Christian Schubart – The road to doom

Richard Law, UTC 2016-02-07 16:53

The author of the poem Die Forelle, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739-1791), was an interesting and complex man who led an eventful life during remarkable historical times in Europe. His biography makes a fascinating tale, but it is a tale that is difficult to understand without some background from the times. Let's daub this background in a broad-brush paragraph or two before we move on to the man himself.

The historical context

From the early Middle Ages (say 800 AD) right up until the middle of the nineteenth century and arguably in some respects beyond, continental Europe was a feudal construction. The First World War and the great political, social and industrial revolutions that preceded it finally obliterated feudalism in Europe.

Feudalism – what does that mean? Using our broadest brush we can say that it means a society organized around three so-called 'estates'. The classifications vary, but we can say that for our purposes the First Estate was the organized church, the Second Estate the aristocracy, the Third Estate consisted of farmers and established citizens, people with trades and positions, numerically by far the largest of the three Estates. The Second Estate, the aristocracy, was bound by complicated rules of obligations and inherited ownership.

But by far the largest number of people belonged to a group that was so disorganised and menial that it wasn't even counted as an estate: the serfs working on the land or in (cottage) industries, the poor, the widowed and orphaned, the sick and the injured and war wounded. We say 'the largest number of people', but this is a number that is difficult to quantify, so far beneath the radar were these people. Who was counting?

Even the supposedly 'socially caring' revolutionary theorists of the nineteenth century, particularly Marx and Engels, were utterly contemptuous of these unfortunates, calling them the Lumpenproletariat, the people in rags who were as ignorant and stupid as the rags they wore. It is one of the great lies of history that the communist revolutionaries cared anything at all for the lowest orders of society. They didn't, but that is another story.

What makes the feudal organization in Europe particularly interesting for us in our present context – indeed the context of the life of every individual of the time – is its rigidity, its lack of social mobility. For men born into the Third Estate or lower it was extraordinarily difficult to move upwards out of the status of your birth. Women hardly counted in this scheme. For academically able children a route through education might be available if the money and inclination were there to pay for schooling. Even so, higher education was for much of the time not even open to young men from the Third Estate: it was not appropriate to their state. The concept of social mobility, of people rising through social groups, did not exist.

What's a poor boy to do?

Generally speaking, administrative positions within the European state bureaucracies were only accessible to members of the Second Estate. The First Estate, the organized church, offered some social mobility, but only up to a point. The upper echelons of the churches were generally occupied by aristocrats from the Second Estate. Somewhat surprisingly, social mobility was easier in the Catholic Church than in the Protestant Churches. Because Catholic clergy were (notionally) celibate, new blood from outside was always required, whereas Protestant positions tended to be handed down from father to son.

Given this situation, what can a clever, ambitious boy in the Third Estate do to make his way in the world? A boy who doesn't just want to carry on doing what his father does?

Franz Schubert's father and uncle had the great good fortune to have a pious, clever and hardworking peasant father who sent them off the land to get a solid Jesuit education, from where they both found themselves in the right place at the right time to take advantage of the demand for teachers in the rapidly expanding primary school education sector of Empress Maria Theresia's Austria. Decades of grinding drudgery and subservience to religious authority brought them both to respectibility. Schubert's father, by the time he died, had even aquired some property and had been made a free citizen of Vienna.

Franz Schubert's struggle to exist as a composer and artist outside the fabric of the feudal system would not have been possible if his uncle and his father had not made the jump from being the sons of a Moravian peasant through all those years of menial drudgery in the service of the state and the church. Two of his brothers also reconciled themselves to educational drudgery and made good careers for themselves, but Franz's talents meant he could never accept continuing the family tradition in education. He therefore lived an economically adventurous life, full of risks and setbacks.

Christian Schubart (there is a tradition of calling him Daniel, but he tells us that his family always used his first name, Christian) was the son of a lowly Protestant vicar. If we overlook for a moment the extreme personality traits that did so much to shape his life and which brought so much suffering down upon his head, we can see that his 'life situation' is very characteristic of many talented people of the time: they had to scratch out a living as best they could within these monolithic feudal blocks.

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, Schubart's Leben und Gesinnungen, Mäntler, Stuttgart, 1791, title page. MDZ online.

The die is cast

Christian Schubart was born in the small Swabian town of Obersontheim on 24 March 1739. This is really just a technicality, because within his first year the family moved to Aalen, a 'free imperial town', where his family would stay for the rest of their lives. His father was a Protestant vicar, which at that time involved, in addition to all the usual priestly tasks, playing the organ, singing, teaching in the school, ringing bells and many other menial tasks. It was a feature of towns and villages throughout Europe at the time, that the local vicar was the general factotum who had to perform as many tasks as possible for as little money as possible. As Schubart says

My father had struggled with the bitterest poverty since his youth; he could therefore expect no education beyond what Mother Nature had given him. [1][SLG I p. 3f.]

Schubart portrays his father as a cultivated man, despite his poverty and menial status, a man who himself had an exceptional feeling for the poor. Already we hear Christian's own bitterness at the limitations of the society of the time:

Had he not had to battle poverty and deprivation from his youth onwards, and were he not stuck in such a limited and restricted situation he would have been an important and famous man, for he had energy, courage, a German sensibility, had a natural taste in word and deed and a feeling for everything that was good, large, noble and beautiful. [2][SLG I p. 7.]

As the son of a vicar and schoolmaster Christian came into contact with the common people and counted himself as one of them in solidarity. He hinted at that 'German-ness' being the cause of many of his difficulties among the 'stiff people' (as Franz Schubert would later call them):

In this town in which honest simplicity had nourished modest cititzens for centuries – citizens with old German traditions, modest, hard-working, wild and strong like their oaks, despisers of foreign countries, defenders of their smocks, their dung-heaps and their thundering dialect – I grew up. This is where I received the impressions that would never be erased by the experiences of my later life. The usual manner of speaking in Aalen seems like truculent shouting in other towns and like mad ravings at court. [SLG I p. 9.]

We have already identified two themes that would play out in the Greek tragedy that would be Christian's life: firstly, his belief in the superiority of robust German culture over the effete French and Italian cultures that defined courtly life and secondly, his solidarity, following the model of his father, with the poor and dispossessed. In his patriotism he prefigured the German nationalism and the feelings of German identity that would shape the culture of the early nineteenth century. In his solidarity he prefigured the social revolutionaries of that time. As such he is not a minor figure, but a weathervane for the times in which he lived.

His parents, recognising his abilities, encouraged and developed his taste in music and literature. Biographers like to detect a lack of parental control, or perhaps an excess of parental indulgence, that would lead to the difficulties in his adult life. [3]

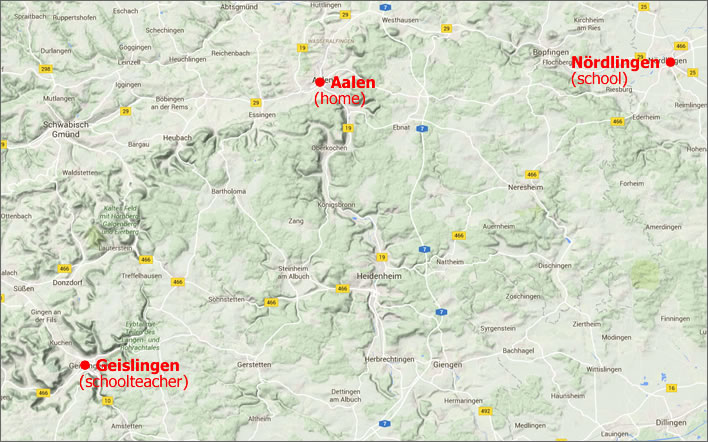

Locations of Schubart's youth in Swabia: Aalen (family home), Nördlingen (secondary school), Geislingen (first job, schoolteacher).

He lived in Aalen with his parents until 1753, when, fourteen years old, he was sent to the Lyceum in Nördlingen, another Protestant town in Swabia about 40km from Aalen. There followed three years of strange, but Schubart-typical contrasts. On the one hand he was encouraged to familiarise himself with the higher peaks of German literature, but on the other hand his enthusiasm for carousing with apprentice tradesmen, manual workers and the lower orders – a.k.a. the 'common people' – was given full rein.

The third characteristic in his Greek tragedy was therefore his populism, his preference for the people of the poorer classes. For those who wanted to get on, the times required an attitude that could seek and take the prince's pennies with good, preferably obsequious grace. Schubart might occasionally try that, but it was not in his nature, not in his nature at all.

After three years in Nördlingen he went on for two years more schooling in Nürnberg and then, in 1758 to the University of Erlangen, where he was to train as a vicar. With what we know of him already the idea of Christian Schubart as a vicar can only be called risible. He was in his nature incapable of orderly studies and fluttered from this subject to that. The only constant during this time was his raucous student life – I was about to write 'ending in' imprisonment for debt, but the imprisonment was more of a highpoint in a continuous process.

Tired of this useless drain on their meagre finances his parents recalled him to Aalen, where he hung around, doing this and that for about three years. If he couldn't take holy orders, what other path remained open to the boisterous, multi-talented young man?

The schoolteacher

The twenty-four year-old was now desperate for a job. He was deeply in love with Katherine, a girl from a well-to-do family in Aalen. Her family was set firmly against her marrying Schubart, who had no income, no prospects and no respectability – he was every father's nightmare, in fact. A job might certainly help. Finally, despite the car crash of his education so far, he managed to obtain in 1763 a teaching post in the small town of Geislingen.

The post in Geislingen had arisen when, a few years previously, the schoolmaster of the boys' school, a man called Röbelen, had been given permission to hire an assistant, paid for from his own pocket. Röbelen, then 50, was sickly and feeling his age. He needed some help with the 150 rowdy boys he had to teach. For this task he found a young man locally, who was not only willing to work for a pittance but who had also promised to marry one of Röbelen's two daughters. This arrangement was to last only a few years before the young man died in the autumn of 1763. The post was advertised as a continuation of this arrangement – although this time a daughter was no longer part of the deal.

The post was officially to be that of the schoolmaster's assistant. His predecessor had scraped by on starvation wages of 94 gulden a year, which had been paid by Röbelen out of the 400 gulden a year he received. There was therefore no incentive at all for Röbelen to be generous with his underling.

Running the school in Geislingen was a family business, in fact, since Röbelen's son, subordinate to his father, was in charge of the girls' school and received 300 gulden, which amount puts the assistant's wages into perspective. The only good thing to be said about the lowly job was that the assistant would assuredly take over the schoolmaster's post on his death – which seemed to be imminent: when Schubart wrote to his parents on 5 November he said that the elder Röbelen was so ill that he could scarcely be expected to live another eight days. Schubart clearly assumed that the underling's job would be a brief, temporary measure. As it turned out, despite all Schubart's expectations, Röbelen refused to die for another seven years, only dying the year after Schubart left Geislingen – how fate plays with us!

Hearing of the job, the young Schubart now made the first mistake which was to blight his life in Geislingen and set him on a crisis course for the rest of his life. He negotiated with the authorities and 'talked up' the job description. The lowly teaching assistant became a schoolmaster for the entire boys' school, the musical director for the town and the church, a music teacher in the school, the organist in the church as well the tutor for a small class in classical languages. Somehow, despite his unfinished studies, he also obtained his licence to preach and was thus required to give regular, paid sermons. The official titles of all these posts were quite modest but he seems to have inflated them for public consumption. How could Katharine’s parents refuse their daughter's hand now?

In his haste to festoon himself with titles, Schubart had overlooked or ignored the other side of the arrangement. His working day would be between nine and twelve hours long. Admittedly, he would now earn 200 gulden, with free accommodation, some extra payments and 'a manure heap' (a perk not to be sniffed at), but this would never be enough to support the Schubart manner of life. There were also a number duties that the schoolmaster's assistant was expected to carry out of which Schubart was either unaware or which, in his enthusiasm to get the job, he chose to overlook, duties that during his time in Geislingen would grow ever more more irksome.

Röbelen, father and particularly son, who had lost income and duties to Schubart, were not well disposed to the cuckoo in their nest, who came with a vaunting ambition and immense self-esteem that made him completely overqualified for the lowly post. Furthermore, schools in Protestant areas at that time were run by the church, meaning that Schubart, ambitious and talented, found himself at the bottom of a pile under the two Röbelens, and then above them a hierarchy of the people that Schubart hated above all: religious clerics.

The husband

He started the job, whatever its titles finally were, on 31st October 1763, having left Aalen with 'Katherine hanging on his horse'[4], both of them in tears. The first blow fell as soon as he accepted the post, for if Schubart's plan had been to impress Katharine’s parents with his new-found titles it didn't work. There would clearly be no marriage to Katherine, his first love. Schubart being Schubart, however, his heartbreak did not last long. Almost as soon as he started in Geislingen, as if the yoke that he had placed upon his own shoulders would not be enough, he now got married to a local girl, Helene Bühler.

Helene was the middle daughter of the Senior Customs Officer in Geislingen, Johann Georg Bühler. Accounts differ as to how Schubart met Helene, but whatever happened, no sooner had Schubart arrived in Geislingen than he paid a call on Bühler. More than a call, in fact, because he stayed all afternoon and all evening. Finally, as the clock struck midnight he stood up and announced to Bühler – the only one who had not by now gone to bed – that he would that day obtain a wife, namely his second daughter, Helene. Bühler pointed out that he was not a wealthy man and that Helene had an older sister, Magdalena, who was still to find a husband. Schubart insisted that he receive an answer that morning. Bühler consulted some relatives but the chance to marry off one of his daughters was not to be missed. Bühler gave Schubart his consent. He was bitterly to regret that decision.

Schubart asked for the consent of his own parents on 5 November, only five days after having arrived in Geislingen and six days after the weeping Katharine had been hanging on his horse. So great was his haste that the courier who brought the parents the letter had been instructed to wait for the answer. The wedding took place on 10 January 1764.

The bliss would be brief. Schubart the poet, journalist, musical prodigy, free spirit and man of the world had committed himself to long days of grinding duties for a pittance. He was left hardly any time to follow his real interests and every communication he had with the great men of letters of the day – Wieland and Klopstock – just made his awareness of his limited life more acute. He spent his days teaching rustics the elements of German, his wingèd horse stuck in a provincial backwater.

His first two years in Geislingen were the worst. The full extent of the labours that were now expected of him became clear to him. His belief in the enlightening power of education came up against the hard reality of large classes of unruly village boys in which the cane was never out of his hand. Parents complained about his teaching and even threatened him. The Röbelens missed no opportunity to criticise the new expensive cuckoo in their nest. Ground down by his remorseless duties for little reward, Schubart rapidly became depressed, disillusioned and angry at his lot.

Not made in heaven

Even worse, his hastily concocted marriage brought him no comfort, just the opposite, in fact. Helene – and her family and relatives in Geislingen – had no understanding of Schubart's intellectual ambitions or even, given the few days of courtship the pair had enjoyed, could they know anything of him at all.

She was a person of simple, deep piety and of orderly, economical ways, brought up in a family of restricted means with a provincial outlook. There is a tradition to this day in Germany of characterising Swabians as penny-pinching misers. Her father, a customs officer, was required to be sober and punctilious in his job and beyond reproach in his family life. Schubart, on the other hand, was a drunken reprobate with national ambitions who was constitutionally incapable of living within his means. As a result, the couple were permanently short of money and often confronted with final demands for payment.

Each book he bought and each evening spent in the alehouse was a cause of friction between the pair. Helene seems to have had little understanding for the tribulations of his post. His frustration and anger simmered inside him. There were bitter arguments: Helene was not the grey, downtrodden mouse we might imagine. She was a strong woman who deeply resented her husband's profligacy whilst she had a household to run on their very limited means. She was also carrying their son, who would be born just a little over a year after the wedding.

In the course of their heated arguments Schubart would even 'box her ears', as he put it. Her family was appalled at this marriage, so much so that, not much more than a year after the wedding and only three weeks after the first child's birth, Helene's father felt driven to write a long letter of complaint to Schubart's clerical superior, a letter he may have written in order to protect his own reputation and that of his family from the damage that his son-in-law was doing to it.

The kind of disreputable, base, vexatious, prodigal, self-destructive, irresponsible life led by my son-in-law, schoolteacher Schubart, and the mismanagement of his affairs, will be easily apparent from the following true account.

It is reported that Schubart indulges every day in roasts, meats and other fine foods, tea and coffee and always tobacco, even cheap, stinking tobacco. He always has an ale mug in front of him and keeps questionable company, neglecting his school duties. He rarely arrives at school on time and as a result everyone is complaining; … he gets drunk at every opportunity, increases his debts by buying unnecessary books, stores wine intended for his wife on the maternity bed in the cellar but drinks it up himself beforehand and cultivates, as is widely known, the vice of lying about people and slandering them.[5]

Schubart's inability to control either himself or his tongue would get him into trouble throughout his life; he was never be able to suffer the perceived indignities of his lot in silence. Although Bühler's dislike of his son-in-law was relentless and vengeful throughout Schubart's time in Geislingen, there is, however, no reason to doubt the essential parts of Bühler's account, written in flowing anger.

It is a well known and proven fact that his wife, who looks after the house without the help of a maid, a few days before giving birth was beaten so severely that she had black eyes on her maternity bed, and that he, two days before she gave birth, on the instigation of his brother went around neighbouring villages yelling and singing and afterwards threw his wife and her sister out of the house, even giving the latter bruises from a vicious beating and even, as a sign of his madness, throwing a spindle in the town moat.[6]

Schubart had no friend in the vicinity to calm or counsel him at this low point in his life. Perhaps his brother's presence was some help, but if we believe Bühler it seems to have just made things worse.

The family man

After the first two stormy years in Geislingen Schubart calmed down, which, given the constellation of factors against him, is much to his credit. His family life gained more purpose: four children arrived in quick succession. Their first child, Ludwig, was born in February 1765, in the middle of the worst of the turmoil. Their second child, Johann Jakob, arrived at the end of May, 1766 but only lived six weeks, dying of a sudden illness. Their daughter, Juliane, arrived in the middle of July 1767. Another daughter was stillborn in December of 1768. Schubart was, by all accounts, a devoted, even doting, father to the two children.

It is also to his credit that, despite his workload and ever-present poverty, he managed to keep to keep his intellectual and literary life going during these years, corresponding with the greats of the period, Wieland and Klopstock, and writing occasional pieces.

'Calmed down' in Schubartian psychology is only a relative concept. Certainly his womanising seems to have continued unabated: he regarded women as 'flowers on which every butterfly could flutter its wings', as he wrote later. There were many tears at home. Nor did Helene passively accept his infidelities. In 1768, the year that ended with the stillbirth of their daughter, she was fined for insulting in a fit of jealousy a woman whom she suspected of dallying with Schubart in the Rötelbad, a health spa just outside Geislingen, a popular destination for the well-to-do people of nearby Ulm. The convivial and witty Schubart was frequently called upon to preach and to minister to the souls of the guests there and, so it seems, added his own distractions to the pleasures of the baths, which were renowned for the treatment of 'female disorders'.

Helene's sense of propriety was constant and her ongoing resistance to Schubart's moments of drunken dissipation and debauchery was heroic, particularly given his violent temper. 'You were lovely, so lovely' she was to say to him much later as his death approached, but this man must have taxed her endurance. Drawing on her deep faith, she could only hope that God would sooner or later guide her husband onto the path of righteousness and that, true to Pietist tradition, that guidance would be brought to him by the Bible. What other means did she have to to curb the wild, volatile man she had married?.

My wife used to write quotations from the Bible on small slips of paper, leaving them in places where I would find them. I appeared to treat them with contempt at the time, but I kept them all in my heart and now in the dungeon they fall like flakes of fire on my soul. [SLG II p. 160.]

Schubart held out in Geislingen for six years. By the fifth year his life had become more orderly – another relative term in Schubartian psychology, since there were escapades right up to the last. But in six years in Geislingen his limit had been reached. Fame beckoned. In 1769 he took a further step on the downward path that would lead to his doom: he obtained a post in Ludwigsburg, the capital, better known to pious folk such as Helene Schubart as the 'Swabian Sodom'.

Sodom calling, 1769

In 1769 Schubart applied for the post of Organist and Music Director at the court of Duke Carl Eugen in Ludwigsburg. Helene Schubart was appalled at the prospect. She knew all too well by now the weakness of her husband before temptation: and what temptations he would face there! Carl Eugen's court was a byword for all manner of excess and immorality. She was not alone in her prescience: her father, Schubart's own relatives and friends, even his brother Jakob, who had not much longer to live, shook their heads at the prospect.

Schubart's last weeks in Geislingen were grim, the battles with his wife continual. On one occasion, after he had lost his temper and 'boxed her ears' yet again, Bühler forced his way into the house and took Helene and the children back home with him. His wife and children finally returned, but Bühler continued to make as much trouble for Schubart as he could. Vengeful as ever, he went so far as to request Schubart's arrest before he left.

Right up to the day before his departure, Helene pleaded tearfully with Schubart for him not to go to Ludwigsburg. There was some sort of a reconciliation, but the following day he left on his own. Schubart left Geislingen in the post-coach on 21 September 1769, after more than six eventful years there. According to him, a crowd of young people with tears in their eyes and bringing gifts for him saw him off, evidence, as he wrote later to a friend, that he could not have been as bad a teacher as his father-in-law had made him out to be. Bühler was not finished with his campaign against his son-in-law. He rode ahead of him and, arriving in Ludwigsburg before Schubart, delivered letters slandering his son-in-law's character and behaviour to Schubart's friends and supporters there.

Fortunately or unfortunately for Schubart the embittered Bühler's vicious act had no lasting effect. By good luck, Schubart had managed to obtain solid references from other sources and Bühler's slanders, at least for the moment, could be written off as the ranting of an angry father-in-law. Reconciliation with Helene followed: three weeks after his departure from Geislingen Schubart returned to collect his wife and family. A son was born in mid-April 1770, six months after they had arrived in Ludwigsburg. He died in December of the same year, barely seven months old, of smallpox, which all their children had had that autumn.

Forgotten roots

In Ludwigsburg Schubart played the organ and was responsible for the music played during the church services; he was a music teacher, composer, writer, poet, teacher of literature. He was a virtuoso and a brilliant performer. No wonder Carl Eugen had wanted this man at his court in Ludwigsburg.

Unfortunately for him – as Helene had foreseen – he became popular and celebrated in society, at the court, among the nobility, in the music and theatre worlds, even with the man in the street. His initial salary of 700 gulden per year – the Geislingen assistant teacher with 200 gulden and a manure heap is now but a distant memory – could not support this lifestyle. His pay was raised appropriately in autumn 1771.

Schubart being Schubart, he could mock the gilded fripperies of his new life and the affectation and ostentation that surrounded him. However, not so slowly but very surely he began to absorb its ways. In Ludwigsburg, he later noted, Paradise and Hell lay side by side and it was just as easy to live either a saintly or a degenerate life. The man who praised German simplicity and directness now chose degeneracy. Later, looking back on this time, he described his error thus:

I lived like an Italian and lost myself in the society of courtiers, officers and artists. [SLG I p. 143.]… Recklessness and thoughtlessness were the two demons that led me to ruin. [SLG I p. 152.]… Wine and women were the Scylla and Charybdis, that took turns to swirl me in their whirlpool. [SLG I p. 153.]… I became ever colder towards virtue and religion, read free thinkers, mockers of religion and morality and brothel keepers and, worst of all, passed on the poison that I sucked in. [SLG I p. 156.]

In August 1771 Helene went back to Geislingen to visit her family, returning to Ludwigsburg at the end of the month. Two months passed, two months in which Schubart's behaviour became ever more reprehensible to his pious, God-fearing wife. In December the crisis came to a head and Schubart in a drunken rage beat her. Once sober he was full of sorrow, begging for forgiveness, but shortly after, taking advantage of his absence, she fled to the family home in Geislingen, taking their children with her. It seems she had prepared in advance for this moment – the modern observer can only say: at last!

In a letter after Helene's departure Schubart wallows at first in self-pity: 'I deserve a lot, but not this', then grumbles at the inconsiderate woman whose horizon is so low that she prefers living among the peasants of Geislingen than the cultivated nobles of Ludwigsburg.

Helene returned to Ludwigsburg about three months later, sometime around the beginning of March 1772. She soon fell seriously ill and in the summer of that year her father came to fetch her back to be cared for in Geislingen.

The last straw, 1772

With or without the presence of his family, Schubart continued on his downward path. The piano lessons he gave were a continual opportunity to 'instruct' the fair sex in more than music. His escapades caused him to pick up a sexually transmitted disease, probably gonorrhoea, on at least two occasions, diseases which he promptly passed on to his wife. He had therefore good reasons for thinking that he might very well be the cause of the disease that had reduced her to a bag of bones. We can only imagine what black thoughts were going through her father's mind as he took his emaciated daughter back to Geislingen.

Schubart's stroll towards catastrophe continued. That spring his friend Böckh in Esslingen had been promoted to be Deacon in Nördlingen. For unknown reasons, the family's maid, Barbara Streicher, a girl from Aalen, where Schubart grew up, did not go with them. Instead she went to Ludwigsburg to help look after Schubart and the children whilst Helene was on her sickbed there.

With the departure of Helene and the children, Schubart, now 33 years old, seems to have extended the duties of the 21 year old girl to be a full marital replacement for Helene. Such a thing could not stay secret for long in Ludwigsburg. Rumours of it even reached Helene, lying seriously ill on her bed in Geislingen. Although the maid's references had been impeccable, Helene had never warmed to her and, knowing her husband all too well, gave credence immediately to the rumours. Jakobina, Schubart's sister, was sent via Geislingen to Ludwigsburg but could not save the situation. Helene rose from her sickbed and arrived in Ludwigsburg herself at the beginning of September, too late to do anything but just in time to witness the drama run its course.

Spezial[7] Zilling, Schubart's immediate superior, had not been well-disposed to Schubart from the time of his appointment, when Schubart had, in effect, been forced upon him as church organist by Duke Carl Eugen. Their characters were completely opposite: Schubart the wild hedonist, mocker of all pretension and authority; Zilling the puritan zealot, pompously overblown with the gravitas of his own office. As a result, their antipathy was mutual and deep. Since Schubart's arrival in Ludwigsburg, Zilling had missed no opportunity to take Schubart's every fault to task and now, at last, he had serious grounds for action.

On the basis of the rumours Schubart was arrested, charged with 'suspicious behaviour with a girl' and thrown into prison during the investigation. With two consenting adults and no witnesses the case could not be proved and Schubart was released shortly afterwards. Such immorality, although deeply shocking to Zilling and the Pietist church, was certainly no detriment to a career in Ludwigsburg: Schubart walked away from this brush with Zilling without serious damage. But his enemies were only waiting their moment, which Schubart, being Schubart, would inevitably give them.

He did so surprisingly quickly, seeming unchastened, even emboldened by his previous escape. In January of 1773 he had written a song satirising an 'important member of the court'. He followed this up with a parody of the Litany, the prayer sequence which Luther himself had held to be at the core of Christian faith, made even worse by the fact that Zilling, quite rightly, saw some of the persiflage as being directed at his person.

When Zilling got to hear of all this he excommunicated Schubart, who was ordered by ducal edict on 21 May 1773 to leave Ludwigsburg 'without fail'. The reasons given were his adultery with Barbara Streicher, admittedly unproven, and a scurrilous satire he had written and circulated. There can be no such thing as an excommunicated church organist. He had to go.

In this situation, the normal man would have put his affairs in order, gathered his family and left in an orderly fashion. The man we are dealing with is, however, Schubart. Commanded to leave Ludwigsburg 'without fail', he actually left the moment he received the edict, storming off with a few coins in his pocket and not even saying goodbye to his wife and family.

Abandoned, Helene stayed a little while in Ludwigsburg, treated as a beggar and exposed to the mockery of Schubart's enemies, before leaving to go back to Geislingen and her parents' house. Her situation would become even worse: when she arrived she found both her mother and her brother on their deathbeds, dying of typhus. She looked after them, in doing so contracting the disease herself, having no idea where her husband now was. She and her children would live in Geislingen for the next two years.

Augsburg, 1774: the journalist awakes

For Schubart there followed nearly a year of wandering from place to place in Germany, living on his wits as a performer and raconteur. He spent some time in Catholic Munich, where the stout, lifelong Protestant Schubart opportunistically almost converted to Catholicism. There was some talk of going to Stockholm, but this plan shattered after he got into a violently heated argument with a Catholic friar in a post coach. Enraged, Schubart impulsively got out of the coach in the middle of the journey and walked across the Lechfeld plain to the imperial city of Augsburg.

Suddenly, in Augsburg, a fog seemed to lift from Schubart's mind. He stayed at the hostel of the Guild of Weavers (weaving was the principal industry of Augsburg) and immediately found himself among his own sort of people: German craftsmen and tradesmen, citizens of a free imperial city, who would come to dine and drink in the tavern of the hostel. The Italianate peacocks of Ludwigsburg were just a bad memory.

Schubart, the virtuoso performer with music and with words soon found an eager and growing audience. Not only did he feel comfortable among these people, they made efforts to keep him in Augsburg for themselves. He felt welcome and wanted.

A bookseller in Augsburg, Konrad Stage, asked him to write a piece for publication. He first thought of writing a novel, but that would have required steady effort and unwavering dedication from him; Stage also wanted something more quickly. Schubart came upon the idea of writing a German Chronicle, a small magazine, a sheet of paper at first, which would appear twice a week and in which he would write… well, anything he felt like writing that would amuse, entertain and educate the German public. The first issue of the German Chronicle came out on the 31 March 1774, not even a month after Schubart had arrived in Augsburg. The news magazine was born and Christian Schubart was its progenitor.

It was something that matched his talents perfectly, the 35 year old who had lived a life of highs and lows, who had known the courts of princes and a number of their prisons, too; the German patriot, who had seen the enervating French and Italian influence on German life; the free spirit, who had experienced the repression of absolutist princelings and clerical zealots first hand. And, just as important for him, in this project he was his own master and had no need to rely on the goodwill of courtiers and princes. And he was immediately successful:

I began to write the first issues with the greatest respect for my public – I believe that no writer has ever had such a respectful opinion of his readers as I had of mine. My intentions were first directed to Augsburg and Bavaria, than all the areas I had visited and finally the whole of Germany. [SLG II p. 8f.]

The applause was much greater than I could have expected under the circumstances. The circulation went from one hundred to hundreds, despite the fact that I myself was the least satisfied with my Chronicle. I wrote it – or, more accurately, dictated it in the tavern with a tankard of beer and a pipe of tobacco, with nothing to help me but my experience and that bit of sense that Mother Nature has given me. … I was on fire, knew how to interest people, knew how to write my mother tongue well, better than people were used to at the time. Not infrequently I also had satirical moments. [SLG II p. 9.]

Years of experience were suddenly at his fingertips: the polemicist, the religious debater, the teacher able to knock off a witty dictation for his class, the poet who had spent years supplying verses to order at short notice. All Schubart's literary talent and his experience therefore came together to make journalism the best of all occupations for him at that moment. After reaching his 'aphelion' in Munich, the farthest point from the sun, his journey back began here. He was on his way – to his doom, because, among all these skills he was lacking one quality: caution.

Journalism may have been the best of occupations for Schubart, but it was also the most dangerous, even in Augsburg.

Defending the faith

The first warning shot came about a month after Schubart had started to publish his German Chronicle. At that time Augsburg was ruled in religious parity, that is, a balance was maintained between Catholic and Protestant officials. Augsburg was a city that was experiencing a Catholic religious revival, aggressively countering Protestant theology. After years of mutual cohabitation, Catholicism was on the upward march in the city.

Schubart had started to attack the Catholics and particularly the Jesuits in the German Chronicle. An injudicious wish that Germany could have just 'a hatful' of the freedom enjoyed in England led, at the instigation of the Catholic Mayor of the time, to the imposition of a print ban on the German Chronicle in Augsburg. Undeterred and rash as ever, Schubart immediately started printing his journal in nearby Ulm and, also undeterred, continued his campaign against the Catholic hierarchy and particularly against the Jesuits.

Because of the vehemence of his views, at one point during this period Schubart had to appear in front of both of the Augsburg Mayors and explain himself. He seems to have got away with it, at least on that occasion, but the young hotheads of the Jesuit college did not forget.

Another of Schubart's Catholic targets was an Austrian Catholic priest, Johann Gassner, who claimed to be able to heal people just by the laying on of hands. He believed that many diseases were caused by demonic powers and could be cured by exorcism. Gassner had attracted a large following in southern Germany: for most of 1774 he was touring the diocese of Constance – which included most of Württemberg – and drawing huge crowds to his spectacles. Schubart wasted no opportunity to pillory Gassner in the German Chronicle and, without doubt, loudly and even more vigorously in the tavern.

The flight to Ulm, 1775

Schubart had to be accompanied by friends whenever he went out at night to prevent attacks by Jesuits and their supporters who waited for him on every corner. His son Ludwig, then nine years old, was staying with him at the time and going to school in Augsburg. Because of the threats, Ludwig had to share his father's bed for safety. His enemies threw stones through his windows. Father and son were driven to sleep under the bed for protection. Because at least some Catholics were well disposed to him, he tells us, he thought he would be safe. He was wrong.

One evening in January of 1775 he was sitting at home with some friends when his house was surrounded by soldiers. Some forced their way up the stairs and a deputy of the Catholic mayor came into the room and announced that Schubart was under arrest. His papers were seized, his property impounded and there was even an attempt to search the pockets of those present. His friends left and he was left alone. Some soldiers were in the room, some on the stairs and some around the house. An old man he kept as a retainer was escorted off to prison and interrogated for information about him. As news of his arrest spread his friends and the Protestant senators intervened for him and managed to obtain his freedom. He was now taken, surrounded by the rabble, to the Catholic mayor who told him he had to leave the city immediately. 'And my crime?' he asked the mayor. 'We do not act without cause and that should be enough for you.'

It may well be that the Mayor took the only decision he could in the circumstances. He needed to keep order in Augsburg and would clearly want to avoid disturbing the delicate religious balance in the town. It is certainly possible that he even saved Schubart's life by getting him out of the town as quickly as possible. After he left Augsburg copies of one of his poems were publicly burnt.

A large number of friends and pupils were waiting for him when he returned home and accompanied him with tears to the city gates and to the next village, where he could await the post-coach to Ulm. It was not going to be an easy journey. Schubart would only be out of danger when he reached Ulm.

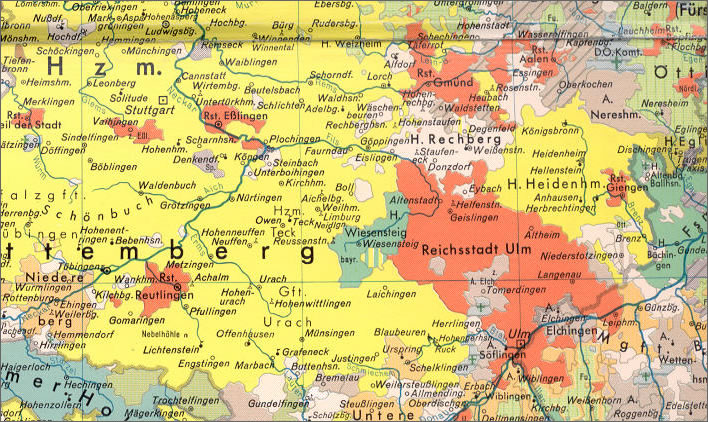

Have your passport ready. An image of the territorial complexity in southern Germany around 1789. Yellow is the Duchy of Württemberg, imperial towns are in orange. All the other colours represent structures that are too complex to go into here. Note the separate status of Günzberg (bottom right), where Schubart had his close encounter with enraged Catholic friars; Wiblingen, the small island of church territory on the southern edge of Ulm where Nickel was executed and Blaubeuren in Württemberg, just to the west of Ulm (both discussed in Chapter 4).

Only about 70 kilometres separate the imperial cities of Augsburg and Ulm, but those 70 kilometres crossed some of the most politically fragmented parts of Germany. On its way the post-coach passed through micro-territories, remnants of the Holy Roman Empire, some run by ecclesiastical bodies, some Habsburg, most of them Catholic. The overnight stop was in Günzburg and Schubart, knowing that his notoriety among Catholics had been spread widely, suspected there might be a problem even before getting there.

A narrow escape

As he entered the coaching inn in Günzburg he saw that there was a crowd of 'pot bellied Catholic clerics' sitting round a table drinking beer. One of the latest issues of the German Chronicle was in front of them:

You can imagine my fright, when I heard them shouting in their Hottentot dialect: 'Just give me that swine Schubart, I'd slice out his tongue and then burn the heretic alive. Then you can write, dog!' They were all shouting out of their brown-beer throats and banging on the table so hard that the glasses tinkled. [SLG II p. 63.]… The landlord was watching all this from a distance, his mouth wide open. What a welcome for me! My mouth went dry when I suddenly realised that this murderous gang would easily recognize me from the many portraits of me that had been circulated. [SLG II p. 64.]

Schubart quickly collected his wits, went over to join them and cursed this villain Schubart so extensively that the group were heaping praises on his head.

He slept badly, expecting to be attacked at any moment, his faithful poodle on his chest watching over him (Schubart was a lifelong dog lover). In the grey morning light he left Günzburg and shook himself 'like a rescued man on the riverbank.' For the rest of the journey he used an assumed name, finally arriving safely in Ulm.

References

-

^

All inline citations 'SLG' are to Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, Schubarts Leben und Gesinnungen, Erster Theil, Stuttgart, 1791.

The German text is available online at zeno.org -

^

The idea of the Zeitgeist that began to appear at this time is fitting for the confluence of ideas about the immense intellectual waste resulting from the lack of social mobility within a feudal system. Just at the time Daniel was growing up Thomas Gray was writing his poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1745-1750), which made the point eloquently in relation to the rural poor:

45 Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid / Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire; / Hands that the rod of empire might have swayed, / Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre.

49 But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page / Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er unroll; / Chill Penury repressed their noble rage, / And froze the genial current of the soul.

53 Full many a gem of purest ray serene, / The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear: / Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, / And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard -

^

The author of Schubart's substantial and generally fair entry in the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Band 32 (1891), S. 588–599, Adolf Wohlwill, is harsh in his opinion about the lack of control Schubart experienced that led to his wild and erratic character traits never being corrected by his parents. Academics with substantial careers and measured judgement who end up writing entries for the ADB have attained such positions through orderly and focused drudgery. Their opinions on the upbringing of young hotheads are flavoured by their own perfection.

ADB 'Schubart', original, Wikisource transcription. -

^

Kathrinchen hing an meinem Pferd

Eugen Nägele, Aus Schubarts Leben und Wirken, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1888, Anhang XV, 'Erinnerungen an die Geisslinger Zeit', p438. - ^ Nägele, ibid., p. 37

- ^ Nägele, ibid., p. 38

- ^ The title 'Spezial' refers to the rank of Deacon in the Pietist church of the time. Zilling was the most senior churchman in Ludwigsburg at the time. Schubart was the church organist and Zilling was therefore his immediate superior.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!