1775. Lili: the first Gotthard journey

Posted by Richard on UTC 2017-09-20 10:17 Updated on UTC 2017-11-19

A trip to Switzerland was initially planned in the spring of 1775 by some of Goethe's friends, all in their mid-twenties at the time: the two Stolberg brothers, Count Christian (1748-1821) (27) and our old friend, Count Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg (1750-1819) (25), together with their friend Freiherr Christian von Haugwitz (1752-1832) (23).

A woman went with Goethe, but only in spirit: He had adopted the Stolbergs' little sister, Augusta Louise (1753-1835) (22) – 'Gustgen' – as his special penfriend, even referring to her as his sister. They never met, but exchanged an enormous number of gushing letters and notes – just one more of the many psychiatric oddities in the Goethe case-notes.

Goethe was 26 years old at the time and dabbling in his profession of lawyer in Frankfurt and Wetzlar. He hated the job: his clients usually had someone else to thank that their work was somehow completed satisfactorily.

During his time at Wetzlar he had sunk deeper and deeper into a passionate love affair with Charlotte Buff – 'Lotte' – the fiancée of his colleague in his law practice in Wetzlar. Seducing other men's women, if only emotionally, was a Goethe speciality. His infatuation with Lotte gave him the background plot to the novel that made his name overnight: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers. At the conclusion of the novel poor, lovelorn Werther shot himself with messy incompetence; Goethe's solution to his emotional entanglement was not suicide, but that other speciality of his: flight.

Charlotte Buff (1753-1828), Goethe's squeeze in Wetzlar in 1772. She had been engaged since 1768 to Johann Christian Kestner, Goethe's colleague, superior and supposed friend. She and Kestner married, despite Goethe's interventions, in 1773.

Goethe took the emotions of the real-life situation and created out of them his enormously successful scandal-novel Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, 'The Sorrows of Young Werther', in which Charlotte is Lotte, Kestner is Albert and Goethe is the lovelorn Werther. The image is based on a painting of Charlotte by Johann Heinrich Schröder (1757-1812), a pupil of Tischbein's.

Lili

Goethe fled Wetzlar and returned to Frankurt, forgot Lotte in short order and within a few weeks was head-over-heels in love with the 17-year-old Lili Schönemann (1758-1817), a Frankfurt banker's daughter. They became sort-of engaged, a relationship which would turn out to be as turbulent and ultimately uncommitted as his sort-of engagement had been to his first great love, Friederike Brion (1752-1813), the vicar's daughter in Sesenheim five years before.

Anna Elisabeth (Lili) Schönemann (1758-1817) in 1782. She was Goethe's girl-to-die-for in Frankfurt in 1775. She was the daughter of a Frankfurt banker. In associating with her, the commoner Goethe was batting hopelessly above his league. After much Sturm und Drang the relationship ended – as end it must.

The image is a pastel drawing from 1782 by Franz Bernhard Frey (1716-1806), a painter and pastellist who was active in Paris and Alsace. This is a stunning piece of work, arguably much better than any of Frey's other pastels of female sitters. Lili clearly inspired him. Her expression is exactly that of the cool, distant dominance that we find in the descriptions of her manner with Goethe.

Goethe and Lili's sort-of engagement lasted for about six months and could not survive the opposition of their respective families. Her family was noble and rich; his family, though well-thought of and relatively well-off, in the feudal scheme of things were still only bourgeois swamp-dwellers. Neither family was happy at the thought of social commerce with the other, let alone sitting in the same room. Even Cornelia, Goethe's beloved sister, 'commanded' him to break it off. [Dichtung (4:18)781]

Goethe had the chance to go to Switzerland with the Stolbergs, but dithered as he tumbled in the maelstrom around Lili for some time. After a few weeks of the turmoil and intrigues that he and Lili's sort-of engagement had triggered, Goethe fled, without even saying a proper goodbye to his sort-of fiancée, just dropping her a hint. His departure from the previous love of his life, Friederike Brion, had been equally precipitious and duplicitous – she didn't even get a hint. His flight from Lili, he tells us much later, was an attempt to answer that egotist's question: could he live without her? [Dichtung (4:18)775]

On the road with the Werthers

Our escapee cast his lot in with the Stolbergs and Haugwitz and they set off for Switzerland, leaving Frankfurt on 14 May.

The group had all had 'Werther Uniforms' made for them, a mode of dress that Goethe had made infamous in his scandal novel that had given him immediate notoriety the year before, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers: A blue coat with a yellow waistcoat, yellow trousers, brown Stulpenstiefel (boots with turned over tops – think of 'Puss in Boots') and round hats of grey felt.

As we have already noted, in the book, Werther kills himself inefficiently for love and expires messily and lingeringly. We heartless, image-aware moderns may suspect that Werther's style choices may have played some role in his demise. Goethe, in making so much of the outfit, may have even agreed: in his suicide note Werther expresses the wish to be buried in his clothes and in the death scene the mortally wounded man is described as lying there booted, in a blue coat and yellow waistcoat. [Werther 2:152f]

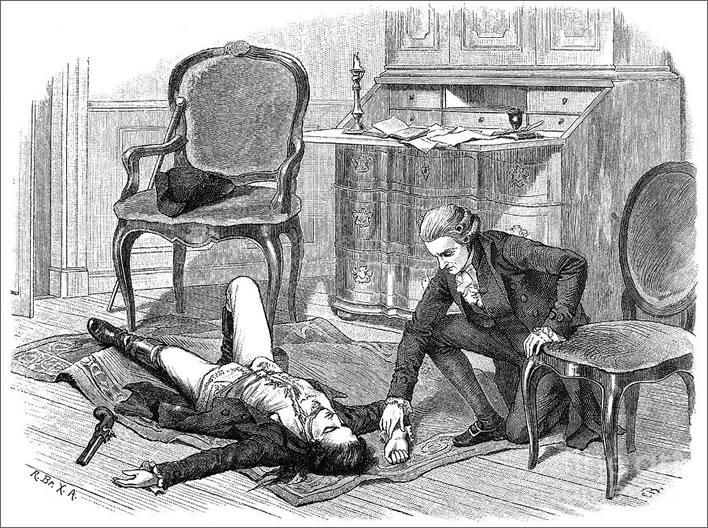

Werther, having ruined a perfectly good rug, on his long way out. The scene depicted here is a pretty good match for the death scene in the book:

When the doctor arrived for the unfortunate man he found him helpless on the ground, a pulse could be felt, the limbs were all paralysed. He had shot himself above the right eye through the head, some of his brain had been blown out. For good measure the doctor bled him from a vein in his right arm: the blood flowed, he still breathed.

From the blood on the arm of the back of the chair it could be concluded that he had done the deed while sitting at the writing desk, after which he fell down and thrashed convulsively around the chair. He now lay collapsed on his back towards the window. He was fully dressed, booted, in a blue coat with a yellow waistcoat.

He shot himself at midnight and died the following noon.

Goethe didn't invent the style, he took it from the human model for the Werther character, an acquaintance of his, Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem (1747-1772), whose striking outfit he described in Dichtung und Wahrheit[Dichtung (3:12)584]. In the craze that followed the publication of Werther, lovelorn and would-be lovelorn young men throughout Germany took to wearing such outfits, some of them even committing suicide. Some towns in Germany actually banned the wearing of the 'Werther Uniform'.

Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem (1747-1772), a pastel copy of a protrait painted around 1770. Goethe first met him when he was studying Law at Leipzig between 1765 and 1768. They met again in 1771 in Wetzlar. Like Goethe would with Lili, Jerusalem, too, fell for a high-ranking female, in his case already married to a high-ranking male. The impossibility of attaining his love and the scandal surrounding the liason led him to commit suicide on 29 October 1772 in his apartment – as inefficiently and as messily as Werther would do. We note the bright blue coat but cannot see the yellow waistcoat.

The image is taken from the pastel hanging in the Jerusalemhaus in Wetzlar, with some difficulty, since the museum goes to great lengths to avoid allowing you to see this portrait unless you pay 3 EUR to go in and see it.

Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1757-1828) in a portrait painted around 1796 by Georg Melchior Kraus (1737-1806) based on a preliminary picture by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein (1750-1812).

The Duke's blue coat, yellow waistcoat and trousers and brown boots correspond to Werther's famous uniform. In recognition of this fact, some of the reproductions of this picture have their colour tones altered to make the coat bluer and the trousers yellower. We have based our colour tones on the hunting-dog: if the dog looks right, so does its owner. The extremely prominent star of the Prussian 'High Order of the Black Eagle' worn on the uniform of the lovestruck suicide Werther adds some unintended comedy to the scene.

Good 18th century portraits told stories. Here the Duke is telling us he likes hunting, loves his dog and likes dressing up like Werther. No favourite books, artworks or imposing castle, let alone his much traduced wife. He was quite a short man, so stretching him out in this pose is one of the bread-and-butter skills of court painters.

The portrait is in the Goethe-Nationalmuseum Weimar, who will do their best to stop you seeing it, unless, of course you turn up and pay them something.

We only know of this fascinating and amusing detail of the adventure from a letter written by Christian Stolberg on 14 May, 1775. It is not mentioned in the fourth part of Dichtung und Wahrheit, that deals with the journey of 1775. Perhaps the old Goethe, then almost dead, thought better of perpetuating this image.

Thanks to Christian Stolberg, however, we moderns have to cope with the vision of a Werther tribute band, the 'Werthers' (the replicas not the originals), on a long journey through southern Germany with many stops that brought them to Strasbourg on 23 May 1775. Earlier on the journey Friedrich Stolberg had confessed to Goethe that he, too, was in recovery from a love addiction, in his case his passion for an English girl, Sophie Hanbury. [Dichtung (4:18)776f] The letter terminating the relationship was waiting for him on his arrival in Strasbourg, a moment that Goethe himself witnessed. [Morris 25 July 1775, p. 283] It appears that the tribute band now had at least two moping members, but so far no one had killed himself.

In the party for this part of the journey was the poet and Goethe admirer Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz (1751-1792). Goethe and Lenz split from the group to go to Emmendingen (just north of Freiburg im Breisgau), and visit Goethe's sister Cornelia (1750-1777) and her husband Johann Georg Schlosser. Cornelia had a tragic life and died only 26 years old, but that's another story. Lenz's life was also a disaster, but that, too, is another story. Back to the 'Werthers'.

Zurich and Lavater

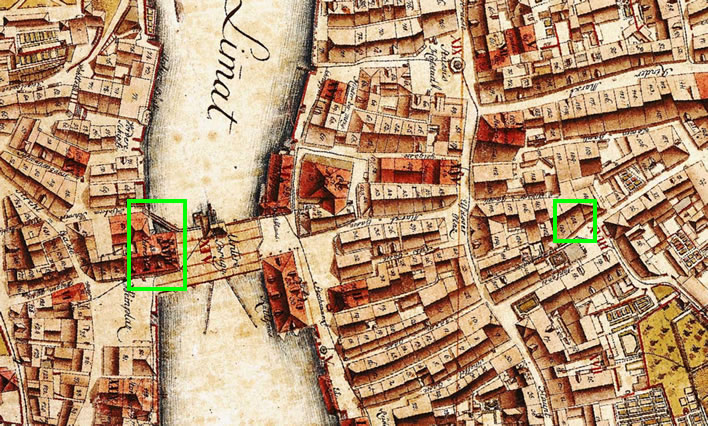

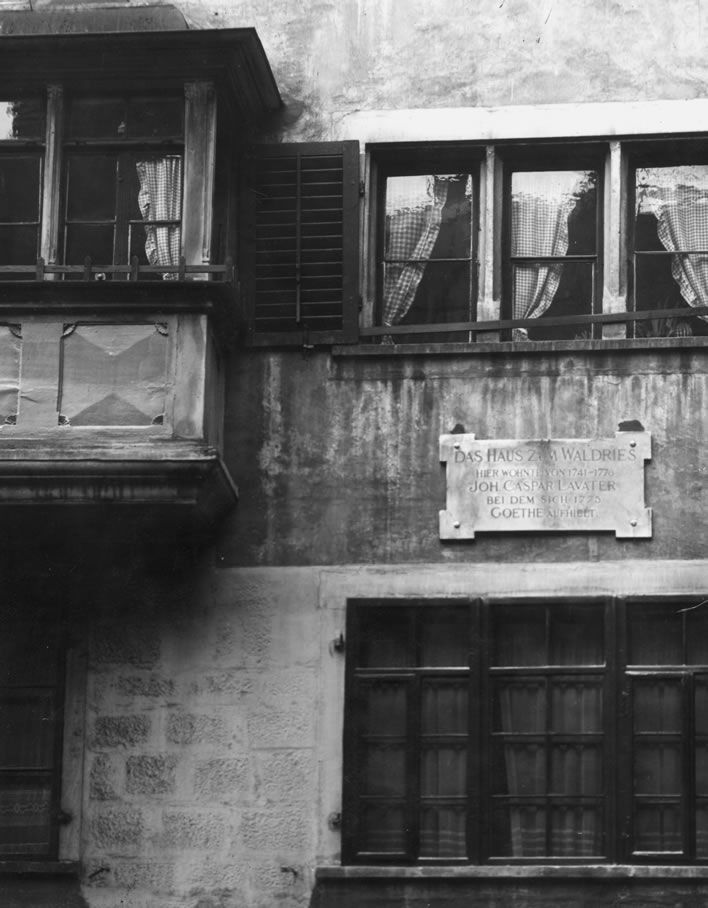

The Stolbergs and Haugwitz were in Strasbourg until 28 May. Goethe left Emmendingen on 6 June, finally arriving in Switzerland at the Rheinfall in Neuhausen/Schaffhausen on 7 June. The group, reunited somewhere along the way, possibly only in Zurich, then turned up in Zurich on the 8th, at the Haus zum Schwert, a renowned hotel on the left bank of the Limmat, by the Weinplatz/Rathhausbrücke. Goethe stayed one night, then moved in with Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) in the Spiegelgasse 11 (Das Haus zum Waldris), not far away. The Stolbergs and Haugwitz stayed in the Schwert for a few more days then on 13 June moved to a cottage in the Enge quarter of Zürich, close to the lake and then quite rural, which they had rented from a farmer, Jakob Beerli. Goethe introduced them to Lavater on 10 June.

The centre of Zurich in the 'Müllerplan' of 1793. The green rectangle on the left marks the Haus zum Schwert at one end of the Rathausbrücke on the left bank of the Limmat – a prime location. The small green rectangle on the right is Caspar Lavater's house, Spiegelgasse 11, where Goethe stayed, only a few minutes' walk away from the hotel.

Update: 19.11.2017: An image of the Rathausbrücke looking across to the left bank of the Limmat and the Weinplatz, c. 1500. The Haus zum Schwert is the building abutting onto the bridge. The image is a reproduction of a painting showing the Üetliberg by Hans Leu der Ältere (1460?-1507). The painting was originally on one of the altarpieces in the Grossmünster and is now in the Landesmuseum Zürich. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Lavater, now largely forgotten outside Switzerland and outside Goethe studies, had a theory that human character could be deduced from the characteristics of the head, particularly from examination of the silhouette profiles that were so popular at the time. His efforts were well-regarded by some, in a age obsessed with the Denkerstirn, the high forehead associated with intellectual prowess (think of the Roswell alien). One woman noted the flush of desire that came over her whenever she gazed at Kant's Roswellian forehead in one of his portraits.

Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) in a beautifully rendered 1785 portrait by the Swiss artist Alexander Speisegger (1750-1798). Lavater sent this to his friend, the writer Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim (1719-1803) in Halberstadt. This portrait is – Gleimhaus Halberstadt be praised! – freely available online.

Goethe and Lavater had corresponded for some time before their first meeting in 1774, the year before Goethe's first Swiss journey. Goethe, himself not a Christian, also venerated Lavater at first for his sermons and religious insights, even referring to him gratuitously and approvingly twice by name in Werther, of all places. [Werther 1:38; 1:99] In Goethe's head, sooner or later, everything was connected.

Lavater, himself the owner of a fine nose, is easy to mock for his physiognomic theories: Lavater's 'analysis' of any particular profile was completely subjective and completely unscientific, the terminology used was full of feeling and rhetorical excess, quite poetic in fact. It would not be out of place in a modern Mills and Boon romance.

His religious interpretations were also rather odd, placing great faith in miracles, but in that large contemporary field of religious oddities they were not strikingly bonkers. In an increasingly schismatic, faithless and rationalistic age, a belief in miracles might be a comforting thing. His faith in miracles even convinced him that sooner or later Goethe would come round to Christianity.

But in fairness we must record that Lavater had a freedom fighter personality and had on several occasions in his youth risked opprobrium, his livelihood, his freedom and his life by standing up against injustice. Some of his ideas may have been laughable in our modern terms, but he was a very brave and principled man. He died by the bullet of a French soldier fired at him (probably accidentally) in the Second Battle of Zurich on 26 September 1799. The bullet could not be removed and he died a lingering death, finally expiring on 2 January 1801.

Sticking it to the Stolbergs, part I

Goethe the genius, now staying alone with Lavater the genius, separated from his aristocratic travelling companions, grew tired of them, we might even say that he grew embarrassed at their aristocratic antics – at least, so Goethe tells us in Dichtung und Wahrheit, 'Invention/Poetry and Truth', in a section written around fifty years after the fact in which he viciously attacks them: they had even had the 'youthful aristocratic arrogance' to call on Lavater without an appointment. [Dichtung (4:18)785]

Update: 19.11.2017: The Haus zum Waldries, Spiegelgasse 11 in Zurich, where Caspar Lavater lived and where Goethe stayed on two of his three visits to Zurich. Image: Photographer Wilhelm Gallas. No date. Zürich Baugeschichtliches Archiv. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Update: 19.11.2017: The plaque on the Haus zum Waldries, Spiegelgasse 11, Zurich, memorialising Lavater and Goethe. 1930. Image: Photographer Wilhelm Gallas. No date. Zürich Baugeschichtliches Archiv. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Oiled with a large measure of self-satisfaction, Goethe then goes out of his way to tell us of Lavater's explicit condemnation of Leopold Stolberg's character as 'soft and malleable' and Lavater's implicit surprise at why Goethe was associating himself with such noble riff-raff. The memory of Lavater's condemnation of Leopold Stolberg's character was so pleasing to the old Goethe that he included it in Dichtung und Wahrheit twice. [Dichtung (4:18)785; (4:19)806]

In Dichtung und Wahrheit Goethe set the stage for his attack on the Stolbergs before he even set off, using his old friend Johann Heinrich Merck (1741-1791) – whom he would also simultaneously attack – as his proxy. The relevant passage offers an insight into this repellent side of Goethe (and includes even more skinny-dipping):

I spent some time with Merck, who looked with a devilish sideways glance upon my planned journey and on my companions, who had also visited him, describing them with pitiless understanding. He also knew me well: the insurmountably naive amiability of my character was painful to him; my eternal acceptance of others, my live-and-let-live attitude was a torture. 'That you are travelling with these characters', he shouted, 'is a stupid joke'

[…]

'You won't stay long with them!' was the conclusion of his tirade.

[…]

Unfortunately, before the group left Darmstadt, there was an incident that irrefutably strengthened Merck's opinion.

One of the crazes of the time was that one should try to set oneself in a natural state, which included bathing in open water in the open air. Our friends [Stolbergs and Haugwitz] just could not resist, after all other proprieties, this unseemly activity.

Darmstadt, although on a sandy plain without flowing water, has a pond nearby, which I had never even known about before this moment. The strongly natural and continually over-heated friends sought refreshment in this pond: the sight of naked youths in broad daylight was certainly unusual in this area. There was a scandal in any case. Merck hardened his opinions and, I can not deny it, brought forward our departure.

Dichtung (4:18) 775f.

Goethe's distaste for his noble companions is a phenomenon of his later years. It did not prevent him continuing on the next part of his journey in their company or writing effusively to Gustgen about the doings of her big brothers.

It is surprising that the Stolbergs seem to have found so little favour with Lavater, but our witness is Goethe, who came to detest the lot of them. Both Lavater and the Stolbergs – and Haugwitz, too, we presume – shared a reverence for the Genevan academic Charles Bonnet (1720–1793), then renowned, but now just another forgotten name. The deeply religious Stolbergs felt that Bonnet's theories of the development of organisms could contribute to their religious ideas; for Lavater, too, Bonnet was his 'favourite author'. There was plenty of common religious ground between Lavater and the Stolbergs, certainly more than there was between Lavater and the pantheist Goethe, but from Goethe we hear nothing of these affinities. Readers of Dichtung und Wahrheit are left with an impression of the Stolbergs – and Friedrich Leopold in particular – as mere youthful, aristocratic non-entities.

At Lavater's house Goethe met his old friend from Frankfurt, Jakob Ludwig Passavant (1751-1827), who was working as an assistant preacher for Lavater. Goethe tells us in Dichtung und Wahrheit that it was Passavant who suggested that the travellers now take a walking tour through central Switzerland. No one else in the group had ever seen high mountains.

To the mountains

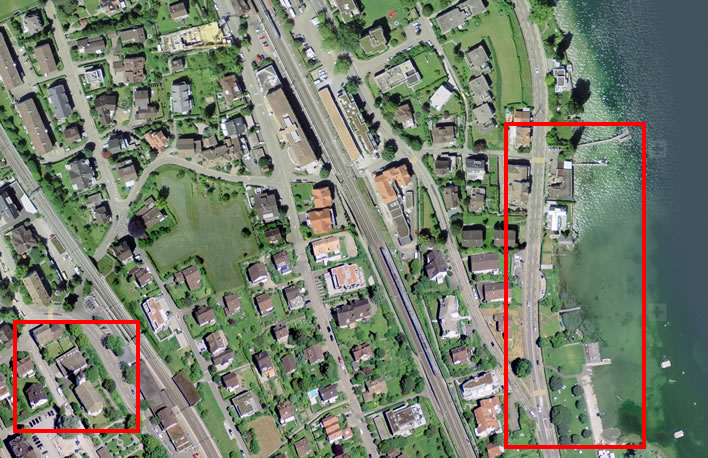

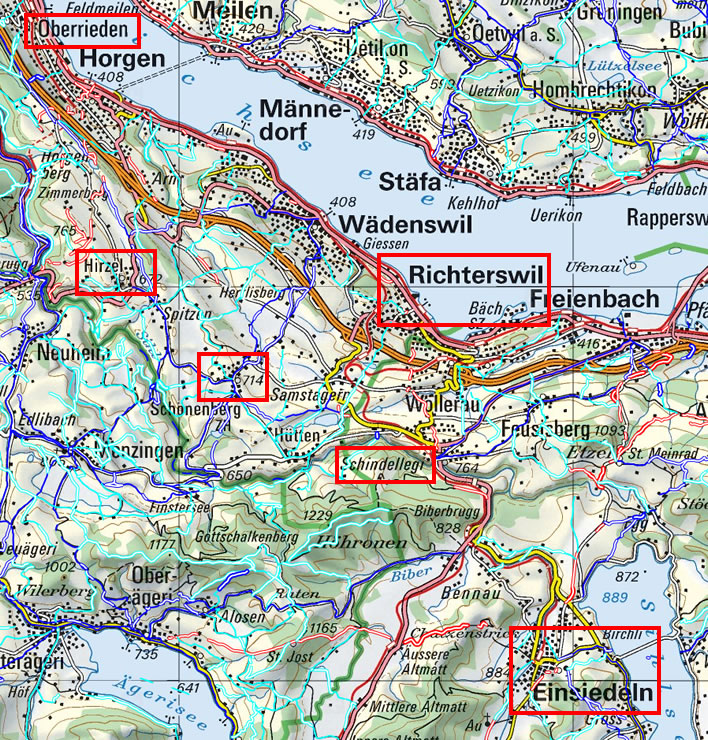

On 15 June 1775, on a 'shining morning' [Dichtung (4:18)788] Goethe, Passavant, Lavater, the pastor and theologian Johann Jakob Hess (1741-1828), Hans Heinrich Schinz (1727–1792), a lawyer and administrator in Zurich and Philipp Christoph Kayser (1755-1723), musician and composer, a friend of Goethe's from his youth now resident in Zurich set off in a rowed boat along the Lake of Zurich, They stopped at Zurich-Enge to pick up the Stolbergs and Haugwitz and were then rowed along the lake shore. After two hours they stopped for lunch in Oberrieden at the country parsonage of a friend of Lavaters, Hans Conrad Däniker (1726–1784), the first vicar of the recently built (1761) church there. The party had a 500 m walk up from the landing place to Pastor Däniker's vicarage, next to the church and the road.

An aerial photograph of Oberrieden, on the shore of the Lake of Zurich. Despite all the roads, railways (two) and houses, the church and the vicarage are still there and relatively close to their original condition (red rectangle, bottom left). One of the lakeside jetties in the red rectangle on the right would have been used by the travellers. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

Our puzzlement has already set in: the 80-year-old Goethe's description of that day in Dichtung und Wahrheit is confused and confusing. We find no mention of this pleasant lunch in Oberrieden, no mention that the Stolbergs set off from here for Einsiedeln. We only know of all this from a letter that Friedrich Stolberg wrote to his sister.

The Swiss historian Barbara Schnyder-Seidel went to some lengths to reconstruct what really happened on the journey that 15th and 16th June. [Schnyder-2 31-38] Nearly everything that Goethe wrote about this part of the journey to the Gotthard seems to have been confected from the notes dictated to his amanuensis Ludwig Geist during the 1797 journey and some other vague memories. The present piece is not the place to go through all the variants; we shall give instead a condensed, unified version of Schnyder-Seidel's reconstruction with some of our own additions.

After lunch in Oberrieden with Pastor Däniker the group split up: The party from Zurich, Lavater and friends, returned by boat to Zurich; the Stolbergs and Haugwitz walked on to the next village, Horgen, then ascended to the track that runs along the side of the Horgenberg and Hirzel, 'crossing innumerable small streams', presumably through Hirzel village, Schönenberg to Schindellegi; Goethe and Passavant went by boat from Oberrieden to Richterswil, where they landed and ascended the hillside to Schindellegi.

The journey from Oberrieden (top left) to Einsiedeln (bottom right), done one way or another. The Stolbergs and Haugwitz walked from Oberrieden to Horgen and then climbed up to one of the tracks (solid blue and hollow blue lines), probably then passing through Hirzel and Schönenberg to get to Schindellegi. Nearly all of the old routes between Schindellegi and Einsideln have been destroyed by road and rail building through the narrow gap in the hillside.

The route from Richterswil to Schindellegi is an ancient pilgrims' track; the hollow red lines mark remains of it that can be found today.

A very important pilgrims' route can be seen in the hollow red lines at the middle right of the map. This is part of the Jakobsweg, the 'Way of James', the Europe-wide pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The path runs from Rapperswil / Pfäffikon / Freienbach over the Etzel pass, past the chapel of St. Meinrad, the hermit saint associated with the foundation of the monastery of Einsiedeln, then down past the Sihl reservoir to Einsiedeln.

Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

Both groups – whether singly or together, we don't know – then went from Schindellegi to the great Benedictine abbey of Einsiedeln. It seems reasonable to assume, however, that the agreed meeting place would be Einsiedeln, not Schindellegi.

Friedrich Stolberg writes that the journey to Einsiedeln took them seven hours, which is what would be reckoned for the journey today, at a length of about 26 km with an ascent of about 760 m. Goethe and Passavant's walk from Richterswil to Einsiedeln was around 13 km and would have taken them about four hours.

As we have already noted, Dichtung und Wahrheit tells us that the full party visited Lavater's great friend, the medical doctor Johannes Hotze (1734-1801) at his home in Richterswil and that Goethe's group (at least) stayed overnight there. This cannot be true: not only does the calendar of the journey not allow this extra overnight stay, it conflicts with Stolbergs' very credible account of the journey. The clue to the solution is given in a letter from Hotze to Lavater dated 2 July 1775, which is rarely quoted in a sufficient extent:

I, too, dear man, am permanently busy and particularly so in the last few weeks. For that reason I am not able to get to Zurich. Goethe is leaving soon, however. If only I could see, hear and savour this man one more hour. [To be able] to look at this man from the hair on his head down to the soles of his feet, in all his veins, characteristics and movements, that he is the man who could write of Werther's sufferings. He left a handkerchief behind at my house, but I don't want to send it back: the memorial to his existence will stay with me.

Johannes Hotze, letter to Johann Caspar Lavater, 2 July 1775. In Johannes Hotze, 232 Briefe, 1 Beilage an Johann Caspar Lavater, 1769-1800, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Handschriftenabteilung, FA Lav Ms 514.25-256.

What can we learn from Hotze's words? The letter is dated 2 July, truly only a day or so before Goethe was to leave Zurich for Frankfurt and Lili. Since Hotze speaks of 'the last few weeks' we know that Goethe had not visited Hotze recently and certainly not following his return from the Gotthard to Zurich. Goethe was in Zurich with Lavater from 26 June to 4 July.

Hotze's use of the word 'noch', 'once more' in 'Wenn ich nur diesen Mann noch eine einzige Stunde hätte sehen, hören, geniessen können' implies, however, that Hotze had already seen him at some point on this trip. We also know that this meeting must have been at Hotze's house and not somewhere else such as Zurich, for Goethe had left his handkerchief behind in Hotze's house ('bei mir'). We can debate about Hotze's use of noch, but Hotze's possession of Goethe's handkerchief is irrefutable proof that Goethe and Hotze did indeed meet in 1775. In which case, Barbara Schnyder-Seidel's assertion that Goethe was 'on that day and no other day in Richterswil' is unsustainable.

The only possibility for this meeting is the small window of opportunity opened by Goethe and Passavant's boat journey to Richterswil on 15 June. The most likely solution is that Goethe and Passavant popped in to Hotze's house for a brief meeting on their way from the landing stage on the lake to the pilgrims' road to Einsiedeln. Hotze's property is close to the lakeside and next to the pilgims' way, so would cost Goethe and Passavant only an hour or so of delay and the busy Hotze would not have been greatly disturbed.

If we assume this, then the reason for Goethe and Passavant detaching themselves from the Stolberg group and taking the separate boat trip from Oberrieden to Richterswil also becomes clear. Lavater wished for Goethe to meet Hotze, if only briefly. Hotze was busy and had little time to spare, hence Lavater had sailed back from Oberrieden to Zurich and Passavant was left as the man who introduced Goethe and Hotze for their first meeting. Had Lavater come with them, the rules of hospitality would have extended the visit beyond the time available. Goethe and Passavant, however, had to get to Einsiedeln that evening and so Hotze's time was used frugally.

The group stayed overnight in Einsiedeln. The details of this stay – for example, where they ate and slept – are a mystery. The following morning, 16 June, Goethe and Passavant set off from Einsiedeln for Schwyz without the Stolbergs and Haugwitz. This early separation is a further mystery of this journey: was the tour of the inner Swiss cantons that Passavant had proposed in Zurich just intended for Goethe alone, or was this simply the true starting point of Goethe's Gotthard trip that Friedrich Stolberg informed us about?

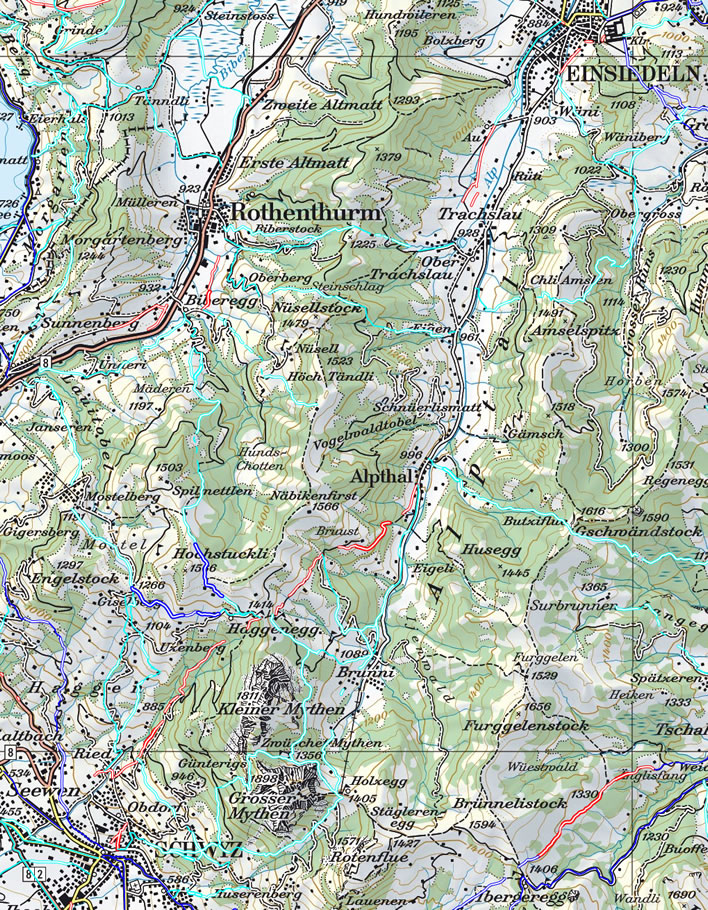

They wandered along the Alpthal another 12 km towards the striking pair of mountains that stick up in isolation, the Grosser Mythen (1898 m/6,227 ft) and Kleiner Mythen (1811 m/5,942 ft), 'these imposing irregular natural pyramids', Goethe noted.

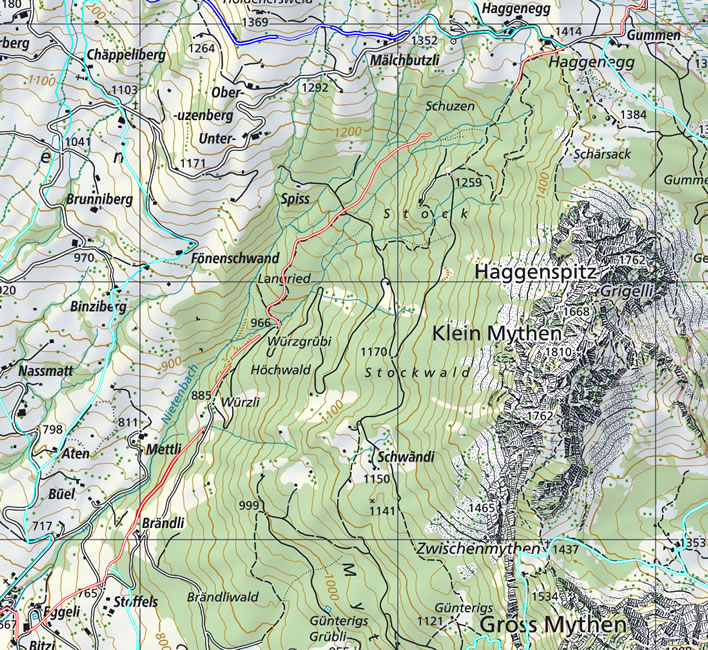

A map of the route between Einsiedeln and Schwyz. The Benedictine abbey at Einsiedeln is the notable black structure on the right of the town. The remains of the old path between Einsiedeln and Alpthal have mostly been destroyed in the building of the road. Follow the red and white line from Alpthal down to Haggenegg then around the side of the Kleiner Mythen to Schwyz. The pair found this steep and varied descent through a small gorge to be quite fun. The distance between Einsiedeln and Schwyz is about 12 km, with an overall descent of about 600 m. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

Goethe and Passavant came down the steep track from Haggenegg through the gorge around the side of the two mountains – a not unexciting descent in snow and wet weather – arriving exhausted but elated at ten o'clock in the evening in the town of Schwyz, the capital of the canton, where they fed and boozed noisily until midnight (more rowdy Germans, it seems).

A map of the descent from Haggenegg to Schwyz that Goethe and Passavant found quite memorable. The route is about 4 km long and drops about 750 m, wooded and wet – not simple in twilight or darkness.

The city of Schwyz is in the centre of the photo; behind it the landmark of the region, the two Mythen mountains. It will not surprise you to be told that the small Mythen is the one on the left and the large Mythen the one on the right. The track followed by our adventurers from Haggenegg runs to the left of the small Mythen in this picture, down the dark, tree-covered gorge. The town of Brunnen, with its harbour, is at the bottom left. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 2124 x 1780 px, 0.5MB.]. Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe, 1999.

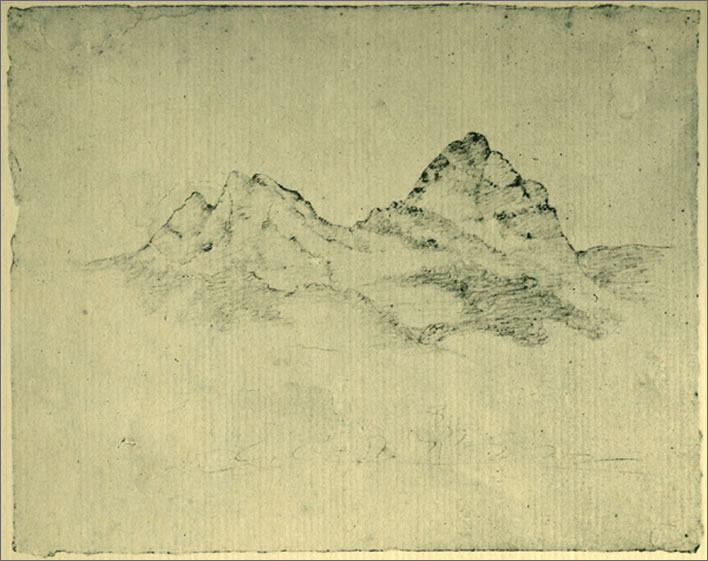

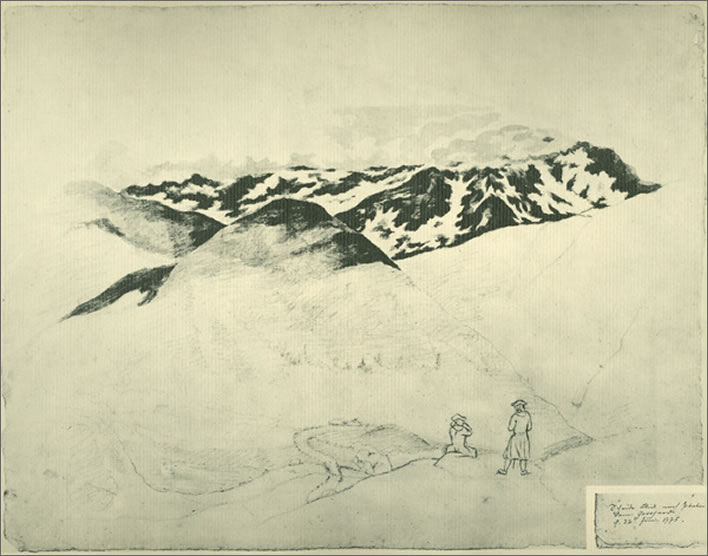

Goethe has left us a sketch, dated 17 June 1775, of the mountain pair, which he called the Haken or Haggen.

Goethe's quite accurate drawing of the mountain pair Die Mythen in Schwyz. Dated 17 June 1775. Image: Zeichnung Goethes: Die Mythen Datiert auf den 17. Juni 1775 (Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 11a; Corpus I, Nr. 107). Online.

In Schwyz they visited the neighbouring attractions, particularly the Rigi mountain on the 17th, an easy but lengthy ascent that provides a justly renowned view of the surrounding lakes and mountains. After that, Goethe and Passavant headed for the Gotthard. According to Friedrich Stolberg, writing to his sister Katharina on 20 June, Goethe could not be away from Frankfurt for long and wanted to see the Gotthard. The obsession begins.

On the 19th, Goethe and Passavant sailed along the lake past the Tellsplatte/Tellskapelle, the rock outcrop at the edge of the lake onto which Wilhelm Tell is supposed to have sprung in order to escape from his captivity in Gessler's boat. Some said that this was the spot where Tell assassinated Gessler. Whatever. The point of myths is that you can assert anything you like with complete impunity. In Schiller's Wilhelm Tell, however, this flat rock jutting out in the lake is the location of Tell's leap for freedom.

The pair landed at Flüelen and proceeded to Altdorf, at the base of the pass, 'wo Tell seinem Knaben den Apfel vom Kopf schoss', 'where Tell shot the apple from his son's head', as Goethe put it.

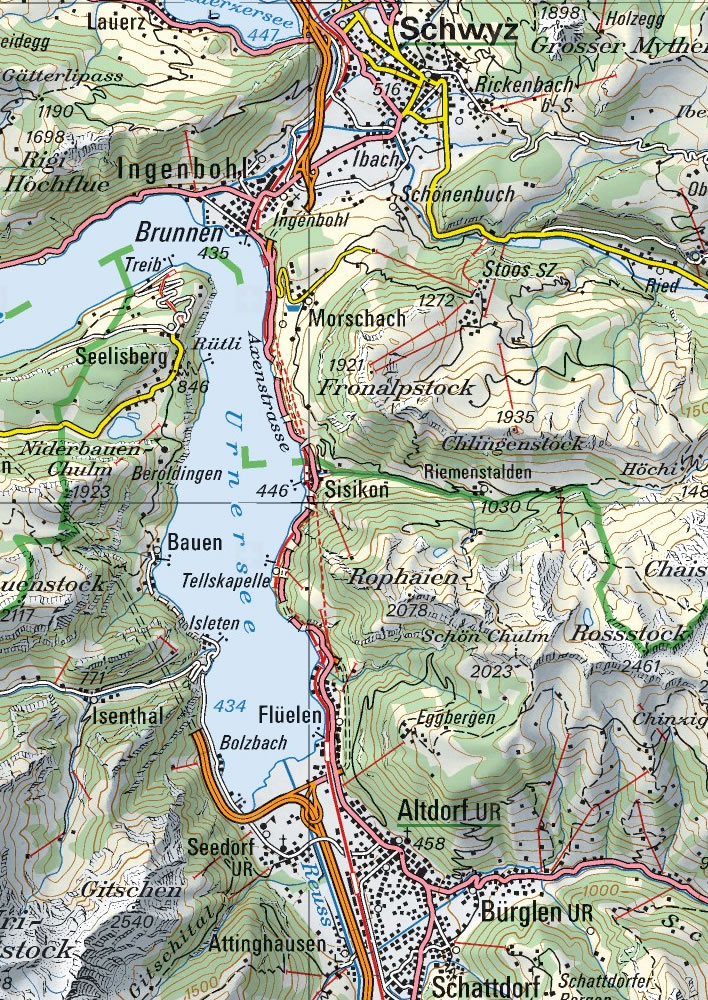

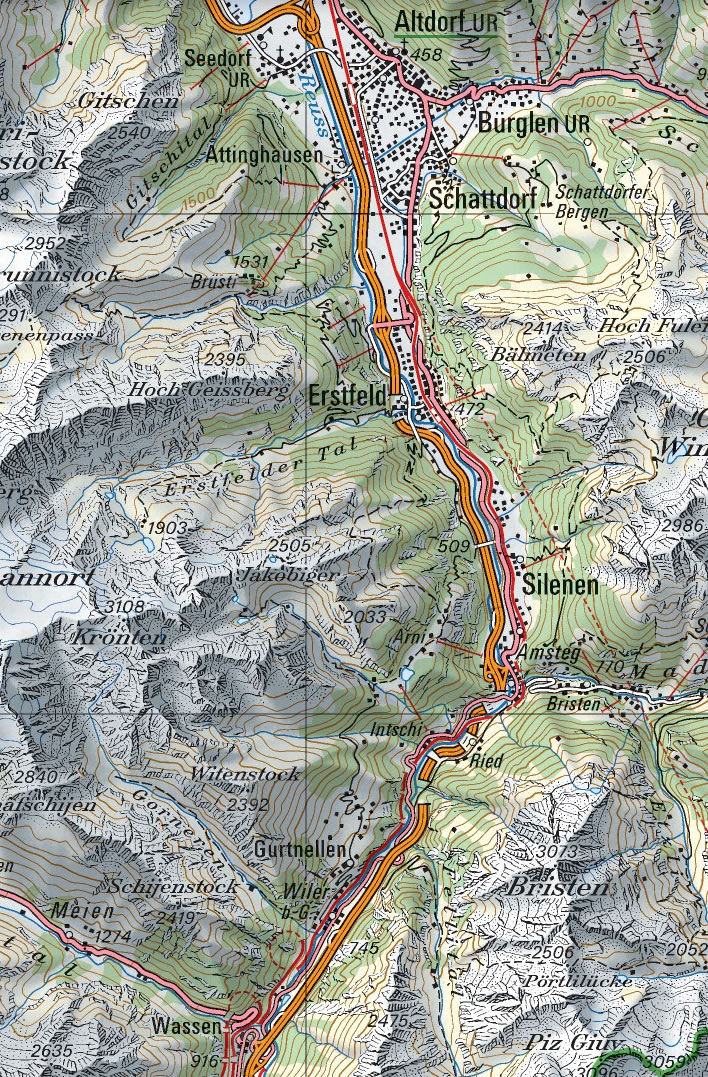

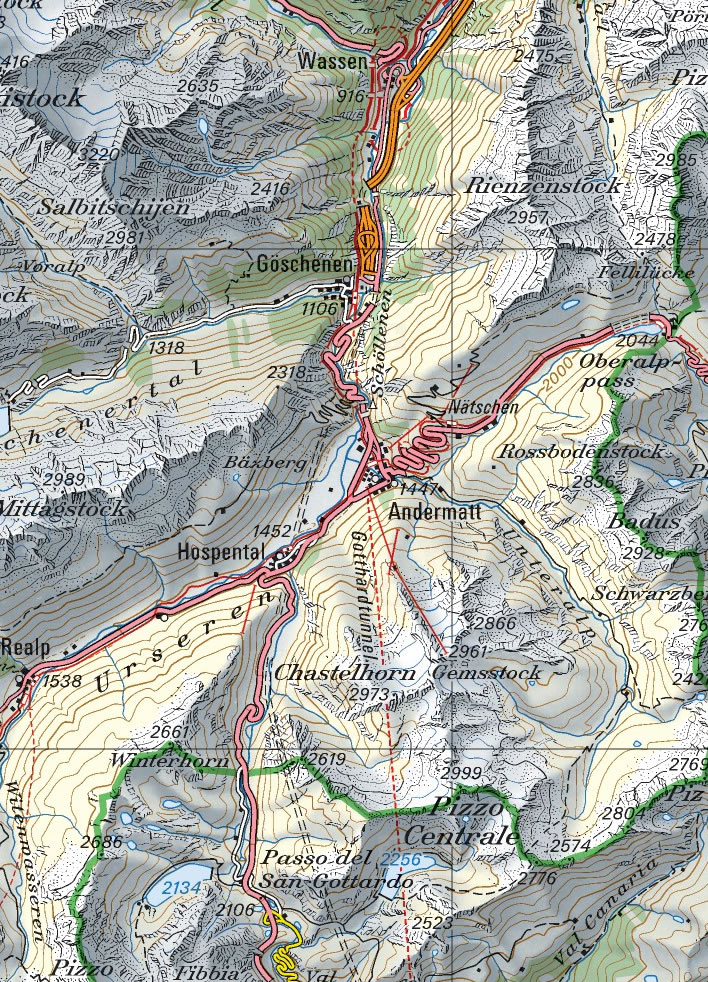

Day 1, 19 June 1775: Schwyz – Altdorf. Brunnen, Tellskapelle, Flüelen, Altdorf. c. 19 km length, 50 m descent. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

Facing the Gotthard's reputed terrors may have attracted Goethe in the same way that the tower of the cathedral in Strasbourg had attracted him. In an early example of aversion therapy he had cured his fear of heights there five years before, in 1770.

The Gotthard

Goethe and Passavant set off from Altdorf on the 20th. There was some more skinny dipping in the 'snow water' of the Reuss at Amsteg (rowdy Germans again, who shocked the moral sensibilities of the inhabitants of this deeply Catholic region, the women of which were given a view of this exuberance of German members shrivelled in ice water). They encountered pack horses, snow holes, huge pines, sheer cliffs and the deepening abyss. They arrived at Wassen at seven-thirty in the evening.

Day 2, 20 June 1775: Altdorf – Wassen. Erstfeld, Silenen, Amsteg, Gürtnellen, Wassen. c. 23 km length, 500 m ascent. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

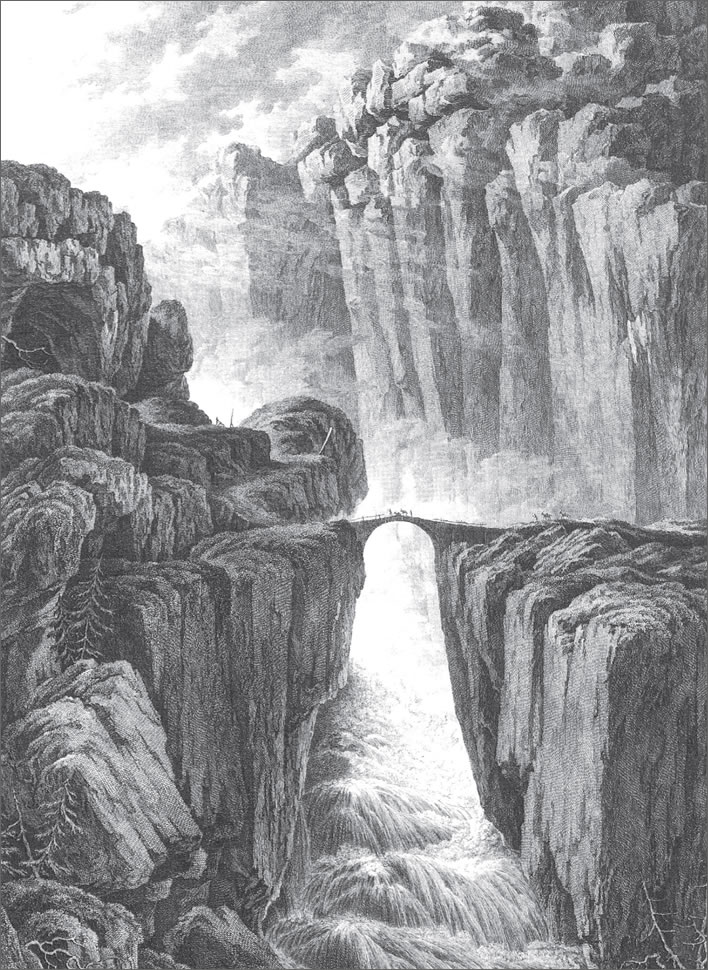

On the 21st, the day of judgment came in the Schöllenen:

'Depart 6:30. overpoweringly terrifying. Done. Drew. Desperation, struggle and sweat. Teufelsbrücke and the Devil. Sweating and fading and sinking until the Urnerloch. Exit and revived in the valley. Wonderful happy feeling and projects. In Andermatt excellent cheese. 3:25. Snow, bare rock and moss and stormwind and clouds and the noise of the waterfalls, the ringing of the pack horses. Bare as the valley of death, scattered with bones – fog – lake'.

Tagebuch-1, June.

Day 3, 21 June 1775: Wassen – Hospice. Göschenen (Teufelsstein), Schöllenen gorge (Teufelsbrücke, Urnerloch), Andermatt, Hospental, Gotthard Pass summit, Hospice. c. 19 km length, 1,200 m ascent. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

A sketch of the Teufelsbrücke by Johann Wolfgang Goethe from the first of his three journeys along the Gotthard Pass (strictly speaking four journeys, since in 1775 he went up and down the route). The representation of posts and railings in his sketch is interesting and credible, since someone in a hurry does not make such things up, whereas professional landscape artists do what is necessary to get the desired effect. Image: 'Zeichnung Goethes: Teufelsbrücke Bezeichnet: "23 Teufels Brücke"' in Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 10a; Corpus I, Nr. 127. Online.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Teufelsstein, 1775. Image: 'Zeichnung Goethes: Teufelsstein Bezeichnet: "23 Juni Teufels Stein"' in Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 9c; Corpus I, Nr. 123. Online.

The Teufelsbrücke in summer 1776, a year after Goethe crossed it for the first time. The railings that Goethe sketched are there. Plenty of drama but quite faithful to the scene, even down to the snow posts on the path leading to the Urnerloch. Unfortunately the height of the bridge has been greatly overstated. Image: Claude-Louis Chatelet (1753-1794), artist in 1776 (original lost), Louis-Joseph Masquelier (1741-1811), engraver in 1778, in Weber, Bruno. '"Aber die Kluft ist schauerlich, die sie umgiebt": elf Variationen über die alte Teufelsbrücke der Schöllenen (1595-1888) in druckgraphischen Ansichten von 1707 bis 1863'. Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol 98, 2007. Online.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, (1775-1851), The Devil’s Bridge, St Gothard c.1803–4. Lots of drama and fear. This is the bridge after the damage caused by the Russian-French engagement on the bridge in 1799 had been repaired. Image: Tate, London. Online.

The pair reached the Hospice at the pass summit. They woke early on the 22nd, with Italy at their feet and plenty of money to get them to Milan at least… and turned back:

22 June: Got up early [in the Hospice] I settled myself at the beginning of the footpath that goes down to Italy and did some drawings. […] My companion came up to me cheerfully […] We have enough money to get to Milan […] A golden heart that I had been given by [Lili] in some wonderful moments hung on the very ribbon on which she had tied it, warmed with love at my throat. I clutched it and kissed it […] Without saying another word took I took the path back from whence we had come. Hesitatingly, [Passavant] followed, he remained some distance behind me despite his affection and devotion. We joined up together again at the waterfall on the way back.

Dichtung (4:19) 799f.

This moment, the Scheideblick nach Italien, the 'farewell glance at Italy' has acquired a legendary role in Goethe's biography. That vexed question of Goethe scholarship – why did he turn back? – has filled many column inches for desperate critics with a deadline whose muse has failed to appear.

Goethe's sketch of the Scheideblick nach Italien, the 'farewell glance at Italy'. Goethe is seated and Passavant is standing. On the reverse Goethe wrote Scheide Blick nach Italien vom Gotthard d. 22. Juni. 1775, shown in the inset bottom right. Image: "Scheide Blick nach Italien vom Gotthard d. 22. Juni. 1775". Personen: Goethe, sitzend; Passavant stehend. Das Blatt ist mit Blei angelegt und z.T. mit Tusche laviert. (Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 8; Corpus I, Nr. 120; Maisak, Nr. 30). Online.

Some believe Goethe's much later assertion that he wanted to get back to Lili, clasping her token at his breast; some that he was 'not yet ready' to visit Italy, that place that would change him so much (he would finally go there in 1786), some both of the above.

However, we cynics recall Friedrich Stolberg's remark, which Goethe had made to him before he left for the Gotthard, that he had to get back to Frankfurt. [Morris 5:271] We also note that the description of the moment when he turned his back on Italy is from the appropriately named memoir written nearly forty years after the fact, Dichtung und Wahrheit, where Goethe also tells us that his friend Passavant had wanted to go to Italy with Goethe all along and had manipulated him to get him to this point. Really? There is no hint of this in his diary.

There is even more confusion, in that Goethe also tells us in Dichtung und Wahrheit that before he set off his father had recommended him to get to Italy, one way or another. [Dichtung (4:18)775] The Swiss philologist Johann Jakob Bodmer (1698-1783) wrote on 19 June that Goethe had gone to the Gotthard, with thoughts of going to Milan. This is the kind of confusion that can put food on the table of literary scholars for two centuries.

Whatever. We leave it at that, only stopping to note that for Goethe in 1775 the Gotthard was not a pass, because he didn't cross it in order to go somewhere else, it was solely a destination, just like the Rigi had been. It was a personal challenge, just like Strasbourg Cathedral had been, a challenge that, when he conquered it and proved himself on arrival in Andermatt, left him feeling sauwohl, 'as happy as a pig'.

Goethe and Passavant went back down the pass, crossed the Vierwaldstättersee and the Zugersee, returning to Zurich on 26 June and meeting up with the Stolbergs and Haugwitz once more.

Sticking it to the Stolbergs, part II

Curiously, in yet another invention from Dichtung und Wahrheit, Goethe tells us that the Stolbergs were no longer in Zurich – they had shortened their stay there in a 'strange manner'. [Dichtung (4:19)802] This is not true: he himself told Gustgen at the time that he parted from them in Zurich to return to Frankfurt; they were certainly all present in a meeting of the 'Physical Society' in Zurich with Lavater on 26 June. [Morris 5:272] Stolberg tells us that they and Goethe and Lavater all met up for the 'whole afternoon' on 30 June. [Morris 5:273]

Yet more knifing of the Stolbergs comes a short while further on in Dichtung und Wahrheit when Goethe tells us more about the 'strange circumstances' that led to the Stolbergs and Haugwitz leaving Zurich in such haste.

According to Goethe, the Stolbergs lived up to the reputation that the rowdy Germans have among the Swiss with a bout of noisy skinny-dipping in the Sihl river near Zurich, which ended in stones being thrown at them from the bushes on the bank by the outraged locals. [Dichtung (4:19)803]

But, being factual for a moment, the Stolbergs, Haugwitz and Goethe, too, were all fans of cold, open air bathing for their health's sake. You only have to look at the markedly rosy cheeks in the portrait of the later Friedrich Stolberg to see that this was true.

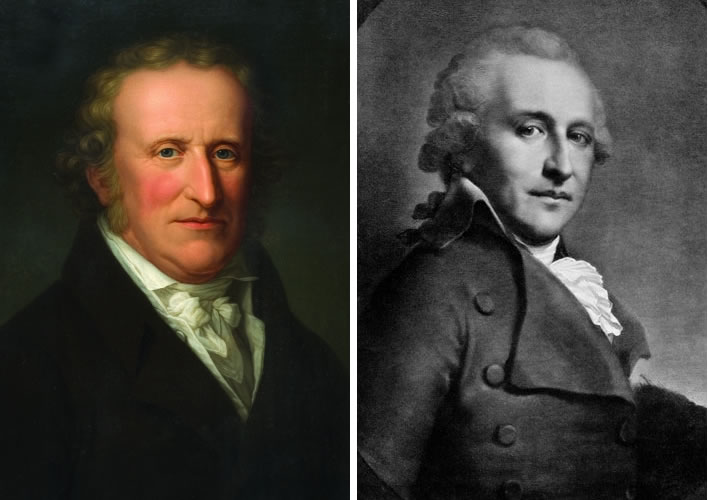

Graf Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg

Left: Portrait by Friedrich Carl Gröger, 1818? Right: Stolberg? Unknown source, ND.

Goethe adds that the scandal of such behaviour on the part of people who were associated in some way with Lavater, a religious eminence in Zurich, caused him 'umpleasant consequences', which were only finally resolved when the 'meteoric travellers' finally departed. All of it apparently Goethe's Dichtung, 'invention'. This part of his memoirs was completed in 1830, by which time Friedrich Stolberg had been dead ten years (1819), and was only published in 1833, shortly after Goethe's death.

Or perhaps Goethe's calumnies against his travelling companions were quite deliberate, or the result of some deep Freudian process in the old man or simply a case of that tasty dish, revenge, being eaten cold. Goethe – whether as pantheist or atheist or whatever he was – came to think ill of the pietist fervour of the Stolbergs and Haugwitz. A tale that has them fleeing Switzerland to escape religious prejudice because of their closeness to natural innocence in naked bathing is quite delightfully vicious. [Dichtung (4:19)804]

However, there seems to be a grain of truth behind the story, since a similar tale about the Stolberg's is also reported in 1779 by Johann Georg Zimmermann (1728-1795), the renowned writer and doctor. Zimmermann was a close friend of both Lavater and Hotze; Hotze was the doctor who saved the life of Zimmermann's son in 1778. We therefore have no reason to disbelieve his account.

According to Zimmermann, the Stolbergs' and Haugwitz's bathing antics met with some concern during their time in Switzerland; a disapproval that even involved Lavater. However, the issue was less nudity but that the men were taken to belong to the Anabaptist sect, enthusiastic open-air baptisers of adults. [Zimmerman 57] A similar tale is recounted in a letter from the Stolbergs friend Johann Heinrich Voß (1751-1826). One version of the story has Lavater on the riverbank, talking to the young men during their bath, which led the locals to interpret the scene as Pastor Lavater trying to convert some Anabaptists back to the true religion.

Naked bathing, in decent circumstances, did not carry any stigma at that time. The Swiss, a clean people, were always happy to dip themselves into their greatest natural resource. It is telling that Zimmermann, unlike Goethe, nowhere implies that prudery was a factor. Zimmermann made his name by writing pieces explaining science to the masses, so it is no surprise that most of his piece extols the benefits of the cold dip.

In contrast, Zurich, one of the centres of the Anabaptist movement, had a dark history in the 16th and 17th centuries for torturing and martyring them. As it happens, there is memorial to Anabaptists executed by drowning in the Limmat in Zurich only a few steps from Zum Schwert, the hotel where the young men stayed on their arrival in the city.

But, whatever the truth of the matter, the Stolbergs and Haugwitz certainly did not have to flee Switzerland in haste. We do know that Friedrich Stolberg wrote to Lavater apologising for their wild behaviour in the spa at Pfäfers in Canton St. Gallen (near to Bad Ragaz, the place where the rich go to natate today) – not Zürich. Historical truth? That most ubiquitous historical source: Chinese whispers.

Finally, to round off this silly digression about cold baths, we note that Goethe and Passavant put on their own performance in Amsteg, much to the fright of the locals, so to blame the Stolbergs and Haugwitz for doing the same thing is hypocrisy.

We should ignore the venom of the 80-year-old Goethe and do our best to be fair to the Stolbergs. Although we have focused on Goethe and the Gotthard, the Stolbergs and Haugwitz had their own intellectual preoccupations in Switzerland. They were not simply young aristocrats having fun in foreign parts.

As we have already noted, the Stolbergs were great admirers of the Swiss naturalist Charles Bonnet, who lived in Genthod, Geneva. Bonnet, now almost forgotten, was one of the most famous naturalists of the time, with a European following. The Stolbergs and Haugwitz were deeply religious and thoughtful young men, who hoped to use Bonnet's theories of natural development as part of a Christian interpretation of the development of the soul. They made the journey to Geneva to see Bonnet, reached his country mansion but could not pluck up courage to disturb him. These are the arrogant aristocrats who, Goethe tells us, forced themselves unintroduced onto Lavater.

Back home, finally

Once back in Zurich Goethe stayed with Lavater again, this time for a full eight days: the urge that he told us about in Dichtung und Wahrheit that had overwhelmed him on the summit of the Gotthard Pass, the urge to rush back to Lili, seems now to have evaporated – perhaps he loved Lavater more. Or Gustgen, the pretend pen-sister he never met.

He left Zurich for Frankfurt on his own on 4 July, leaving the Stolbergs and Haugwitz behind once more to undertake a mountain hike together – a 'cloud bath' he called it to Gustgen. The Stolbergs left Zurich on 5 July.

Goethe travelled to Strasbourg and thence back to Frankfurt on 26 July – yes, 26 July, 22 days later. In the desperate rush back to Lili, the love of his life, he dawdled here and there, stayed in Darmstadt for a while with Merck and the Herders before the entire party finally returned to Frankfurt on 26 July.

The elderly Goethe's reshaping of the 1775 journey to the Gotthard in order to put at its centre his love for Lili is simply eine Dichtung, an invention. The idea is absurd: as though Romeo took a month off after the night of passion with Juliet to go for a sightseeing tour to Naples. But then, Goethe believed that empirical reality was really just a substratum – base stuff that was refined into 'truth' by some artistic process that took place in the head of the genius. When someone believes that, there is no hope for them as narrator, historian or scientist. You cannot believe a word they say.

Anyway, a life with Lili was not to be: there were a few painful, hopeless months until the engagement was finally broken off. There was even a plan to run off with her to the young American states, but Lili was cool and knew well how to play her Werther-Romeo.

As if his dawdling return was not in itself enough evidence to destroy Goethe's self-propagated Lili-thesis, there is one further witness that we have to hear: Goethe's indulgent and long-suffering father. As far as his italophile father was concerned, Wolfgang was going to Italy and it was for that purpose that he had been sending him money. In Dichtung und Wahrheit the wanderer himself hints carefully but dismissively at his father's annoyance. You always know when Goethe is creating one of his inventions when his syntax becomes difficult to untangle, but the sarcasm of the last sentence is unmistakeable:

[I] found myself in Frankfurt once more, well received from everyone, even from my father, who did not openly express his annoyance but made it tacitly plain that not only had I not descended to Airolo and reported to him my arrival in Milan but especially that I could not produce the least bit of evidence of the experience of wild cliffs, seas of mist and dragons' nests. Not in direct contradiction, but from time to time, he let the basis of his thought be known: who had not seen Naples, had not lived.

As with Friederike five years before, Goethe, never a man for commitment, got over his broken heart. In November 1775, at the invitation of Duke Carl August of Weimar (1757-1828), Goethe tells us that he finally bade Lili a proper farewell and left for Weimar and new beginnings. [Dichtung (4:20)831] With Friederike in Sesenheim, Charlotte Buff in Wetzlar and now Lili in Frankfurt, Goethe's solution was his great speciality: make himself scarce – hit the road, Wolfgang!

Update 19.11.2017

Three images added: an illustration of the Hotel zum Schwert around 1500; two photographs of the Haus zum Waldries, Caspar Lavater's rooms in Zurich where Goethe stayed.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!