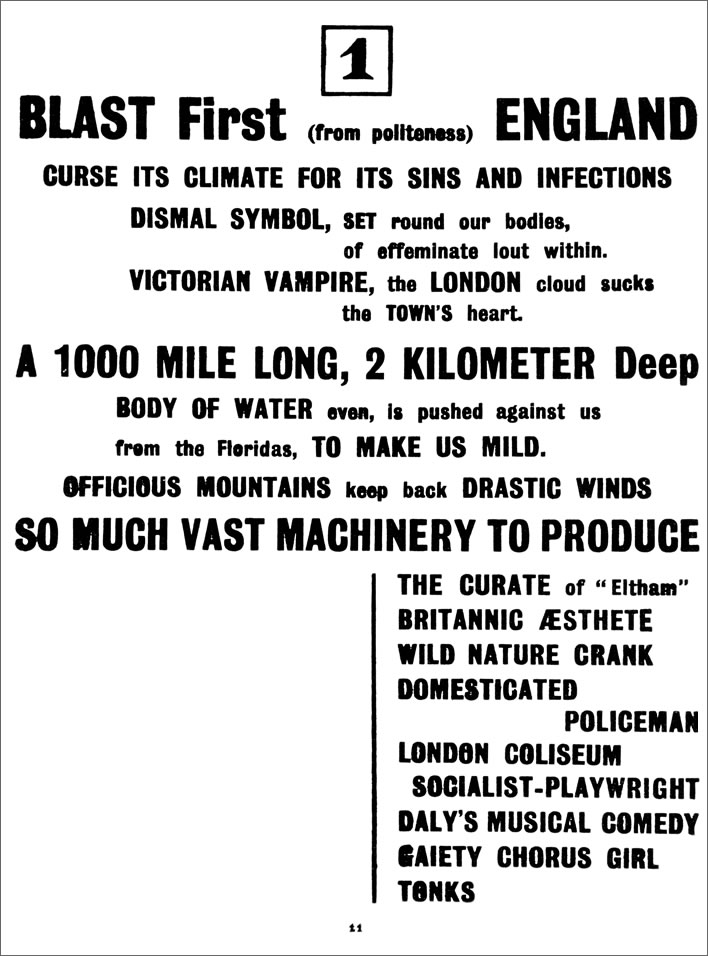

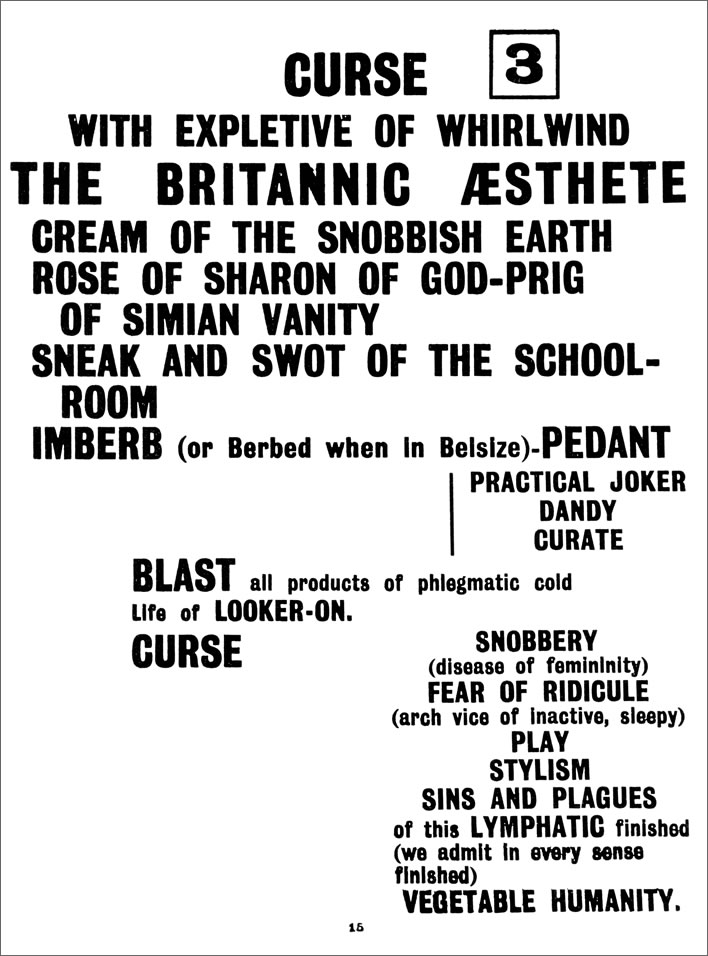

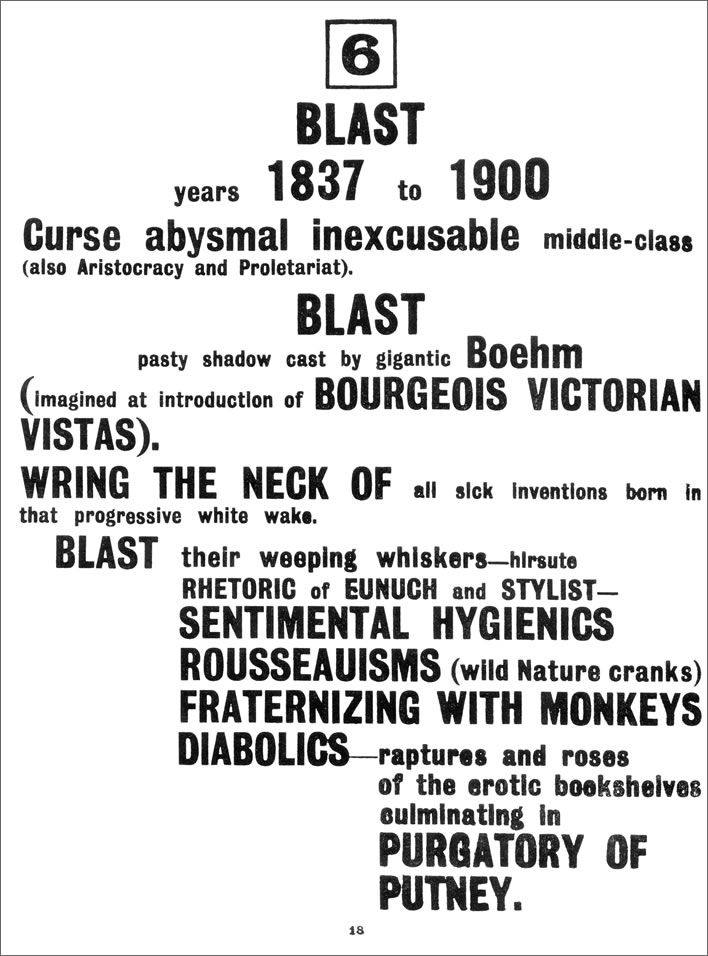

Let's look at a small sample of its blasting:

Wyndham Lewis has left us a commentary on this page:

Take my next Blast — namely, 'Blast years 1837 to 1900'. The triumph of the commercial mind in England, Victorian 'liberalism', the establishment of such apparently indestructible institutions as the English comic paper Punch, the Royal Academy, and so on — such things did not appeal to me, they appeal to me even less to-day, and I am glad to say more and more Englishmen share my antipathy. Boehm was, of course, the sculptor responsible for the worst of the bourgeois statuary which, prior to the war-sculptors, like Jagger, was the principle eyesore encountered by the foreign visitor to our 'capital of empire'. The 'eunuchs and stylists' referred to in this second manifesto would be the Paterists and Wildeites : and lastly the 'diabolics' of Swinburne are given a parting kick. For in 1914 there was still a bad hang-over from the puerile literary debauchery of that great Victorian who reacted against the 'non-conformist conscience'; who was 'naughty' before the 'Naughty Nineties' capped his sodawater wildness with a real live Oscar.

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 38.

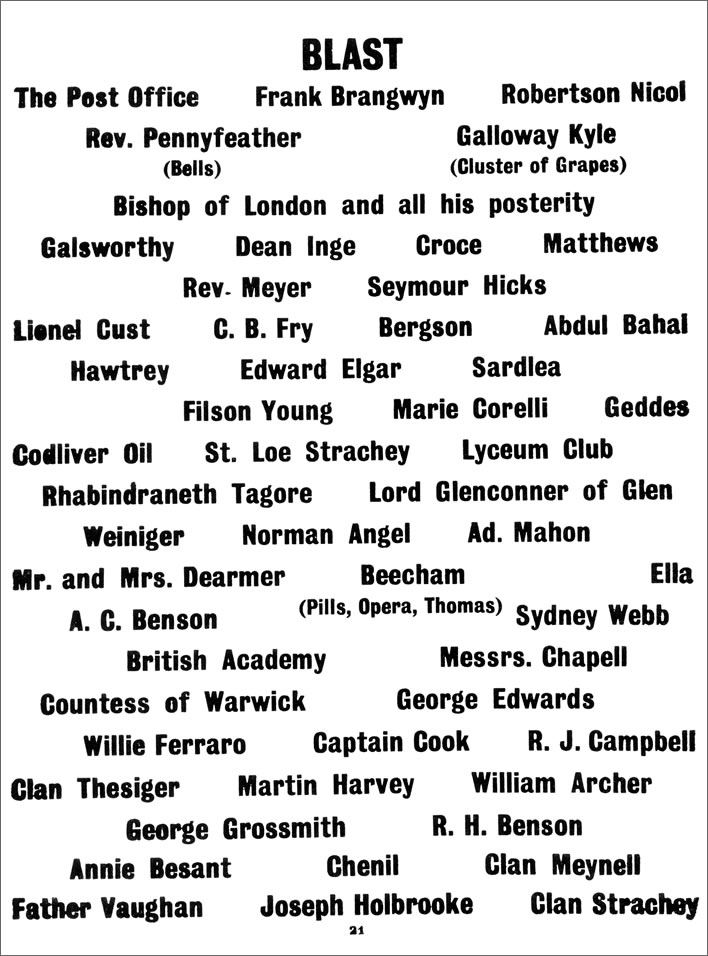

A page showing the particular objects of blasting. Image: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if copied).

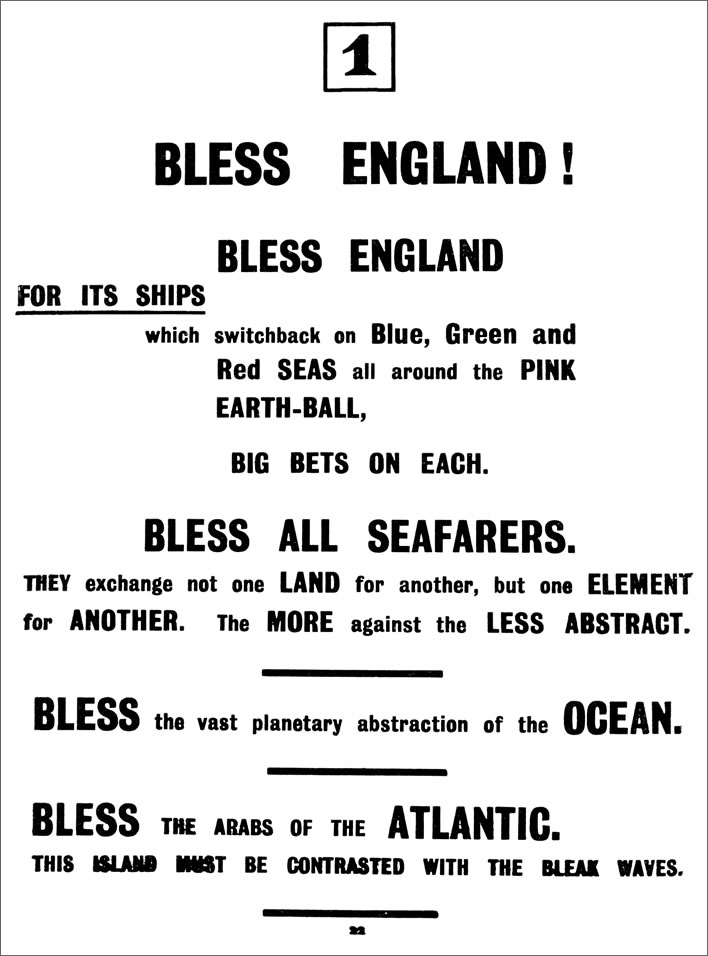

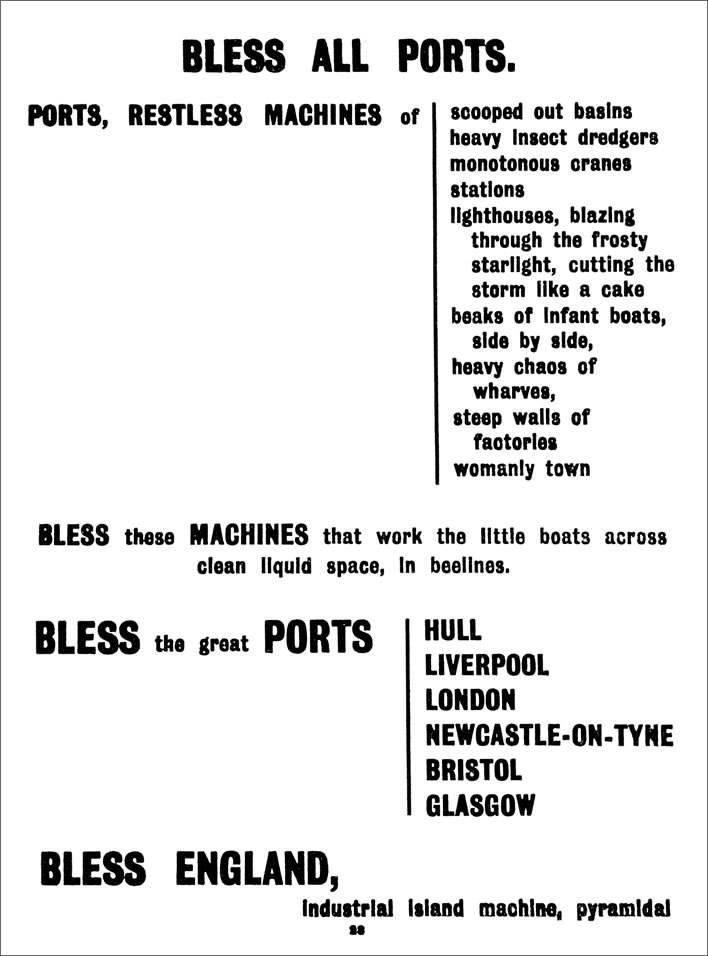

And now a few pages of the blessed:

Wyndham Lewis's comments on the above two pages:

As to 'Bless England', that requires no explanation. Our 'Island home'! And 'Bless all Ports' is just a further outburst of benediction — more 'Island home' stuff.

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 39.

A single page of the blessed. We leave the reader to sort this lot out – for example why Beecham's Pills are blasted (p. 21) but castor oil blessed. In doing so, be aware of the (deliberate?) mis-spellings, e.g. 'Bearline' instead of 'Baerlein'. Images: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if copied).

The Vorticist army marches on its stomach

As befits any respectable artistic movement, the publication of Blast was accompanied by not just one but a series of Blast dinners – or Vorticist dinners, depending on your viewpoint. Pound wrote to Joyce on 21 July 1914:

We have been having Vorticist and Imagiste dinners, haciendo politicas etc. God save all poor sailors from la vie litteraire.

Pound, Ezra The Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, p. 31.

Pound mentioned what seems to have been the principal dinner in his 1916 memoir of the sculptor Henri Gaudier Brzeska:

The appearance of Blast was celebrated in due state at 'Dieudonné,' on July 7th. Or rather the tickets were issued for July 7th, and the ceremony performed on July 15th, such being the usual proceeding of 'il capo riconosciuto.'

The feast was a great success, every one talked a great deal. It is this dinner to which Mr. Hueffer alludes in his description of Gaudier. Gaudier himself spent a good part of the meal in speculating upon the relation of planes nude of one of our guests, though this was kept to his own particular corner.

Pound, Ezra. Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir, London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1916, p. 55.

Pound alludes several times in his Cantos to the Dieudonné Restaurant, which was in Ryder Street, St. James's. The phrase il capo riconosciuto, the 'recognised head' designates Wyndham Lewis in his role as 'head of the Vorticist Movement'. The term is taken from a review of Vorticism in an Italian newspaper that James Joyce had sent him from Trieste early in July 1914 and which he prefaced to these remarks.

Ultimately, Pound's memory of that evening took on a bitter note:

In less than three weeks after the dinner the gigantic stupidity of this war was upon us, the accumulated asininity of that race which 'N'a jamais pu qu'organiser sa barbarie,' and the vanity of an epileptic had tumbled us into the whirlpool.

Pound, Ezra. Gaudier-Brzeska, p. 56. N'a jamais pu qu'organiser sa barbarie a race which 'can do nothing other than organize its barbarism'. [Pound is quoting someone here, but I have no idea who.]

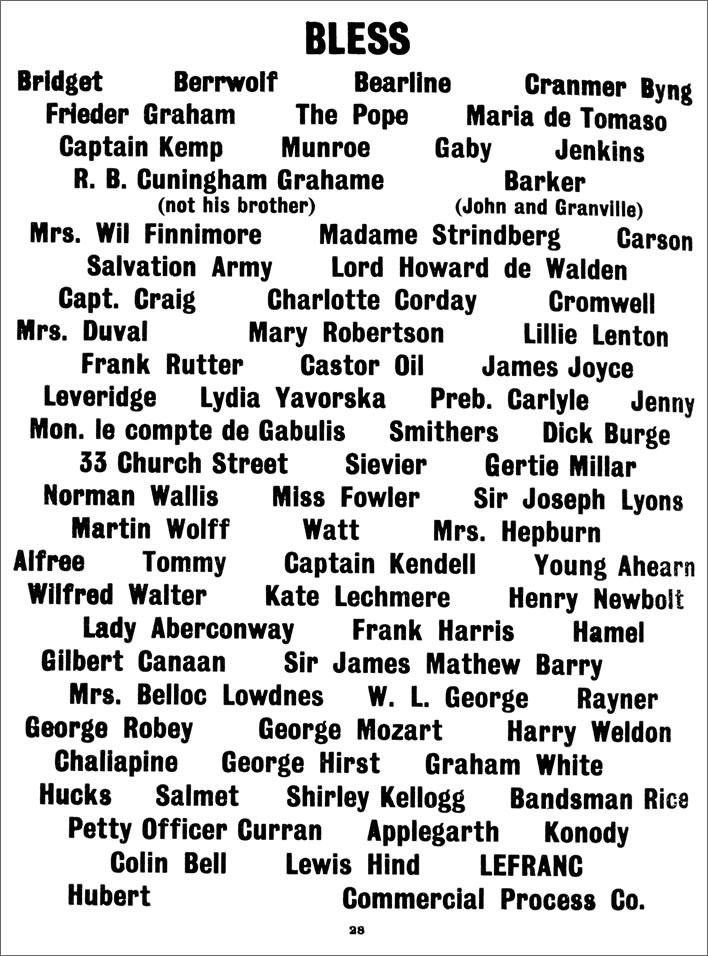

There were other get-togethers too. One was immortalised in paint fifty years after the fact by the artist William Roberts, who in 1961/62 painted his reconstruction of a scene in The Vorticists at the Restaurant De La Tour Eiffel: Spring 1915:

An imaginative reconstruction of a meeting of some Vorticist artists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, 1 Percy Street, London. Base image: Tate UK. Additional graphics: ©Figures of Speech. NB: The base image is of very poor quality; according to the Tate it is a reproduction from the Royal Academy Illustrated, 1962. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab 1536 x 1308 px].

The restaurant (which also had rooms) was taken over in 1910 by an Austrian, Rudolph Stulik. Although his biography is sketchy and unclear on many details it appears that, starting from very lowly beginnings, Stulik worked his way up to being maître d'hotel or chef de cuisine for Franz Joseph I of Austria. He gave the Tour Eiffel a reputation for fine classic French cuisine. He sold the restaurant in 1937 and died in 1938. Roberts said in an interview that Stulik is shown serving Lewis one of his favourite confections, the French classic 'Gâteau Saint Honoré', a puff pastry base filled with crème pâtissière and ornamented with balls of choux-pastry around its edge.

At this time Wyndham Lewis lived close by, at 4 Percy Street. Pound seems to allude to the restaurant several times in his Cantos as the 'Wiener Cafè'.

The reaction

By the time of the publication of the second Blast in July 1915, Vorticism had run its course, as had a lot of other -isms. The silliness, the jokes and the schoolboy humour seemed out of place in those earnest times, times when even former enthusiasts could now observe the military-industrial meat-mincer begin its work.

The question of what Blast achieved is difficult to answer. Wyndham Lewis tells us that it was the talk of literary London for a while:

Now especially in the weeks succeeding the publication of Blast, and less intensively for a number of months prior to that, I passed my time in the usual way when a 'Lion' is born. I saw a great deal of what is called 'society'.

Everyone by way of being fashionably interested in art, and many who had never opened a book or bought so much as a sporting-print, much less 'an oil', wanted to look at this new oddity, thrown up by that amusing spook, the Zeitgeist. So the luncheon and dinner-tables of Mayfair were turned into show-booths.

For a few months I was on constant exhibition. I cannot here enumerate all the sightseers, of noble houses or of questionable Finance, who passed me under review. They were legion. Coronetted envelopes showered into my letter-box. The editor of Blast must at all costs be viewed; and its immense puce cover was the standing joke in the fashionable drawing-room, from Waterloo Place to the border-line in Belgravia.

It was extremely instructive. As a result of these sociable activities I did not sell a single picture, it is perhaps superfluous to say. But it was an object-lesson in the attitude of what remained of aristocratic life in England to the arts I practised.

This lesson I took to heart; and the war concluded, I have never, except for an occasional outburst of lunching and dining, entered upon for some strictly limited purpose, consorted with what Mr. Arlen called 'those delightful people'.

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 45f.

Wyndham Lewis by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 25 February 1916. Image: ©The Universal Order / National Portrait Gallery London. NPG Ax7830

In reading the following, Schubert fans, familiar with our frequent strictures on the general uselessness of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie in supporting the creative artist, will nod their heads in agreement with Lewis:

As ever – for we have literary history to prove it – these good people of the British beau monde looked upon an artist as an oddity, to be lion-hunted from expensive howdahs. In the snobbish social sunset of 1914 I did my stuff, I flatter myself, to admiration. As regards the poor results of all this publicity I was easily the most good-natured 'lion' that ever stepped. The people I met entertained me as much as I entertained them. Rapidly I understood that the champagne of luncheon tables and the vulgar paraphernalia of butlers and druggets were all that was to be got out of them.

But this nursery of almost mindless spoilt-children was a sort of barren accolade, of a farcical celebrity. Good-humouredly I accepted it; for, indirectly, it might serve the cause of 'rebel' or of 'abstract' art and revolutionary letters, I reflected.

I was content to starve on champagne and caviare for a season. And then came down on top of all of us the greatest war of all time: came Heartbreak House, came Red Revolution, came everything that you would expect to come, upon such a long-established blank of genteel fatuity.

Blasting & Bombardiering, p. 47.

Fitting that the progenitor of Blast should end up in the Royal Artillery. Second Lieutenant Wyndham Lewis by George Charles Beresford, 1917. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG x6534

Pound, like Lewis, not only failed to receive any lasting benefit from the Blast fervour, he felt that his association with Blast had severly damaged his earnings. For him, the jokes in Blast had turned out to be expensive ones. More than most of the Vorticist group he was dependent on jobbing literary journalism and the taint of that association hit him in the pocket:

If only my great correspondent could have seen letters I received about this time from English alleged intellectuals!!!!!! The incredible stupidity, the ingrained refusal of thought!!!!! Of which more anon, if I can bring myself to it. Or let it pass? Let us say simply that Gourmont's words form an interesting contrast with the methods employed by the British literary episcopacy to keep one from writing what one thinks, or to punish one (financially) for having done so.

Perhaps as a warning to young writers who cannot afford the loss, one would be justified in printing the following:

'50a Albemarle Street, London, W.

22 October, 1914.Dear Mr Pound,

Many thanks for your letter of the other day. I am afraid that I must say frankly that I do not think I can open the columns of the Q.R. – at any rate, at present – to any one associated publicly with such a publication as Blast. It stamps a man too disadvantageously.

Yours truly, G. W. Prothero.

Of course, having accepted your paper on the Noh, I could not refrain from publishing it. But other things would be in a different category.'

I need scarcely say that The Quarterly Review is one of the most profitable periodicals in England, and one of one's best 'connections', or sources of income.

Pound, Ezra. Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, London, Faber and Faber, 1960. 'Remy de Gourmont'. p. 357f. '[M]y great correspondent' refers to Remy de Gourmont (1858-1915), the French poet and critic, a letter from whom Pound reproduced just before the present passage.

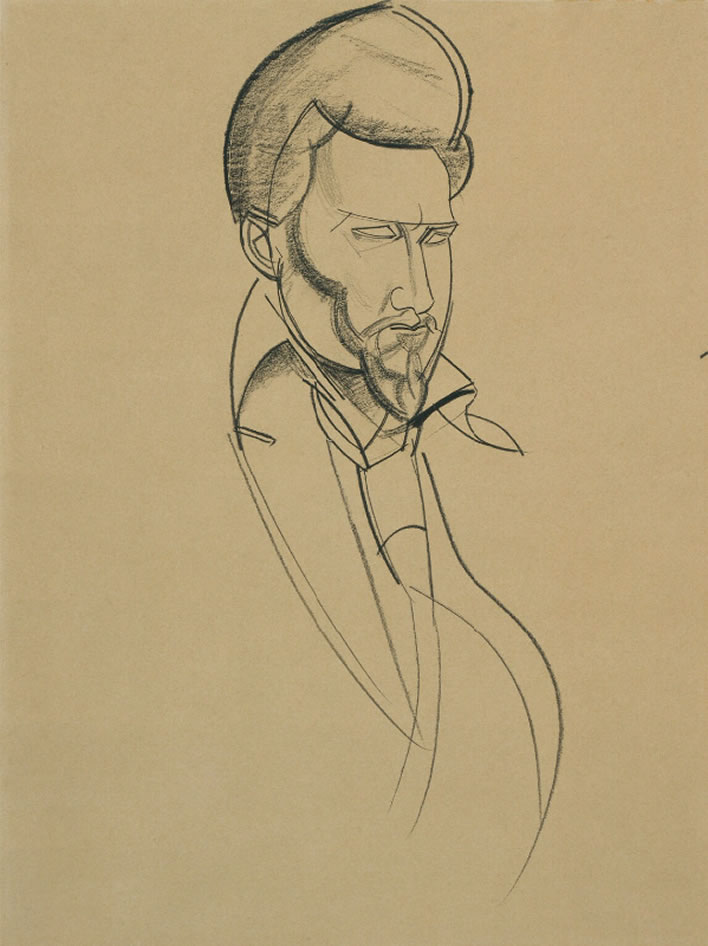

Ezra Pound, drawn by Wyndham Lewis in 1920, Pound's last year in London – he moved to Paris in January of 1921. Image: ©Wyndham Lewis and the estate of the late Mrs G A Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust (a registered charity) / National Portrait Gallery London. NPG 6728

In summary, for Pound, his association with Blast had hit him hard:

As for their laying the birch on my pocket, I compute that my support of Lewis and Brzeska has cost me at the lowest estimate about £20 per year, from one source alone since that regrettable occurrence, since I dared to discern a great sculptor and a great painter in the midst of England's artistic desolation ('European and Asiatic papers please copy.') Young men, desirous of finding before all things smooth berths and elderly consolations, are cautioned to behave more circumspectly.

Pound, Ezra. Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, p. 358.

And was there any point to Blast and Vorticism in those few months before the real storm broke over Europe?

Modern critics are divided on the value of the movement. It was fun, but what did it achieve? It is well-known that the proof of the pudding, whether it is 'Gâteau Saint Honoré' or not, is in the eating – the eating in this case being represented by the fact that Vorticism largely disappeared from the view of anyone but the most specialist critic during the period between the second issue of Blast in July 1915 and 1974, when Richard Cork curated in large measure an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London (27 March to 2 June).

For the purposes of the exhibition and in the years following, the Vorticist visual artists were retrieved from the outer darkness of the intervening years since Blast. Several critics have noted that Vorticism, swept away by the Great War, had only had time to become a programme and was never able to develop beyond that into a fully-fledged artistic movement.

Wyndham Lewis by George Charles Beresford in 1929. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG x6536

Writers are a different matter.

Ezra Pound sank down into a quicksand of verbal obscurity, complexity and incomprehensible ranting which got worse and worse as time went on. In self-imposed exile in Rapallo, then in the Pisa prison camp, then twelve years in a Washington mental institution followed by years of silence until his death he passed out of the modern literary orbit. His posthumous reputation was finished off for a generation when the true extent of his support for Mussolini was made public. There is nothing more to be done for him, as we noted nearly two years ago on this website.

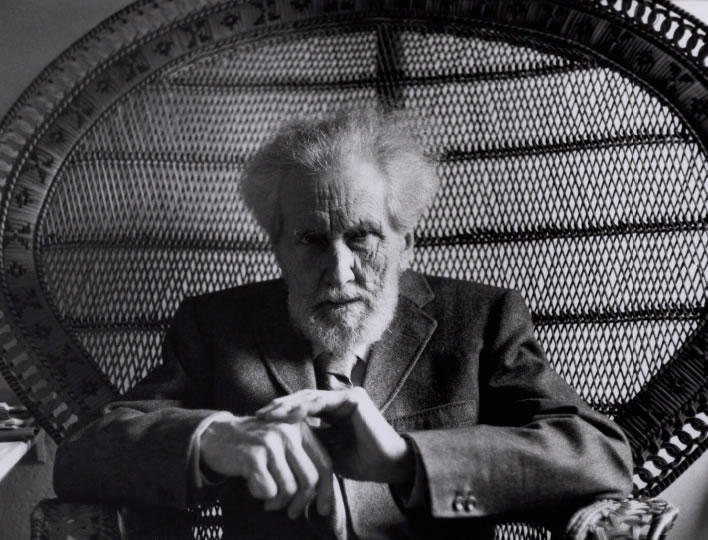

Ezra Pound in 1957, around 72 years old, photographed by Rollie McKenna, still showing us his grumpy face. Image: ©Rosalie Thorne McKenna Foundation; Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Foundation / National Portrait Gallery London. NPG x137164

Wyndham Lewis wrote tracts the apparent antisemitism of which makes many of his works indigestible in polite society. His vocal support for the early Hitler caps all that off nicely, despite his later retractions and nuances. There have been occasional attempts at a revival, but his written works are now largely unread and – tellingly – some even remain unpublished to this day.

Wyndham Lewis by Michael Ayrton, charcoal, 1955. He would live another two years after this drawing was made. Lewis had gone blind in 1951 as a result of a brain tumour crushing his optic nerve. Image: ©estate of Michael Ayrton / National Portrait Gallery, London / National Portrait Gallery London. NPG 6067

If artists really are 'the antennae of the race' it seems unfair of us moderns to expect sanity from them in the period between 1910 and 1945, a period when almost everyone else around them was losing their heads and calling it history. Perhaps the Vortex and the puce monster that it begat really did prefigure the lunacy of those thirty-five years.

Let's not even mention the seventy years since then.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!