Schubert portrait Whac-A-Mole

Richard Law, UTC 2020-01-05 10:48 Updated on UTC 2020-02-16

Reader Annette, in a comment on our first article on the pictorial representations of Schubert, directed our attention to a painting by the Hungarian artist Gábor von Melegh (1801-1835) in the Hungarian National Gallery, which the gallery claims to be a portrait of Franz Schubert.

Another piece to add to our collection of supposed portraits of Schubert.

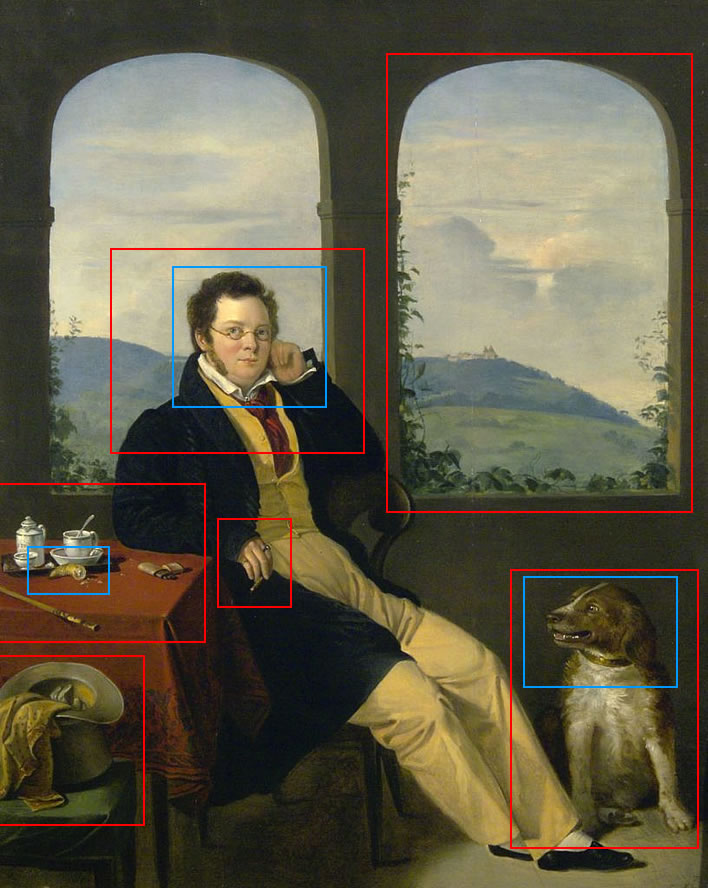

Gábor Melegh, Portrait of Franz Schubert, 1827. Image: Hungarian National Gallery.

The enthusiastic certainty of the gallery's title for the piece Gábor Melegh: Portrait of Franz Schubert, 1827 is not really repeated in the accompanying text:

Gábor Melegh (1801–1832), hailing from Versec in Temes County (today: Timiș County in Romania) began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in 1817 and with some short interruptions he lived in the Austrian capital for the rest of his life. We mainly know his portraits and lithographs, of which there are regrettably not too many but all of them distinguished by their high quality. In their studies Dénes Pataky and Anna Jávor explored Melegh’s oeuvre, while in a study in 1987 Ágnes Vayerné Zibolen discussed the history of this Schubert portrait and the painter’s liaisons within the Viennese art circles. Virtually nothing is known about the circumstances of the making of this picture. Although no available written records document Melegh and Schubert’s acquaintance, the friends they had in common, the many artists (primarily Károly Kisfaludy) they both knew, and the venues they attended together in Vienna provide sufficient grounds to assume that the two artists personally knew each other. This portrait is likely to prove the same.

The executive summary: there is no documentary evidence at all – nothing (not even 'virtually' nothing) – that this is a portrait of Schubert.

Now that the gallery has convinced itself that this is a painting of Schubert, it can analyse the iconography in the painting accordingly:

Like Biedermeier depictions in general, this Schubert portrait also lacks any pictorial allusions to the composer’s genius, or the 'greatness' and confidence of the 'chosen artists'. The picture shows not a great master but a middle-class individual delighting in the small gifts of life. We see Schubert, a passionate smoker and coffee drinker, sitting on a cosy veranda with his loyal dog, Drago, with the mountainous landscape of the environs of Vienna in the background. Still-life elements are given a special role: the table with cigarillos, a coffee set and a half crescent-roll evokes the image of middle-class prosperity and the attractive world of the Viennese Biedermeier through these objects. The figure of Schubert embodies a classical member of the middle-class, the Viennese citizen humbly enjoying the joys of life.

On reading this, the Schubert cognoscenti who patronise our website, when they have stopped laughing, will be wondering whether the stuff they smoke in the Hungarian National Gallery is available by mail order. It would certainly disperse those January blues.

Facing facts

Let's wash all the assumptions out of our heads, breathe into a bag a few times and look at Melegh's painting dispassionately.

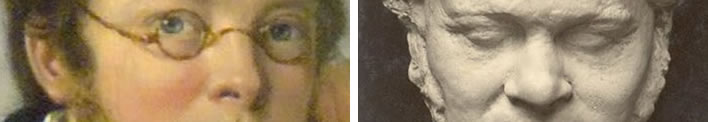

The gallery tells us that the painting was done in 1827, Schubert's penultimate year on earth. This is around the time that a death/life mask of Schubert was created, which provides us with the perfect standard for judging the Schubertness of the sitter.

The mask gives us an accurate representation of Schubert's physiognomy. How do we know that it is accurate? Because it was so accurate that Moritz von Schwind, when he came to draw the now famous Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun in 1868, used the mask, of which he had a copy, as the model for the profile image of Schubert sitting at the piano. Schwind certainly knew what his old friend Schubert's face looked like and his use of the mask as an aide-memoire is a validation of its accuracy.

Here we go.

When we compare the two heads as a whole, it is difficult to imagine that the same human being is behind them both. Is this painting supposed to be of Schubert? Really?

In desperation we might pick out the odd feature that appears similar – the sideburns or the curly hair, for example – but these slight similarities are outweighed by all the differences. We can only say at this point, before going any further, that if this really is a portrait of Schubert, it is a terrible likeness. It looks nothing like Schubert.

We could just stop here and get on with something useful, but let's go the extra mile and look at some details.

Consider the forehead, hairline and eyebrows.

Schubert's forehead was noticeably block-like and relatively high, nothing like the smoothly rounded, slightly sloping forehead in the painting. The rectangular form of Schubert's forehead is emphasised by the receding parts of the hairline. There is no trace of this in the painting.

Schubert's eyebrows formed a relatively straight horizontal line; those of the painting are closer to crescents, without the prominent eyebrow ridge we see in the mask.

In the region of the eyes and the nose the two images are substantially different. Schubert's nose was broad and flat; the nose in the painting is just a nose – without any interest or defining characteristics at all.

A closer look at the eyeline reveals clearly the massive brows and relatively deep eye-sockets on the mask. In comparison, the eyes in the painting are soft and featureless, with shallow eye-sockets.

Spectacles

Just wearing spectacles in the 1820s doesn't make someone Franz Schubert. There were plenty of people who wore them. In an optician's shop today the customer can choose from thousands of differing designs and materials; in Schubert's time the most common material was some type of metal, meaning that there was little opportunity for varying the design.

Here are the spectacles that Schubert was wearing in 1828 around the time of his death:

We see these spectacles (or ones with a very similar design) being worn by Schubert in two portraits of him by Josef Teltscher:

The left image was drawn in 1826, the right one in 1827. The shape of the frame, the hinges and above all the striking double arch over the bridge of the nose all correspond with the physical artefact we know today.

A drawing of Schubert done by Leopold Kupelwieser in 1821 (left) shows the oval frames we often associate with Schubert, although the bridge over the nose is simpler than the later version. Even so, these cannot be said to be the same spectacles that we see in Melegh's painting (above).

We cannot say in honesty that either of these types, the early or the later, corresponds to the round, horn-rimmed pair with the simple bridge worn by the subject of the painting.

The crucial role played by the presence of spectacles in leading people to see Schubert where Schubert is not to be seen is easily demonstrated. Would we be having this discussion at all if Melegh had painted this man?

Lower face

The area around Schubert's lower nose, his mouth and his chin provides us with some of the clearest characteristics of his appearance.

Even allowing for the slightly differing viewing angles between the two images, we can still say that there is nothing in the painting that represents Schubert's face: the nose is small and pert, the lips are narrow and pursed, the chin is merely a gesture – where is the chin-dimple, that Schubert trademark which no portraitist would overlook?

We repeat: if this was supposed to be a portrait of Schubert, it was a terrible one.

Tobacco addiction

Seeing a cigar-smoking Schubert is a bit of a shock, particularly with a stylish cigar case which matches his jacket and trousers. It is true he was a tobacco addict of the first chop, but plebeian prejudice has always imagined him to be primarily a pipe-smoker, as were many others in his circle.

As a former smoker, your author is quite clear that in the deep horrors of a nicotine deficit a true addict will stuff anything in his mouth and set fire to it – even, in extremis, filter cigarettes.

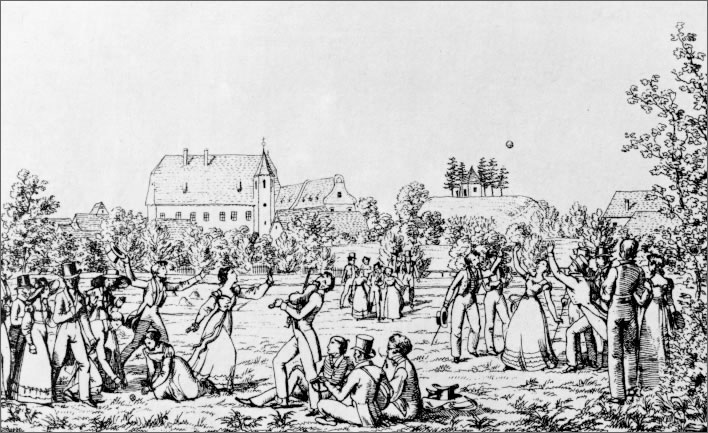

There are a few anecdotes in the Schubert biography where pipe-smoking is explicitly mentioned; Schubert is also shown smoking a pipe in Kupelwieser's illustration Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg. We might reasonably conclude that the pipe was the preferred form for Schubert to obtain his nicotine fix.

Pipe smoking would also appeal to Schubert because it was the most economical way of consuming tobacco. Unlike cigars (cigarettes were almost unknown in Schubert's time), which also required more manufacturing steps, all the tobacco in a pipe bowl was consumed and worked its magic. His smoking career certainly suffered no damage when, after his return from his first stay with the Esterházys in Zseliz in 1818, he moved in with his friend Johann Mayrhofer in the third floor of House 420 in the Wipplinger Strasse. For two years there they were tenants of the widow Anna Sanssouci, who was a tobacco dealer.

That said, the last page of the manuscript of Gesang der Geister über den Wassern, D 714, comes to us with a hole burned in it that suggests an unsupervised cigar (see Ernst Hilmar, Brille 10). However, your author can recall numerous examples of substantial damage to furniture and fittings as a result of the animated use of a pipe. Conclusion: pipe smoking is really only for the calm and the sober.

Standing back

At first glance the painting calls forth a simple and immediate conclusion from the observer: How bizarre!

This conclusion arises firstly from the odd structure of the painting – or rather, the apparent lack of any structure designed to reinforce the message of the image:

The elements of the picture are scattered over the canvas without any immediately obvious composition. True, the face of the sitter seems to be close to the horizontal and vertical golden sections of the painting, but the dominance of the two large 'windows' in the background of the painting slices up the top half of the painting into two separate panels.

Where is this?

The 'windows' are really arches through which we see a rather greyed-out landscape. This 'mountainous landscape of the environs of Vienna' corresponds with a view of the Leopoldsberg (425 m) with the striking twin towers of the Kirche am Leopoldsberg through the right aperture and the Kahlenberg (484 m) through the left. The standpoint would appear to be somewhere between Kahlenbergerdorf and Nussdorf, looking towards the north-northwest and would be well-known to any Viennese resident.

Since the arches are not glazed or framed we imagine the standpoint to be a verandah or terrace of a restaurant, possible one of the countless Heurige in this locality. It's difficult at this low resolution to be sure, but it looks as though the shoots creeping up the sides of the openings are vines, which would point more strongly towards a Heuriger as the current location. Our Viennese readers will surely know more.

The 'this is Schubert' faction will now be hyperventilating at the realisation that the location for this scene is only about five crow-kilometres from the tribal lands of the Schubert clan: Himmelpfortgrund, Lichtental and Rossau. Well, that's true, but in the summer thousands of Viennese went there to drink the local battery acid and amuse themselves in the vinyards.

But… but… what about Hoffmann von Fallersleben's account of a meeting with Schubert (and 'his girl') in a Heuriger in Grinzing – in exactly this area – on 15 August 1827? [Dok 444]

1827! Exactly the date of Melegh's painting! Answer me that, then! The guy in the painting was obviously on the pull in his chick-magnet mustard suit – there can be no other explanation!

In Vienna, in August, the nobility were away on their country estates. The members of the servant class were going about their daily duties, as they did all year round – windows were being cleaned, shirts were being washed, boots polished – but anyone who had some freedom and a little bit of money made their way out of the stinking, dusty cloaca of the city to the surrounding countryside. One of the most popular destinations was the wine growing area at the foot of the north-east part of the Vienna Woods, easily reached on foot or by carriage from the city.

We don't need to project Schubert into this painting. We see a man, looking very natty in his mustard-yellow suit, sitting on the covered verandah of a Heuriger. Why must this be Schubert?

Paraphernalia plus dog

There is a busy area in the bottom lefthand quarter of the composition. In the bottom righthand quarter a dog is the star attraction. The sloping posture of the man does unify the lower half of the painting somewhat.

In comparison with the other quarters, the bottom lefthand quarter is cluttered with paraphernalia – so cluttered that they fall off the lefthand side of the picture, leaving us with the irritation of part of a hat, part of a scarf, part of a stool, part of a table and part of a stick. On the table there is a coffee service, a half-eaten(!) gipfel/croissant and a cigar case with three cigarillos. The fourth cigarillo is being held in the subject's beringed right hand.

The light source for the painting seems to be off to the left. The shadows are quite deep, which is bit unsettling, since the two apertures at the back, despite their size, contribute no light at all.

Telling the tale

Leaving the question of the identity of the subject to one side for a moment, let's compose the narrative of this painting.

In establishing this narrative the two large apertures at the back play a key role. They tell the informed (=Viennese) viewer that the location of the scene is in a Heuriger (vines around the edges) in the wine-growing area beneath the Leopoldberg and the Kahlenberg.

The cloudy sky above the hills suggests that the weather is unstable; the soft-focus greyness of the countryside beneath also suggests that it is raining or it has just rained. This explains why so little light in coming in through those apertures. In contrast, light – albeit slightly diffused – is streaming in from the west, indicating that this is the afternoon. To the west the rain has passed and the sun is emerging.

We now realise why these apertures take up so much of the real estate of the painting: they set the place and the time of the painting and set out the background for the remaining narrative.

We can now see that the man in the picture is not simply taking a coffee break – the weather context suggests that he was on a walk, but has been forced to take shelter from the rain shower. We might assume that he was walking with the dog we see at the bottom right, but this assumption is not necessary. We must assume that the half-eaten gipfel is there to give the dog something to focus on, thus producing a bit of narrative tension in this otherwise relatively static picture. The dog's bared teeth certainly create narrative tension – but then, your author also bares his teeth at men in mustard-yellow suits. This is clearly a dog with taste.

Clothes maketh the man

As the Hungarian National Gallery pointed out, the clothing of the subject is that of someone quite prosperous – 'a classical member of the middle-class, the Viennese citizen humbly enjoying the joys of life'. Schubert never attained the status of a 'Viennese citizen' and certainly never became a 'middle-class individual', but we shall let those things pass. When Schubert died on 19 November 1828 he left behind according to Deutsch [Dok 558]:

- 3 cloth jackets

- 3 overcoats

- 10 pairs of trousers

- 9 waistcoats

- 1 hat

- 2 pairs of boots and 5 pairs of shoes

- 4 shirts

- 9 neckerchiefs etc.

- 13 pairs of socks

Schubert was not a hermit – he was a public performer and had to appear respectably dressed. He was present at the Schubertiaden, at balls, parties and concerts, among them occasionally some very elevated ones.

As far as the quantity of items is concerned, we should remember that washing machines had not yet been invented (at that time their precursors were called 'women') and a respectable person would need a number of items just to have something clean to put on. Kupelwieser's various 'Atzenbrugg' illustrations show us that, even as a young man, Schubert was a careful dresser to the extent his means allowed.

It is true that '10 pairs of trousers' and '9 waistcoats' leave some scope for the imagination, but it seems highly unlikely that what Schubert left behind was the wardrobe of a man who takes a dog for a walk wearing a bright mustard-yellow suit, a red silken(?) neckerchief, a substantial overcoat, a silk, olive-coloured(!) top hat, olive or grey leather gloves, a mustard-yellow outer scarf and a fine cane.

Schubert seemingly left behind no rings, no cigar case and no cane, although the absence of these in the listing might be due to the venality of his family, who had no interest in inflating his worth to the Viennese authorities.

Furthermore, no one who wrote an eyewitness account of Schubert ever even hinted at such dandyism. In all the accounts we have of him he is portrayed without exception as punctiliously dressed in public, as a modest, unassuming character, happy with anonymity, certainly not the self-satisfied, 'look-at-me' personality we see in Melegh's painting.

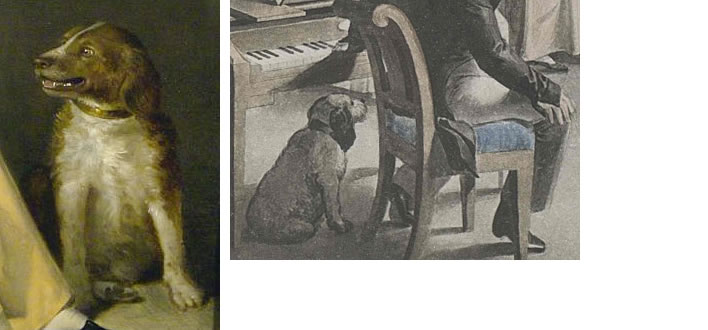

The faithful Drago

We have no record of Schubert taking dogs for a walk. He was a frequent walker, but we never read of him having a dog as a companion.

As far as anyone knows he never owned a dog in his nomadic life, nor did any members of his family indulge themselves in such luxuries. It is safe to say that, had he owned a dog, we would have heard about it from someone.

The only dog that was ever associated with Schubert was Kupelwieser's dog, Drago, and then only because the dog is shown in the vicinity of Schubert in Kupelwieser's illustration for the Gesellschaftsspiel der Schubertianer in Atzenbrugg in 1821. Why, in 1827, he is portrayed taking Kupelwieser's dog for a walk is just one of the many mysteries Melegh's painting holds for us.

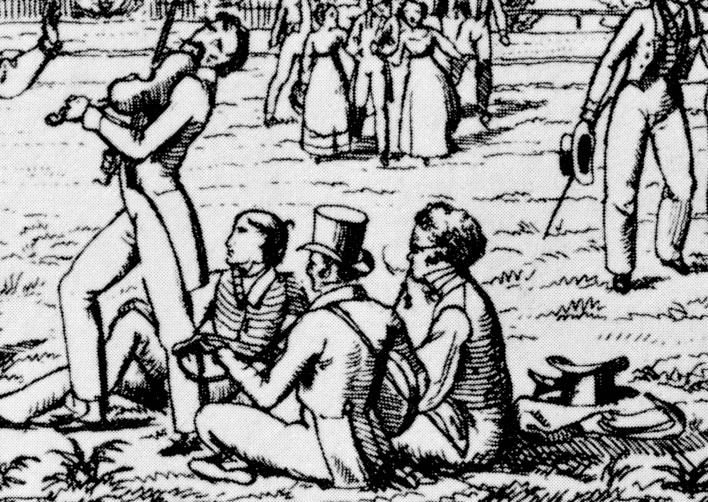

Leopold Kupelwieser (1796–1862), Gesellschaftsspiel der Schubertianer in Atzenbrugg, 1821. Drawing and watercolour. Image: Wien Museum.

Left: the dog from Melegh's painting. Right: Leopold Kupelwieser's dog 'Drago' watching attentively the charade for the word 'Rheinfall', at this moment illustrating the 'Fall of Man'. Since there was never as far as we know a 'Fall of Dog', Drago is understandably looking puzzled. Humans! Crazy people!

We can safely assume that Kupelwieser, seemingly a dog-lover, represented his Drago in his correct markings and colouring. A leopard never changes its spots, nor does a dog change its markings, so we can state unequivocally that the dog in Melegh's painting is not Drago. Unless, that is, Melegh is as bad at painting dogs as he is composers.

For completeness we should note that we are all assuming that the dog in Melegh's painting has some relationship to the human. There is, however, a possibility that the dog has been introduced by the painter merely to create the narrative tension of eyeing up the gipfel. That seems a rather far-fetched idea, but in this bizarre painting anything seems possible.

However, once the suggestion has been made that the dog in Melegh's painting was Drago there is now no looking back for the Hungarian National Gallery:

This picture, set in an atmospheric environment, shows Viennese composer Franz Schubert sitting on a porch. His dog, Drago, is sitting at his knees. How close do you think the relationship between dog and owner is? The composer is depicted during breakfast time. Take a careful look and observe what is on the table.

Generations of Hungarian children will grow up thinking that Franz Schubert was a well-heeled, dog-owning dandy. Let's be grateful for small mercies – it could be worse, though perhaps not in Hungary.

Ágnes Vayer-Zibolen: finding Schubert

As the basis for its attribution of the subject as Schubert, the Hungarian National Gallery calls on a 1986 paper written by the art historian Ágnes Vayer-Zibolen (1919-1999). The version used here is the German version available on JSTOR (paywall). The Hungarian version of the paper is available free to download as a PDF from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Ars Hungarica.

Our sympathies have to be extended to any Hungarian in whatever field who was trying to muddle along in the dismal years of the Communist regime in Hungary. The bad situation in the early days got worse over the next forty years until the final collapse came in 1989.

The 1986 paper of Ágnes Vayer-Zibolen on the identification of the sitter in Melegh's portrait displays all the limitations which faced the Hungarian academic in those days. She was primarily an art historian, not a Schubert specialist. The latter will search through her paper and be astonished at its meagre referencing of Schubert's life: no source works such as Otto Deutsch's blockbusters, merely a couple of secondary books 'about' Schubert.

Her task is unenviable: she has not much more information about the painter than she does about the sitter. Gábor von Melegh (1801-1832) died young (31, the same age as Schubert) and few surviving works can be attributed to him. His destiny was near oblivion.

Gábor von Melegh

He was born in Vršac, now peacefully in Serbia, but at that time one of those places on the eastern edge of the Habsburg empire which suffered almost continuous turmoil – anyone who wants to specify who ruled that region has to be very precise about the year in question, so frequent were the changes.

Ágnes gives Vršac as his birthplace, the Hungarian National Gallery gives 'Versec', which it adds is a town 'in Temes County (today: Timiș County in Romania)'. As far as I can ascertain there is no town or village in Timiș County called Versec or anything like it. The Hungarian language Wikipedia stub agrees with Ágnes and gives 'Versec' (=Vršac). Who knows? Who cares?

Opinion seems to have settled upon 1801 as his birthdate, but over the date of his death there is utter confusion. Ágnes gives 5 April 1832 and cites the relevant Totenbeschau document from the Vienna archive:

April 1832, on the 5th, Melegh Gabriel von, Academic Historical Painter, married, born in Versec in Hungary. [Resident at] Stadt 483. [Died of] tuberculosis, 31 years old.

April 1832, Am 5. Melegg Gabriel von, Akad. Historienmaler, verehlicht, in Verschetz in Ung. geb. Stadt 483. an der Lungenschwindzucht. 31. J. …. [Agnes 403n.]

The Hungarian National Gallery, however, follows the general opinion that Melegh died in 1835 'Gábor Melegh Versec [Vršac], 1801 – Trieste, 1835' (in a swimming accident), except on its other piece about the painting from which we are quoting, The Biedermeier and Franz Schubert’s portrait, where it agrees with the dates given by Ágnes – 'Gábor Melegh (1801–1832)' – before seemingly going wrong on the place of birth.

The citation of the documentary record by Ágnes is powerful evidence and we must believe her and not the wiseacres of the Hungarian art business, who are all busy copying off each other. She mentions the canard about Melegh's supposed drowning in Trieste in 1835 as being an error, but the staff of the Hungarian National Gallery who cite her paper for its supposed evidence about Franz Schubert don't seem to have read the other boring bits. [Agnes 404.]

What is going on here? Six paragraphs and we still haven't managed to establish the two essential data points for Melegh's existence. The desperate obscurity of the 'great Hungarian painter', that's what is going on.

We have a lot of sympathy with the modern desire of Hungarians to exhume their heroes from the ashes of history. Those ashes are deep: Hungary has been under someone or other's jackboot since the Middle Ages. If Melegh is going to be seen as a 'great Hungarian painter' there is a lot of shovelling that still has to be done.

Let's just put our heads down, carry on and pretend we know something.

According to Ágnes, Melegh enrolled in the Academy of Art in Vienna in 1817. After a view years there he moved back to Vršac and attempted to make a living there. However, in 1823 he returned to Vienna and would spend the rest of his short life there. Vienna, the capital of the empire, was the great magnet for an artist, the centre of all things, the place where the money was.

So far, so unknown – apart from these dates we know nothing about Melegh. He seems to have orbited around the Academy until 1829.

Ágnes accepts that there is a 'complete lack' of evidence that this is a portrait of Schubert, despite the fact that the figure 'displays a similarity to Schubert'. [Agnes 405]

In from the cold

The painting first emerges from the darkness at an auction in January 1919. The auction company, Wawra, described it as follows:

The composer Franz Schubert taking a refreshment break on a terrace. He is wearing a black overcoat, yellow jacked and trousers. Next to him on a table there is a tea service, an a chair his kerchief and hat, at his feet a dog. From the terrace there is a view to the Kahlenberg and Leopoldsberg, oil on wood, signed and dated 1837.

Auf einer Terasse sitzt der Komponist Franz Schubert bei der Jause. Er ist in schwarzen Rock, gelbe Weste und Hose gekleidet. Neben ihm auf dem Tisch das Teegeschirr, auf einem Sessel Schnupftuch und Hut, zu seinen Füssen ein Hund. Von der Terasse Ausblick auf den Kahlenberg und Leopoldsberg, öl, Holz, signiert und datiert 1837.

The incorrect date seems to have been a misreading or a misspelling of the date written on the painting, '1827'. Ágnes regrets that the seller of the painting chose to remain anonymous, which, given the political and economic turbulence of the times in Europe, should surprise no one. Nevertheless, it does mean that the painting comes with no provenance before 1919 – around ninety years of void.

Knowing the early provenance of the painting would have helped us enormously. It would have answered that key question in all artistic endeavour: who paid? Genre painters would use their knowledge of what might fetch a good price in choosing their subjects. Melegh's effort does not seem to be a genre painting – the single sitter is just too important.

Generally speaking, portrait painters did not pick up a brush until someone commissioned a painting for an agreed sum. Most of Kupelwieser's portraits of the Schubert circle seem to have been done out of friendship and/or possibly just to keep his hand in during his young days. There may have been artists who knocked off a portrait for fun, but unless they were independently wealthy, they were the ones who went hungry. It is reasonable to assume that someone commissioned this work from Melegh. If only we knew who that was.

An art dealer from Budapest bought the painting then sold it a few weeks later to the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. We have seen before in a previous Whac-A-Mole on a alleged painting of Schubert, that attaching the name of the now renowned composer Franz Schubert to a piece can work wonders for the sale price. To his credit, Elek Petrovics, the then General Director of the museum, put a question mark behind the attribution of the subject as Schubert and in his evaluation of the painting wrote that the painting presented 'a sitting man (allegedly the composer Schubert)' [Agnes 406 'stellt einen sitzenden Mann (angeblich den Komponisten Schubert)'].

In 1923 the painting was recorded in the inventory of the gallery without any mention of Schubert at all. In the middle of a list of the iconography of the painting we find merely 'a man with spectacles' [Agnes 407 'ein Mann mit einer Brille'].

In the years after that, the painting became simply a Männliches Bildnis, 'Portrait of a Man'. Those such as Ágnes Vayer-Zibolen, who really want to see Schubert in Melegh's painting, find this a shame; those such as your author, who think the subject is not Schubert, take this to be careful scholarship.

Unfortunately, Ágnes goes on to characterise what she imagines as the perversity of not recognising the subject of the portrait as Schubert as being evidence of some kind of conspiracy theory:

When so many errors, miswritings and forgetfulness accumulate, and when this picture is the only full figure representative portrait of Schubert in his beloved environment, with his characteristic, passionate qualities, set in a sunny harmony, we cannot exclude the mere suspicion of hidden intentions. The errors have been absorbed in the general consciousness and when the statements in the catalogue of the [auction company] Wawra and the physical traits of the subject are insufficient evidence that Gábor von Melegh painted a portrait of Franz Schubert, then we have to call to our aid the logic of circumstantial evidence.

Wenn um ein Gemälde sich so viele Irrtümer, Verschreibungen und Vergessenheiten anhäuften, und wenn dieses Bild das einzige, ganzfigurige, repräsentative Porträt Schuberts ist, in seiner geliebten Umgebung, mit seinen charakteristischen leidenschaftlichen Eigenschaften, in einer sonnigen Harmonie erscheinend, so können wir umso eher den blassen Verdacht einer verborgenen Absicht nicht ausschließen. Die Irrtümer haben sich aber hartnäckig in das allgemeine Bewußtsein eingesaugt, und wenn die Behauptung des Katalogs der Firma Wawra, und die konstitutionelle Ähnlichkeit des dargestellten nicht genügten zu beweisen, daß Gábor von Melegh Franz Schubert gekannt und porträtiert hat, müssen wir auch die Logik der indirekten Beweise zur Hilfe rufen.

[Agnes 408]

Ágnes has been chugging along nicely so far, but has now derailed completely. Her problem is, of course, that she really, really wants this to be a portrait of Schubert. The good researcher tries to maintain an open mind – Ágnes is now parti pris for her hypothesis, so that if there is not the slightest direct evidence then the case must be made by circumstantial evidence, what she calls die Logik der indirekten Beweise 'the logic of indirect evidence'. Everything she looks at now will go to 'prove' in some way that the sitter in Melegh's painting is Franz Schubert.

That she is already willing to accept as evidence what some auctioneer writes in a catalogue nearly a century of darkness after the creation of the painting is unfortunate. Add this to her own skewed interpretation of the iconography of the painting as relating incontestably to Schubert – well, the way from now on is going to be steep and downhill.

You are who you know

In order to spare the reader pages and pages of her 'circumstantial evidence' we shall summarise it:

Main proposition: During his time in Vienna, Melegh knew some people, some of whom may have known someone who knew Schubert. [Agnes 409-413]

A key intermediary was (Bonifaz) Thugut Heinrich (or Heinrich Thugut). He's a poor choice for an intermediary since we know less about him than we do about Melegh. Yet according to Ágnes he accompanied Schubert on visits to Linz, Gmunden and Salzburg – which comes as a surprise, since his name is only known to Schubert research as the artist supposedly – supposedly – responsible for three chalk drawings of the Fröhlich Sisters.

Since we know as good as nothing else about him, his supposed association with Schubert gets us no further. Having set up Heinrich as an important figure in the Schubert circles she now has difficulty bringing the shadowy figure of Melegh into contact with the even shadowier figure of Heinrich. [Agnes 416-417]

Having run out of rope with the Lloyd-George-knew-my-father theme, we now reach the nadir of Ágnes' efforts to bring Schubert and Melegh together, for she now tells us that Melegh was not just a Lebensdauergenosse, 'a life-long comrade' of Schubert's (which hyperbole comes as a bit of a surprise to Schubertians) but also lived in the Viennese Innere Stadt (which comes as no surprise at all to anyone, considering the number of people who lived there).

Did you know, for example, that Schubert's room in Schober's apartment in Tuchlauben was only a few streets away from Melegh's apartment Am Bergel? Not only that, but the Gasthaus zur ungarischen Krone, where the members of the Schubert circle (?) used to gather every evening(!), was only a 'few houses away' from Melegh's apartment!

The Gasthaus zur ungarischen Krone does indeed pop up a few times (here and here, for example) in the Schubert biography, mainly in the years 1823-1824, but it hardly occupies the central place in the life of the 'Schubert circle' that is assigned to it by Ágnes.

Ágnes herds the individual spooks of this phantasmagoria together to form a whole:

As we shall see from Melegh's work, the painter, the creator of lithographic and miniature portraits of the aristocracy and the intelligentsia, had walked the same streets, met his artist colleagues, in the same years in which Schubert lived there. In the Austrian capital of the twenties it would have been completely impossible that two artists, who moved in the same circles within such narrow spatial confines, did not know each other.

Wie wir aus dem Oeuvre Melegh’s sehen werden, hat der Maler, als Schöpfer der Lithographie- und Miniaturenporträts der Aristokratie und derselben Intelligenz, in denselben Straßen verkehrt, dieselben Malerfreunde getroffen, in denselben Jahren wo und wann Schubert dort lebte. In der österreichischen Hauptstadt der zwanziger Jahre wäre es ganz unmöglich gewesen, daß zwei Künstler, die im selben Kreis verkehrten, in einem so engem Gebiet, einander nicht gekannt hätten.

[Agnes 422]

In order to dispel this particular spook, Schubert fans only have to recall Otto Deutsch's estimate that the nomadic Schubert had 17 different addresses during his lifetime. [Dok 591]

Finally – oh, please let this be the end! – Leopold Kupelwieser, Schubert's friend, and Melegh both studied at the Vienna Art Academy. Kupelwieser did the famous watercolour scene of the charade in Atzenbrugg in which he illustrated his dog, Drago.

It cannot be an accident that in the Schubert portrait of Gábor von Melegh the same dog is sitting, quite at ease, as though next to an intimate acquaintance, its gaze directed here longingly at the remainder of the breakfast, not at the composer.

Wir können es auch nicht dem Zufall zuschreiben, daß auf dem Schubert-Porträt des Gábor von Melegh derselbe Hund sitzt, ziemlich bequemlich, wie neben einem intimen Bekannten, sein Blick richtet sich hier sehnsüchtig auf die Reste des Frühstücks, nicht auf den Komponisten.[Agnes 426]

As shown above, the dog in Atzenbrugg and the one in Melegh's painting are not 'the same dog' – not even nearly.

Did you know that one of the few surviving works of Melegh's is a portrait of Count Vinzenz Esterházy de Galántha (1787-1835) done in 1831? He was, of course, a first cousin of Graf János Károly (Johann-Karl) Esterházy de Galántha (1775-1834) who hosted Schubert on his Zseliz estate in 1818 and 1824 – so it must be Schubert in Melegh's painting. QED. [Agnes 427]

Through misty eyes

After the pages of Lloyd-George-knew-my-father argumentation on the mean streets of the Vienna Innere Stadt, Ágnes returns to discuss the iconography of the painting – but can she be looking at the same picture we see?

The painter did not just know the composer, he knew him well. Everything on him and about him is in character. His hair was not so thick and curly as in earlier years, but since his illness softer and thinner. His spectacles are also in character, he wore them at all times, they can be seen on show in the house of his birth in Vienna. The black coffee and the cigar are indispensable and are mentioned in all the written descriptions of him. On the coffee service in the picture – it seems – there is a blurred monogram: the first letter is an 'F', followed by three more, perhaps 'Sch', shaped into a decorative motive, or can one read the ornament as letters? Schubert – as his acquaintances tell us, liked beautiful underwear, and when necessary could appear carefully and elegantly dressed. The top hat next to him on the stool was also a piece of clothing that he always wore.

Der Maler hat den Komponisten nicht nur gekannt, sondern wohl gekannt. Alles auf ihm und um ihn ist charakteristisch. Sein Haar war in den letzten Jahren nicht mehr so dicht und kraus, wie ehemals, seit seiner Krankheit nur gewellt und spärlicher. Seine Brille ist auch charakteristisch, er trug sie immer, sie ist noch heute in seinem Geburtshaus ausgestellt. Der schwarze Kaffee und die Zigarre sind unerläßlich und kommen in allen, über ihn verfaßten Beschreibungen vor. Auf dem Service des Bildes — scheint es — befindet sich ein verwischtes Monogramm: der erste Buchstabe ist ein »F«, dem folgen noch drei, vielleicht »Sch«, in ein Ziermotiv umgeformt, oder kann man das Ornament als Buchstaben lesen? Schubert — wie seine Bekannten schrieben, hat auch die schöne Leibwäsche gern gehabt, und falls es notwendig war, konnte er sorgfältig gekleidet und elegant erscheinen. Der Zylinder neben ihm auf dem Stuhl, war auch ein Stück, das er immer trug.

[Agnes 429]

The resolution of the image of the painting published by the Hungarian National Gallery is too low to allow us to examine the monogram. We would point out, though, that there is no point a painter putting a monogram related to the sitter into a painting unless the viewer can read it. Sometimes porcelain decoration is just that – porcelain decoration. It would anyway be an odd thing to do to put the monogram of the sitter on the coffee cups of the restaurant.

We hope that readers who spent some time looking at our analysis of the physiognomy of our subject and the iconography of the painting as a whole will also conclude that not only is Ágnes Vayer-Zibolen clutching at straws in trying to forge an association between the famous Schubert and the almost unknown Melegh, she is looking at the painting through the distorting lens of her own wishful thinking.

Left: Schubert by Josef Teltscher, 1826. Right: 'Schubert' by Gábor Melegh, 1827.

It is particularly amusing that in her paper she reproduces the 1826 drawing done by Teltscher as an example of the similarity between known Schubert portraits and Melegh's 'Schubert'. To an objective observer, the faces in the Teltscher portraits and the face in the Melegh portrait are quite different in many respects (but particularly eyebrows, nose, lips and chin). These are not images of the same person. [Agnes 429]

Conclusion

In Melegh's painting

- the hair, forehead, eyebrows, eyes, nose, lips and chin are not those of Schubert;

- the foppish clothes, rings and rich accoutrements are quite out of character for Schubert;

- the spectacles are not those of Schubert;

- the dog is not Kupelwieser's Drago, Schubert did not have a dog;

- Schubert is not commonly thought of as a cigar smoker.

In other words, the subject in Gábor Melegh's painting is not – repeat, not – Franz Schubert.

We cannot of course rule out that Melegh's portrait is an imaginative, almost surreal treatment of some vision of Schubert in Melegh's head. But if this were to be the case the painting loses all value for us: we are really interested in factual, figurative representations of the composer that tell us something about him, not some fantastic reconstruction out of Melegh's odd brain.

Update 21.01.2020

It is surely one of the great blessings for Schubert scholarship that the composer had a number of pictorial artists among his circle of friends. Leopold Kupelwieser, Moritz von Schwind come immediately to mind, but we must not forget that Franz von Schober also had artistic talent. Apart from numerous portraits of the Schubert, we have the illustrations they did for the country house parties the Schubertianer held at Atzenbrugg. From these we glean many hints about them all.

Clothes

In the present article we mentioned Schubert's dress sense. We suggested that when in public Schubert always took care with his appearance. In the following illustration by Leopold Kupelwieser in 1820 we see Schubert and Kupelwieser at the far left of the composition.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Landpartie der Schubertianer von Atzenbrugg nach Aumühl, 1820, watercolour. Image: From a lithographic print, original is in the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien.

Kupelwieser, the racy young artist, is wearing a frock coat which he has topped off with a jaunty cap. Schubert, on the other hand, is wearing the full rig of frock coat, waistcoat, voluminous cravat (as far as we can see this) and top hat. Kupelwieser, who was a tall man, has been kind to Schubert, who was a short man, by levelling up the height difference somewhat.

Smoking

In another illustration of a ball game of the Schubertianer at Atzenbrugg we have the only known image of Schubert smoking. Here he is sitting on the ground next to Michael Vogl(?), contentedly smoking a pipe and watching the goings on of the friends.

Top, full scene: Die Schubertianer beim Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg c. 1820, a collaborative work by Franz von Schober, who drew the scene, Moritz von Schwind, who drew the figures, and Ludwig Mohn, who did the etching.

Bottom, detail: Schubert smoking a pipe, Michael Vogl(?) playing the guitar and Moritz von Schwind(?), reclining. Some think Schwind is the one playing the violin. Schubert – wild thing! – has taken the liberty of removing his frock coat and top hat. Images: Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Wien.

Update 16.02.2020

More than a month ago, shortly after completing this article, we sent the Hungarian National Gallery a polite and friendly email asking them, in the light of the analysis in this article, to review their assertion that the subject of this painting is Franz Schubert.

Silence. No acknowledgment. No response. The texts on the relevant pages of its website, here and here, remain unchanged. Even the erroneous place and date of Melegh's death remain uncorrected.

Perhaps they just don't read their emails.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!