Three early November anniversaries

Richard Law, UTC 2018-11-01 15:28

We may as well get them all over with at once.

5 November 1718: Tristram Shandy born (300 years ago)

Tristram's birth on 5 November completes the process that was started with his disastrous conception. Things can only get worse for him.

On the fifth day of November, 1718, which to the æra fixed on, was as near nine kalendar months as any husband could in reason have expected, —was I Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, brought forth into this scurvy and disastrous world of ours. — I wish I had been born in the Moon, or in any of the planets, (except Jupiter or Saturn, because I never could bear cold weather) for it could not well have fared worse with me in any of them (though I will not answer for Venus) than it has in this vile, dirty planet of ours, — which, o' my conscience, with reverence be it spoken, I take to be made up of the shreds and clippings of the rest; — not but the planet is well enough, provided a man could be born in it to a great title or to a great estate; or could any how contrive to be called up to publick charges, and employments of dignity or power; —but that is not my case; — and therefore every man will speak of the fair as his own market has gone in it; —for which cause I affirm it over again to be one of the vilest worlds that ever was made; — for I can truly say, that from the first hour I drew my breath in it, to this, that I can now scarce draw it at all, for an asthma I got in scating against the wind in Flanders; — I have been the continual sport of what the world calls Fortune; and though I will not wrong her by saying, She has ever made me feel the weight of any great or signal evil; — yet with all the good temper in the world I affirm it of her, that in every stage of my life, and at every turn and corner where she could get fairly at me, the ungracious duchess has pelted me with a set of as pitiful misadventures and cross accidents as ever small Hero sustained.

Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Everyman's Library 1991 / Golden Cockerell 1929, p. 8-9.

Laurence Sterne (1713-1768) published his ground-breaking novel Tristram Shandy in 1759. In this portrait of Sterne by Sir Joshua Reynolds from 1760, Sterne's arm rests upon the manuscript of the novel, which was the talk of London at the time. National Portrait Gallery, London

In 1776, Dr Johnson famously said of the novel: 'Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last.' (James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, I, 1776, p. 27.)

18 November 1808: Lord Byron's dog 'Boatswain' died (210 years ago)

It is fair to say that George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) was a great dog lover, but a terrible dog owner. His dog handling techniques may justly be described as 'Byronic', since the animals seem to have modelled themselves on their master, who was famously described as 'mad, bad and dangerous to know'.

You ask me to recall some anecdotes of the time we spent together at Harrowgate in the summer of 1806, on our return from college, he from Cambridge, and I from Edinburgh; but so many years have elapsed since then that 1 really feel myself as if recalling a distant dream. We, I remember, went in Lord Byron's own carriage, with post-horses; and he sent his groom with two saddle-horses, and a beautifully formed, very ferocious, bull-mastiff, called Nelson, to meet us there. Boatswain went, by the side of his valet Frank, on the box, with us.

The bull-dog, Nelson, always wore a muzzle, and was occasionally sent for into our private room, when the muzzle was taken off, much to my annoyance, and he and his master amused themselves with throwing the room into disorder. There was always a jealous feud between this Nelson and Boatswain; and whenever the latter came into the room while the former was there, they instantly seized each other; and then, Byron, myself, Frank, and all the waiters that could be found, were vigorously engaged in parting them,—which was in general only effected by thrusting poker and tongs into the mouths of each. But, one day, Nelson unfortunately escaped out of the room without his muzzle, and going into the stable-yard fastened upon the throat of a horse, from which he could not be disengaged. The stable-boys ran in alarm to find Frank, who, taking one of his lord's Wogdon's pistols, always kept loaded in his room, shot poor Nelson through the head, to the great regret of Byron.

Thomas Moore, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, vol 1, London, 1830, p. 77.

Asked in 1815 about his memories of the dogs he had owned Byron wrote:

But as for canine recollections, as far as I could judge by a cur of mine own (always bating Boatswain, the dearest and, alas ! the maddest of dogs), I had one (half a wolf by the she side) that doted on me at ten years old, and very nearly ate me at twenty. When I thought he was going to enact Argus, he bit away the backside of my breeches, and never would consent to any kind of recognition, in despite of all kinds of bones which I offered him.

Ibid, p. 602.

Byron's favourite dog was a Newfoundland (therefore, like his master, a good swimmer) he called Boatswain (or Bosun or Bos'n) (1803-1808). He died of rabies.

One glance at Boatswain's collar will indicate the defenses a dog needed to survive in Byron's wild pack. The collar was sold recently: the expected price was between £3,000 and £5,000, the final sale price was £14,000. Image: Tennants / Photographer Harry Middleton.

In the November of this year [1808] he lost his favourite dog, Boatswain, —the poor animal having been seized with a fit of madness, at the commencement of which so little aware was Lord Byron of the nature of the malady, that he, more than once, with his bare hand, wiped away the slaver from the dog's lips during the paroxysms. In a letter to his friend, Mr. Hodgson, he thus announces this event: "Boatswain is dead! —he expired in a state of madness on the 18th, after suffering much, yet retaining all the gentleness of his nature to the last, never attempting to do the least injury to any one near him. I have now lost every thing except old Murray."

Ibid, p. 154.

Byron initially wanted Boatswain to be buried in the grave foreseen for his master, but in the end he received his own fine grave and monument on Newstead Abbey, the family estate:

Boatswain's monument in the grounds of Newstead Abbey. Image: geograph.org.uk / photographer Trevor Rickard.

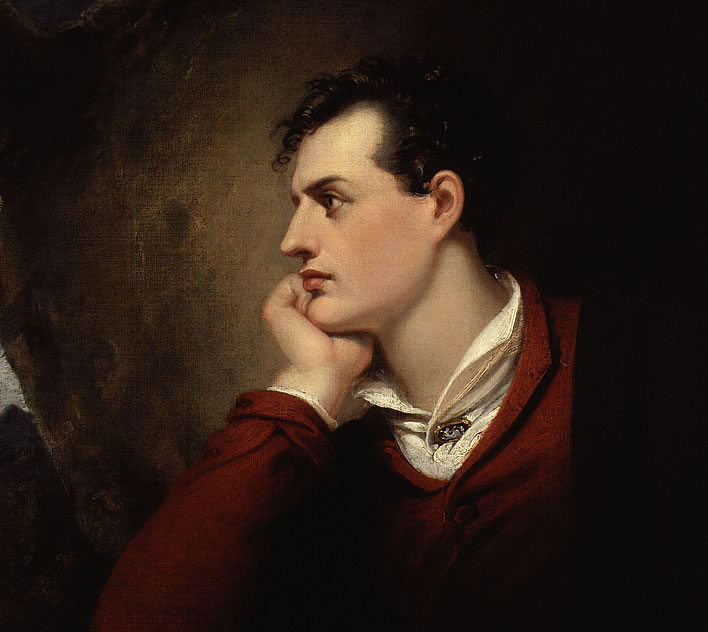

Richard Westall (1765-1836), George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, 1813. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

14? November 1878: Arthur Rimbaud crossed the Gotthard on foot (140 years)

If you know nothing about the French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) you may consider yourself fortunate and should resolve at once never to bother to find out about him. He packed far more into his 37 years on earth than the average person does in 90 – admittedly he started early.

His life was by turns and sometimes all at once madcap, degenerate, wild, dissentient. The only predictable thing about it was that it was completely unpredictable.

For his crossing of the Gotthard we join Arthur in the house of his long-suffering mother in Charleville (now Charleville-Mézières, in north-eastern France). He tells her he is to undertake a business venture that requires him to go to Alexandria. He left home on 20 October 1878, his twenty-fourth birthday, bound for the port of Genoa, from whence he would sail to Egypt. In between Charleville and Genoa stood the Alps and the Gotthard Pass. At the time of Arthur's crossing, the railway tunnel was still being blasted through the rock – it would only be completed in 1884.

We don't know the precise dates of Arthur's Gotthard transit, but he wrote to his mother and sister in a letter dated 17 November 1878 from Genoa, meaning that the crossing must have occurred a few days before. It is illuminating to compare Rimbaud's account of the crossing with the various accounts of Goethe, who traversed the southern side of the Gotthard in one way or another in 1775, 1779 and 1797.

Goethe is very much the Enlightenment observer: observing, recording, speculating on the wonders he encountered; admiring of the Capuchins who run the hospice at the pass summit and the hardships they suffered. Rimbaud, on the other hand, couldn't be more different; utterly contemptuous of these monks – he is a man who hates easily. Well, judge for yourself:

The road, which is never wider than six metres, is filled the whole way with nearly two metres of fallen snow, which, at any moment, might collapse, covering you with a metre-thick blanket you have to hack through during a hailstorm. And then: no more shadows above, below, or beside, despite being surrounded by these massive things; no more road, or precipices, or gorges or sky: just whiteness out of a dream, to touch, to see or not to see, since it's impossible to look away from the white annoyance in the middle of the road. Impossible to lift your head with the biting wind, eyelashes and mustaches becoming stalactites, ears torn, necks swollen. Without the shadow that is oneself, and without the telegraph poles to mark what one must assume remains of the road, you would be as flustered as a sparrow in an oven.

All this, just to get through snow a metre high, a kilometre long. You haven't seen your knees in some time. It's exhausting. Breathless – since in a half-hour the storm can bury you effortlessly – you offer each other shouts of encouragement (you never climb all alone, only in groups). Finally a road-mender appears: you buy a bowl of saltwater for 1.50. And then back at it. But the wind picks up, you see the road begin to fill. Here's a convoy of sleighs, a fallen horse half-buried. The road disappears. Are we on the road or next to it? … You get off course, sink into the snow up to your ribs and then your armpits … A pale shadow behind a clear path: the Gotthard hospice, a civil and medical facility, a hulking mass of pine and stone; a steeple.

When you ring the bell, a seedy-looking young man comes to the door; you take the steps to a dirty, low-ceilinged room where you are given the legally determined minimum of bread and cheese, soup and drink. You see the great big yellow hounds everyone has heard of. Soon, half-dead latecomers come in off the mountain. At night, after soup, the thirty of us spread out on hard mattresses under inadequate covers. At night, we hear our hosts exhaling their holy canticles in praise of another day of theft from the government that subsidizes their little hovel.

In the morning, after a morsel of bread and cheese, steadied by this free hospitality that will last as long as the storm dictates, you leave: this morning, in the sun, the mountain is a marvel: no more wind, all downhill, taking shortcuts, making leaps, tumbling for kilometres …

There's snow on the road for the thirty kilometres from Gotthard. Only after thirty kilometres, at Giornioco, the valley widens a little. A few vine-covered bowers and a few patches of meadow that we light carefully with leaves and other detritus from fir trees that must have served as bedding. Goats move down the roads, gray cows and bulls, black pigs. At Bellinzona, there is a major livestock market. At Lugano, twenty leagues from Gotthard, you get the train and go from pleasant Lake Lugano to pleasant Lake Como. After that, the expected route.

The translation is by Wyatt Mason, I Promise to Be Good: The Letters of Arthur Rimbaud, Modern Library Classics, 2004.

Arthur Rimbaud's trajectory after his departure from Genoa until the end of his life is so complicated and imponderable that we are not even going to attempt a summary here. He died, 37 years old, on 10 November 1891, 127 years ago.

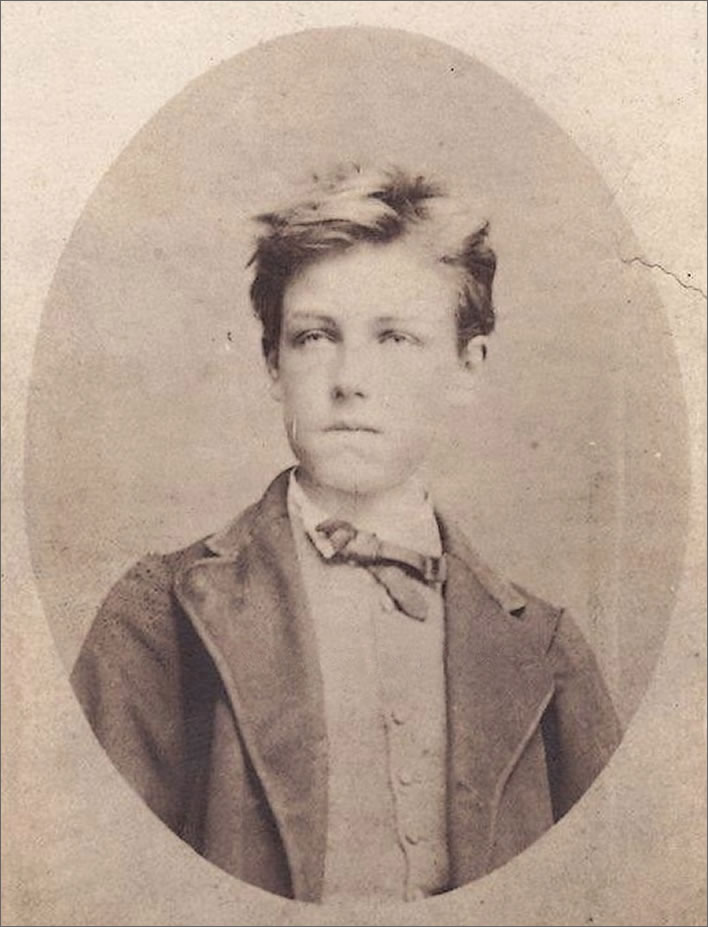

A photographic reproduction (made around 1912) of the original photographic visiting card by Étienne Carjat, from c. 1872. Rimbaud was seventeen at the time. Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!