Renewal, 1782

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-05-15 18:48

A turning point

Rieger continued to persecute Schubart in Hohenasperg for another six months after Schiller's visit. The persecution finally stopped when Rieger died suddenly on 15 May 1782, sixty years old, of a stroke brought on by a fit of rage at a soldier's disrespectful answer. It is said that the soldier responded to a request or command of Rieger's with the Berlichinger Gruß, sometimes known as the 'Swabian salute': Leck mich am Arsch, 'Lick my arse!', famously employed by Goethe in his play Götz von Berlichingen (1773).

With Rieger's death we reach another milestone in Schubart's incarceration in Hohenasperg.

Rieger and Zilling, although they nearly killed him in the process, did not succeed in breaking Schubart's will, essentially because there was no will there to be broken in the first place. Throughout his life Schubart could go from moments of the deepest piety to moments of wild, worldly lust and back in the blink of an eye. An officer stationed in Hohenasperg described the Schubart of 1782, five years after his incarceration had begun:

[…] as much as one must admire his great, but unfortunately completely misdirected talents, so contemptible are his crawling flatteries. He has often made my belly ache with laughing, but I often leave my room to avoid bankrupting myself. The man drinks like the sieve of the Danaids, and in the middle of the most serious discussion of religion and eternity he expresses the wish that humanity could just have one arsehole in order, out of love, for him to be able to lick its arse. This contrast, this jumping from one thought to another, this transition from a sentiment to its complete opposite make the 42 year old man sound like a silly boy, causing him, in the eyes of some, to lose all credibility. […]

I have never before seen such an original fellow, however he often asserts the most absurd things. He recently came to me and contradicted the Copernican system using proofs from the Bible. I said: 'Herr Professor, I can see that you are getting old'. This forcefully expressed truth brought him back and he embraced me.

Briefe 2:23f. [20 March 1782]

The officer's observations may help us to understand a puzzle that confronts us on Rieger's death. For five years Rieger had psychologically tortured the helpless Schubart with a completely hypocritical, Pietist sadism. Schubart characterised him as a 'beast'. Yet after Reiger's death, when he was no longer any threat to him, Schubart wrote encomiums on him for his family, for his troops and even wrote a lengthy appreciation of him to be chiselled into his memorial in the Michaelskirche in Asperg.

The modern mind might reach for stretched explanations such as Stockholm Syndrome, for example – that Schubart, the victim, had bonded with Rieger, his oppressor.

But this cannot be valid, since Schubart is simultaneously cursing Rieger and writing flatulent poems in praise of him. We might think that the poems were intended just as passing flattery, but let's not forget that Rieger was by then a corpse and immune to such things, and also that Schubart not only wrote these hymns, he published them in his collected poems.

We can only agree with the officer's observation that Schubart could hold two completely contradictory thoughts in his brain simultaneously. Carried away on wings of rhetoric his mind could follow one path or the other. For his own safety during his incarceration he surpressed one of the paths – or at least kept it to himself.

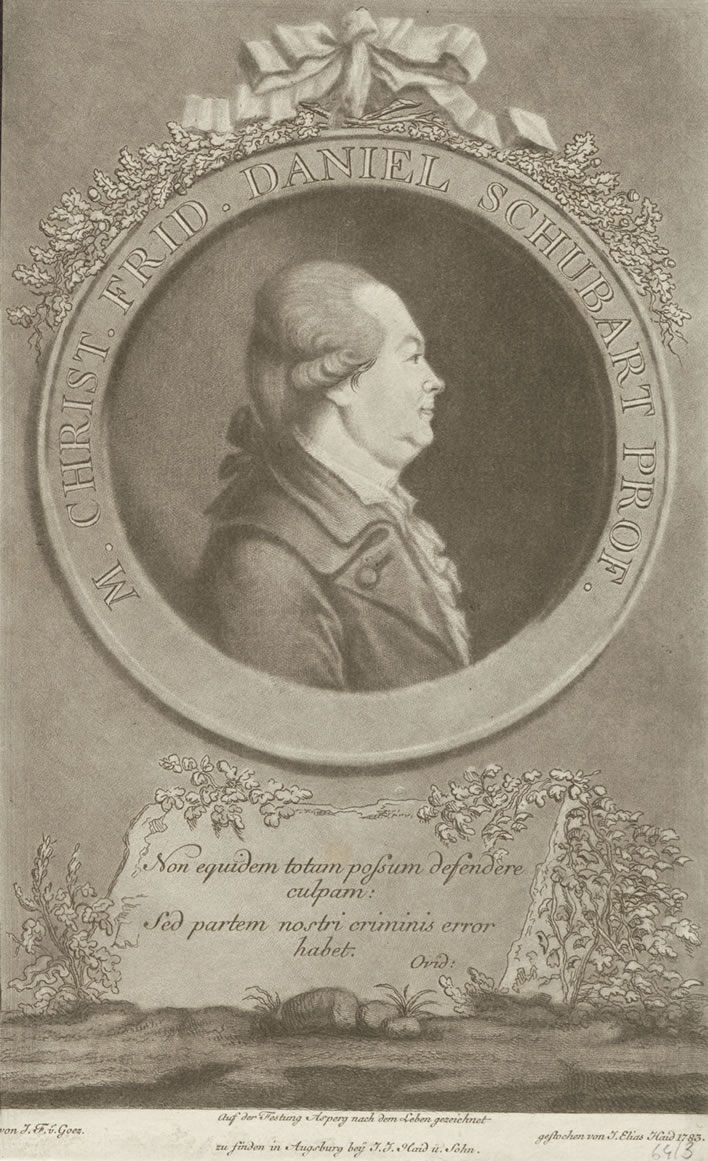

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, mezzotint by Johann Elias Haid (Augsburg) after an image by Joseph Franz von Goez (1754-1815), 1783. Auf der Festung Asperg nach dem Leben gezeichnet, 'Drawn from life on the Fortress Asperg'. The inscription on the tablet at the base is Non equidem totam possum defendere culpam: / Sed partem nostri criminis error habet. / Ovid:, 'I cannot indeed exculpate my fault entirely, but part of it consists in error'. P. Ovidius Naso. Tristia, Book III, poem 5, ll. 51-2. Image: ©Tobias-Bild Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen.

A letter of Schubart's to Helene after Rieger's death exposes the conflicts in his mind. Today we might talk of an emotional rollercoaster:

I had to endure many deep sufferings at the hands of the previous Commander. It was not seldom that he treated humans like animals. But God directed his heart from time to time to do good things for me. And when I think of that, all my dislikes disappear and become benedictions. From the enemy now cast down my anger flies up to heaven like an eagle.

Briefe 2:31.

His new Commander was General von Scheeler, a much more likeable and humane person than Rieger. Schubart told Helene that the new Commander was

an angel, gentle and good. I thank God, who gave him to me as a rehabilitation. I shall teach his children with pleasure, because he, unlike his predecessor, will never hinder my freedom for his own purposes. […]

My comfort, next to God, is the good-hearted commander and his wife who treat me in a Christian way.

Briefe 2:31f, 2:33.

As Schubart regained his freedoms bit by bit – writing, corresponding, playing the piano – so his rage at the injustice of his imprisonment grew ever stronger. In the summer of 1782 in a secret letter to Helene his anger and misery overflowed:

It is impossible for me to give you a true idea of all my suffering. Years go by and I groan in vain after freedom. Murderers, sodomites, highwaymen that were imprisoned with me have gained their release – and I! your husband! am miserably without hope. […] O, death would be the best thing for me. […] I have days when I can't bring myself to do anything […] I hope that this life will end soon. I am weary in all my joints, sleep little, rarely eat with appetite and don't have a moment of pleasure. […] O pray for my death! I have suffered enough under the tyrant's whip.

His immediate tormentor now dead, Schubart's hatred was now directed at the source of his troubles, Carl Eugen, a 'Satan', as he called him. [Briefe 2:119] In that year he wrote two poems that were to become the only literary pieces for which he is remembered. They are the testament that he was back from the pit.

One of these was Die Forelle, 'The Trout' [Gedichte 139f.], which we have already considered in depth. The poem can be read as an extended metaphor for Schubart's entrapment and arrest. Schubart set it to music himself [Holzer 175], a setting which bears no comparison with that of his near namesake Franz Schubert and which has been deservedly forgotten.

The other poem is Die Fürstengruft, 'The Crypt of Princes'.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!