The Poetry Bookshop 1913-1935

Posted by Richard on UTC 2018-07-17 07:43 Updated on UTC 2019-01-06

A short while ago we looked at the artistic uproar in London in the febrile years before the Great War, stirred up initially by Marinetti and the Futurists, followed by the 'counter attack' of the Vorticists and Blast.

Although the troublemakers themselves were happy to tell us of the impact their respective movements had, they were not the only literary phenomenon in London at the time. There was another, much quieter but much more long-lasting phenomenon: the Poetry Bookshop.

By virtue of its physical presence, its sales, its publishing activities and its relative longevity it had much more impact on literary life in London in the first quarter of the 20th century than most of the literary magazines and the literary movements of the time.

It was officially opened on 8 January 1913 and it kept going through the war years and the turmoil of the twenties. It closed its doors in 1935, after just over twenty-two years. The Great War, the Russian revolution, the influenza epidemic, the hardships of the post war years, the missing generation of men, the roaring twenties and the golden youth who had been too young for the great reaping, the share crash of 1929 and the depression that followed it, the fascist turmoil in Italy and the National Socialist turmoil in Austria and Germany – all these great events washed over it. It saw Futurism, Vorticism, Dada, Cubism, Modernism and so on – all in those twenty-two years.

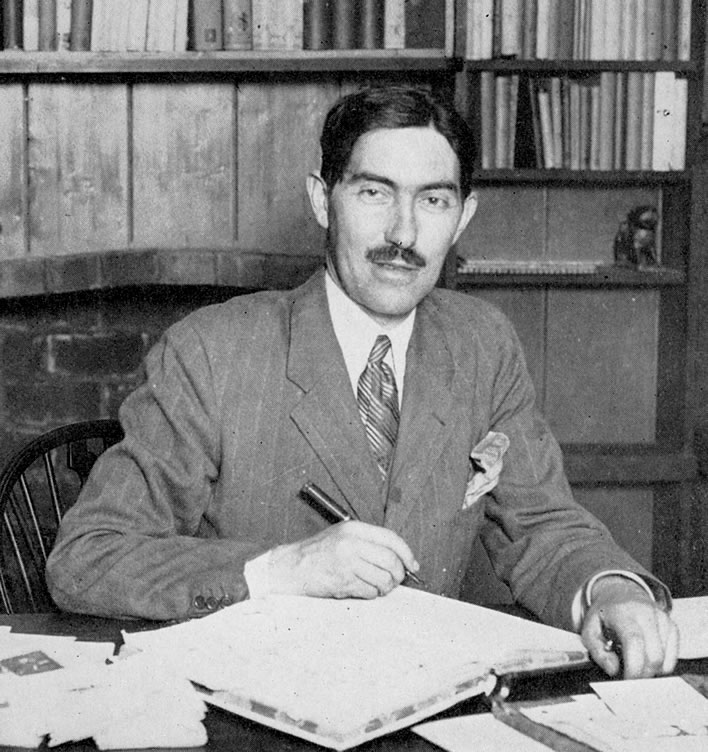

The man who founded it, Harold Monro (1879-1932) kept it going through the force of his own personality and the depth of his own pockets. He was spurred on by his belief that poetry was inherently a Good Thing. He wouldn't see the end of the bookshop – he died on 16 March 1932 – but his widow, an equally dedicated spirit, kept it going for another three years.

Harold Monro photographed in the Poetry Bookshop in 1926. Image: Joy Grant, op. cit.

The Poetry Bookshop was set up in a house in 35 Devonshire Street [now Boswell Street] off Theobalds Road. Devonshire Street at that time was still a slum area – the contrast between the Bookshop's rough, working-class surroundings and the gentle, thoughtful jewel that had been set there struck many visitors who were brave enough to make their way past the pubs and tenements of Devonshire Street. People who cared about poetry would make the effort, remarked Monro on one occasion.

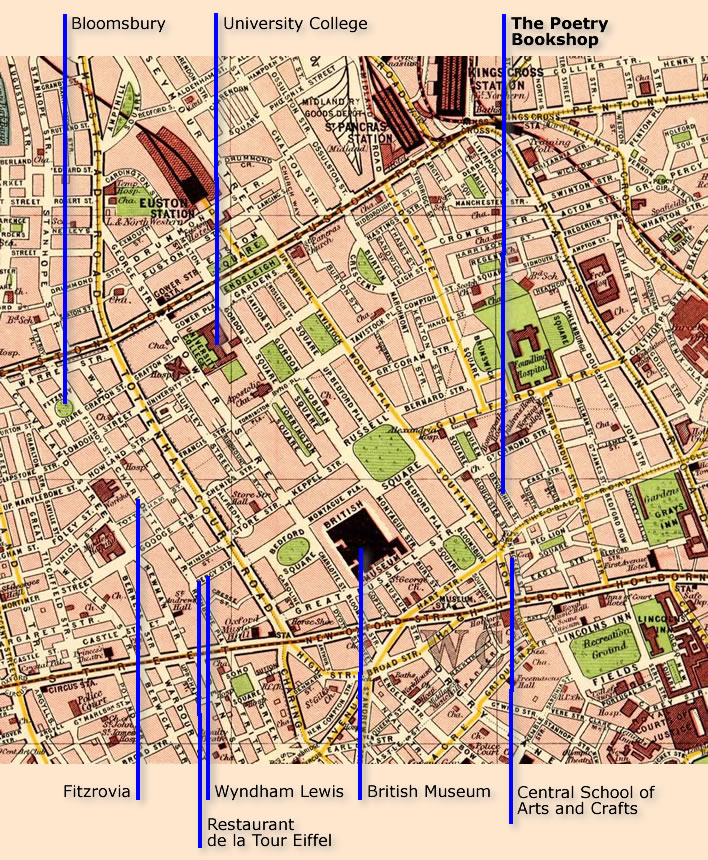

The general location of the Poetry Bookshop was spot on, however. It was at the heart of literary and artistic London: a near neighbour of the British Museum and close to University College, King's College and the then Central School of Arts and Crafts, the child of William Morris and John Ruskin. A few steps away were localities that became associated with artistic movements: Bloomsbury and that modern invention, Fitzrovia.

Literary London on the basis of a street plan from 1900. For clarity we have only added a few of the principal locations – many others are possible. Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia are only vague pointers to ill-defined areas. Virginia Woolfe lived in Fitzroy Square; Bloomsbury Square is between the British Museum and the Central School of Arts and Crafts. The Fitzroy Tavern in Charlotte Street allegedly gave its name to 'Fitzrovia'. The location of the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel and Wyndham Lewis's flat (both in Percy Street) have been added as associations with Blast. King's College London is just off the south of the map and has not been marked. To the east and south-east of the Poetry Bookshop are the various inns of court, which were also a source of customers for the bookshop. Image: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

The bookshop

The Poetry Bookshop was about as far removed from what moderns conceive as a 'bookshop' as one can get. There were indeed books on shelves, but there were tables with copies of the latest journals, chairs and benches, a crackling fire in winter and the occasional cat and dog. No one was pressured to buy, browsing and reading was considered to be normal and the staff would give generously of information without expecting an accompanying purchase.

The homely atmosphere was quite considered. Monro called on the cabinet maker Arthur Romney Green (1872-1945) to furnish the shop with bookshelves, tables and benches. Romney Green had a carpentry studio in Hammersmith Terrace and he was deeply involved with the vibrant London Arts and Crafts scene of the time. Green was a follower of William Morris (1834-1896) and a friend of Eric Gill (1882-1940). He was also a lifelong scribbler and poet, much influenced by Morris. He published a book of his poetry in 1926, Twenty-one Sonnets, and put together an anthology A Craftsman's Anthology, which was only published three years after his death.

Green's products were weighty constructions out of solid oak, entirely made by hand – a nightmare for removal men. Although his pieces still fetch good prices from collectors, he, his work and his poetry are largely forgotten now. Green was a lifelong socialist, certainly not a greedy man, but we have to recognise that Monro must have invested a lot of money in his dream – the homely atmosphere in the Poetry Bookshop was dearly bought.

The Poetry Bookshop was also a real home to a number of writers: at the top of the building were two tiny attic rooms that Monro rented out at low prices, generally to needy poets. Wilfred Owen, Wilfrid Wilson Gibson and Robert Frost were among those who stayed there.

The publishing house

The Poetry Bookshop had turned into a poetry publisher even before it was opened – and it did so with a bang: its first publication, Georgian Poetry 1911-12, became an astounding bestseller, as did all the subsequent editions that followed it.

The idea for the anthology came to Rupert Brooke and Edward Marsh on the evening of 19 September 1912. Marsh contacted Harold Monro the very next day and the book was published just before Christmas of that year. Its success was of course excellent publicity for the opening of Monro's Poetry Bookshop the next month.

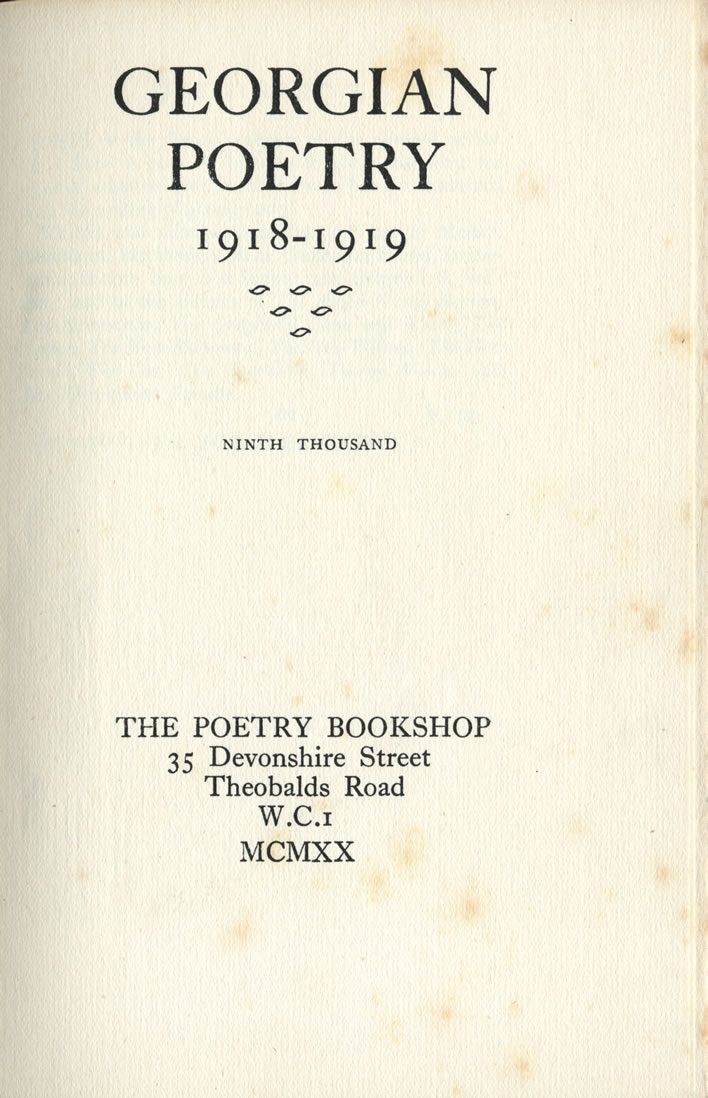

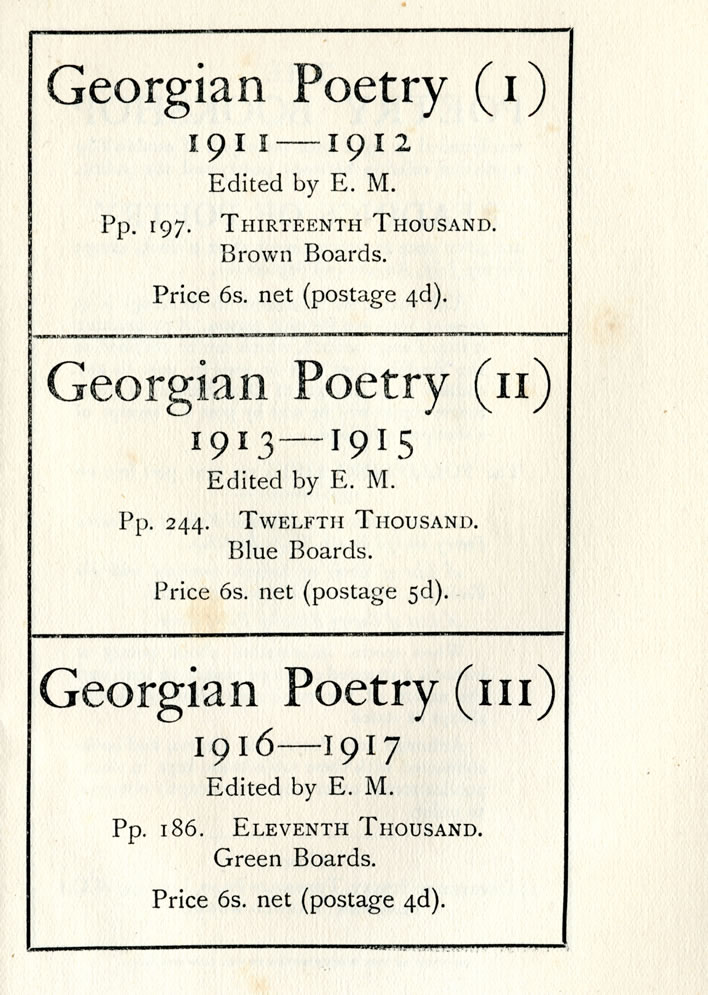

Five hundred copies (at 3s.6d. each) had been printed and were all sold shortly afterwards; by the end of 1913 the book was in its ninth thousandth printing. Five volumes in the Georgian Poetry anthology series were produced in all, at roughly two-yearly intervals, even throughout the war years (1912, 1915, 1917, 1919 and 1922 for the punctiliious).

Cover and title page of Georgian Poetry 1918-1919. Images ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

Monro's extremely altruistic dealings with money – which we have already seen in his management of the bookshop – were also applied to the publishing sensation Georgian Poetry. According to Monro's biographer, Joy Grant, based on information from Monro's wife, Monro took the financial risk of publishing the works almost entirely upon himself. He would have personally lost the cost of production had the book failed. In return he received the standard bookseller's commission of 10 percent on each copy sold (raised in 1919 to 15 percent) and received his share of the profits as a contributor to the contents.

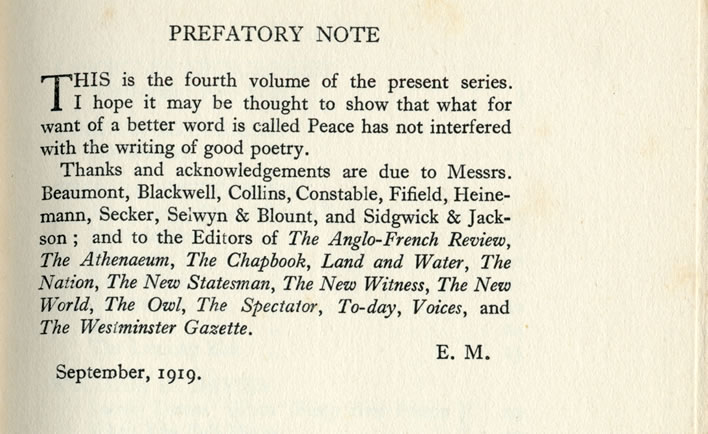

Edward Marsh's prefatory note to Georgian Poetry 1918-1919 Difficult to understand is the convoluted remark 'I hope it may be thought to show that what for want of a better word is called Peace has not interfered with the writing of good poetry'. Your guess is as good as mine. Image ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

Advertisement for preceding issues of Georgian Poetry with print run figures. Image: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

Some financial aspects of Georgian Poetry strike the less altruistic modern as bizarre. All profits – and they were considerable – were divided equally between all contributors regardless of how many poems they had contributed. Solidarity gone mad. Edward Marsh was clear about Monro's role: without him the Georgian Poetry anthologies would have never appeared.

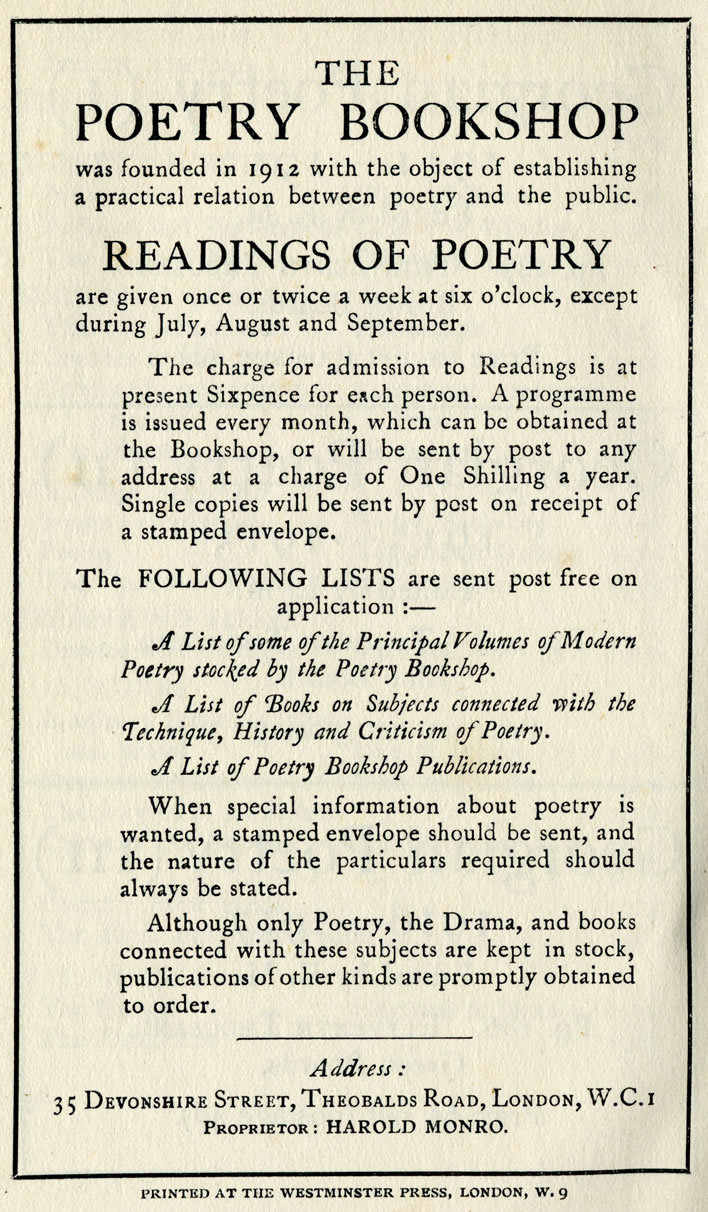

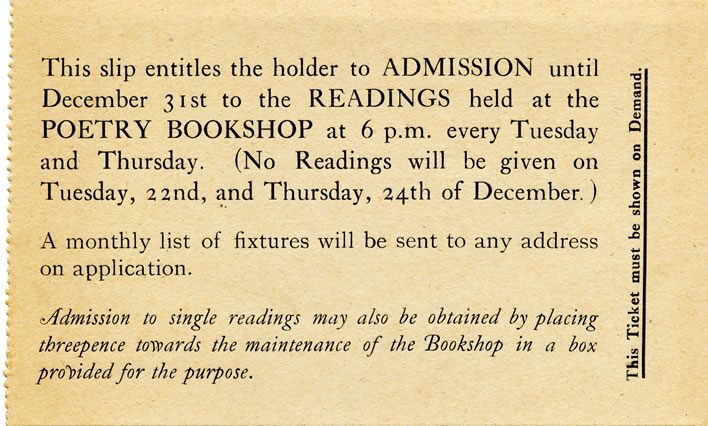

Harold Monro's advertisement for the Poetry Bookshop that appeared in Georgian Poetry 1918-1919. This advertisement appeared during the period when the admission fee had been increased from threepence to sixpence. The price increase had a serious effect on attendance and was reversed quite soon after its introduction. We conclude: There is a value that can be put on a poet's reading of his works and it seems to be about threepence. Image: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

It is remarkable that, despite the enormous success of Georgian Poetry, Monro seems to have kept his distance from the 'Georgians' as a movement. We may see that what we called his altruistic financial involvement in publishing the anthology was really a sign of publishing independence. Had he offset his considerable risk with a participation in the profits of the publishing bestseller he would have made considerable sums but he would have been bound to the layer of golden eggs from thence onwards.

In fact, his next publishing venture was quite contrary and as much a financial disaster as Georgian Poetry had been a success: Des Imagistes. This was an anthology put together by Ezra Pound and the group of radical young poets around him – Aldington, Flint, Lowell, Joyce – as a counter-attack on the Georgians.

More imagist publications followed: Aldington's Images and Flint's Cadences, both of which Monro published, both loss-makers, both acts of financial altruistism in the cause of poetry.

Yet, it is interesting that when presented with the opportunity to publish T.S. Eliot's remarkable poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock– arguably the greatest poem of the 20th century – Monro declined the opportunity: it (and some other works of the time) were a modernist step too far for him. He has thus become in the eyes of history – and which other eyes matter? – the man who published the Georgian poets but who baulked at the tide of modernism which was about to sweep over English literature. That is unfortunate and unfair for such an eclectic promoter as Monro. Although a third rate poet himself he was more open minded than most and, let's face it, a man with such an altruistic wallet earns the right to pick and choose his hobby horses.

Monro was a busy publisher. He had started up The Poetry Review in January 1912, a year before opening the Poetry Bookshop. The magazine now took up the first floor of the building. Another Monro venture, the quarterly journal Poetry and Drama brought out eight issues from March 1913. In addition there were occasional publications such as chapbooks and 'broadsides'. Even during the war years, when Monro was a serving officer, the Bookshop kept going, run by his extremely able assistant Alida Klementaski, whom he later married.

Poetry readings

But the most notable thing about the Poetry Bookshop was its most ephemeral aspect: the regular poetry readings that were held there. The readings, which were held throughout the whole 23-year existence of the bookshop, were an innovation for their time.

These days poetry readings are commonplace and completely unexceptional – poets who may never get their work published anywhere have plenty of opportunity to read it all over the place; this was not the case in 1913.

Not only was there no existing audience for such events, the poets themselves had to be won over to the performance of their works. Some refused; some were paralysed by stage-fright; of those who did manage to read their own or others pieces, most were terrible performers. A few were good, and a very few were stars. William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) was one of the latter. We are not surprised, because his verse was composed orally in the first place – he had a fine ear for the music of language.

… at first five or six people would come and listen in a room upstairs, then ten or fifteen would attend readings in the offices behind the shop; by the end of 1913, at seventy readings held, the average attendance was twenty-seven; in March 1915, after two hundred readings, Monro estimated that the attendance had averaged about thirty-five.

[Grant 75]

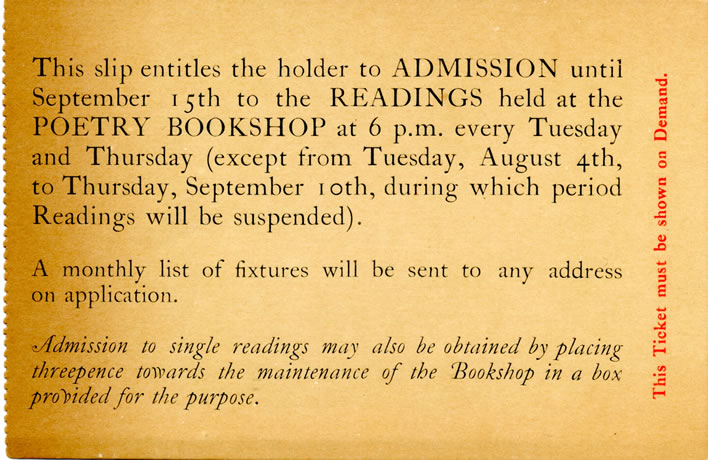

The readings began at half-past five or six p.m. Out of consideration for the powers of endurance of the audience they lasted on average about thirty-five minutes. They were held twice-weekly, on Tuesdays and Thursdays until 1915, then after that only on Thursdays. They were not advertised apart from in the shop.

Season tickets to the summer and spring semester of readings at the Poetry Bookshop in 1914. Unfortunately I have no idea what such a series ticket cost. Images: ©Figures of Speech (link to article if reproduced).

Until March 1913 the reading room was on the second floor of the building. After that Monro used an old out-house at the back of the shop that could accommodate sixty or seventy people. Here is one recollection of those readings as they were before the war. The audience gathered in the bookshop:

One looked over the walls with their rough rime sheets nailed up (they were decorated with antiquarian woodcuts), one fingered the books on the shelves: or else one just fidgeted about till the hour struck. Half by accident, so it seemed, one became aware that the presiding genius – Mr. Harold Monro – had pushed aside the curtains at the rear and was standing there with stiff little soldierly bows and a slight wave of the hand – just the faintest suspicion of a smile working round the corners of his impassive, swarthy, as it were half-oriental face – standing there, inviting entrance into the sanctum.

People passed under the curtain, beyond a crooked corner, and along a passage with whitewashed plaster walls. Then I think there was another turn – and this time, under a part of the ceiling open to the sky (one felt a few drops of rain in wet weather, anyway), and so up the narrow staircase, out of the candlelight into the reading room. There was something like a small village meeting-house in its ensemble, –the seats arranged in rows, –the windows curtained with green –and the white plaster walls broken by diagonals of black beams.

All was in semi-darkness, lit only by a shaded lamp over against the reading-table, in a little space set in the far end of the room. The seats would fill rapidly … There was a short pause… Then the person who was to read came up the ‘middle aisle, took his or her place at the desk, and so started.

[Grant 76f]

The occasion was atmospheric, to say the least. At the early readings there was not yet any electric power and so readings were performed by candle light or in the aura of an oil-lamp with a green shade, which cast dramatic shadows across the reader's face.

We have an account of one of Yeats's masterful readings, his keening invocation of ghosts and spirit riders perfectly suited to the séance-like atmosphere of the room:

I can still vividly remember the time Yeats read at the Poetry Bookshop. Spring was in the air, and the lady in front of me – I think she was young – anyhow she had a large bunch of sweet smelling purple violets. The dark curtains were drawn across the windows and the room was in darkness except for the golden light shed on the reader’s table from the two slender oak candle-sticks. From the workshop next door came the muffled beat of the gold-beaters’ mallets.

A ripple of expectation ran through the packed audience, then a deep expectant hush as the poet stood silent for a moment framed in the candlelight against the dark curtain, a tall dark romantic figure with a dreamy inward look on his pale face. He began softly, almost chanting, 'The Hosting of the Sidhe', his silvery voice gradually swelling up to the solemn finale. No one moved, waiting for him to continue. I cannot remember how long he read – all lyrics – some sad, some gay, some tragic, varying the pitch and tone of his voice to suit the mood, weaving a spell over his listeners.

[Grant 77f]

It takes little effort to imagine Yeats chanting this out in a half-lit room – to the ghostly rhythm of ghostly hooves:

The host is riding from Knocknarea

And over the grave of Clooth-na-bare;

Caoilte tossing his burning hair,

And Niamh calling Away, come away:

Empty your heart of its mortal dream.

The winds awaken, the leaves whirl round,

Our cheeks are pale, our hair is unbound,

Our breasts are heaving, our eyes are agleam,

Our arms are waving, our lips are apart;

And if any gaze on our rushing band,

We come between him and the deed of his hand,

We come between him and the hope of his heart.

The host is rushing 'twixt night and day,

And where is there hope or deed as fair?

Caoilte tossing his burning hair,

And Niamh calling Away, come away.

Yeats, William Butler. 'The Hosting of the Sidhe', The Wind among the Reeds (1899) in Collected Poems, Macmillan, London, 1965, p. 61.

Yeats composed orally – 'wrote' is not quite the right word. The most famous witness we have of this is Ezra Pound (1885-1972), who spent three winters (1913-1916) in a kind of artistic retreat with Yeats at the isolated Stone Cottage near the village of Coleman's Hatch in Sussex. Pound recalled Yeats's oral composition technique more than thirty years later during his confinement in the prison camp in Pisa after his capture by the American forces in 1945:

so that I recalled the noise in the chimney

as it were the wind in the chimney

but was in reality Uncle William

downstairs composing

that had made a great Peeeeacock

in the proide ov his oiye

had made a great peeeeeeecock in the…

made a great peacock

in the proide of his oyyee

Pound, Ezra Loomis. The Cantos of Ezra Pound, Faber & Faber, London, 1975; 'The Pisan Cantos' (1948), Canto 83, p. 533f.

The passage that Pound recalls was published in Yeat's volume Responsibilities in 1914, so he would indeed have been composing it in that first winter at Stone Cottage. Here it is in bleak, silent text that will come alive if you read it aloud:

What's riches to him

That has made a great peacock

With the pride of his eye?

The wind-beaten, stone-grey,

And desolate Three Rock

Would nourish his whim.

Live he or die

Amid wet rocks and heather,

His ghost will be gay

Adding feather to feather

For the pride of his eye.

Yeats, William Butler. 'The Realists, II The Peacock', Responsibilities (1914) in Collected Poems, Macmillan, London, 1965, p. 135f.

Yeats's fame and popularity as a reader would mean that, along with a few other speakers such as Ford Madox Hueffer (1873-1939) and Walter de la Mare (1873-1956), Monro had to hire a larger hall. The favourite was the Artificers' Guild Hall in Queen Square, just at the top end of Devonshire Street. Marinetti's performance – commensurate with his Futurist superstar status – took place in Clifford's Inn. A reading by the actor Henry Ainley (1879-1945) even pulled in an audience of three hundred.

Rupert Brooke

We can trace the progress of Rupert Brooke from unknown to poetic superstar, propelled by the Georgian Poetry rocket, by the number of listeners he obtained at the two readings he held in the Poetry Bookshop. He came frequently to the Bookshop, where he would often sit surrounded by the many admirers of ' the most beautiful man in England'.

At his first reading, on 28 January 1913, he read from Swinburne and Donne to all of six people. At his second reading, in July 1914, scarcely 18 months later, he drew in a packed house of around seventy people. Brooke had been struck down with a cold and the reading was unsurprisingly a disaster.

He came in and gave me his hand and told me he dreaded the thought of having to perform. After he had read a line or two in a low voice, an old lady in the front row who carried an ear-trumpet exploded, 'Speak up, young man!'

[Grant 81]

The American writer Amy Lowell (1874-1925) was also present on that evening and wrote an acerbic review of the occasion in The Little Review:

A month ago I toiled up the narrow stairs of a little outhouse behind the Poetry Bookshop, and in an atmosphere of overwhelming sentimentality, listened to Mr. Rupert Brooke whispering his poems. To himself, it seemed, as nobody else could hear him. It was all artificial and precious. One longed to shout, to chuck up one’s hat in the street when one got outside; anything, to show that one was not quite a mummy, yet.

[Grant 85] Original in Lowell, Amy. 'A Letter from London, 28 August 1914' in Little Review, I, September, Vol 1, No. 7, October 1914 p. 6. [17.07.2018: issue data corrected and quotation concluded correctly.]

The modern reader may well agree with Lowell that these poetry readings were 'artificial and precious'. It would after all be only a few months before the blood and body parts ejected from the meat mincer of the Great War gave us a new term: 'War poetry'.

Perhaps 'artificial and precious' might be applied to the entire venture of the Poetry Bookshop. But Monro's venture was well-meant and harmed no one but himself and no thing other than his bank balance. Many writers profited from their association with Monro and his bookshop. His hobby horse was indeed a Good Thing.

Harold Monro died a lonely alcoholic on 16 March 1932 after a lengthy and distressing illness. He felt abandoned by the many artists he had supported and published; his reward for his altruism was obscurity.

Sources

| Grant | Grant, Joy. Harold Monro and the Poetry Bookshop, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1967. |

Update 06.01.2019

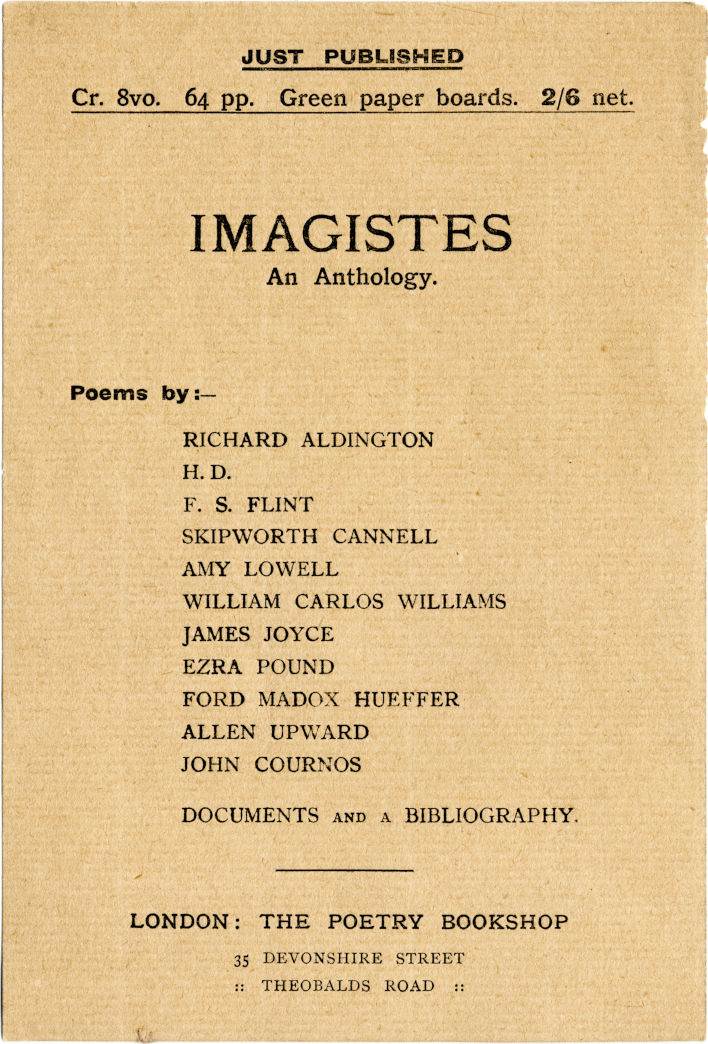

From the Figures of Speech archives, a Poetry Bookshop flyer for the first British edition of the groundbreaking anthology Des Imagistes.

Image: ©Figures of Speech, reuse only with link to this page.

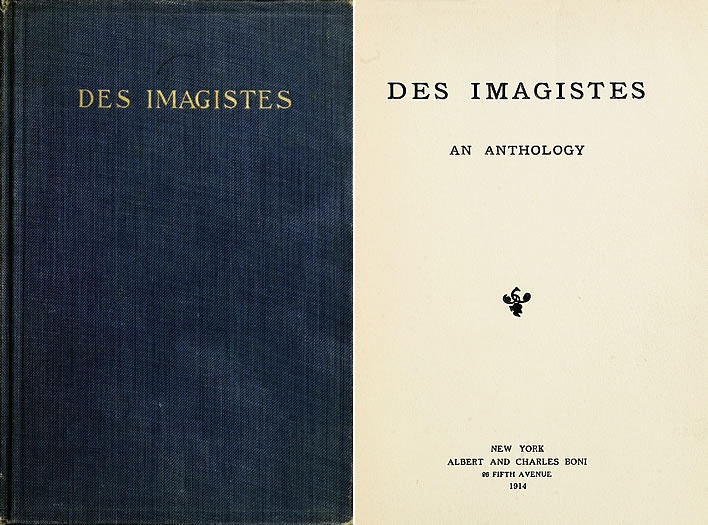

Pay attention now: The anthology was first published in The Glebe, Vol. 1, No. 5, in New York in February 1914, under the title Des Imagistes: An Anthology. Later that year the collection was published as a book by Charles and Albert Boni in New York under the same title.

Image: New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1914.

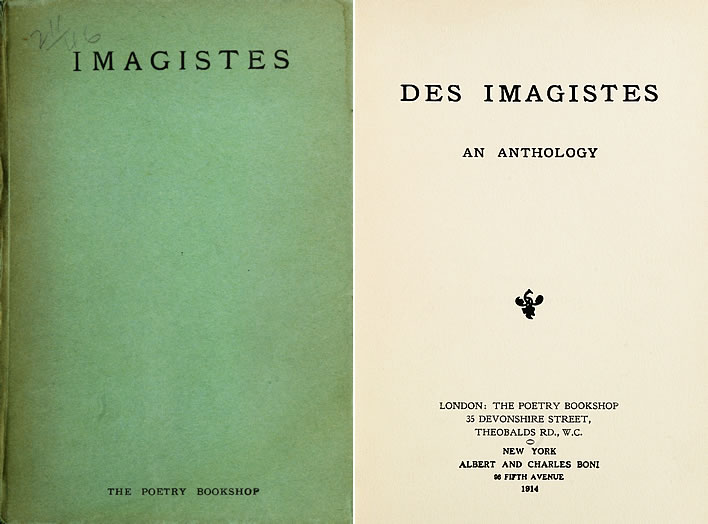

Harold Monro's Poetry Bookshop also sold the volume, which on the (overprinted) title page carried the same title as before, but on the cover the title was simply Imagistes.

Image: London: The Poetry Bookshop, 1914.

This explains why the Poetry Bookshop flyer for the book is titled simply Imagistes, without the Des.

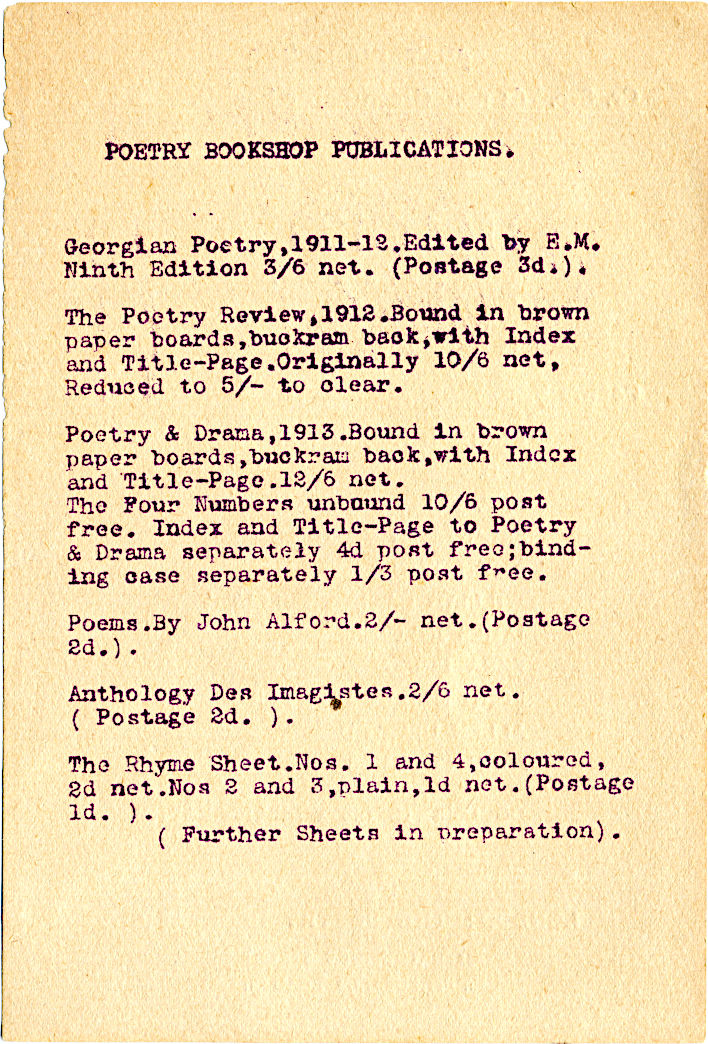

Just to add further confusion the reverse of the leaflet bears a list of Poetry Bookshop publications, printed using a spirit duplicator (it seems). Among this list we also find an entry for Des Imagistes, this time with the full title but presumably meaning the same work.

Image: ©Figures of Speech, reuse only with link to this page.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!