Lottery wins

Richard Law, UTC 2018-11-04 10:47

Every few weeks another lottery obscenity comes along to mock us losers: 76.3 million here, 148.6 there. The currency doesn't matter (within limits), but the decimal point just makes the mockery worse: firstly, this is real money and secondly, your author's net worth is several decimal places to the right – not even big enough to be a rounding error.

Our initial feelings of hatred and envy are repressed – 'Good for them!' – and we focus on the important news of the day: Trump… (was that really 76.3 million?)… Merkel… (76.3 million! No more wine from a box!) Brexit… (76.3 million! A new set of winter tyres – imagine that! Perhaps even the bill paid on time.) In our hearts we know that we are made of modest stuff and lack the ambition to process such sums of money as… 76.3 million!

Just when the hatred and envy have almost been forgotten, the photographs of the winners appear in the media. People who up to now have muddled and scraped through restricted lives are now pictured jumping for joy under a downpour of champagne from a grotesquely oversized bottle. The billboard-sized cheque has to be that big in order to accommodate that obscenely beautiful amount in words.

Reading on, we learn that jobs will be abandoned, property will be bought (and then discarded soon after for something better – keeping up the listed mansion is such a bore). Our only question is: which 'partner' will dump the other first? 'Fading is the worldling's treasure, / All his boasted pomp and show. / Solid joys and lasting pleasure / None but Zion's children know'. How true, how true, we mutter – but then: how is wine from a box either a solid joy or a lasting pleasure? There is something wrong here.

In our torment we need the consolations of philosophy, another way of saying 'some sophistry to make us feel better'.

We think of the Lisbon earthquake in 1755, as the thinkers of the subsequent half century would do, which crushed, buried and drowned so many – on 1 November, All Saints' Day, just to rub it in for the religious. Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), recalling the event from his six-year-old's memories of the cultural shockwave that crossed Europe following the disaster, reflected on Matthew 5:45 'he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust', and suggested that in Lisbon it was death, not rain, that was fell on the just and the unjust. Goethe was a pantheist, remember, but, even so, 'who can explain it? who can tell you why?'

Whilst our thumb is stuck in the Bible we reflect on Job and the boils, ulcerations and scrofula he suffered as the test of faith in his God, who 'laid the foundations of the earth' [Job 38:4]. There is no mention of wine in boxes, but perhaps the Maker of the Earth and Seas took pity before imposing that terrible, last torment.

The writer and sybarite Panagiotis 'Taki' Theodoracopulos (1936-) once wrote that the real gambler – and he'd known a few of them in his time – was marked out by a belief in a great divine presence, a presence which, given the correct formula, would reward the votary with a smile and a pile of money. In between the rewards were long periods of suffering – just as for Job – and the task was to bear it with dignity and not lose faith the next time the ante clattered onto the table. But 76.3 million!

We turn to Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805). Well, why not? He was a lottery winner of a writer. He churned out poetry which he himself regarded as inferior to the great Goethe's divine gifts, but occasionally the numbers rolled kindly for him and he hit the poetic jackpot. One of his jackpot wins was his poem Das Glück, the title of which seems promising for our researches. He wrote it at the end of July 1798, so we have yet another anniversary: 220 years.

Schiller's mind, like the minds of many of his contemporaries, was afloat on an ocean of Greek divinities and heroes who enjoyed the sunshine of the Golden Age on their naked skin. The alternatives at the time were the Christian heroes who always wore clothes (rags where possible), rarely washed, enjoyed the company of lice and preferred to live in hovels.

Joachim Wtewael, The Golden Age, 1605. Summer fun, all year round.

In Schiller's Classical world, the humans who are blessed, even becoming demi-gods, are chosen even before their birth as the beneficiaries of divine grace: beauty, love, prowess in war or skill with the lyre. The chosen ones do not have to earn their status. They can 'easily defeat even the Fates', those otherwise inescapable determinants of destiny for the common ones.

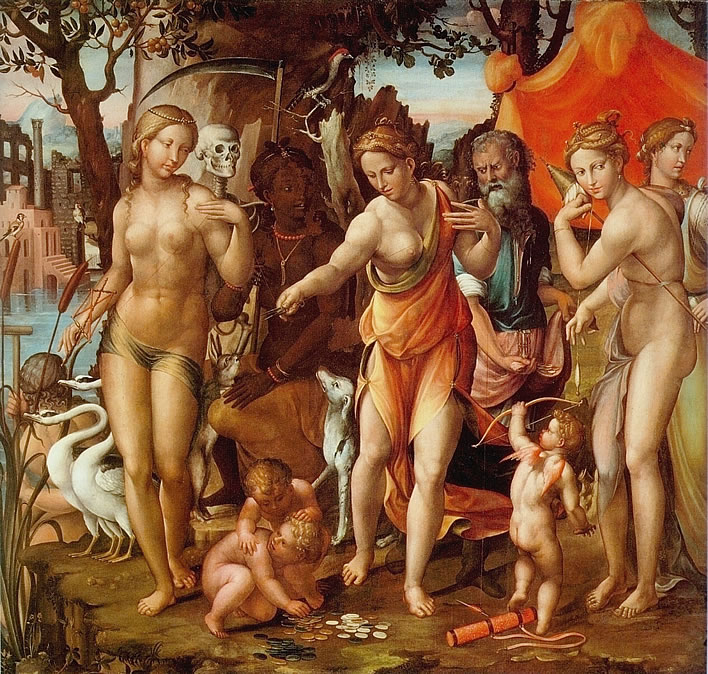

Il Sodoma, Le Tre Parche, 'The three fates', c. 1525. One spins, one measures, one cuts.

The gods choose the 'simplicity of the childish soul' and enclose 'divinity within that modest container'. Zeus 'reaches down into the mass with self-assertion, and around whichever head that pleases him he binds with loving hand the laurels and the ruler's ribbon'.

Well, most of us would go with that, Dr Schiller, but then… so what? 76.3 million! You are speaking to someone who as a kid was not favoured with the 'curly head of greening youth' but had a thin mat of brown wisps adhering to his scalp. What do we do, we, the ones who missed out on the Olympian birth lottery? And miss out on it to this day?

Do not begrudge the easy victory the gods give the lucky one, the darling of Venus whom she plucks from the battle… Do not begrudge the beauty that she is beautiful… you look at her and you are the happy one… The singer, filled with the divine, makes a god of the listener… because of his luck, you are the blessed one.

To the drinker of boxed-wine these all seem to be major disadvantages. Dr Schiller, an army doctor by training, seems to be encouraging the poor infantryman whose smashed leg he is sawing off to be happy for the gilded victor of the battle. Job's comforters spring to mind.

So far, not convincing. Finally Schiller gets to money and human striving. Let us expect more insight from him:

On the busy market Themis [~the personification of Justice with her scales] holds the scales and the reward is measured strictly according to effort, but only a god brings pleasure to mortal cheeks, where there is no miracle, there is no lucky one. Everything human has to become and grow and mature: controlling time takes it from one state to another. But you don't see luck or beauty growing: finished from eternity it stands before you.

Which helps us not a jot. Where's the justice in that? For all his fealty, the gods rewarded Schiller with ill-health and a young death (45). What I want to know is: what about my effort? Where's my effing 76.3 million?

The reader responds: Given the pathetic weakness of what you have just written, a lingering senescence softened by a box of nondescript red wine seems to be quite the appropriate and sufficient reward. There is a God.

The author replies: The reader might care to think about the subject of the divine lottery again on 11 November, commemorating that time when the golden, the silver and the bronze ones met brass and lead. Is there really?

Note: Since everyone else messes about with John Newton's hymn, Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken, I, too, took the liberty of improving the lines quoted. Much better now.

The German text of Schiller's poem is available online.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!