For the greater glory of God: Carl Schubert

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-05-01 07:46

The Oil Father

Setting out from Vienna, let us head almost due north into what is now the Czech Republic. After a few kilometres we pass into the region formerly known as Moravia (German: Mähren). About 160 km (100 miles) after Vienna we pass through Brno (Brünn), the former capital of the region. Another 160 km of travel northwards will eventually bring us, via Hanušovice (Hannsdorf), to the small village of Vysoké Žibřidovice (Hohenseibersdorf), almost on the border with Poland, the border area of which in Schubert's time was called Silesia (Schlesien). On a train the journey will take you a little under seven hours and require at least two changes.

From the western end of the village we take the tree-lined track along the edge of the field, turn left where two parallel tracks cross and follow the first one down for about 300 m through fields and small coppices. Our destination is now unmissably in front of us.

There, between two tracks that cross a rolling landscape of fields and woods is a large stone monument: an inscribed base the height of a person surmounted by a life-size, kneeling figure of a man, facing east, looking up to the heavens with hands clasped in agonised prayer. The figure is executed in a fine rococo style, the folds of the stone gown swept and convoluted, the lines of the noble face rendered in careful detail.

A photograph of the Ölvater from the 1930s.

A photograph of the Ölvater from 2013. The tree and the German hiking path signs have been removed. The landscape changes in 30 years are very marked. Image©: Jan Malach

The outer walls of the base and the sides of the pediment have decorated panels bearing religious inscriptions in German. The front of the central pediment on which the figure kneels also bears a German inscription:

ER GING NACH SEINER GEWOHNHEIT AN DEN ÖLBERG, LUC. Cap. 22, v. 39

And he (came out, and) went, as he was wont, to the Mount of Olives. Luke 22, v 39 (King James Bible).

We are now standing on the lower slopes of a hill called by the locals at one time the Ölberg, the 'Oil Mount', on a gentle ridge that runs between the two villages of Neudorf (now Vysoká) and Hohenseibersdorf. The sandstone figure illustrates a key moment in the crucifixion story:

39 And he came out, and went, as he was wont, to the mount of Olives; and his disciples also followed him. 40 And when he was at the place, he said unto them, Pray that ye enter not into temptation. 41 And he was withdrawn from them about a stone’s cast, and kneeled down, and prayed, 42 saying, Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done. 43 And there appeared an angel unto him from heaven, strengthening him. 44 And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground. 45 And when he rose up from prayer, and was come to his disciples, he found them sleeping for sorrow, 46 and said unto them, Why sleep ye? rise and pray, lest ye enter into temptation.[1]

This astonishing rococo construction standing solitary in a field on a ridge between two a small hamlets on the edge of the Czech Republic has survived here for nearly two and a half turbulent and violent centuries. On the rear face of the main plinth we read:

AUFGERICHTET VON EINEM UNWÜRDIGEN LIEBHABER CARL SCHUBERT AUS NEYDORFF IN NO. 41 ANNO 1780

Erected by an unworthy lover Carl Schubert of Neudorf, no. 41, in the year 1780

This Carl Schubert (1723-1787) was Franz Schubert's grandfather.

Carl Schubert, pious farmer

He lived in Neudorf, the village over the other side of the ridge from where we are standing, across the narrow valley, now filled with trees, that runs alongside our track.

Carl is variously styled as a farmer or flax dealer and must indeed have gone often, 'as he was wont', along this way. Given that a major local product was flax – and therefore linseed oil – it seems reasonable to assume that the local name 'Oil Mount' is probably more that just a simple biblical allusion. Carl's German Bible, unlike an English Bible, would not say anything about olives: for him the place where Jesus was 'wont' to go was just the Ölberg. His statue became known among the local inhabitants as the Ölvater, the 'Oil Father'.

For the main inscription on his monument Carl chose Luke's account of Christ's agony, which is the only one to mention the Mount of Olives as such. Matthew and Mark locate the scene in the garden of Gethsemane (a word meaning 'oil press'), John has the group entering 'a garden'. This means that, of the four accounts of the agony, only that of Luke fits the name of the hill above Neudorf and this is the gospel to which Carl specifically refers.

Not only that, but it is Luke's version that most graphically describes the agony of Christ and most fittingly represents the kneeling figure. However, in one of the other inscriptions on the base Carl also quotes from Matthew's version of the agony, 26:38:

My soul is deeply grieved, to the point of death; remain here and keep watch with Me.

It seems clear, if only from this, that Carl chose Luke as his principal source quite deliberately. We do not know, of course, whether there may have been some deeper significance for Carl in the account of the agony in the garden, in which Jesus foresees his imminent and terrible death but despite his agony – his sweating 'as it were great drops of blood' – accepts the will of his Father.[2]

The price of piety

I know of no record of how much money Carl spent creating this monument, but it must have been a substantial amount. There is, however, no wild rococo extravagance, no swirling clouds and floating angels, no sleeping disciples in dramatic perspective. Less is indeed more: the solitary figure alone in a field with his God.

Carl and his craftsmen stepped outside the tradition of simple wooden or stone structures with a crucifix or other devotional object erected by the wayside of well frequented routes. Carl's Ölvater is not just a routine exercise in piety, it is a cultural and intellectual gesture of a high order, here, solitary, beside a track in a field. It tells us in unmistakable language that its progenitor – the tenant, the smallholder, the farmer, the flax merchant in a hamlet on the eastern edges of the Habsburg empire – was a cultured and thoughtful person. He put up an impressive monument with his own money almost, as we now say, in the middle of nowhere. It was set upon foundations that have lasted for two and a half centuries and was carved out of sandstone by skilled rococo sculptors. We must conclude that Carl Schubert was not only exceptionally pious but also that he must have been rich enough and cultured enough to be able to erect a structure of this quality.

In May 1781, after it was finished, the notables of Neudorf – among them two of Carl's nephews and the local magistrate – set down on paper a solemn promise to maintain and repair Carl's monument at their own cost. The document was not just signed but also bore the seals of the participants 'as a sign of their guarantee, into which they had freely and consciously entered'. In giving this guarantee they clearly had no idea of the upheaval, misery, blood-letting and devastation that would sweep over this area in subsequent centuries.

By some miracle, as Carl would undoubtably see it, his Ölvater is kneeling still, its face in that dark night of the soul gazing up at the sky towards the first light over the low hills to the east, a dawn just as Carl would have seen many times all those long years ago on the way 'he was wont to come' from his house,

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.[3]

Seven years after his Ölvater was finished, Carl died of a perforated bowel. His son Franz Theodor Schubert, the composer's father, recorded his passing in the family chronicle:

On 16 [correct: 24] December 1787 at three-thirty in the morning my dearly loved and respected father Karl Schubert died.[4]

The Schubert family home in Neudorf in 1930.

The Schubert family home in Neudorf in 2013, after the postwar expulsions of the German-speaking inhabitants of 'Sudetenland' by communist Czechoslovakia and the subsequent razing of their property. Throughout Moravia and Silesia the story was the same: many properties of the former inhabitants and even whole villages stood empty, fell into ruins and were razed without trace. Image ©: Jan Malach

Pious egotism

Carl Schubert, an intensely pious Catholic farmer in Moravia, spent his money on a religious monument and a chapel and thought thereby on the greater glory of God and the survival of his soul. Apart from putting some money into the pockets of the local rococo sculptors and stonemasons his gestures had no further effect – they were simply egoistic.

This is not a personal criticism of him – he was just acting within the Catholic culture of his times. On a personal level, by his effort and his husbandry he gave his two sons the base from which they both made the leap out of agricultural oblivion to the life of the metropolis at the centre of empire. We have to thank Carl and his wife for giving us the father (and uncle) that in turn gave us Franz Schubert, the Viennese musical genius.

Apart from that, though, two and a half centuries later we have been left an interesting and surprising monument with a slight touristic utility.

An orphanage, a factory, a stock or share, on the other hand, is not egoistic: it is an investment that produces practical benefit here on earth, an example of Protestant good works for the glory of God.

Carl could have spent his money on improving the processing of flax, one of the major products of the region where he lived. He could have built new stalls for his animals and improved the transport infrastructure in the area, thus facilitating export. He could have built grain storage, that would have helped his village to survive the recurring times of famine. He did none of this. He saved his soul with a pious statue.

When, despite everything, a Catholic life was economically successful, the donation of its proceeds for some religious purpose – for example Carl's Ölvater – was more effective in gaining salvation than the process of earning the money in the first place.

But even sceptical and irreligious people used donations to cover themselves, just in case. It was anyway better to have the insurance to cover the uncertainties of the state of grace after death and because also (at least according to the widely held, convenient opinion) the external subjugation to the commandments of the Church was sufficient for salvation and could be achieved for all specific circumstances by the payment of generic indulgences.[5]

Dealing with surplus money

Carl's monument mentality was everywhere in the Austrian Empire. The witty Berlin writer Adolf Glassbrenner (1810-1876), en route to Vienna, stopped off in Prague, the capital of Bohemia, an important and long-standing part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Although he had pleaded with his guide to stop taking him to religious sites – 'there must be as many holy images to see in Bohemia as warning signs in Prussia' – in Prague he ended up wandering around the immense Cathedral of St Vitus. He noted priests standing at various altars, kneeling and kissing and 'doing their business' [the satirical joke is the same in German as it is in English]. He finally came to the ornate solid silver tomb of Saint John of Nepomuk and viewed it through the gimlet eye of a Prussian Protestant:

I stood in holy meditation in front of the silver tomb of the sainted Nepomuk. It weighs 36 hundredweight (~1.7 tonnes) and used to weigh even more. If only you had this 36 hundredweight of silver, I thought, and wiped a great tear from my eye, how many unhappy people could you make happy, how many disconsolate people could you console! You would go in the street and throw handfuls of it among the people, shouting: 'Look what Saint Nepomuk has done for you! He climbed out of his grave, saw with indignation its useless adornment then gave it to me with the words: "Go and give it to the poor, so that they no longer cry for bread. Tell them that the truly pious person needs neither church nor splendour to lead his thoughts to God."'[6]

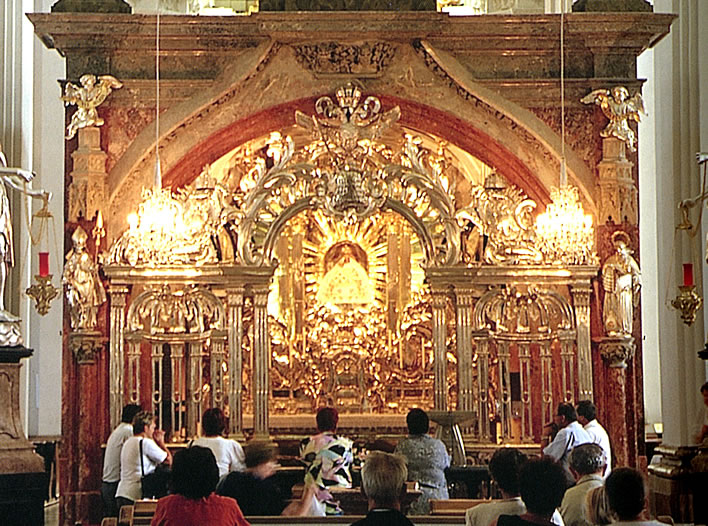

The grave of Saint John of Nepomuk in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Saints Vitus, Wenceslaus and Adalbert in Prague. The statue was created in 1736, extended in 1748 and consists of 1.68 tonnes of silver.

Speaking of silver, this is the Gnadenalter, the 'Altar of Mercy' in the Austrian pilgrimage Basilica of Mariazell, a favourite pilgrimage destination for the Habsburg emperors, particularly Maria Theresia, who held her survival and the successes of her reign to be due to the timely intercession of the Virgin Mother. It was she who donated the impressive silver screen in front of the altar. The statue of the Virgin within became famous for its miraculous powers, and is still honoured today as the Magna Mater Austriae, the 'Great Mother of Austria'.

References

- ^ The Bible, (King James Authorised Version), Luke 22:39-46.

-

^

The choice of quotations that Carl Schubert placed on his Ölvater, not all of which come directly from Biblical texts, imply a particular association with the concept of the Holy Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Ghost. During the times of the Turkish invasions the Trinity became a distinguishing symbol of Christianity in opposition to the non-trinitarian Islam. The reverence for the Trinity was also a distinguishing factor against the Deists and the other non-trinitarian sects who were prevalent in Silesia and Moravia at that time. The associated doctrine of redemption through the intervention of Jesus, one component of the Trinity, was particulary strong at times of plague, which had caused serious loss of life in Carl's village and which were held to be divine punishments for sin. Prayers were directed to the Trinity, simultaneously judge and redeemer. [see: Anna Coreth, Pietas Austriaca, Ursprung und Entwicklung barocker Frömmigkeit in Österreich, Verlag R. Oldenbourg, München, 1959, p. 15f.] Note also our note on the Viennese Plague Column, also dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

If there were any doubt we merely need to note that only two years after Carl had erected his Ölvater on the ridge in 1780 he was involved in even more pious spending. He joined with two of his nephews – Joseph Johann (1741-?), son of his brother Joseph (1707-1756) and Johann Joseph (1747-1804), son of his brother Johann (1712-1763) – to build a chapel in Neudorf: the Chapel of the Holy Trinity. - ^ Thomas Gray, 'Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard', Thomas Gray Archive, 23 Sep 2013, ll. 99-100.

- ^ Otto Erich Deutsch, ed. Schubert: die Dokumente seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996, p. 4.

-

^

Weber p. 59.

Aber auch skeptische und unkirchliche Naturen pflegten, weil es zur Versicherung gegen die Ungewißheiten des Zustandes nach dem Tode immerhin besser so war und weil ja (wenigstens nach der sehr verbreiteten laxeren Auffassung) die äußere Unterwerfung unter die Gebote der Kirche zur Seligkeit genügte, sich durch Pauschsummen mit ihr für alle Fälle abzufinden. -

^

Adolf Glassbrenner, Bilder und Träume aus Wien, Wien : Rikola-Verlag, 1922, p. 22.

Ich aber stand in heiliger Andacht vor dem silbernen Grabmale des heiligen Nepomuk, das sechsunddreißig Zentner wiegt und früher noch mehr gewogen hatte. Wenn du diese sechsunddreißig Zentner Silber hättest, dachte ich und wischte mir eine große Träne aus den Augen, wie viele Unglückliche wolltest du glücklich machen, wie viele Trostlose trösten! Du würdest auf die Straße gehen, mit vollen Händen Geld unter die Leute werfen und ausrufen: »Seht, das hat der heilige Nepomuk für Euch getan! Er ist heraufgestiegen aus seinem Grabe, hat mit Unwillen den nutzlosen Schmuck betrachtet, und ihn mir gegeben mit den Worten: »Gehe hin und gib den Armen, auf daß sie ferner nicht mehr um Brot schreien. Sage ihnen, daß der echt fromme Mensch weder der Kirche, noch des Glanzes bedürfe, um sein Gemüt zu Gott zu richten; [sage ihnen, daß die schöne Natur mit ihren Wunderschöpfungen ein unentweihter Tempel des Herrn, und daß Bewunderung und Genuß alles Schönen das heiligste Gebet sei!«]

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!