In the Neolithic Age

Richard Law, UTC 2025-09-30 12:06 Updated on UTC 2026-02-15

Update 05.10.2025 – Revision

Update 31.12.2025 – Apropos Neolithic cannibalism

Update 15.02.2026 – A Mesolithic Taffy?

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature. In its encomium the Committee gave its reasons as:

…in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1907.

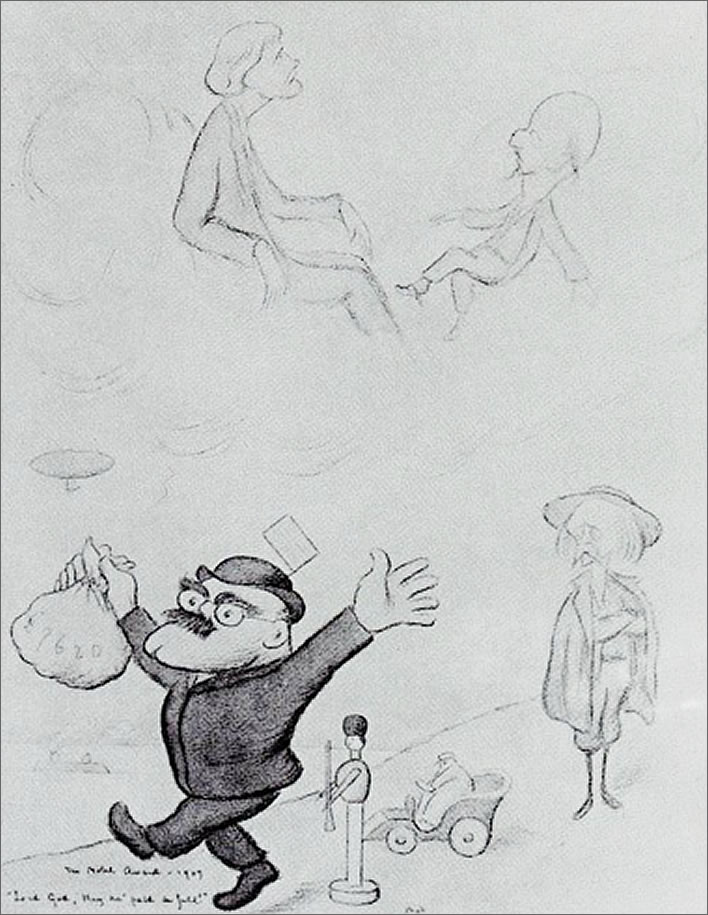

A caricature by Max Beerbohm (1872-1956), not an admirer of Kipling, on the occasion of Kipling's being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907. Kipling is shown bottom left, triumphantly carrying his swag bag of the prize-money ('£9620'). Looking on, in an aggrieved pose bottom right, is the sartorially challenged Hall Caine, a humourless drudge now rightly forgotten but a prolific and best-selling author of the time. Caine was not nominated, but two British nominees for that year's prize, Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909, left) and George Meredith (1828-1909, right) are depicted floating above, indifferent to earthly happenings.

The prize brought with it not just fame but the sort of money that penniless scribblers could only dream about: in 1907 each Nobel Prize award was worth 138'796 Swedish krona (kr/SEK). Beerbohm wrote the sterling amount on the bag, £9'620. Today's equivalent would be around £1'009'316 according to the Bank of England.

In the febrile world of scribblers – then as now – there were always people ready to criticise the bright young writer Rudyard Kipling, who had risen to fame and fortune remarkably quickly. Kipling never attacked his fellow scribes. He laid out his feelings on this point in his 1895 poem, In the Neolithic Age. It revealed Kipling at his best: witty, entertaining, manly. The poem is not obscure, but modern readers may need a bit of help getting over the line, so I have added some notes. Here we go.

In the Neolithic Age (1895)

In the Neolithic Age savage warfare did I wage

For food and fame and woolly horses’ pelt;

I was singer to my clan in that dim, red Dawn of Man,

And I sang of all we fought and feared and felt.

Yea, I sang as now I sing, when the Prehistoric spring

Made the piled Biscayan ice-pack split and shove;

And the troll and gnome and dwerg, and the Gods of Cliff and Berg

Were about me and beneath me and above.

The Neolithic (in Europe), a.k.a. the New Stone Age is currently considered to have lasted from c. 7000 BC to c. 2000 BC. It was marked by the emergence of settled farming cultures and the associated development of sophisticated kitchenware – that is, it was the moment in which wimmin took over the world.

We shouldn't overthink Kipling's use of the term Neolithic, the break up of 'Biscayan ice-pack' would seem to be something that happened at the end of the last interglacial, which occurred about 10'000 BC, at the end of the Paleolithic Age. It's called 'poetic licence'. | dwerg: dwarf. | Cliff and Berg: Note how precisely this statement (me/here, cliff/down, berg/up) is reflected in the line which follows it: about me and beneath me and above.

But a rival of Solutré, told the tribe my style was outré —

’Neath a tomahawk, of diorite, he fell.

And I left my views on Art, barbed and tanged, below the heart

Of a mammothistic etcher at Grenelle.

The archeological findings at Solutré (now the commune of Solutré-Pouilly, in Burgundy) typify the Solutrean culture of the Upper Paleolithic (20'000 BC to 15'000 BC), a Cro-Magnon type which came just before the Neolithic. [See the 'Neolithic Notes' below for more details.] There is an interesting museum there. The thirsty can pick up a few bottles of Pouilly-fuissé while you are exploring – just check that the contents match the labels, you know what I mean. | outré: 'Beyond the bounds of what is usual or considered correct and proper; unusual, peculiar; eccentric, unorthodox; extreme.' OED. | tomahawk: the North American Indian weapon we have all heard about. | diorite: a very hard and tough rock which, though difficult to work, makes good stone tools. | barbed and tanged: 'tanged' implies that the arrowhead has points or barbs on it to allow it to stick in the victim. This could also be the meaning of 'barbed' ('To furnish (an arrow, hook, etc.) with barbs'), but this would simply duplicate the meaning. One not very satisfactory solution would be to read 'barbed' as 'feathered'. Reader djc has made a good suggestion, namely that the arrowhead is 'barbed' on its front edges in the conventional sense and has also a 'tang', in this case a projection at the rear of the arrowhead which allows the head to be attached to the shaft of the arrow. | mammothistic: Kipling has taken the suffix 'istic' – atheism-atheist-atheistic, idealism-idealist-idealistic, etc. – and constructed a new word using it that we can take to mean 'mammoth-venerating'. | Grenelle: This refers to the Grenelle basin, on the northwest of Paris, now urbanised completely within the 15th arrondissement. This was an important paleological location in the 19th century. [See the 'Neolithic Notes' below for more details.]

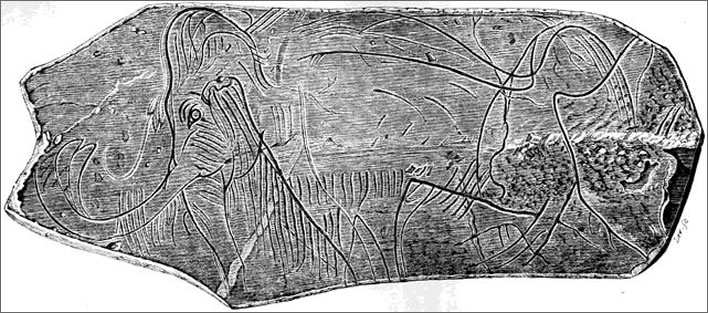

Woolly Mammoth engraved on an ivory plate found in the cave of La Madelaine, Périgord. Image: From Charles Lyell, Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (also The Antiquity of Man), 1873.

Mammoth engraving on a large piece of mammoth ivory found during the excavation of the rock-dwelling of La Madeleine, near Les Eyzies by Edward Lartet in May 1864. The two images are clearly different but also in many ways very alike; we might even think that the same artist etched them both – or perhaps even different artists – using formulaic elements Image: Charles Lyell, ibid.

Then I stripped them, scalp from skull, and my hunting dogs fed full,

And their teeth I threaded neatly on a thong;

And I wiped my mouth and said, “It is well that they are dead,

“For I know my work is right and theirs was wrong.”

But my Totem saw the shame; from his ridgepole-shrine he came,

And he told me in a vision of the night:—

“There are nine and sixty ways of constructing tribal lays,

“And every single one of them is right!”

Totem: Originally a concept applied to some indigenous North American peoples but also more widely applied to numerous other peoples with similar beliefs. The totem is usually a representation of an animal or some natural object, which in turn represents a spirit that watches over the tribe, clan or even the individual. The spirit manifests itself in the form of the animal or object which represents it. Such a totemic animal is never hunted, killed or eaten.

Then the silence closed upon me till They put new clothing on me

Of whiter, weaker flesh and bone more frail;

And I stepped beneath Time’s finger, once again a tribal singer,

And a minor poet certified by Traill.

They: the gods. | a minor poet certified by Traill: Henry Duff Traill (1842-1900) was a British writer and journalist. Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) had been Poet Laureate since the death of his predecessor, Wordsworth, in 1850. By 1892 it was clear that Tennyson would not last much longer (he died in October) and Prime Minister Gladstone and the literary establishment began the process of selecting a successor for this prestigious position. Trail published an assessment of the fifty leading poets of the day, finding them all more or less wanting. As an afterthought he added Kipling's name as the fifty-first on the list, with apologies but no enthusiasm, thus 'certifying' Kipling as a 'minor poet'.

The satire here is very Kiplingesque, witty yet without rancour, despite Traill's public de haut en bas denigration of a fellow writer. After a few years of wrangling, the title was awarded in 1896 to that dim bulb, Alfred Austin (1835-1913). Kipling wasn't interested: he was a citizen of the world (as would be explicitly recognised by the Nobel Prize Committee in 1907, who in their encomium even quoted his line 'And what should they know of England who only England know?' from his poem The English Flag). Already in 1892 he had made his home in America with his new wife.

Still they skirmish to and fro, men my messmates on the snow,

When we headed off the aurochs turn for turn;

When the rich Allobrogenses never kept amanuenses,

And our only plots were piled in lakes at Berne.

aurochs is the name of a very large wild ox (not to be confused with the bison) that roamed Europe until the mid-eighteenth-century, when the species became extinct. The phrase 'headed off the aurochs turn for turn' alludes (I think) to the hunting technique for such large, fast and dangerous beasts, in which they would be herded ('headed off … turn for turn', aided by the aforementioned 'hunting dogs') into a natural corral where they could be slaughtered more efficiently. The legend of wild horses being driven off the top of the Rock of Solutré now seems incorrect, though there are places such as narrow gaps between large rocks which were almost certainly used to funnel prey for slaughter. | Allobrogenses is Kipling's poetic remodelling of the standard term Allobroges, the name of a Celtic tribe of ancient Gaul (France) which settled around what is now Lake Geneva and the Rhône valley, making them congruent with the builders of the lake dwellings in Berne. We now know that lake dwellings built above ground on piles existed in many suitable places in Switzerland, most significantly around the Lake of Zurich. The dwellings were not built in the lake, as is usually imagined, but on suitable shores at the edge of the lake. A moment's reflection will make it obvious that even a modern construction company would find driving piles into an underwater lake bed not a simple task, certainly well beyond the capabilities of Neolithic men with stone hammers. The Allobroges certainly didn't need amanuenses to write for them, and their plots were the territory upon which their dwellings rested on wooden piles.

Your author's inner pedant adds: Kipling's creation of the word Allobrogenses (being an analogue of words such as Albigenses) although not used in modern scholarship, is justifiable poetic licence. The '-genses/sis' ending is the classical Latin suffix, 'of/coming from the [aforementioned place]'. For example, the Albigenses heretics were originally from Albi, in France. In the present case, there was no place called Allobro from which the Allobrogenses came. That said, 'allobro' comes from an ancient root 'allo' + 'brog', meaning 'other/foreign + country' – to the previous inhabitants the newcomers were simply 'foreigners' in Gaulish. Strictly speaking therefore, Kipling was not wrong to use this term, just swimming against the philological Zeitgeist. So the next time you are taking to social media or even to the streets, tell the cops that you are protesting against all the bloody Allobrogenses.

Still a cultured Christian age sees us scuffle, squeak, and rage,

Still we pinch and slap and jabber, scratch and dirk;

Still we let our business slide — as we dropped the half-dressed hide —

To show a fellow-savage how to work.

scuffle, squeak, and rage … pinch and slap and jabber, scratch and dirk the sort of unmanly argument one might expect from a tribe of apes, Neolithic humans or modern aesthetes. To 'dirk' = stab (with a dirk).

Still the world is wondrous large, — seven seas from marge to marge —

And it holds a vast of various kinds of man;

And the wildest dreams of Kew are the facts of Khatmandhu,

And the crimes of Clapham chaste in Martaban.

a vast, used as a noun, is a dialect word meaning 'a very great number or amount'. | Martaban, now called Mottama, is the name of a town in Burma/Myanmar that in Kipling's time was part of British Lower Burma.

Here’s my wisdom for your use, as I learned it when the moose

And the reindeer roared where Paris roars to-night:—

“There are nine and sixty ways of constructing tribal lays,

“And—every—single—one—of—them—is—right!”

roared … roars: a wonderful construction, the two halves of which cleverly align the Neolithic Age with the Modern, thus concluding the metaphor which has run through the whole poem. Any poet would be proud of startling the attentive reader with such a bold construction. Unfortunately, in or sometime before the final version of the risibly titled Inclusive Edition, 1885-1932 (1933) of Kipling's poetry, 'roared' was changed into 'roamed', quite destroying Kipling's fine construction. Being kind, I suspect a typo, 'roa*ed-roa*ed' and sloppy proofreading. The error was propagated into the even more risibly titled Definitive Edition (1940) and is now the de facto official version. 'Roared-roars' had survived through all the many editions of Kipling's verse up to just before his death in 1936, only to be mutilated by the poetically cloth-eared as soon as he was gone. As a result we can expect 'roamed-roars' to creep into circulation, particularly now with the Kipling Society propagating it in their text of the poem, despite all my protests. At the poetic level, no reader of sound mind could prefer 'roamed' to 'roared'. Yes, yes, I know: 'Still we pinch and slap and jabber, scratch and dirk'…

Neolithic Notes

Among the scribbling fraternity Kipling distinguishes himself by a curiosity and thirst for knowledge that transcended all categories and pigeon-holes. In a previous piece I quoted Harold Macmillan's opinion of him:

He was still the supreme journalist, always interested in the master of any craft or the hero of an exciting adventure.

Much travelled at a time when travelling was not as easy as it is now, his open-eyed lust for knowledge reminds us of Odysseus, 'of many counsels, knower of many men and places'. Mark Twain wrote of him: 'Between us, we cover all knowledge; he covers all that can be known and I cover the rest'.

For a period from around the middle of the 1890s until the beginning of the new century, amongst his many other interests, he appears to have developed an interest in what we might call the ascent of Early Man – geological, paleological and archeological studies, which may have been triggered by his move to Vermont in 1892. Being naturally inquisitive, he burrowed into the prehistory of his adopted country. He seems to have merged Native American and European prehistory: our readers may remember his description of his daughter Josephine/Effie in her Neolithic persona Taffy, set in the landscape of prehistoric West Sussex, but wearing a reindeer cloak and mocassins and sending him smoke signals – all Native American features (c. 1900-1903). His poems 'In the Neolithic Age', 'The King' (1894) and 'The Story of Ung' (1896); the two canonical Just So stories, 'How the First Letter Was Written' and 'How the Alphabet Was Made', plus the non-canonical story 'The Tabu Tale', stories all written between 1897 and 1903, all show the results of his paleological interests.

Paleology and the related sciences have made tremendous progress since the end of the nineteenth century. Kipling's understanding of the ascent of early Man is rooted in his times, so we shouldn't try to discuss his ideas in modern terms, correcting his misunderstandings. Let's stick to what was known at the end of the nineteenth century.

The paleological search at the time was for what became known as the missing link. Darwin and Huxley had convinced us of the evolutionary processes of Nature. We have the world of apes, the higher primates, and we have the world of humans. What evolutionary chain linked them?

Fossil human bones were discovered in 1856 in Germany in the valley (thal/tal) of the river Düssel in North Rhine-Westphalia (near Düsseldorf). By a process too convoluted to describe here, the valley had been named after a local celebrity, Joachim Neander. These Neanderthals were clearly more ape than human, but their discovery was a step forward, nevertheless. The search was on for the post-Neanderthals, and as digging expanded, more and more fossil remains came to light: bony bits of this and that, parts of skulls, some nearly intact.

Fossil remains of humans were usually given names according to the place of their discovery: Cannstadt Man (1835), from Cannstadt, near Stuttgart in Germany; Cro-Magnon Man (1859), first discovered near the village of Les Eyzies in the Vézère valley in the southwest of France and then in numerous places such as the valley of the Somme in northwest France and at Grenelle near Paris.

'Cro' is a word from Occitane (old Provençal) meaning 'trench, cave or cavity'; Magnon was the name of the landowner. Timewasters such as your author are always pleased to stumble upon language relics such as 'cro'. It is an ancient word first found in Celtic/Pre-Roman krosu-, then in Latin *crosus, with the meaning 'hollow' or 'cave' – thus giving us 'the cave of Magnon'. It is distributed widely thoughout the Romance languages: southern France, Liguria, Piemont, Lombardy and Romansh-speaking Graubünden in Switzerland. It is widespread in the various Romansh idioms of today – in the idiom of my village, Sursilvan, it has come to be used for hollow, protective things: la crosa the empty shell of a snail, an eggshell, the shell of a nut etc.

The fossils were measured and categorised, skull shapes and volumes were recorded. Paths of descent started to emerge. Not only bones, but also cultural artefacts, differing stratum by stratum as the excavation progressed: weapons such as knives, spear tips and arrowheads; engravings on bone and ivory; various utensils, adornments and so on. Much scholarly heat was generated in the categorisation of these objects.

At Grenelle, the excavations down through the alluvial strata marked a crucial point in this voyage of discovery. The dig became effectively a journey through time: what became known as Grenelle-Furfooz Man was the youngest at a depth of five to eight feet; then came Cro-Magnon Man at ten to thirteen feet and then finally Cannstadt Man [=Neanderthal] below that.

Solutré (strictly speaking, the Rock of Solutré) appears to have been a site only used for hunting – a prehistoric hunting lodge as it were. As such it has been a rich source of many artefacts of tools and weapons. No human remains have yet been found there.

The domestic pendant of Solutré is the neighbouring Rock of Vergisson, where the remains of Cro-Magnon type humans and domestic artefacts have been found. While the men sat around in the cave of Solutré messing about with their weapons, retailing stories of hunts past and planning hunts to come, waiting for someone to invent the cultivation of tobacco, the wimmin hung out in the cave of Vergisson, cooking the dinner and talking about whatever wimmin talk about, then and now. The term Solutrean is used to describe a tool-working style, and not a particular type of human.

Grenelle-Furfooz Man got part of his name from the Caverne de la Naulette near Furfooz in the valley of the Lesse, Belgium. The location is a complete domestic settlement, with an inhabited cave and a burial cave. The people were compact in size, five feet four to five feet six inches tall. Their skill in working stone was not of the highest level, but they made whatever they could out of reindeer antler.

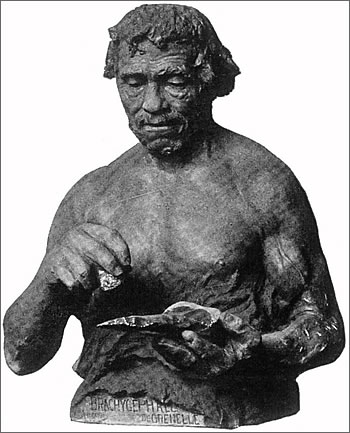

A 'mammothistic etcher at Grenelle': Photograph of a reconstruction of a broad-headed Grenelle-Furfooz Man by the Belgian artist Louis Mascré (1871-1929). The image was part of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum's "Pre-history Gallery" in the 1930s. This is not a 'reconstruction' in any accepted sense of the word. In this case the sculptor goes into a bar-tabac and finds someone in the gloom with a broadish head who is prepared to take his shirt off and sit still for a few hours for 50 Fr. It's not hard. Image: ©Wellcome Collection.

It was a long time after the first discoveries that relatively reliable dating techniques clarified the chronology. None of this was known while Kipling was writing, of course – in his time the expert's dating was just a higher form of guesswork mainly based on stratigraphy. Kipling's fine phrase in which 'the Prehistoric spring / Made the piled Biscayan ice-pack split and shove' refers to the end of the last ice age. As everyone knows, the ice sheet covering the northern hemisphere didn't just disappear in toto, it withdrew northwards and mountainwards and many of the ancestors of Man followed the retreating cold and their retreating prey with it. The end effect is that the timing of all these periods is fuzzy with an effective uncertainty of thousands of years.

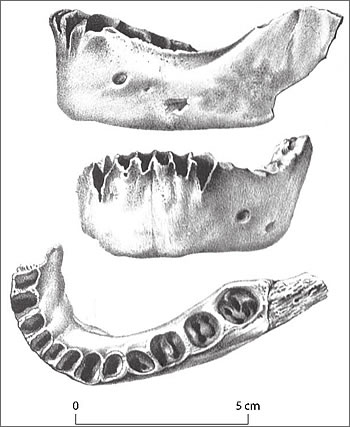

As we know from his Just So story 'How the Alphabet was Made', Kipling paid some attention to the necklaces of the Neolithic. In the Neolithic Age contains a scene of making a necklace from your victim's teeth. Thus it is suggestive that the sturdy jawbone belonging to the putative Grenelle-Furfooz Man that was excavated in 1866 in the Caverne de la Naulette has no teeth. Since the missing teeth were never found we can only assume that the Neolithic-Kipling had paid them a visit: 'their teeth I threaded neatly on a thong'.

The toothless Naulette jawbone.

'I wiped my mouth'. In human bones from this period there is plenty of evidence of murderous cut marks, this does not necessarily indicate cannibalism, but it would be surprising if cannibalism, especially used as a way to absorb the power of the slain enemy, was not practised.

The Popular Science Monthly

What was the trigger for Kiplings interest in the prehistoric ages? What was the source of his information? I don't know. Someone may have explored this at sometime; if they have it is unknown to me. I might, however, lay my neck on the block with a speculation for which I have no evidence whatsoever.

At some point after Kipling moved to the USA in 1892 I suspect he subscribed to The Popular Science Monthly, which had been founded in 1872, another of those magazines of that time having the worthy aim of bringing the new learning to the educated layman. It was essentially an aggregator of articles from elsewhere – in no sense a criticism, since it brought to the readers the scientific Zeitgeist, if you will, curated from sources to which the normal person, far from the great libraries and colleges, would not have access. In a time before radio, movies and television, magazines such as this helped to fill in the longueurs.

A modern reader will be struck by the lack of dumbing down for the 'educated laymen': articles were reproduced tels quels, often from renowned or highly credentialled authors. I would be surprised if Rudyard, that intellectual magpie, after his arrival in the New World, endlessly curious about all things, didn't subscribe for the journal's 'mixed pickles' content. In his rural retreat in Vermont he probably valued the stimulation.

For us at the moment, our minds on Rudyard's interest in the Neolithic age, the idea of The Popular Science Monthly as a source of information for him is attractive, particularly because of its extensive coverage of the then very hot topics of geology, paleology and the ancestry of Man. At that period almost every scientific subject was exploding with new discoveries. Kipling doesn't seem to have been attracted to the new physics, chemistry or biology – he was far more interested, it seems, in the human-facing subjects which were those hot topics of the time. Every month, The Popular Science Monthly may have brought him seeds for his fertile imagination. I am not saying that this was his only source or even his main source, just that the magazine's paleological articles appear to align with his interests at the time.

After long searching recently I have found no smoking gun – a phrase, some particular terminology – that would link the magazine to Kipling's writings. He was too good a writer to need to copy other people's formulations. There are shared ideas and facts aplenty, but Kipling could have got these from anywhere.

However, one particular article is quite suggestive as a possible stimulant for the context of 'In the Neolithic Age': 'Fossil Man', authored by John G. Rothermel in the The Popular Science Monthly, Vol. 44, March 1894 ('A lecture delivered May 12, 1893, in the Popular Course before the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia.').

The first item of interest is the date of the appearance of the article: 'March 1894'. Kipling had been in Vermont since 1892; the poem 'In the Neolithic Age' is dated 1895. Rothermel's article covers most of the items we encounter in the poem, particularly the search for descendants of Neanderthal Man. Broadening out our view, in Volume 44 alone we find several pieces that would probably interest the author of 'In the Neolithic Age': 'How Old Is the Earth', 'Evolution in Professor Huxley', 'The Position of Geology', 'Fossil Man', 'Evolution I/II', 'The Ice Age and its Work I/II', 'Glacial Period'.

The second item of interest is the French setting of 'In the Neolithic Age': Solutré in Burgundy, Grenelle in Paris, the Bay of Biscay, the roaring moose and reindeer of Paris. The only detour away from France is to Berne in Switzerland, at a similar latitude. Modern paleologists see the Neolithic as being a global phenomenon, the early roots of research in Europe being buried under data from distant, non-European cultures. Modern readers may find this French focus odd, but Rudyard was working with what he had got. At the end of the nineteenth century the research focus was Europe and the articles in The Popular Science Monthly as well as the text of Kipling's poem of course reflect this French environment.

We have to imagine that early Man overwintered, as it were, the last Ice Age, which was at its height around 40'000 BC, in the warmer, near-equatorial zones of the Earth. Nothing lives on an ice sheet itself – where vegetation cannot grow there can be no life – but at its edges there was a cold tundra landscape with plentiful water to which a number of large mammals had adapted – the large size of their bodies allowed them to conserve warmth much better than small mammals could. As the ice sheet slowly retreated over thousands of years, its tundra fringe moved with it. It was in this fringe that the early hunter-gatherers flourished or eked out an existence. They and their Mesolithic/Neolithic culture moved northward with the big game in the tundra fringe, leaving behind the settled farming culture which had developed in the temperate zones behind the fringe.

So that, when the Kiplings abandoned Vermont after the death of Josephine and returned to Britain (1899), Rudyard concluded his dalliance with prehistory by imagining his dead daughter and her family as Neolithics in West Sussex, not France, the fringe having moved further north.

Update 05.10.2025

General revision of the article.

Update 31.12.2025

A silly, scary title which contradicts the text in a very confused article about Neolithic cannibalism in a Belgian cave, an issue we mentioned here. The main points:

Analysis of bones found in a Belgian cave where cannibalism was found to have taken place has revealed the victims were children and young women. Scientists said the identity of the cannibals is unknown […]

The Goyet caves contain the most significant collection of Neanderthal remains found in Northern Europe Image: Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences

The Goyet cave in central Belgium, discovered in 2016, contains Neanderthal bones from around 45,000 years ago and some have signs of cut marks on them, a telltale sign of cannibalism. The women and children that were eaten may have been kidnapped in raids by the cannibals, researchers said, or body parts could have been hacked off and carried back to the attackers’ home cave for ease of transport. It is also possible the body parts, including those of a Neanderthal infant and a child as young as six, were cooked before being eaten, scientists suggested. […]

Update 15.02.2026

The skeleton of a girl of about three years old (too young for Taffy) dating from the Mesolithic period has been discovered in a narrow burial-cave, Heaning Wood Bone Cave in Great Urswick, Cumbria.

Her remains date from around 11'000 years ago, making them the earliest remains ever found in Northern England. Readers of the present article will remember the discussion of the northward retreat of the ice sheet and the civilisations who survived on its margins. An account of the discovery was in The Telegraph. The open access research paper on the subject is here.

It is striking that this cave appears to have been used as a burial site for at least eight individuals ranging from the Early Mesolithic, the Early Neolithic and right down to the Early Bronze Age.

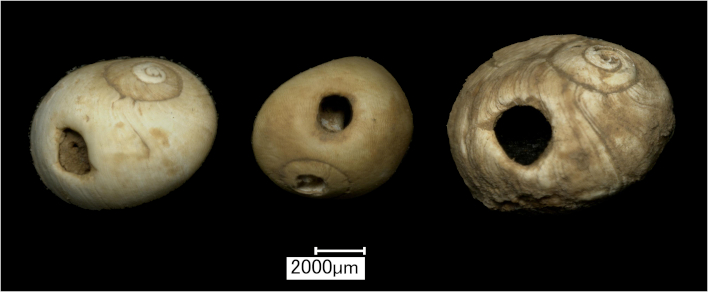

The reports were marred for me by the researchers' confident waffle to the media about the social organization and the deep thoughts of our Mesolithic ancestors. But, overlooking that blemish, I found the account of the five perforated periwinkle shell beads which were apparently buried with the child mightily touching.

Perforated shell beads from Heaning Wood Bone Cave. Even today the wide tidal seashore of Morecambe Bay is a favoured spot for gathering shellfish. Image: Warburton et al..

Such artefacts were produced by not inconsiderable labour, so that leaving them with the body of the three year-old, perhaps still round her neck, represents a significant gesture of grief and hope that even we debased moderns can comprehend. At the risk of sounding like an over-excited archaeologist, perhaps such objects were the gates between worlds. Who knows?

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!