The Grob family

Posted by Richard on UTC 2020-07-08 14:24

The girl next door

That Franz Peter Schubert had a substantial crush on the silk manufacturer's daughter Therese Grob is beyond doubt. Some readers may think the use of the word 'crush' is disrespectful, but since Schubert's heaving passion remained locked inside his heart and was never communicated to the girl of his dreams, 'crush' seems to be the most apt word in the circumstances.

The word 'crush' is also intended as a provocation for those who like to think that Schubert never recovered his composure after his miserable failure to secure Therese Grob and that he spent the rest of his life regretting what might have been. There is no evidence for this longstanding lovelorn state at all, whether from the composer himself or his intimates.

There may have been longstanding bitterness in his soul that the operation of the Ehe-Consens-Gesetz, which came into effect in 1815, placed almost insurmountable obstacles between him, the musical freebooter, and the possibility of married bliss. But he can hardly blame that for his woes with Therese when in fact he never got around to even declaring his passion to her, even in the most anodyne terms.

The key witness to the crush is the memoir of the friend of his youth, Anton Holzapfel. As we noted in another context, unlike many of the memoirs of Schubert that were scribbled down for his later biographers, Holzapfel's account of Schubert strikes us as extremely credible. There can be no doubt that Franz Peter's crush on Therese was real.

The other memoir often cited in this respect is that of Anselm Hüttenbrenner, which, in contrast to Holzapfel's credibility, is utterly unbelievable in almost everything it says. On numerous occasions on this website, we have had cause to demolish some tale from one or other of the Hüttenbrenner brothers (for example here and here). For that reason we are not even bothering with Hüttenbrenner's remarks on Schubert's crush.

Here is the beginning of Anton Holzapfel's account:

Whether a note about Schubert's first youthful passion – which probably remained unrequited – for a girl from a good middle-class family by the name of Therese Grob will be useful for your biographical purposes I cannot judge. For all the details that are unknown to me I can only refer you to Schubert's brother. I allow myself only the certainly obvious remark that Schubert's feelings were intense and locked away deeply within him. They were certainly not without influence on his first works, for in the Grob household music-making was taken seriously.

Ob eine Notiz von Schuberts erster, wahrscheinlich unerwidert gebliebener, jugendlicher Leidenschaft für ein Mädchen aus gutem bürgerlichem Hause, namens Therese Grob, Euer Wohlgeboren biographischen Zwecken förderlich sein mag, kann ich nicht beurteilen und muß rücksichtlich der allfälligen mir ganz unbekannten Details auf Schuberts Brüder weisen und erlaube mir nur die gewiß naheliegende Bemerkung, daß Schuberts Gefühle tief verschlossen und heftig waren und gewiß nicht ohne Einfluß auf seine ersten Arbeiten blieben, da im Grobschen Hause solide Musik getrieben wurde. [Erinn 69]

According to Holzapfel, Franz Schubert, in comparison with his noisy peers, was usually taciturn and uncommunicative. In this respect it was typical for Schubert that he could not bring himself to talk about his passion for Therese Grob but instead wrote of it in a letter to Holzapfel:

…Franz Schubert did not tell me about his passion for Therese Grob orally, which he could have done very easily in private, but rather communicated it to me in a long, enthusiastic letter, unfortunately now lost. I tried ridiculously to dissuade him from this love in a lengthy, sermonizing epistle, which at the time seemed to me to be extremely sage. This latter, the draft of which I still have, is dated as the beginning of 1815.

…daß mir F. S. seine Neigung für Therese Grob nicht mündlich, was er sehr leicht hätte unter vier Augen tun mögen, sondern in einem längeren, enthusiastischen, leider verlorenen Briefe mitteilte, von welcher Liebe ich ihn lächerlicherweise durch eine weitläufige, mir damals höchst weise dünkende, chrienmäßige Epistel abzubringen suchte. Letztere, deren Entwurf ich noch vorfand, ist vom Anfang des Jahres 1815 datiert. [Erinn 70f]

All traces of the correspondence between Holzapfel and Schubert on the subject of Therese have been lost: Schubert's original letter and Holzapfel's in draft or final form. What a find they would be!

About Therese Grob I can only reliably tell you the following. She was the daughter of a middle-class woman, still in the prime of life, who also had a son, Heinrich. She was a widow and the owner of her own house in Lichtental, not far from the church. She also successfully ran one of the silk-weaving businesses that were flourishing at that time. The Schuberts were all well known to the family, whether as teachers or as friends and musical compatriots of the son in the family. By chance I was present one evening for a musical celebration of the name-day of Theresia in 1811 or 1812.

Über Therese Grob vermag ich Folgendes verläßlich mitzuteilen. Sie war die Tochter einer noch in kräftigen Jahren stehenden bürgerlichen Frau, welche auch einen Sohn namens Heinrich hatte und als Witwe und Besitzerin eines eigenen Hauses im Liechtental unweit der Kirche eines der damals gerade in guten Schwung gekommenen Seidenweber-Geschäfte glücklich betrieb. Die Schuberts waren alle teils als deutsche Lehrer, teils als Jugend- und Musik-Freunde des Sohnes im Hause wohlbekannt, und so brachte ich bei Gelegenheit der musikalischen Feier eines Theresienfestes ungefähr im Jahre 1811 oder 1812 gleichfalls einen Abend in dieser Familie zu. [Erinn 72]

It is a testament to Holzapfel's memory and credibility as a memoirist that almost every one of these statements can be substantiated against documentary sources. Unfortunately, only the celebration for the name-day 'Theresia' cannot be verified directly.

The name-day was considered to be more important than the birthday at the time in Catholic families. In the case of the Grob family even more so, since mother and daughter both shared the name Therese/Theresia and would celebrate their shared name-day together, on 15 October (the death date of Saint Teresa of Ávila 1515-1582). The musical evening was probably held on the previous day.

Therese was certainly no beauty, but well-formed, rather plump with a fresh, childish round face. She was an accomplished singer with a beautiful soprano voice who sang in the choir in Lichtental, where I with Schubert and other young musical friends often heard her sing. Schubert wrote several pieces for her, in particular an exceptionally lovely 'Ave' in C.

Therese war durchaus keine Schönheit, aber gut gewachsen, ziemlich voll, ein frisches kindliches Rundgesichtchen, sang fertig mit schöner Sopranstimme auf dem Chore im Liechtental, wo ich mit Schubert und andern jungen musikalischen Freunden sie oft singen hörte. Schubert schrieb für sie mehreres, besonders ein wunderliebliches 'Ave' in C. Damals war der Regens am Liechtentaler Chor Herr Holzer, ein etwas weinseliger, aber gründlicher Kontrapunktist, bei dem alle Schubertschen Brüder Musikunterricht nahmen. Theresens Bruder Heinrich, welcher nach der Mutter Tode das Geschäft fortsetzte und sich als Geschäftsmann bedeutend aufschwang, war ein fertiger Klavier- rücksichtlich Orgelspieler, und so wurde das Grobsche Haus unserm Fr. Sch. zugänglich und wichtig. [Erinn 72]

[Otto Deutsch notes that no Schubert 'Ave Maria' exists (with the exception of the much later Ellens dritter Gesang); the song Holzapfel misremembered was perhaps the 'Salve Regina' in F, from 1815 D 223.]

Therese's brother Heinrich, who continued the business after the mother's death and who had great success as a businessman, was an accomplished pianist and organist, and thus the family was accessible and important for our Franz Schubert.

Theresens Bruder Heinrich, welcher nach der Mutter Tode das Geschäft fortsetzte und sich als Geschäftsmann bedeutend aufschwang, war ein fertiger Klavier- rücksichtlich Orgelspieler, und so wurde das Grobsche Haus unserm Fr. Sch. zugänglich und wichtig. [Erinn 72]

The Swiss silk weavers

The Grob family became a substantial part of what we might term the Lichtental experience for the Schuberts. Originating from Switzerland, they appear to have established themselves about the time that Franz Theodor and Elisabeth Vietz arrived.

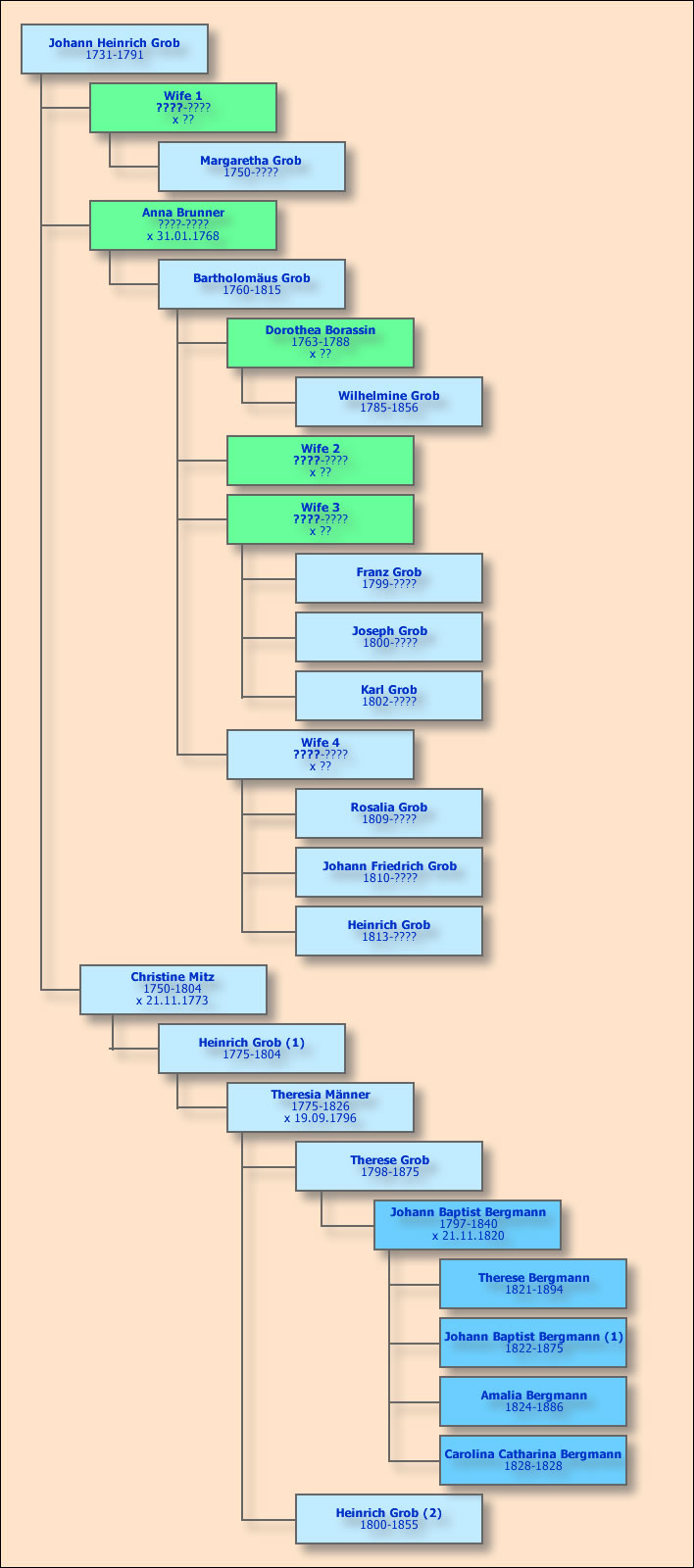

As the following chart shows, during the period between 1785 and 1815 there were 16 members of the family in Lichtental at various times and in various combinations. Why these two dates in particular?

The year 1785 was the year of the wedding of Franz Theodor Schubert and Elisabeth Vietz and the birth of their first surviving son, Ignaz Franz. Their full presence in Lichtental came the year after, when Franz Theodor became the schoolteacher at the school in Himmelpfortgrund 72.

It was also the year that Bartholomäus Grob's daughter Wilhelmine was born in Lichtental, thus establishing his presence there. His father, Johann Heinrich, had arrived in Vienna perhaps a dozen years before that.

The year 1815 was the year in which Bartholomäus Grob, the last of the Swiss ancestors, died in Vienna, leaving seven children, six of them still underage.

The presence of the Grob family in Lichtental 1785-1815.

The Grobs originally came from Switzerland. Johann Heinrich Grob was in Vienna by 1773 (his marriage to Christine Mitz); his son Batholomäus arrived in Vienna sometime after 1785, that is, just before our period begins.

The 16 members of the family who were living in Lichtental at some point in the period 1785-1815 are represented in pale blue boxes and wives who had died are represented in pale green boxes. The darker blue boxes represent the future husband and children of Therese Grob.

Note: this diagram is not intended as a comprehensive genealogical tree for the descendants of Johann Heinrich Grob – the multiple marriages of Johann Heinrich and his son Bartholomäus are not fully represented and children who did not survive until the period in question are not included in the chart.

There are in effect two lines of Grob descendants: the descendants from the progenitor Johann Heinrich through his son Heinrich (1) and the line descending through his son, Bartholomäus. For the sake of our sanity we should try to keep the two lines of the Grob family separate in our minds, despite their close intermixing in daily life.

The move to Vienna

One defining characteristic of both branches of the Grob family is their economic success. Johann Heinrich, a silk manufacturer, came from Switzerland to the imperial capital and found a growing market for his products. His son Bartholomäus seems to have taken a detour via Berlin for some years, before joining his father in Vienna.

We do not know the precise reasons for the Grobs' wanderlust, but the historical background to these times may help us to understand it.

The luxury law

After the Reformation (1517~1648), most parts of the country we now call Switzerland had become Protestant in the most Calvinistic sense. It was therefore never going to be a market for luxury goods such as silk cloth. In addition, the 18th century was a time of social turmoil and endemic corruption in the various cantons – it would take another century before Switzerland became the peaceful democratic confederation of recent legend.

Then, on 12 September 1749, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresia (1717-1780) issued the decree that became known as the Luxusgesetz, the 'Luxury Law'.

Not a year after the end of the ruinous War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) she felt it necessary to remind the members of the feudal aristocracy of their duty of economy in those straightened times. At a push, a ball gown might even be worn twice (with a few minor changes); but above all, one should not buy one's fineries from abroad.

The French in particular had made a good living from the fashion envy of the Austrian aristocracy, but Austria could no longer afford the leakage of money out of the country.

It is one of those ironies of history that we so enjoy, that when she came to make the wedding of her beloved first son Joseph in 1760, a mere decade after her Luxury Law, no expense was spared. The degree of her profligacy shocked even normally urbane French observers, as would the excesses of her daughter, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), a couple of decades later.

Despite being honoured more in the breach than in the observance, this law led to the growth of luxury trades within the empire itself. Ironies come seldom alone: at the moment that the Industrial Revolution in Britain was beginning to change the economic basis of the world, with coal, steam, iron, steel and factory production of cheap goods, the economic and mercantilist backwater that was Austria was importing handworkers making luxury goods.

Tolerating Protestants

The Grobs, father and son, took the hint and set off to exploit the new demand for the production of silk cloth in Vienna. The son, Bartholomäus Grob, tried his hand for a few years in Prussia, possibly because he was an unbending Protestant (and would remain so until his death), but it seems that Vienna was ultimately where the economic action for luxury goods was.

That very many of the artisan craftsmen who moved to Austria were sturdy Protestants was an inconvenient fact which the piously Catholic Maria Theresia never resolved. She was schizophrenic on the point: she wanted bright entrepreneurs to get the agrarian, feudal economy out of its mercantilist swamp, but why did they always have to be these satanic Protestants (who were just as bad as the Jews in their own way)?

Consequently, throughout her reign she oscillated between half-hearted toleration and vicious persecution of all non-Catholics. Protestants could not worship together even in their own homes, could not build churches, were mistreated, deported to the distant east and/or set upon by murderous mobs. Families were split up, the breadwinners deported into virtual slave labour or military service and their wives and children left to muddle through as best they could.

In the year following her death in 1780, her son Joseph II (1741-1790) introduced his Toleranzpatent. It was full of contradictions and impracticalities, as with all Joseph's madcap improvisations, but at least it allowed most Protestants to live their economically valuable lives in relative peace.

It is suggestive for us dreamers and fantasists that the year of Joseph's famous Toleranzpatent, 1781, is around the time that the life-long Protestant Bartholomäus Grob decided to up sticks in Berlin and come to join his father, Johann Heinrich, in the now blooming Viennese silk industry. Their businesses would flourish: in the coming decades the citizens of the Empire sensibly forgot about revolutions and constitutions and turned their thoughts to hats and waistcoats and ribbons and tresses and swishing dresses and dancing. Very wise.

Economic destinies

In the Himmelpfortgrund and Lichtental communities we can identify various economic destinies, which must have been quite common destinies for the time.

Franz Theodor Schubert and his brother Karl obtained modest prosperity in the flourishing teaching business. They played the game well and seized their opportunities whenever they came along.

Michael Holzer stagnated in his limited job and seems to have just run out of income or the initiative to acquire it – or perhaps even just poured it down his neck.

Ignaz Wagner sank into poverty: the cobbler, the symbol for the lone handworker, rarely rose to success: there were only so many hours in the day that one man could cobble and, adrift in an ocean of cobblers, only so much that could be charged for the product.

Ferdinand Holzer, Michael's father, started out as a journeyman silk stocking weaver but ended up making wooden clocks – another limited market.

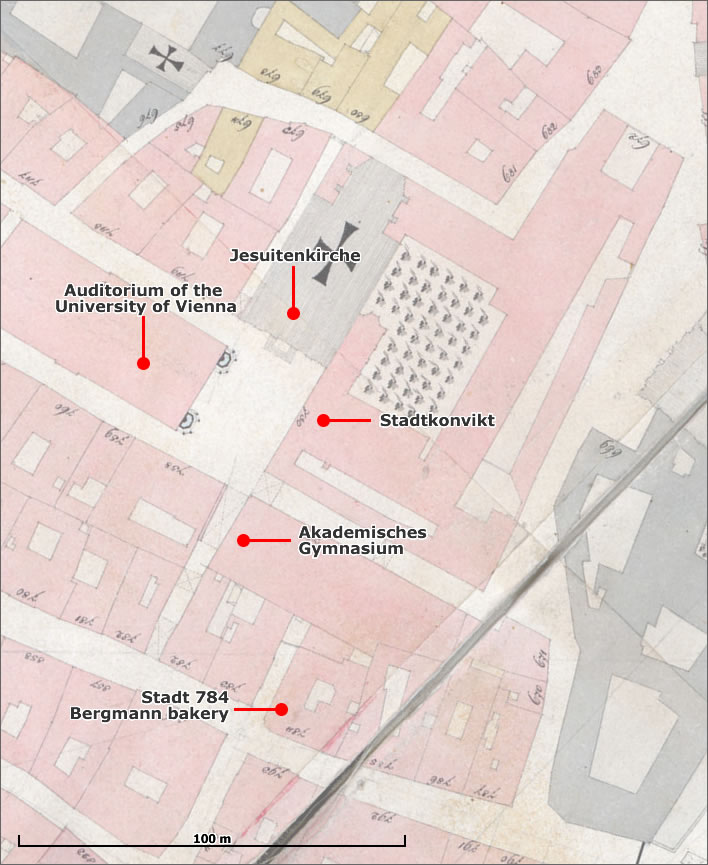

Johann Bergmann, the master baker who married Schubert's beloved Therese Grob, made a solid, though not sensational living at his trade. He was admittedly limited to one outlet, but it would have taken particular incompetence not to have made money in patisserie-mad Vienna.

On his death in November 1840 Johann left a modest inheritance for his widow and family which had been swallowed up in medical and burial costs, but she was well provided for by money coming from the silk businesses in the family and lived another 35 years without any financial worries.

In contrast to them all, the Grobs were capitalists and industrialists: they employed others and could expand their activities to produce even more money. The founding fathers did well, as did Theresia, the widow of Heinrich (1), who ran the business in exemplary fashion until it could be handed on to Heinrich Grob (2), the clever son, the friend of Franz Peter. He studied hard, professionalised ownership and built a fortune on the foundations his parents had laid.

Footprints in time

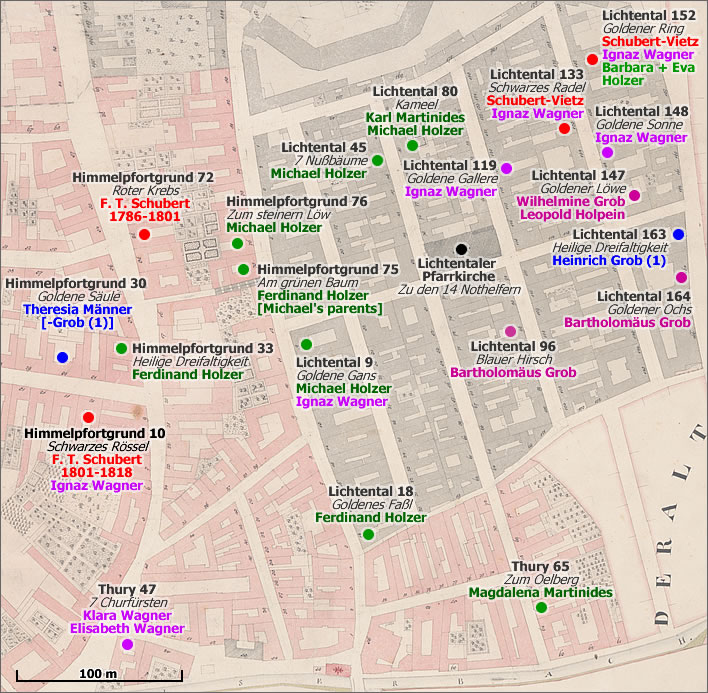

The map below shows the 'footprints' of some key members of the Himmelpfortgrund and Lichtenstal community during the period 1785-1815. Most of the locations marked were not continuously occupied during this period by the same people: hence we speak of footprints, traces left in the documentary record as people were born, married or died.

But the key point is that each of these people is linked to the others in multiple ways. We only need to note that, in this close community, everyone lived less than 500 m from everyone else and that the church where Schubert composed and played, where Holzer composed and played, where Therese Grob sang and where all the other musically inclined members of their circles did their thing is almost at the geographical centre of the district and would have been at the cultural centre of a pious Catholic community.

Residences of the Schubert, Wagner, Holzer and Grob families 1785~1820. Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Thury, Lichtenthal 1821. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

The narrative version of this map might run as follows:

Franz Theodor and Elisabeth Schubert arrived in Lichtental in 1784. We assume that Franz Theodor continued to teach at his brother's school in Leopoldstadt. Their first footprints in Lichtental fall together with those of their close friends, Ignaz and Elisabeth Wagner – the two couples shared some pokey rooms in Lichtental 152 and then 133.

When Franz Theodor Schubert finally landed his teaching post at the school in Himmelpfortgrund 72 their paths diverge until sometime after 1818, when Ignaz moved into a room in Himmelpfortgrund 10, Franz Theodor's former school which he continued to own and rent out as apartments. Klara, Ignaz Wagner's sole surviving daughter trained as a midwife. She died 40 years old in 1818. Her mother, Elisabeth Wagner, Ignaz's wife, had died here, 63 years old, in 1810.

Ferdinand and Rosalia Holzer, Michael Holzer's parents, moved to Himmelpfortgrund 33 around 1768. Michael was born here in 1772.

Rosalia, Ferdinand Holzer's first wife, died in 1800 at Lichtental 18. Ferdinand's second marriage, to Anna Weinmann (-Hakschingl), was strained. After she died in 1807 the now 69 year-old Ferdinand didn't hang around: he walked his third wife, Theresia Hubert, down the aisle in 1808. Ferdinand died at the age of 75 in 1814.

In 1794 Michael Holzer married the daughter of Karl Martinides, the incumbent of the post of choir master at the Lichtental parish church and moved in with her in Karl's residence of Lichtental 80. When Karl died later that year, Michael was perfectly placed to take over his father-in-law's job.

Over the next few years the family lived in Lichtental 9 and Himmelpfortgrund 76, which is where Michael Holzer died in 1826. Michael's sister, Magdalena Martinides, also lived nearby: she died aged 72 in 1807 at Thury 65.

Two of Michael's older siblings would end up living in Lichtental 152, where they died in 1827 and 1835. With that the circle closes: Lichtental 152 happens to be the house where Franz Theodor Schubert and Elisabeth Vietz and their friends Ignaz and Elisabeth Wagner left one of their first footprints in Lichtental in 1783.

The two lines of the Grob family, Bartholomäus and Heinrich (1), arrived in Vienna at different times. Bartholomäus Grob settled in Lichtental 164 and his half-brother Heinrich Grob (1) settled in Lichtental 163. Both brothers were weaving silk, as was their neighbour and friend at Lichtental 166, the local magistrate Johann Wagner, making that corner of Lichtental into a small industrial estate for silk manufacturing.

Bartholomäus Grob's daughter, Wilhelmine Grob, was born in Berlin in 1785. She married the coin engraver Leopold Hollpein in 1807. They made their home in Lichtental 147 and became part of the Grob colony there. After Hollpein's death she married Ignaz Schubert in 1836, thus creating one more link in our web of interrelationships.

During this period, although some people moved around frequently between residences, most people remained in the area for nearly all of their lives.

There are three exceptions to this: most obviously Franz Peter Schubert, most of whose adult life was spent in the Innere Stadt of Vienna; then his parents, who in 1818 moved to the rebuilt school in the Rossau suburb, just a few kilometres to the south; and, of course, Therese Grob, Schubert's secret passion, who moved to the baker's shop in the Innere Stadt when she married Johann Bergmann.

Johann Bergmann's bakery in the environs of the Stadtkonvikt, the Jesuitenkirche, the Akademisches Gymnasium and the Aula of the University of Vienna. Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Innere Stadt 1824. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!