Icon

Posted by Richard on UTC 2025-03-01 17:00

A short while ago I wrote that Winston Churchill was a 'global icon'. I used the word reluctantly, but I had resisted using the words 'icon' and 'iconic' long enough and anyway, I couldn't think of a better word. In every corner of modern culture we find these words being used and we all know what they mean. They clearly fulfill a need, so why not?

This modern use of 'icon' was taken up by the Oxford English Dictionary in 2001: 'A person or thing regarded as a representative symbol, esp. of a culture or movement; a person, institution, etc., considered worthy of admiration or respect.' That seems about right.

Although I'm not one of those etymology pedants who mistakenly tell people off who write 'data is', I do like to know where my words come from. In the case of 'icon', its origin is a bit of a worry. The modern usage hardly corresponds to the word's traditional etymology.

In these days of internet hyperbole, we clearly needed a word that meant something like 'recognised as very important by a large number of people; setting a trend; being of great (usually cultural) significance; standing out from the rest'.

But why use 'icon' and 'iconic'? Using the same word to mean different things is a recipe for confusion (v. 'decimate', 'aggravate'). Until very recently (1952) the OED tells us that for the preceding four hundred or so years, 'icon' has been used as a near-synonym for 'image', particularly in the sense of a representation of some sacred personage in the Orthodox Church, the which image itself is frequently an object of veneration.

Which is fine, but how do we get from a Greek word εἰκών, εἰκον- 'likeness, image, portrait', via late Latin īcōn (ditto) then via a word referring to a Greek Orthodox (reverential) image, then to the icon Winston Churchill in the modern definition?

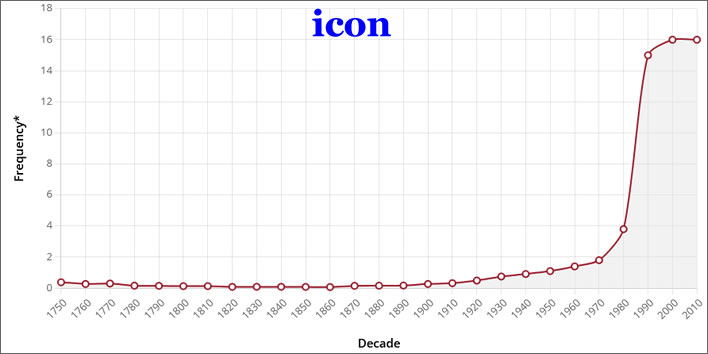

There is a discontinuity in the chain of meaning – an existing and well understood word was captured for this new, quite different meaning. According to the OED, the modern sense of icon first appeared in 1952. A frequency graph of the occurrence of 'icon' is here. Remember that these frequencies relate to all the various meanings of the word:

Top: Frequency graph for written occurrences of the word 'icon' between 1750 and 2010. The y-axis is the number of occurrences per million words in written English [i.e. in 2010 the word 'icon' occurred about 16 times on average in every million words].

Bottom: Frequency graph for written occurrences of the word 'iconic' between 1770 and 2010. Images: Oxford English Dictionary.

We see that from 1750 to about 1960 the word 'icon' was a rarity. From 1960/1970 onwards the use of the word exploded. Since there wasn't a sudden interest in Greek Orthodox art we can assume that it was the new meaning that 'went viral'.

The same can be said for the word 'iconic', though its frequency of occurrence is a little different – a warning to us not expect great accuracy in such statistical samples. The highest incidence is about 1.7 occurences per million words, appreciably fewer than 'icon' with 16 occurrences in every million words. Until the 1930s, 'iconic' was as good as non-existent.

When we look at the historical development of these two words we realise that the frequencies of their earlier meanings are almost disappearingly low in comparison to the modern usage. Given the overwhelming frequency of the modern meanings, we need have no doubt that anyone, apart from scholars of the Byzantine era, will be confused by the new meanings.

So now we ask: what happened in 1960/1970 to cause this sudden popularity of the new meaning of 'icon'? Andy Warhol (1928-1987), that's what happened.

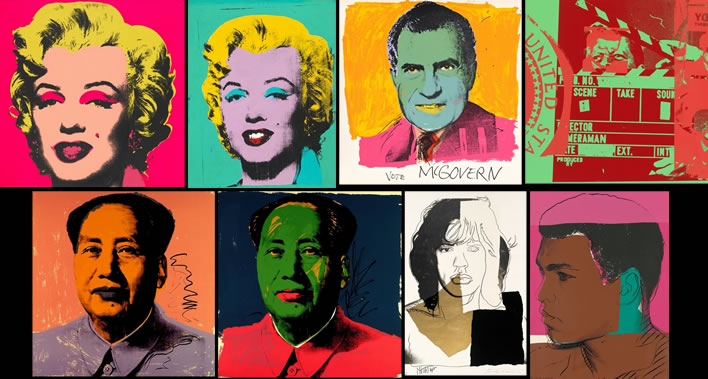

Warhol made his early reputation in the 1960s and 1970s with silkscreens of universally recognized things and people. We are all familiar with these works: Campbell's soup tins, Marilyn Monroe, Coca-Cola bottles, Elvis Presley, JFK, Elizabeth Taylor and so on. They have become in themselves iconic.

Warhol took as his subjects people or things that were already known to nearly everyone in the world – they were not merely famous, they had a deeper cultural significance and as such they were already icons. He then 'iconised' them in striking images, creating images that were themselves icons of icons.

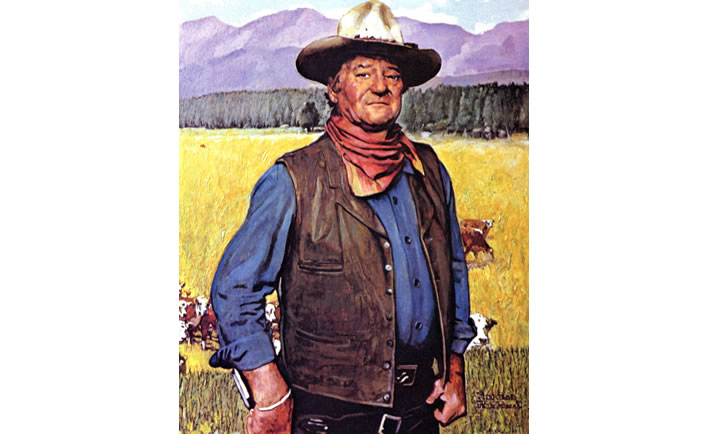

Warhol's process of iconisation is too complex to discuss in detail here. We can get a hint of it if we just carry out a thought experiment in which Warhol simply produces conventional portraits of his subjects. But, however stylish, beautiful or photorealistic they might be, we certainly wouldn't call such works iconic.

Norman Rockwell's non-iconic portrait of the icon that was John Wayne, 1973.

Instead Warhol creates them with the techniques of mass production and often produces sets of variations on the same base image. Each reproduction and each variation adds a level of significance to the subject. The subject passes from everyday realism into mythic symbolism. One Warhol Marilyn is an arresting image; a dozen variations make her iconic.

Nowadays, anyone describing one of Warhol's Marilyn images would call it 'iconic' and everyone would nod in agreement. Warhol brought the Greek Orthodox icon into the 20th century.

Associating the terms icon and iconic with Warhol's works isn't the flight of fancy it may seem. His parents were first generation immigrants who came from the east of the Austro-Hungarian empire and who were Ruthenian Catholics – Catholics with a Greek-Orthodox flavour. There can be no doubt that Andy Warhol grew up surrounded by Orthodox religious imagery, particularly icons in the traditional sense of religious images. After a life that few would call religious he was buried according to that faith, near to his parents in a Byzantine Catholic Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

I have no idea what went on in Warhol's head (if anything) as he was working his way towards his iconic style, with his iconic images of twentieth century icons. More research needed.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!