Friedrich Rückert – Kindertodtenlieder

Posted by Richard on UTC 2019-01-13 10:39 Updated on UTC 2020-07-11

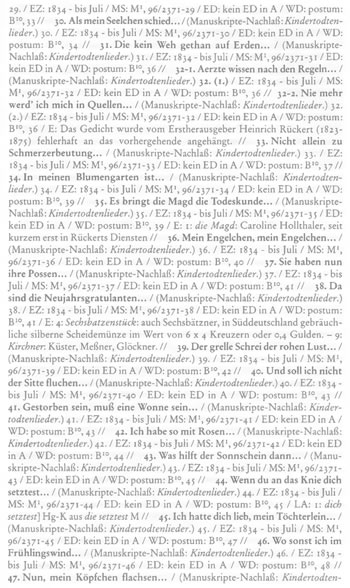

Friedrich Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder is a collection of 563 poems he wrote in the first half of 1834 following the deaths of his two youngest children from scarlet fever. Since its first edition in 1872, the work has been mangled and misunderstood. Many mistakenly assume, for example, that the five poems set to music by Gustav Mahler in 1904 comprise the entire collection. This article is an attempt to restore the reputation of Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder as one of the very greatest products of nineteenth-century German poetry.

The Rückert family

A comprehensive biography of Friedrich Rückert has yet to be written – a sign of the neglect that this important German literary figure suffers to this day. We are not going to attempt one here, either – the briefest sketch will have to do. Here is a summary of the basic biographical facts about the Rückert family that we need to get us to our subject, the Kindertodtenlieder.

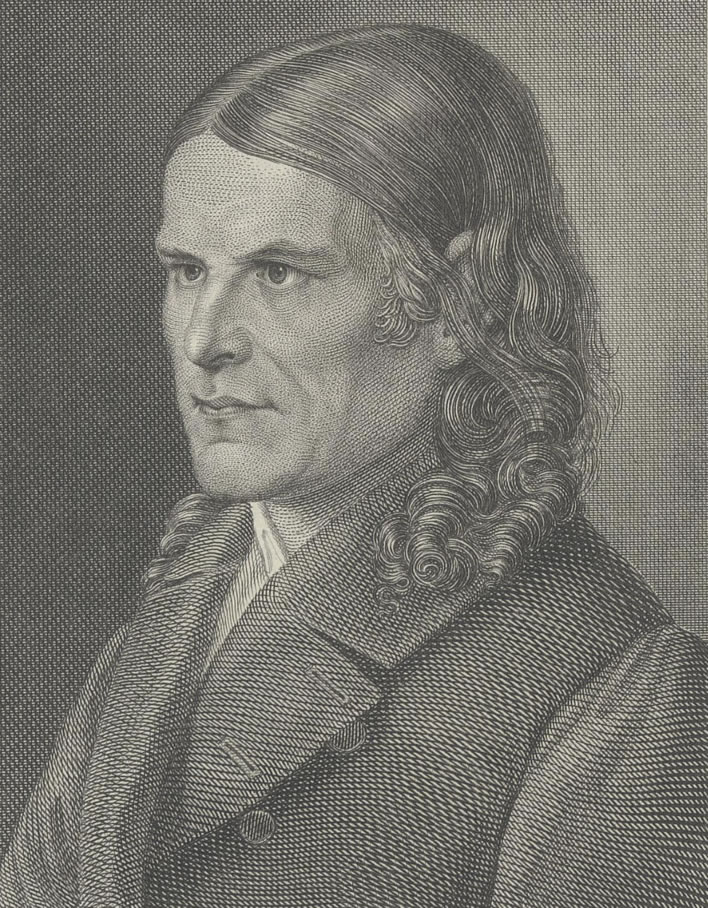

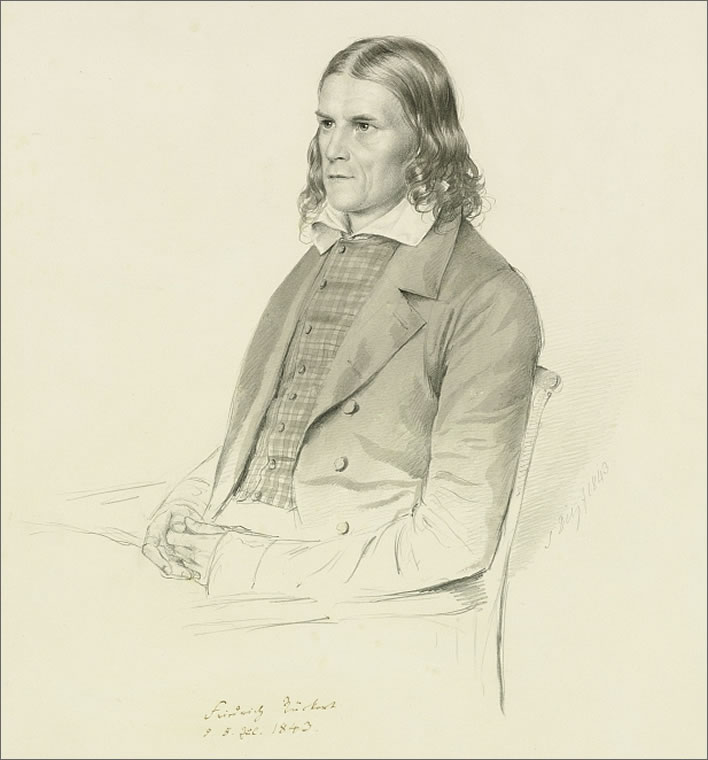

Friedrich Rückert (1826) by Karl Barth (1787–1853). Barth was a great friend of Rückert's, his 'dear friend and engraver', as he addressed him in his letters to Barth. Barth's later years were troubled by mental health problems, particularly the paranoid conviction that he was being pursued by the Jesuits. On 19 August 1853 he threw himself from the top floor of the Gasthaus in Guntershausen (near Kassel) crying: 'They are coming. They are coming'. It was a messy end: it took until 11 September for his wish to be fulfilled. [ADB] Image: Coburg, Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg.

Johann Michael Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) was born on 16 May 1788 in Schweinfurt, now in northern Bavaria. On 26 December 1821 in Coburg he married Luise Wiethhaus-Fischer (1797-1857). Five sons were born in quick succession: Heinrich (1823-1875), Karl (1824-1899), August (1826-1880), Leo (1827-1904) and Ernst (1829-1834). They then had one daughter, Luise Therese Emilie (1830-1833). A sixth son, Karl Julius was born on 6 January 1832, but died three days later.

Luise Rückert as a bride, 1821, by Karl Barth (1787–1853). Image: © Literaturportal Bayern.

At the time the Kindertodtenlieder were written, Friedrich Rückert had made a name for himself as a poet, a patriot and an outstanding orientalist scholar. He was teaching at the University of Erlangen and the family were living in Erlangen (now the Südliche Stadtmauerstraße 28).

Starting at Christmas in 1833, all the children became ill with Scharlach, scarlet fever. The older ones survived but Luise died on 31 December (three and a half years old), Ernst on 16 January 1834 (five years and twelve days old).

For completeness we should mention that, after the disaster of their double loss, the Rückerts went on to produce three more children: Marie (1835-1920), Fritz (1837-1868) and Anna (1839-1919).

A diary of bereavement

Distraught at the loss of his two youngest children, the already productive Rückert, of whom it has been said that he almost 'thought in verse', went into poetic overdrive: in the five or six months immediately following the deaths of Luise and Ernst he wrote 563 poems, an average of approximately three per day.

The creative process behind the Kindertodtenlieder is more that of a diary, journal or – in modern parlance – a live blog than a collection or even a cycle of poems.

Further evidence of Rückert's affinity for this approach is the fact that, starting roughly with his retirement in 1848, his poetic works – thousands of poems – were committed to a Liedertagebuch, a 'Poetic Journal' – a blog in other words. That's how Rückert worked: he was thinking in verse and recording those thoughts on a daily basis.

Rückert's 'bereavement blog' is quite remarkable in many ways. One of them is that it is completely 'raw' – at the end of the composition process around the end of June 1834 the manuscript left Rückert's hands and he never revised a line of it. Given the fluency of this poetry we really can believe that he 'thought in verse'. He decided at some point shortly thereafter that the work as a whole would never be published. We might see this as the equivalent of the modern need to put a bad experience behind you.

One further remarkable feature is that the poetry of the Kindertodtenlieder is quite astonishingly honest and immediate. Whilst displaying immense artistry in his versification, Rückert's day-to-day feelings during that terrible time were not artificially modulated. They are quite direct and the lack of any revision or editing process ensured that they stayed that way. In his openness about his own private feelings and emotions Rückert achieves a universal interpretation of grief and bereavement: the modern reader can relate to Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder without the slightest difficulty.

For reasons we shall discuss later, Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder have been neglected and misunderstood. So, this January 2019, 185 years after the events that led to them, let's take a fresh look at Rückert's great work. Native speakers of German may find some of these poems to be the most wonderful things they have read; English speakers will have to put up with the clunky literalism of our translations and try and remember that they are not reading an instruction manual for a washing machine.

Light and darkness on Christmas Eve

The first hint of the catastrophe that was to befall the Rückerts came on Christmas Eve, 1833.

In Germany at that time, Christmas, quite in keeping with the religious idea at its centre, was a festival for the family and particularly for children. With six children in the house, the Rückerts had their hands full at Christmas.

In the German tradition the exchange of presents took place in the afternoon or evening of Christmas Eve. The Christmas tree was lit with candles and decorated with biscuits and chocolates. Luise had tried 'to fulfil all the [children's] wishes' for presents and particularly 'those of the two youngest', Luise, then three and a half and Ernst, nearly five. [KTL 549]

In the Kindertodtenlieder, Friedrich describes the theatricality of the moment on Christmas Eve when the Christmas tree was revealed and the children received their presents.

| Hier im dunkeln Stübchen Saßen meine Bübchen, Und das Mädchen drunter, Lauschten froh und munter, Harrend ungeduldig, Bis die Mutter huldig Würd' aufthun die Thüren Und hinein sie führen In die hellen Räume Unter Weihnachtsbäume. [KTL 340] |

Here in the darkened room my boys sat and among them sat the girl, listening happily and cheerfully, waiting impatiently until their beloved mother opened the doors and led them into the bright room and underneath the Christmas tree. |

'There was much happiness', Luise noted, 'but not as loud as usual'. But when Christmas Day came, there was nothing left of Christmas happiness:

| Nicht allein zu Schmerzerbeutung Unheilvoller Worte Deutung Sprech' ich, wie ich hörte, nach, Die zum Kind die Mutter sprach: |

Not simply to capture grief in the divination of fateful words, I repeat, as I heard them, the words the child spoke to her mother: |

| Was zu naschen, was zu spielen Von so schönen Sachen vielen Magst du Kind? Das Kind sprach schwer: Mutter, ich mag gar nichts mehr. [KTL 52] |

Would you, my child, like something to nibble at, something to play with, something from these beautiful things? The child spoke wearily: Mother, I don't want anything more at all. |

That the miserable illness of scarlet fever blighted all six children just at the time of the Christmas celebration of the family was a dismal irony.

After the first intimations of the onset of the disease on Christmas Eve, by Boxing Day there was no longer any doubt that illness had struck them. The youngest, Luise, the only daughter among five boys, was the first to succumb. The doctor was called that evening to her.

Luise, the special one

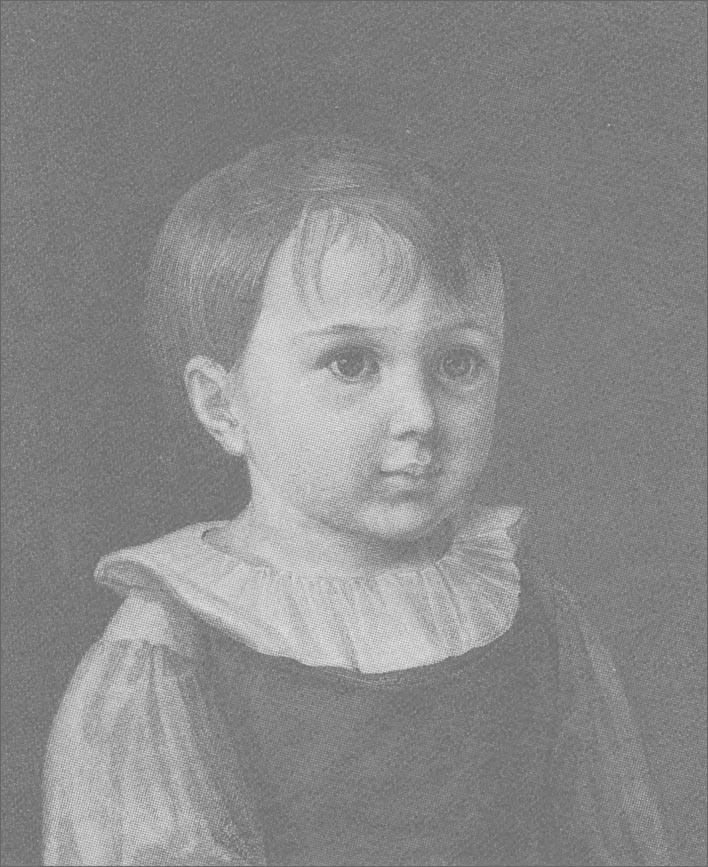

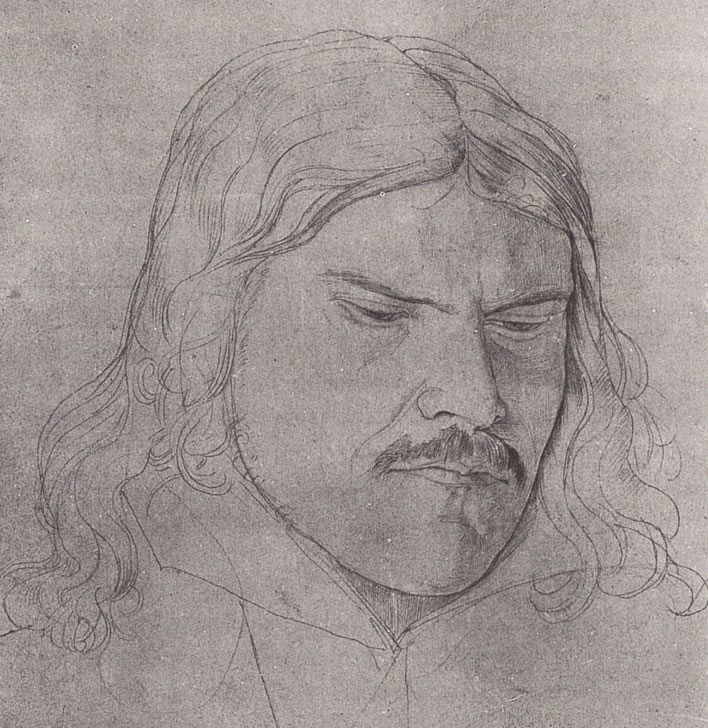

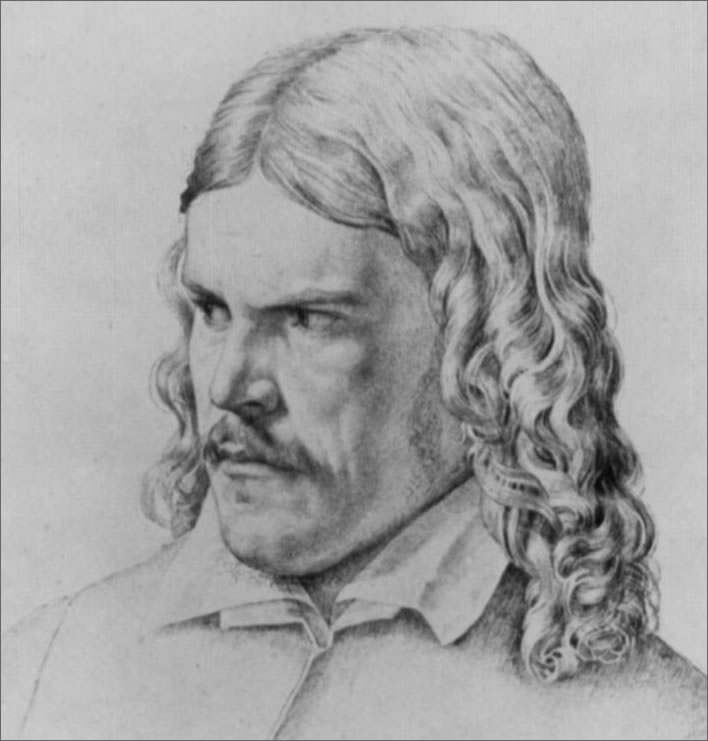

Luise Therese Emilie Rückert (1830-1833). Both this portrait and that of Ernst (below) were done by Rückert's friend Karl Barth initially in the autumn of 1833. A short time later both of the children were dead and Barth's pictures took on a deep emotional significance for the Rückerts. In the course of 1834 Barth produced an improved copy of each picture. The pictures were placed in gilded frames. In Erlangen they hung over Rückert's desk and travelled with him on all his subsequent removals. Visitors to Rückert's house in Coburg-Neuses (the Nattermannshof) will see them there today.

As the youngest sibling and the only daughter, Luise had a special place in her father's heart. Friedrich Rückert grew up with four sisters: Sabine Sophie, one year older, (1791-1848) and three short-lived younger sisters Anna Magdalena (1793-1795), Ernestine Helene (1795-97) and Susanna Barbara (1797-1801). The family lived in a house in Oberlauringen, a small town about 20 km from Schweinfurt.

| Als Knabe war mein größtes Wohlbehagen, Ein Schwesterchen im Arm zu tragen, Geflüchtet aus der engen Stub' hinaus, Im weiten Garten hinter'm Haus. |

As a boy my greatest pleasure was to carry a little sister in my arms, fleeing out of the cramped room into the large garden behind the house. |

| Doch hatte bald der Tod mein Wohlbehagen Mir aus dem Arm zu Grab getragen, Und in des Lebens Braus vergaß der Knab Das Schwesterchen im stillen Grab. … |

But death soon carried my pleasure from my arms to the grave and in a hectic life the boy forgot that little sister in the quiet grave. |

| Inzwischen hatt' ich, größres Wohlbehagen, Ein Töchterchen im Arm zu tragen, Das, kommend still nach lauter Buben Troß, Mein halbes Dutzend lieblich schloß. [KTL 68f] |

But now I had the greater pleasure of carrying a little daughter in my arms, who, arriving quietly after a noisy crowd of boys, beautifully concluded my half dozen. |

German speakers will enjoy the characteristically Rückert-style structural formalities of this poem. The Lebens Braus, 'life's turmoil' refers to the period from 1802, when Rückert ended his time at the village school in Oberlauringen and went to the Gymnasium Gustavianum in Schweinfurt, where he spent three successful years. The sister he carried out into the garden was Susanna Barbara (1797-1801).

In Rückert's own family, little Luise was taken under the wings of her older brothers, just as her father had taken his little sisters under his wings. We can imagine that, having experienced as a child the loss of his own infant sisters, the loss of yet another infant girl would be an especially hard blow for Friedrich:

| Von den Brüdern jedem war ein Lieblingsschwesterchen geboren, Der Mutter ein Lieblingstöchterchen, Und mir selber eines. |

For each one of the brothers a favourite little sister had been born, for the mother a favourite little daughter, and one for me, too. |

| Von den Brüdern jeder hatt' ein Lieblingsschwesterchen erkoren, Die Mutter ein Lieblingstöchterchen, Und ich selber eines. |

Each one of the brothers had chosen a favourite little sister, the mother a favourite little daughter, and I, too. |

| Von den Brüdern jeder hat sein Lieblingsschwesterchen verloren, Die Mutter ihr Lieblingstöchterchen, Und ich selber meines. [KTL 70] |

Each one of the brothers lost a favourite little sister, the mother a favourite little daughter, and I, mine. |

The same German speakers who enjoyed the poetic playfulness in the previous poem will here have encountered a fascinating augmentation of Rückert's structural skills. The polyglot Rückert's brain seems to have been hard-wired to play games with language that would cost us plodders a week of pencil chewing to achieve – if we ever could.

The five boys took brotherly care of this small doll in their midst. In the light of Rückert's anecdote of his own attachment to his little sister, Susanna Barbara, there can be no doubt that the chivalry of his own sons to their little sister made Rückert very happy and proud. Luise herself seems to have coped with all these brothers intuitively well:

| Von fünf Brüdern, o beneidenswerthe Schwester, wärest du umworben; Jeder zu gefallen dir begehrte, Gern für dich entbehrte, Wäre gern für dich gestorben. |

From five brothers you were courted, O enviable sister; each one seeking your favour, happy to do without for you, would have happily died for you. |

| Keinem wolltest du den Vorzug geben, Jeder Dienst war dir willkommen; Doch zuletzt nun hast du beim Entschweben Deinen jüngsten eben Als den liebsten mitgenommen. [KTL 103] |

You gave your preference to no one, every deed was welcome; in the end, however, at your departure, you took the youngest brother as your preferred one with you. |

In Luise's case, the scarlet fever took a hold on her that could not be released. Her condition became worse with each day. Soon it became obvious that her death was approaching. Rückert pleaded for her to live just one more day, even in her suffering:

| Du hast uns überlebt die Nacht, Wiewohl in Todesschmerzen; Und auch dafür sei dargebracht Ein Dank von unsern Herzen; Wenn uns auch nur noch einen Tag Dein süßes Leben bliebe; |

You have survived the night for us, though in mortal agony; and thanks for that are offered from our hearts; if only just one day more of your sweet life remained; |

| So lang als möglich halten mag Ja, was sie liebt, die Liebe. Auf lange fest ja halten mag Nichts, was sie liebt, die Liebe; Genug, daß nur von Tag zu Tag Sich der Verlust verschiebe. [KTL 120] |

love may hold that which it loves as long as possible. In time though love can hold nothing which it loves; sufficient that the loss is postponed from day to day. |

Her dying, even though expected, was a shock for which no parent could prepare. As her breathing became more and more difficult she was overcome by mortal fear and her final agony began. She died at two-thirty in the morning on 31 December, less than six days after the first major symptoms had appeared on Christmas Day. Her mother, father and the five brothers were stunned:

| Es bringt die Magd die Todeskunde Vom Schwesterchen der Knabenschaar; Da rufen sie mit Einem Munde: Sie ist nicht todt, es ist nicht wahr. |

The maid brings the news of the death of their sister to the crowd of boys; they shout with one voice: she is not dead, it is not true. |

| Sie sehen sie mit blassem Munde Mit weißer Wang' im dunklen Haar, Und flüstern leiser in die Runde: Sie ist nicht todt, es ist nicht wahr. |

They look at her with pale mouth, with white cheek in dark hair, and whisper quietly to each other: she is not dead, it is not true. |

| Der Vater weint aus Herzenswunde, Die Mutter weint, sie nehmens wahr, Und bleiben doch bei ihrem Grunde: Sie ist nicht todt, es ist nicht wahr. |

Her father weeps from the wound in his heart, her mother weeps, they see it, yet remain convinced: she is not dead, it is not true. |

| Und als gekommen war die Stunde, Man legt sie auf die Todtenbahr, Man senkt sie ein im kühlen Grunde: Sie ist nicht todt, es ist nicht wahr. |

And when the moment came when she was laid on the bier and lowered into the cool earth: she is not dead, it is not true. |

| So bleibe sie mit euch im Bunde Und werde schöner jedes Jahr, Und werd' euch lieber jede Stunde! Sie ist nicht todt, es ist nicht wahr. [KTL 54] |

So she will stay united with you and become more beautiful every year and be more loved by you with every hour! She is not dead, it is not true. |

Luise was buried at nine o'clock on 3 January, in her favourite white dress. A myrtle garland was put on her forehead and numerous flowers laid on her body. Her mother adds: 'Two wonderful red hyacinths, which the children and I had planted with great pleasure had just come into bloom. I placed them on her breast and she lay there as though the bride of an angel.' [KTL 552]

Rückert summarised bitterly that terrible festive season in his household using the calendar of religious feast days:

| Weihnachten frisch und gesund Im frohen Geschwisterrund, Am Neujahr mit blassem Mund, An den drei Kön'gen im Grund. So thaten die Feste sich kund Mit Tod und Grab im Bund. Mein Herz bleibt bis Ostern wund Und wird nicht bis Pfingsten gesund. [KTL 82] |

Christmas fresh and healthy in the happy circle of siblings, New Year with pale mouth, Epiphany in the earth. That's how the feast days made themselves known, in union with death and the grave. The wound in my heart remained until Easter and will not be healed by Whitsun. |

Last things: guilt and regret

Her death released a wave of grief and guilt out of which Rückert's poetic mind created some of his greatest and most moving poems.

| Ich hatte dich lieb, mein Töchterlein! Und nun ich dich habe begraben, Mach' ich mir Vorwürf', ich hätte fein Noch lieber dich können haben. |

I loved you my daughter! And now I have buried you I reproach myself that I could have been more loving to you. |

| Ich habe dich lieber, viel lieber gehabt, Als ich dirs mochte zeigen; Zu selten mit Liebeszeichen begabt Hat dich mein ernstes Schweigen. |

I loved you much more than I wanted to show you; you received too rarely the signs of love, only my stern silence. |

| Ich habe dich lieb gehabt, so lieb, Auch wenn ich dich streng gescholten; Was ich von Liebe dir schuldig blieb, Sei zwiefach dir jetzt vergolten! |

I loved you, so much, even when I scolded you severely; let what love I owed you be repaid twice over! |

| Zuoft verbarg sich hinter der Zucht Die Vaterlieb' im Gemüthe; Ich hatte schon im Auge die Frucht, Anstatt mich zu freun an der Blüte. |

Too often the feeling of fatherly love was hidden behind the discipline; I was already thinking of the fruit, instead of enjoying the blossom. |

| O hätt' ich gewußt, wie bald der Wind Die Blüt' entblättern sollte! Thun hätt' ich sollen meinem Kind, Was alles sein Herzchen wollte. |

Oh, if only I had known how quickly the wind would strip the petals from the blossom! I would have done everything for my child that her heart had desired. |

| Da solltest du, was ich wollte, thun, Und thatst es auf meine Winke. Du trankst das Bittre, wie reut michs nun, Weil ich dir sagte: Trinke! |

You had to do what I wanted and do it at my bidding. You drank the bitter potions, how I regret it now, just because I told you: Drink! |

| Dein Mund, geschlossen von Todeskrampf, Hat meinem Gebot sich erschlossen; Ach! nur zu verlängern den Todeskampf, Hat man dirs eingegossen. |

Your mouth, clamped in the cramp of death had followed my command; Oh! just to extend the death agony it had been poured into you. |

| Du aber hast, vom Tod umstrickt, Noch deinem Vater geschmeichelt, Mit brechenden Augen ihn angeblickt, Mit sterbenden Händchen gestreichelt. |

You, however, tangled up in death, looked at your father with tear-filled eyes and caressed him with a dying hand. |

| Was hat mir gesagt die streichelnde Hand, Da schon die Rede dir fehlte? Daß du verziehest den Unverstand, Der dich gutmeinend quälte. |

What did the caressing hand say to me, since speech could no longer come? That you forgave the well-intentioned ignorance which tormented you. |

| Nun bitt' ich dir ab jedes harte Wort, Die Worte, die dich bedräuten, Du wirst sie haben vergessen dort, Oder weißt sie zu deuten. [KTL 64f] |

Now I ask you to forgive each hard word that oppressed you, you will forget them there, or know how to interpret them. |

Hindsight modulated through grief led to immense regret, not just for what he now held to be the commission of misguided actions but for the omissions which he could now never make good.

Some of the poems in the Kindertodtenlieder are written from the viewpoint of the mother. They were not written by her, however. Although we know next to nothing about the process of the creation of the poems in the collection, it is easy to imagine that the mother's utterances to her husband on her loss could well form the material out of which Rückert forged some of his poems:

| Ich hab' in läss'gen Ohren, O der Verlust ist groß, Wol manches Wort verloren, Das dir vom Munde floß. |

I have in casual ears – Oh the loss is great – lost some of the words that flowed from your mouth. |

| Es floß und quoll und rollte Auch immer klar und hell, Ich dachte nicht, es sollte Versiegen je der Quell. |

It always flowed and gushed and rolled clear and light. I never thought the spring would ever dry up. |

| Da hört' ich ohne Hören, Antwortet' ohne Wort, Arbeitet' ohne Stören, Und du sprachst immer fort. |

I heard without listening, answered without words, worked on without disturbance and you spoke on and on. |

| Nur manchmal hört' ich sagen, Wenn ichs zu arg gemacht: O Mutter, auf mein Fragen Gibst du auch gar nicht Acht. |

Only sometimes I heard it said, if I took it too far: Oh mother, you don't pay any attention to my questions either. |

| Und hatt' ich Acht zu geben Auf andres als auf dich? Mein süßgeschwätz'ges Leben, Nun bist du stumm für mich. |

And did I have to pay attention to others rather than you? My sweetly chattering life, now you are silent for me. |

| In Gold nun möcht' ich fassen Auch jedes kleinste Wort, Das mir dein Mund gelassen In der Erinnrung Hort. [KTL 96] |

Now every little word which left your mouth I would like to embed in gold in my memory. |

Guilt, regret but especially loss, the latter manifested in memories that seem to arise from a now distant world:

| Es war kein Traum, Ich muß mirs immer wieder sagen, Und glaub' es kaum, So traumhaft hat es sich zerschlagen. |

It was no dream, I have to keep telling myself and hardly believe it, so dream-like was it dashed. |

| Es war kein Traum, Ich hab' in schönem Sommertagen In diesem Raum Die Ros' an meiner Brust getragen. [KTL 400] |

It was no dream, in summer days in this room I carried the rose [Luise] on my chest. |

The order of things

Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder are not merely lamentations of loss. In effect he was writing a poetic diary with three poems a day on average, each of which reflected some momentary meditation on his loss, some of which were thoughtful pieces on the wider implications of a child's death. We have no right to expect measured consistency between these moments.

In the following poem, for example, there are thoughts on the father-daughter relationship as it would have developed had Luise lived.

| Hoffte, daß du solltest bei mir bleiben, Nie verlassen, Töchterchen, den Vater, Wenn die Knaben aus dem Hause liefen, In der Welt ihr eignes Glück zu suchen, Losgerissen von der Eltern Herzen; |

I hoped that you might stay with me and never leave, daughter, your father, when the boys left the house to find their own way in the world, torn free of their parents' hearts. |

| Würdest du am stillen Herde walten, Wo du spielend jetzt dich um die Mutter Mühst, in ihre Stell' im Ernste treten, Wohlversüßt den Kaffee selbst mir bringen, Wie sie jetzt ihn bringt, von dir begleitet. |

You would reign over the quiet hearth, where you now play alongside your mother, striving to take over her place, bring me my perfectly sweetened coffee yourself, just as she brings it now with you at her side. |

| Und nun bringst du diesen bittern Trank mir! Ihn mir zu versüßen, muß ich sagen: Ewig konntest du mir doch nicht bleiben; Unversehens klopfet an ein Freyer, Und entgegen klopfet ihm dein Herzchen, Und: herein! werd' ich wohl sagen müssen. |

And now you bring me this bitter drink! In order to sweeten it I have to say that you could never have remained with me; sooner or later a suitor would knock and your heart would beat at him, and: come in! I would just have to say. |

| Und die junge Gattin wird den Gatten Lieber haben als den alten Vater, Und die Kinder lieber dann als beide. Denn daß über alles man ein Kind liebt, Lern' ich eben, da ich dich verloren. |

And the young wife will love the husband more than the old father, and love her children more than either of them. That one loves a child more than anything else I have just learned, since I lost you. |

| Nun ersparst du diese Eifersucht mir, Töchterchen, nun kannst du deinen Vater Einzig lieb, wie er dich selbst, behalten. [KTL 206] |

Now you have spared me this jealousy, my daughter, now you can love your father alone just as he loves you. |

Rückert's grief is not selfish. His wife was deeply affected and collapsed after the death of little Luise. She took to her bed for some time afterwards.

The following poem opens with a charming, though now in grief painful anecdote, which is developed into a pointed conclusion concerning his wife's importance to little Luise.

| Reizender als alle Sprachen, Die ich jemals lernt' und sprach, Tönt, was deine Lippchen brachen, Mir noch jetzt im Traume nach. |

More delightful than any language which I have learned and spoken, the sounds that came from your lips echo in my dreams. |

| Wenn man dir von Großpapachen Und von Großmamachen sprach, Bildeten in deinen Sprachen Neue Formen kühn sich nach: |

When we spoke to you of 'Great-Father' and 'Great-Mother' you created audaciously new forms in your language: |

| Kleinpapachen, Kleinmamachen, Vater, Mutter, nanntest du, Wenn sie für dich Blumen brachen, Oder trugen Früchte zu. |

'Little-Father', 'Little-Mother' you called your father and mother, when they brought you flowers or fruit. |

| Kleinpapachen! Kleinpapachen! Riefst du recht als wie zur Schmach, Wann dich deine Kitzel stachen, Deinem großen Vater nach. |

'Little-Father'! 'Little-Father'! you shouted mockingly at your big father when your tickles hit home. |

| Kleinmamachen aber sprachen Nicht die Lippchen halb so gern, Weil die Kleinheit von Mamachen Wirklich stand nicht halb so fern. [KTL 80] |

Your lips said 'Little-Mother' not as readily, because the smallness of your mother in reality was not half as distant. |

The joke in the fourth stanza needs some explanation. Friedrich Rückert was a tall man in an age of small men, over two metres (six foot six) tall, so Luise's term for him, 'Little Father', was in that context quite ironic, particularly when the little doll of a child was shouting it while tickling her giant of a father.

Ernst: hanging on to the very bitter end

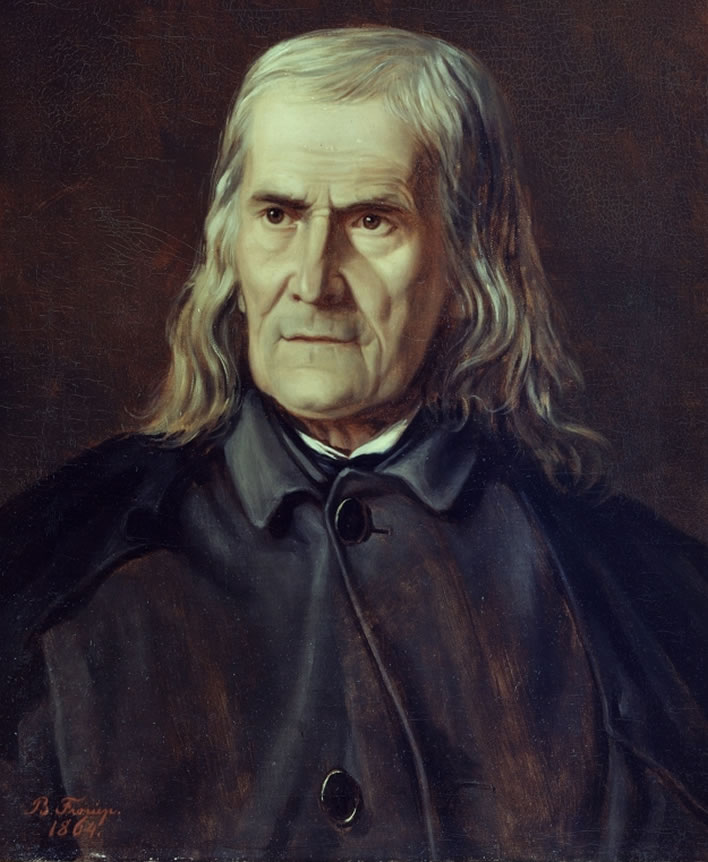

Ernst Rückert (1829-1834) by Karl Barth.

On 1 January 1834, the day after little Luise had died, her brother Ernst took to his bed.

Ernst's suffering would last fourteen days. During that time there were even occasions when he was thought to have died, but then suddenly recovered. For Rückert, losing his beloved daughter Luise had been torture enough, but the dying of his youngest son was a torture magnified and extended.

Ernst hung on, moving in and out of life. The resulting delay merely offered his doctors more time to torment him with their cures – even though they had for some time considered him to be a hopeless case. He had been bled three times on his arms. The wounds from that now began to ulcerate. Like Luise, blistering plasters had been applied to his neck and the itching of the resulting blisters now tormented him: the blisters were scratched, wept and bled. Cold flannels were applied that made him shiver until his teeth literally chattered.

As a final medical insult, mercury ointment was rubbed onto his head, which he disliked greatly, but, his mother tells us, 'he was obedient to the voices of his father and me until his death, and let it happen.' [KTL 555]

Rückert, who during his daughter's death throes had wished for just one more day of life for her, was so affected by Ernst's sufferings that he now prayed for a rapid end to his son's misery:

| Geh! du kannst ja doch nicht bleiben; Warum willst du gleich nicht gehn? Warum willst du länger leiden, Ringen noch mit Todeswehn? Geh, der Schwester nachzueilen, Laß sie so allein nicht gehn! … |

Go! you cannot stay; why won't you just go? Why do want to suffer longer, wrestle with death agony? Go, hurry after your sister, don't let her go on alone! |

| Und es wird uns Trost ertheilen, Wenn wir auf den Kirchhof gehn, Ja es wird das Herz uns heilen, Wenn bei Frühlingslüfte-Wehn, Eingefaßt von Blumenzeilen Wir dort eure Gräber sehn So vereint, wie eure beiden Bettchen in der Kammer stehn: Auch der Tod kann euch nicht scheiden, Ihr zwei unzertrennlichen! [KTL 135] |

And it will be a comfort for us when we go to the churchyard, yes, it will heal our hearts when in spring breezes, enclosed in rows of flowers we can see your graves side-by-side just like your beds in the bedroom: Even death cannot separate you, you two inseparables! |

Ernst and Luise

After Luise's death, Rückert had written of his difficulty in believing that she had really gone. Now, with Ernst dead, he had two losses to deny. He did so in a very characteristic piece of Rückert versification:

| Wie ich reiflich Wog mein Leid, Es ist doch mir unbegreiflich, Daß ihr mir verloren seid. |

As I carefully weighed my poem, it is incomprehensible that you are lost to me. |

| Sah ich nicht die Todtenbahre, Und den dunkeln Kranz im Haare Meinem schönen Kinderpaare? Doch bezweifl' ich Noch mein Leid, Es ist doch mir unbegreiflich, Daß ihr mir verloren seid. |

Did I not see the bier and the dark wreath in the hair of my beautiful pair of children? Nevertheless I still doubt my poem, it is incomprehensible that you are lost to me. |

| Leugn' ich ab das Offenbare, Und es sei nicht wahr das Wahre! Doch an meinem Hals das klare Fehlt handgreiflich, Das Geschmeid; Und das Weh ist unabstreiflich, Daß ihr mir verloren seid. |

Deny what is manifest and that truth is no longer true! But on my throat the clear evidence is missing, the necklace; and the pain cannot be cast off, that you are lost to me. |

| Kommen nun und gehen Jahre, Und Natur am Brautaltare Bald und bald auch an der Bahre Wechsl' umschweiflich Kleid um Kleid! Diese Schart' ist unauschleiflich, Daß ihr mir verloren seid. [KTL 434] |

Years now come and go, Nature soon at the wedding altar and soon at the bier changes without delay one dress for another! This notch cannot be ground out, that you are lost to me. |

This poem illustrates one of the problems of Rückert's poetry and of the Kindertodtenlieder in particular: conspicuous artifice sometimes distracts from their content. The too-clever-by-half versification suggests only emotional insincerity or superficiality.

In this particular poem, Rückert is seeing how many words of the form —flich he can stack up in the poem. The words become odder and odder – reiflich / unbegreiflich / bezweifl' ich / unbegreiflich / handgreiflich / unabstreiflich / umschweiflich / unauschleiflich – and culminate in the absurd word unauschleiflich [a notch in metal that is] 'incapable of being ground out'.

Rückert was clearly not insincere about the death of his children, but occasionally the crossword-puzzler and word-trickster in him cannot be suppressed. It may very well be, though, that Rückert's self-inflicted confrontation with versification trickery was part of the therapy for him. It was, after all, his métier and took his mind off things.

We should also remember that Rückert never went back and edited the Kindertotenlieder, so that in this poem we confront the raw skill of Rückert's language talent without editorial mediation.

The inseparables

The bereaved person takes comfort wherever it is to be found. Rückert took cold comfort that both Luise and Ernst had died, almost as a pair. In the poem above, Geh! du kannst ja doch nicht bleiben he addressed them finally as Ihr zwei unzertrennlichen!, 'you two inseparables!' They were a pair in death just as they had been in life.

Rückert developed the theme in a poem titled [Die] Inseparables, a German word derived from French, Italian and Latin used at the time for lovebirds, the small African parrots.

INSEPARABLES.

Unzertrennliches, ach vom Tod getrenntes,

Zartverschwistertes, durch Geburt und Neigung,

Für einander geschaffnes Vogelpärchen!

O du Brüderchen, an der Schwester hangend,

O du Schwesterchen, nicht vom Bruder lassend!

In dem sonnigen Käfich, eurem Stübchen,

Auf dem Stängelchen, eurem Stuhle, sitzend,

Immer nebeneinander, aneinander.

Saß das Brüderchen auf der rechten Seite,

Und das Schwesterchen links, so ließ sein Köpfchen

Links das Brüderchen hangen, und sein Köpfchen

Rechts das Schwesterchen, also daß die beiden

Köpfchen leise sich ohne Druck berührten.

Inseparables, ah, separated by death, tender siblings, through birth and inclination, a pair of birds made for each other! Oh you, brother, clinging to the sister, Oh you, sister, not leaving his side! In the sunny cage of your room, sitting on the perches, your chairs, always together, side-by-side. If the brother sat on the right-hand side and the sister the left, the brother tilted his head to the left and the sister tilted her head to the right until the two heads lightly touched each other.

Saß das Brüderchen aber auf der linken,

Und das Schwesterchen auf der rechten Seite,

Denn sie pflegten in diesem Stück zu wechseln,

War das Hängen der Köpfchen auch gewechselt,

Daß sie gegeneinander wieder neigten.

So war euere Neigung gegenseitig,

So war euere Liebe wechselwirkend,

Ohne Wechsel als den der äußern Stellung.

If, however, the brother sat on the left-hand side and the sister on the right, for they used to change like this, then the tilt of the heads also changed, so that they inclined to each other again. So your inclination was mutual, so your love reciprocal, without change other than the external position.

Was ihr aßet, das aßet ihr zusammen,

Und ihr tränket zusammen, was ihr tränket;

Was ihr spieltet und scherztet, sangt und spränget,

Was ihr lebtet, das lebtet ihr zusammen.

Und so seid ihr zusammen auch gestorben.

Als das Schwesterchen mit zerdrückter Brust lag,

Eingedrückt von des Geiers ehrnen Krallen,

Jenes Geiers, vor dem den Lebensvogel

Kein Goldkäfich der Liebe kann beschützen;

Whatever you ate, you ate together, and you drank together whatever you drank; what you played and joked at, sang and jumped, what you lived, you lived together. And so you died together. When the sister lay with a crushed breast, squashed by the vulture's iron claws, that vulture from which no gilded cage of love can protect the bird;

Ließ das Brüderchen auch das Köpfchen hangen,

Nicht zur linken und nicht zur rechten Seite,

Sondern grad' auf die Brust, und hobs nicht wieder.

Und nun laßt uns zusammen sie begraben,

Unter Thränen, am Fuß des Lebensbaumes,

Wo wir klagen um sie im dunkeln Schatten.

[KTL 204f]

the brother also hung his head, not to the left and not to the right side, but rather down on his chest, never to raise it again. And now let us bury them together, under tears, at the foot of the tree of life where we lament them in dark shadows.

The theme of the companionship in death as in life of Luise and Ernst, the two 'lovebirds', is one that inspired Rückert to a number of poems in the Kindertodtenlieder:

| Ach von meinem lieben Schwärmchen Die zwei kleinsten, die zwei feinsten, Immer unter sich am einsten, Die sich hatten lieb am reinsten, Wie sie mit geschlungnen Aermchen Eines um des andern Näckchen, Eines an des andern Bäckchen, Saßen zwei auf einem Stühlchen, Lehnten zwei an einem Pfühlchen, Spielten zwei auf einem Tischchen; … [KTL 129] |

Oh, from my beautiful little swarm the two smallest, the two most delicate, the two most united between themselves, who loved each other the purest, how they sat with their arms wrapped around each other, one around the other's neck, one around the other's cheek, the two sat on one chair, laid back on one couch, played at one table … |

Ernst and Luise were so inseparable that they were given the nickname in the family of 'knife' and 'fork', because they always belonged together and remained next to each other. From its content, the following seems to have been written after Luise's death and during Ernst's illness.

| Zwar ihr beiden ungetrennet, Oft von uns im Scherz genennet Messerchen und Gäbelchen; Weg mit diesem Fäbelchen! Wird uns auch kein Bissen schmecken, Wenn wir unsern Tisch nun decken, Und das Gäbelchen gebricht, Messerchen, nur fehle nicht! [KTL 52] |

But you two unseparated, we often called you jokingly knife and fork; Away with this tale! It will not taste the least bit good when we lay our table now and the little fork broken – little knife, just don't be absent! |

The loss of Ernst may appear not to play as big a role in the Kindertodtenlieder as that of little Luise, but that is partly due to the role of the little sister in Rückert's upbringing and partly to the great shock of the first childhood death. Most importantly, after the death of Luise, Ernst is now frequently mourned as one of a pair, not individually.

Medical torture

It was bad enough for parents to have to watch their children suffering, but having to watch the suffering caused by medical treatments intended to cure them was a terrible ordeal. There was a joke that lasted for centuries, that the sick needed to be really healthy before they called a doctor.

Friedrich Rückert was appalled at the medical torture he had to witness with both Luise and Ernst, treatments that resulted in nothing but more suffering:

| Schlimmer als ein Kranker seyn, Ist es einen haben, Dem man heilend anthut Pein, Quält ihn statt zu laben, Sieht vergehn wie hohlen Schein Jugendhimmelsgaben, Und ist froh nur das Gebein Endlich zu begraben. So mit meinem Mägdelein War es, und nun soll es seyn So mit meinem Knaben. [KTL 105] |

Worse than being ill yourself is looking after an ill person, having to inflict suffering in the cause of healing, having to torment them instead of soothe them, having to watch youthful gifts of heaven disappear like empty show, having to be happy in the end just to bury the bones. That's how it was with my little girl and how it will now be with my little boy. |

In her mother's account we learn that Luise resisted at first, clenching her teeth, so that her parents had to force her mouth open to administer the bitter medicine and to spray it into her throat. Blistering plasters (containing irritants such as cantharidin or mustard powder) were applied around her neck. All, of course, to no avail – mere torture of a dying child. [KTL 551]

Ultimately it was the Rückerts, not the doctors, who had to force their children to drink the useless, bitter potions:

| Da solltest du, was ich wollte, thun, Und thatst es auf meine Winke. Du trankst das Bittre, wie reut michs nun, Weil ich dir sagte: Trinke! [KTL 64] |

You had to do what I wanted and do it at my bidding. You drank the bitter potions, how I regret it now, just because I told you: Drink! |

Rückert had to stand by and watch leeches suck his children's blood, a sight that haunted him:

| (1) Aerzte wissen nach den Regeln Aus der Welt kein Kind zu schaffen, Ohne mit abscheul'chen Egeln Die Naturkraft hinzuraffen. |

Doctors know as a rule no way of removing a child from the world without using revolting leeches to dissipate their natural powers. |

| (2) Nie mehr werd' ich mich in Quellen Unbefangen spiegeln; Immer werd' ich in den Wellen Schaudern vor Blutigeln, |

Never again will I unguardedly look at my reflection in the water of the spring; I shall always now shudder at the thought of leeches. |

| Die das Leben mit dem Blute Meines Kinds entsogen; So mißhandelt ist das gute Seelchen, ach, entflogen. |

Those things which sucked the life out of my child with her blood; thus maltreated, that good soul has, oh!, flown away. |

| Aber nicht aus reinen Quellen, Sondern styg'schem Sumpfe Holt man diese Blutgesellen Zu des Tods Triumphe. [KTL 51] |

But these blood brothers are not collected from clear springs but Stygian marshes, for the triumphal march of death. |

In the six days of her illness Luise had leeches applied to her chest once, on Sunday 29 December, barely a day before she died.

Her brother Ernst's suffering lasted longer, nearly sixteen days, and so the doctors had more time to work their repulsive magic on him. He was leeched on his arms on three separate occasions. Towards the end the leech bites ulcerated, becoming black, infected, itchy and painful – yet more misery for the boy in what would be the last days and hours of his life.

Dark spirits of the earth

Rückert's powers of observation and his analytical mind strove to reconcile healing with the vicious substances that were supposed to bring it about.

Shortly after the death of little Luise, he finds himself at the intersection of the spiritual, the purity of his 'angel' now in Heaven, and the corruption of the earthbound and subterranean matter, the 'earth spirits' which had been used on her.

Goethe's Heinrich Faust and his mentor Mephistopheles were the models for the medical practitioners who conjure with these materials. They had made him a co-conspirator in the despoilment of his own child:

| Als ich aus dem Fenster schaute Nach dem wintergrauen Himmel, Wo ein einz'ger Streifen Lichtes Mir die Bahnen schien zu zeichnen, Die mein Engel angeflogen; |

As I looked out of the window at the grey winter sky, where a single strip of light seemed to mark the paths flown by my angel; |

| Fielen meine Thränentropfen, Und ich merkte, daß sie fielen, Nur weil sie auf Gläsern klangen, Die da vor dem Fenster standen. |

My teardrops fell, and I only noticed that they fell because they chinked on the bottles which stood on the ledge in front of the window. |

| Soviel Arzeneiengläser, Mit den myst'schen Signaturen, Zugezählt nach Stund' und Tropfen, Konnten nicht ein Leben fristen. |

So many medicine bottles with mystical signatures, counted out in hours and drops could not eke out a life. |

| Soviel erdentstiegne Geister, Von der Kunst gebannt in Flaschen, Konnten nicht den Tod bekämpfen. Soviel unterird'sche Mächte, Fremd dämonische Gewalten, Über den Beschwörer herrschend, Mußten aufgerufen werden, Eingefangen, um von Banden Einen Engel frei zu machen. [KTL 86] |

So many earthly spirits trapped by artifice in bottles, could not fight off death. So many subterranean forces, alien demonic powers dominating the sorcerer, had to be called up or caught in order to free an angel from its bonds. |

The doctors of the time really were mere practitioners of the black arts, meddling ineffectually with compounds known by their alchemical signatures and measured out and applied in forms that would not be out of place in a conjurer's book of spells. We note in passing that the modern fans of homeopathy still talk of the 'signatures' of substances left in their waters.

Among the many guilt feelings that come with grief is the feeling that all this medical torture was completely unnecessary. Even among the great marvels of modern medicine, many patients and carers still have to confront the decision whether or not medical intervention is necessary. It is ironic that despite Friedrich Rückert's distaste for the medical profession, his second son Karl (1824-1899) would go on to become doctor.

Brutal Nature

Rückert was overcome by helplessness and grief at his loss, at having to watch two small children die. The religious – and Rückert was a convinced Christian – are forced to absolve the maker of the earth and seas by blaming Nature for her barbarity:

Abzuschaffen geschärfte Todesarten,

Abzustellen den Graus der Folterkammern,

War wol unseren aufgeklärten Zeiten

Vorbehalten zu einem Ruhm. Doch leider

Daß unschuldige Menschenleben gleichwol,

Von Krankheiten gespannt auf Folterbetten,

Schwerem langsamem Tod entgegenschmachten!

Ach wenn menschlicher auch die Menschen wurden,

Unsre Mutter Natur, sie ist bei ihrer

Alten heiligen Barbarei geblieben.

[KTL 114]

The abolition of the death penalty, the end of the horror of the torture chamber, were held to be the great fame of our enlightened times. But it is sad that innocent human lives just the same are stretched out on torture beds and face the mortification of a difficult slow death! Oh, even though humans have become more humane, our Mother Nature has kept to her ancient sacred barbarity.

This perceptive remark of Rückert's reveals the state of cultural and intellectual progress in the West at that time. He was of course aware of the progress made during the Enlightenment (roughly 1650-1800), that age of reason which began to break the shackles of bigotry and superstition. But he could not yet see the results of the Scientific Revolution (roughly 1550-1900), which would bring so many benefits to mankind.

In 1834, when the Kindertodtenlieder were being written, the fundamentals of scientific chemistry were only just being laid. John Dalton (1766-1844), the founder of the atomic theory of matter was still alive, and chemistry was finally moving out of the manipulation of earthbound substances, of alchemical 'signatures' and 'affinities'.

Progress in medical science would follow, but too late to help the Rückert children. The treatments they had to suffer would have been familiar to any doctor in the two or even three preceding centuries. Once it started, however, progress was fast: it would be only another century or so before antibiotics were discovered and manufactured and a few pills could have prevented the deaths of Luise and Ernst and the sufferings of the other Rückert children.

Your newborn author was only prevented from being an early adopter of penicillin by his parents' keeping his older brother, then mottled with scarlet fever, well away from him for several weeks. In the family tradition, this banning of the elder son is the explanation of a lifelong sibling rivalry between him and the little upstart. With penicillin having barely entered into general use your author reflects on the deep wisdom of keeping this germ-laden, festering oaf away from him.

Rückert was by no means the only one at that time having bleak thoughts on the brutality of the natural order and the seeming indifference of the Almighty to suffering– can we speak of a Zeitgeist?

Alfred Tennyson's friend Arthur Hallam had died in 1833, the year before Rückert's children, and Tennysons's grief at his loss would lead to the questionings of In Memoriam, with its famous line 'Nature, red in tooth and claw' [Canto 56]. Tennyson, like Rückert, separated God from the Nature he was presumed to have created, allowing them both to give the blame to Nature for its 'holy barbarity'.

The physical reality of death

Rückert had no illusions about the bodily corruption of death and faced that fact square on. When he saw the body of Luise arrayed with flowers in her coffin he did not shun that awful reality:

| Sie haben ganz, o Kind, um das wir trauern, Mit Blumen dich und Kränzen überdecket; Die werden tief nun, wo du liegst gestrecket, Mitmodernd, deinen Leib nicht überdauern. [KTL 37] |

They have covered you over, O child whom we mourn, with flowers and wreaths; they will now decompose in the depths where you lay stretched out and not outlast your body. |

There is a limit to how much of the awful physical reality of death the normal person – let alone the grief-stricken – can be expected to take. Rückert experienced his share of that:

| Ich habe Gott gebeten, Daß oft im Traumgesicht Er lasse zu mir treten Die Kinder schön und licht. |

I have often prayed to God to let my children appear to me, beautiful and light, in a vision. |

| Nun ist erhört mein Beten, O wäre so es nicht! Sie kommen hergetreten Mit Leichenangesicht. |

My prayer was answered, if only it hadn't been! They walked up to me with the faces of corpses. |

| Und wieder muß ich beten: Solang ihr lebenslicht Wie sonst nicht könnt hertreten, Erscheint mir lieber nicht! [KTL 214] |

And once more I had to pray: as long as they cannot appear in the usual light of their lives, they shouldn't appear at all. |

Rückert, father and poet, recorded a terrible moment that took place immediately after Luise's death. It became one of his greatest poems:

| Sie haben dir die Augen Vergessen zu schließen, Die nun nicht ferner taugen Mein Licht zu ergießen. |

They forgot to close your eyes, which are of no more use to flood with my light. |

| Doch nütz' ich ihre Fehle, Und sehe noch immer Im Auge meiner Seele Von Seel' einen Schimmer. |

But I took advantage of their mistake and still see with my soul's eye a shimmer from your soul. |

| Wie hinter Fensterscheiben Sein Liebchen gesehen Ein Liebender, es bleiben Die Züg' ihm da stehen. |

As when the lover sees behind a pane of glass his loved one, her features remain. |

| Er glaubet süß betreten Zu sehn sie noch immer, Wenn sie zurückgetreten Schon längst in das Zimmer. |

He believes he can still see her, even when she has left the room long before. |

| So scheint mich noch die Seele Vom Auge zu grüßen, Wie längst das Leben fehle Von Haupte zu Füßen. |

It seems to me thus that the soul greets me through the eye, though life is missing from head to toe. |

| Vielleicht, eh ganz sie räumte Das Haus, das zu schwache, Daß sie noch einmal säumte Im schönsten Gemache; |

Perhaps, before she completely leaves the house, that is now too weak for her, she tarries once more in the beautiful room; |

| Daraus noch einmal blickte Ins irdische Leben, Eh sie den Flug beschickte Um höher zu schweben. |

And looks once more at earthly life before she takes flight to higher things. |

| Und ists nicht drin die deine, Die Seele, die stralet, So mag es seyn die meine, Im Spiegel gemahlet. |

And should there be nothing of your soul left that shines, may be it is mine, caught in reflection. |

| Solange noch beseelet Ein schmerzliches Brennen Dein dunkles Aug', entseelet Nicht kann ich dich nennen. |

As long as a painful burning still inhabits your dark eyes, I cannot call you dead. |

| Solange mich beseelet Mit Schmerzen das Brennen Des dunklen Augs, entseelet Wie kann ich dich nennen? [KTL 78f] |

As long as the pain of that burning of your dark eyes inhabits my mind, how can I call you dead? |

Even the exceptionally mild winter of that year prompted thoughts of the physical reality and the finality of the grave for his dead children:

| Winter, der du jetzt im Norden Frühling lügst, mit Schmeichellüften Kannst du doch nur Blumen morden. |

Winter, you who now in the north feign spring with caressing breezes, you can only murder flowers, though. |

| Ungefroren ist die Erde, Daß zu meiner Kinder Grüften Leichter sie erwählet werde. |

The soil is not frozen, thus my children can be laid in their graves more easily. |

| Blumen in den Staub zu strecken, Das vermagst du, nicht mit Düsten Blumen aus dem Staub zu wecken. [KTL 230] |

You can bury flowers in the dust, but not wake flowers from the dust with dusts. |

Let's not deny Rückert, a poet capable of recording such stark sights, his occasional elevation into hope for his children's place in heaven. He had, according to his wife, 'a religious sense' and 'a great love': [KTL 7f]

| AUF DEM KIRCHHOF Eure Geister sind nicht hier zugegen, Wo die Todten ihre Todten legen. Doch die Gegenwart auch eurer Leiber Fühl' ich nicht in diesen Grabgehegen. Daß ihr läget unter diesen Hügeln, Das zu glauben kann mich nichts bewegen. Wäret ihr mir leiblich nah, es müßte Mir im Herzen ein Gefühl sich regen. Doch ich fühls, mit Leib zugleich und Geiste Seid ihr aufgeschwebt dem Licht entgegen. [KTL 479] |

IN THE CHURCHYARD Your spirits are not here, where the dead lay their dead. And I do not feel the presence of your bodies in this graveyard. That you might lie under this mound, I cannot bring myself to believe that. Were you near me in body, a feeling would make itself known in my heart. But I feel, with body as well as spirit, that you have flown towards the light. |

Despite his rationalist conviction that the children he has lost are not in any sense present in their graves in the churchyard, combined with his faith in their place in heaven, it was not easy for Rückert to separate himself from the physical remains of the dead and from whatever spiriti loci seemed to remain:

| Soll ich nun die Stadt verlassen, Wirds nicht schwer mir fallen, Meinen Abschied kurz zu fassen Von den lebenden allen. |

Were I to leave this town I would not find it difficult to make brief my farewell from the living. |

| Aber schwer wird mir das Scheiden Von zwei lieben Todten; Noch von fernher sei den beiden Lebewohl geboten. … [KTL 393] |

But the separation from the two beloved dead will be hard; even from afar the two will be bid farewell. |

At other times the pain of loss forced the rationalist mind to seek refuge in comforting poetic conceits. Such inconsistency is the chief reason we have chosen the live-blogging metaphor to describe the creation process of the Kindertodtenlieder. Rückert – thankfully – did not revise his work. It was left in an almost stream of consciousness state.

In the following poem, for example, Rückert elevates the graves that hold the decomposing bodies of his children to the status of their protectors. The winter had been mild, but the spring of 1834 was cold and windy. A day of bad weather led Rückert to a dark reflection of helplessness and hope.

| In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus, Nie hätt' ich gesendet die Kinder hinaus; Man hat sie hinaus getragen, Ich durfte dazu nichts sagen. |

In this weather, in this storm, I would never have sent the children out; they were carried out and I could say nothing against that. |

| In diesem Wetter, in diesem Saus, Nie hätt' ich gelassen die Kinder hinaus, Ich fürchtete, sie erkranken, Das sind nun eitle Gedanken. |

In this weather, in this tempest, I would never have let the children go out, I would have feared that they would have sickened, those are now vain thoughts. |

| In diesem Wetter, in diesem Graus, Hätt' ich gelassen die Kinder hinaus, Ich sorgte, sie stürben morgen, Das ist nun nicht zu besorgen. |

In this weather, in this awfulness, I would never have let the children go out, I would have worried that they would have died the next morning, there is nothing to be done about that now. |

| In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus, Sie ruhn als wie in der Mutter Haus, Von keinem Sturm erschrecket, Von Gottes Hand bedecket. [KTL 416] |

In this weather, in this storm, they rest as though in their mother's house, frightened by no storm, sheltered by God's hand. |

Mahler fans will have recognised this as the text of the fifth and last of his settings of the Kindertodtenlieder.

The artefacts of loss

After the deaths of Luise and Ernst, Rückert's life is filled with physical reminders of what once was, as well as with the presences of the departed and the shadows of their former existence. For the bereaved, everything becomes a reminder of loss. The Kindertodtenlieder contain numerous examples of this universal phenomenon of grief.

| Zur heiteren Stunde fehlet ihr, Zum fröhlichen Bunde fehlet ihr. Den Sommer kündigen Schwalben an, Der freudigen Kunde fehlet ihr. |

In the cheerful moment you are missing, in the happy group you are missing. The swallows announce the summer, at the happy news you are missing. |

| Die Blumen im Wiesengrunde blühn, Dem blühenden Grunde fehlet ihr. Mit lachendem Mund gehn Rosen auf, Mit lachendem Munde fehlet ihr. |

The flowers in the low meadow are flowering, from the flowering earth you are missing. With smiling mouth the roses open, with smiling mouth you are missing. |

| Gefunden hat Glück und Lust die Welt, Zum glücklichen Funde fehlet ihr. Die Brüder schlingen den Reihentanz; Warum in der Runde fehlet ihr? |

Happiness and joy have discovered the world, from the happy discovery you are missing. Your brothers weave through the dance; why are you missing in the round? |

| Die Mutter erzählt ein Mährchen schön; Warum bei der Kunde fehlet ihr? Ihr fehlt, ich weiß nicht, warum ihr fehlt; Aus nichtigem Grunde fehlet ihr. |

Mother tells a beautiful story; why during the telling are you missing? You are missing, I do not know why you are missing, for no good reason you are missing. |

| Ihr fehlt uns in jedem Augenblick, In jeder Sekunde fehlet ihr. Ihr fehlet an jedem Ort, nur nie Dem Herzen als Wunde fehlet ihr. |

We miss you at every moment, at every second you are missing. You are missing at every place, only from the wound in the heart are you never missing. |

| Was fehlt dem Herzen? ihr fehlet ihm, Damit es gesunde, fehlet ihr. [KTL 209] |

What is wrong with the heart? He is missing you. In order to heal him, you are missing. |

The abandoned Christmas tree

Here, for example, Rückert notes the desolate state of the Christmas tree, left over when Christmas was so brutally interrupted by illness and death.

| O Weihnachtsbaum, O Weihnachtstraum! Wie erloschen ist dein Glanz, Wie zerstoben ist der Kranz, Der um dich den Freudentanz Schlang zur Weihnachtsfeier. |

O Christmas tree, O Christmas dream! How snuffed out is your radiance, how shattered the wreath around which the Christmas party dance circled. |

| O Weihnachtsbaum, O Weihnachtstraum! Der du noch an jedem Ast Halbverbrannte Kerzen hast; Denn wir löschten sie mit Hast Mitten in der Feier. |

O Christmas tree, O Christmas dream! That on every branch you still carry half-burned candles, for we put them out quickly in the middle of the party. |

| O Weihnachtsbaum, O Weihnachtstraum! Jeder Zweig ist noch beschwert, Und kein Naschwerk abgeleert. Ach, daß du so unverheert Überstandst die Feier. |

O Christmas tree, O Christmas dream! Every twig is still weighed down and no treats have been eaten. Oh that you survived the party so untouched. |

| O Weihnachtsbaum, O Weihnachtstraum! Mit den Früchten unverzehrt, Mit den Kerzen unversehrt, Steh, bis Weihnacht wiederkehrt, Steh zur Todtenfeier. |

O Christmas tree, O Christmas dream! With the fruit uneaten, with the candles undamaged, stand until Christmas comes again, stand for the service of remembrance. |

| O Weihnachtsbaum, O Weihnachtstraum! Wenn wir neu dich zünden an, Kaufen wir kein Englein dran; Unsre beiden Englein nahn Drobenher zur Feier. [KTL 201] |

O Christmas tree, O Christmas dream! When we light you again we will buy no angel: our two angels will come here for the party. |

The empty beds

Among the worst of the physical reminders were the children's empty beds. In a wondrously clever poem, Rückert moves the two children from their earthbound empty beds into their aerial afterlife:

| Seh' ich eure Bettchen Beide stehen leer, Wird das Herz mir schwer; In dem Ruhestättchen Regt es sich nicht mehr. |

When I see your empty beds my heart becomes heavy; in the place of rest, nothing moves any more. |

| O ihr Amorettchen, Seid ihr ausgeschlüpft, Habet abgestrüpft Das zu lockre Kettchen, Das euch uns verknüpft! |

Oh you little cupids, emerge from your beds, slip off the chains, too loose, that bind you to us! |

| An des Zaunes Lättchen Sah ich dunkelbraun So zwei Puppen, traun, Leer, und zwei Silphettchen Flogen übern Zaun. [KTL 385] |

On the plank of the fence I saw two dark brown pupae (truly!), empty, and two little moths flew over the fence. |

We are in the presence of a world-class linguist and philologist who taught himself forty or so languages with scholarly precision. Modern readers need a bit of help in untangling Rückert's clever and for him quite characteristic wordplay.

The genesis of the conceit at the heart of this poem appears in stanza no. 55 of his series of three line poems Dreizeilen-Hundert, which also form part of the Kindertodtenlieder. German prosody knows the form under the name Ritornell.

There Rückert wrote: Blüh', Amorellchen! / Im Bettchen schläft ein goldnes Amorettchen, Hat ein Goldammerchen zum Schlafgesellchen., 'Flower little cherry! / In the bed sleeps a little golden Cupid, with a yellowhammer for company'. The amorelle (or amarelle) in the diminutive form Amorellchen refers to one of the many varieties of the sour cherry, Prunus cerasus. [KTL 284]

In the present poem (now separated from the other in this edition by a hundred pages) he develops and expands that imagery.

The first stanza shows us the empty beds left behind by the dead children. There is a clever paradox between the Ruhestättchen, the place of quiet, where now 'nothing stirs'.

In the second stanza we are told that the empty beds used to be occupied by the two Amorettchen, little Cupids, who have slipped the chains that bound them to the family. In a general context ausgeschlüpft would mean hatched, but in this specific context it should be read as 'emerged' [from their resting places] to slip their loose chains.

In the final stanza, Rückert transforms the image of the two empty beds in the house into two empty pupae cases (Puppen) hanging on the garden fence. The two 'little sylphs' flying away 'over the fence' can be taken literally to be moths (the etymology for this is complex and not altogether clear) or spirits of the air.

The greater allegory, in the context of their deaths, is the flight 'over the fence' as the transition between the world of the living and the world of the dead.

We now realise why Rückert used the rather odd word ausgeschlupft to describe the escape of the two little Cupids in the preceding stanza: it prefigured their hatching as moths or spirits from their pupae and thus their departure – their slipping free – from their beds.

The poet takes his reader into a world of metaphors and metamorphoses – transitions from inside to outside, hatching into a new, more beautiful forms and existence, souls escaping from earthbound matter and flying over the fence that separates the earthly from the heavenly.

In another poem – at a lower level of etymological complexity although still with a characteristically Rückert-like complex scheme of rhyme and repetition – Rückert notes the light that has both literally and metaphorically gone out of his life. This appears to be one of the poems which Rückert wrote from the point of view of the mother:

The night-light

| Es brannt' in meiner Kammer Ein Lämplein sonst bei Nacht, Das ging nun aus, o Jammer, Das hat der Tod gemacht. |

In my bedroom a little lamp burnt in the night, that has now gone out, O misery, Death did that. |

| Es brannte für die Kleinen Das Lämplein in der Nacht, Daß sie nicht sollten weinen, Wenn sie mir aufgewacht. |

It burned for the little ones, the little lamp in the night, that they would not cry, when they woke me up. |

| Sie schliefen ohne Weinen, Und sind nie aufgewacht, Doch gerne ließ ich scheinen Das Lämplein in der Nacht. |

They slept without crying and never woke up, but still I let it shine, the little lamp in the night. |

| Ich sah bei seinem Scheinen Gern wenn ich aufgewacht, Wie ruhig meine Kleinen Fortschliefen in der Nacht. |

I gladly saw by its light when I woke up, how quietly my little ones slept on in the night. |

| Nun hat man meine Kleinen Gebettet außerm Haus, Ich lösche nun mit Weinen Das nächtge Lämpchen aus. |

Now my little ones have been bedded outside the house, I extinguish, weeping, the night lamp. |

| Wozu noch sollt' es scheinen? Die Bettchen stehen leer, Ich seh' darin die Kleinen Im Schlaf nicht lächeln mehr. [KTL 224] |

What is the point of it shining? The beds stand empty, I no longer see the little ones smiling in their sleep. |

The children's book

Those who have suffered bereavement will not need to be reminded of the fact that everyday life continues after the loss, leading often to bitter ironies. After the death of Luise and Ernst, a children's book, of all things, arrives for them:

| Fünfzig Fabeln für Kinder, Mit anschaulichen Bildern, Nett von Spekter gezeichnet, Für die Jugend geeignet, Hast du, Freund, mir empfohlen, Und ich ließ sie mir holen. |

Fifty fables for children, with attractive pictures nicely drawn by Speckter, suitable for the young – you, friend, recommended it to me and had it delivered. |

| Leider zu spät empfangen! Denn inzwischen gegangen Sind die beiden, für deren Jahre die Fabeln wären; Ihre Augen verdrossen Sind den Bildern geschlossen. |

Unfortunately, received too late! For in the meantime they for whom the fables were intended have gone; their eyes unenthusiastic are closed for the pictures. |

| Und die übrig gebliebnen, Schon zur Schule getriebnen, Müssen an den Vokabeln Kauen phädrischer Fabeln, Die nicht Zeit ihnen lassen, Sich mit Deutsch zu befassen. |

And the remaining children, already sent off to school, have to chew on the vocabulary of Phaedrus' fables, which will leave them no time to study German. |

| In der Lage der Sachen, Was ist also zu machen? Selber in meinen alten Händen will ich behalten Diese kindischen Mährchen Für mein kindisches Pärchen. |

In the state of things, what can be done? In my old hands I shall keep these childish stories for my childish pair. |

| Kommt im nächtlichen Schweigen, Laßt die Bilder euch zeigen, Euch vorlesen die Reime! Und die Lust, die geheime, Hab' ich, euch an den Augen Abzusehn, was sie taugen. |

[Ernst and Luise,] come in the silence of the night, have the pictures shown to you, the rhymes read aloud to you! And from the secret pleasure that can be seen in your eyes I shall know what they are worth. |

| Wo das Köpfchen ihr schüttelt, Diese habt ihr bekrittelt; Wo ihrs senktet und höbet, Diese habt ihr gelobet; Und gern theil' ich in allen Stücken euer Gefallen. [KTL 347] |

The ones where you shake your head you will have criticised, where you nod up and down you will have praised; and I shall be happy to share your pleasure in all the fables. |

The book was Fünfzig Fabeln für Kinder, which had been first published in 1833 and was, thus, 'hot off the press'.

The author of the fables, Johann Wilhelm Hey (1789-1854), a vicar and school inspector in Thuringia, remained anonymous in the first edition, merely the name of the illustrator, the Hamburg artist, Otto Speckter (1807-1871), was on the title page. Hence Rückert's sole attribution to the illustrator 'Spekter'[sic].

The book and its sequel remained a bestseller throughout the 19th century and even into the early 20th century. A digitalisation of a facsimile edition from 1920 is available on Wikisource, a good digitalisation of an 1852 edition is in the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Rückert, despite being a classical philologist, orientalist and astounding polyglot, was a German patriot and a great champion of the German language. Thus, thinking of the school education that his remaining children were undergoing, with Hey's attractive book of fables in front of him, he takes a dig at the fables of Phaedrus (20BC?-50AD?) that were used in the schools of the time to teach Latin, leaving them 'no time to study German'.

Every modern parent can relate to Rückert's agonized imagining of a reading session much as it had been before, but this time shared with the ghosts of his dead children. In the phantasmagoric session, when the dead children appear to him in the 'silence of the night', he can show them the pictures and read them the rhymes aloud. He would judge their opinions from their eyes and the movements of their heads.

Rückert gives us a memory of one of his readings or recitations to Luise and Ernst:

| O wie ich nun so einsam bin, Wenn meine Großen sind zur Schule, Wo sonst mir blieb mein kleiner Buhle, Und meine Nebenbuhlerin, Die beiden, stets in Einigkeit, Und über nichts als das im Streit, Sich mir zu zeigen dienstbereit! |

O how lonely I am now that my bigger children have gone to school, where otherwise only my little lover and his rival remained. Both of them always in agreement and only battling to show who was the most willing! |

| Sie sitzen so mir noch vorm Sinn, Wie rechts und links von meinem Stuhle Im Stühlchen saß mein kleiner Buhle, Und meine Nebenbuhlerin. Sooft er küßte meine Hand, So zupfte sie mir am Gewand, Alsob sie Eifersucht empfand. |

In my mind they still sit right and left of my chair, my little lover and his rival. Whenever he kissed my hand she tugged on my robe as though she were jealous. |

| Ich nahm die Schmeicheleien hin, Und sang zum Dank das Lied von Thule: Wie lauschte da mein kleiner Buhle, Und seine Nebenbuhlerin! Nun sind sie fort im Schattenheer, Gefallen ist die Krön' ins Meer, Und nie mein Becher thränenleer. [KTL 222] |

I took in the flattery and sang in gratitude the song of Thule: how my little lover listened and his rival! Now they are gone into the army of shadows, the crown has fallen into the sea and my goblet is never empty of tears. |

Here Rückert recalls reciting Goethe's ballad Der König in Thule to Luise and Ernst. The ballad, although it also has an existence as a standalone poem, found its final resting place in Goethe's Faust I [lines 2759–2782], where it is a song sung by Gretchen whilst she is getting ready for bed. Franz Schubert set the song to music in 1816 (D 367).

Both on its own and in the context of Faust, the ballad is a rich source of symbolism and interpretation, too rich for us to discuss here. Over time, the story of the ballad was picked up by other writers and became a fixed point in the German literary canon.

In the ballad, the King of Thule is given a golden goblet by his dying lover, his Buhle. He made good use of the goblet at every meal, emptying it with tears in his eyes for his dead love. When his turn came round to die, he disposed of all his riches among his heirs but kept the goblet for himself. At his death he drank from the goblet one last time then hurled it into the sea.

Rückert not only references Goethe's ballad directly in the last stanza of his poem, his intensive and unusual use of der Buhle for Ernst and die Nebenbuhlerin for Luise is also a clear allusion. The modern usage of der/die Buhle and particularly der Nebenbuhler/die Nebenbuhlerin is rather unpleasant, but Rückert's usage is the older meaning that Goethe would also intend – a 'lover'. In this case, therefore, a male lover and his female rival for their father's affections.

Now his adoring children have gone into the army of shadows, the king's crown – in other poems he referred to his children as his crown – has been lost into the sea, but he is left to fill the goblet with his tears.

Notches in the doorposts

The dead depart and leave behind not just the memories of them that remain with the living but the physical artefacts of their former existence. Here, for example, Rückert meditates on the height marks that had been cut into the doorposts every half year to follow the growth of the two children.

| An der Thüre Pfosten waren Angezeichnet eure Maße, Und wir freuten uns zu sehen, Wie in jedem halben Jahre Ihr um eine halbe Spanne Oder eine ganze wuchset. |

On the doorposts your height was marked and we happily saw how in each half-year you grew by a half or a full span. |

| Scheidend trat der Tod nun zwischen Unsre Freud' und euer Wachsen, Und nicht werden an den Pfosten Eure Maße höher steigen. |

Death has now stepped between our joy and your growth, and your markers on the posts will never go any higher. |

| Aber gleichsam um auf eine Art - ach eine schlimme Art - uns Zu entschäd'gen, hat der Würger Euch nun auf die Sterbebettchen Hingestreckt um eine ganze Spanne länger als ihr lebtet. |

At the same time to compensate us in some way – ah, a bad way – the strangler Death has now laid you out on your deathbeds a whole span longer than when you lived. |

| Soll das etwa dafür gelten Euern Eltern, um ein ganzes Oder halbes Jahr des Lebens Euch im Tode nachzumessen? [KTL 323] |

Is that somehow for your parents, so they can measure in death a year or half-a-year of your life? |

Children's clothes

More physical reminders of what once had been are the clothes of the two children. Since Luise and Ernst were the youngest in the family, their clothes and shoes will not be passed down but preserved as they are.

It is possible that these two poems are also among those written in the persona of the mother:

| (1) Hier lieg' in der Truhe, Was euch angehört; Heilig sei's und ruhe, Wie ihr, ungestört. |

Here in the chest lie your belongings. Let them be sacred and rest, like you, in peace. |

| Kleidchen in der Truhe, Leibchen in dem Grab. Eure Kinderschuhe Tretet ihr nicht ab. |

Clothes in the chest, body in the grave. You will never wear out your children's shoes. |

| Täglich aus der Truhe Nehm' ich Kleid um Kleid, Daß dem Herzen thue Wohl das sanfte Leid. |

Daily from the chest I take out garment after garment, that the heart feels the gentle suffering. |

| (2) Weil ihr wart die kleinsten Bleibt ihr unbeerbt; Euern Staat, den feinsten, Ließt ihr unverderbt. … [KTL 339] |

Because you were the smallest, they will not be handed down; your Sunday best, the finest, you will never spoil. |

Staat is a now obsolete term for what might be called in English the children's 'Sunday best'. As already noted, the Rückerts produced another three surviving children – were these clothes ever handed down? Who knows?

Shadows and shades

The family house, once noisy with six children, has now gone quiet and is filled with shadows.

| Man merket kaum im Hause Die schwebende Schaar, So still ists, wo vom Brause So laut einst es war. |

One hardly notices in the house the floating crowd, so still it is, where once it was so loud. |

| Ihr weiten Räume schienet So voll, nun so leer, Seit euch zur Füllung dienet Von Schatten ein Heer. [KTL 44f] |

You large rooms appeared so full, but are now so empty, serve only now to be filled with an army of shadows. |

Even when the surviving children arise from their sickbeds, they, too, move around the empty house like shades:

| Als von den vier Todeskranken Zwei nun aus den Bettchen stiegen Und durchs Zimmer wieder wanken, Kehren erst mir die Gedanken, Daß zwei andre draußen liegen. |

When two of the four deathly ill now climb out of their beds and wobble through the rooms the thoughts come back to me that two others lie outside. |

| Man hat sie hinausgetragen, Und ich hab' es wohl gesehn; Doch ich dacht' in diesen Tagen Immer noch, daß alle lagen, Um mit einmal aufzustehn. |

They were carried out and I saw it, yet I still thought in these days that all of them lay [in their beds], to arise sometime. |

| Nun zerronnen ist der Traum, Aufgestanden sind nur zwei, Schatten gleich, man hört sie kaum, Schleichen sie im leeren Raum, Sonst gefüllt von Lustgeschrei. [KTL 151] |

Now the dream has faded, only two got up, like shadows, you hardly hear them, they creep around in empty rooms that were once filled with shouts of joy. |

A pair of extremely moving poems describe the emptiness left by the loss of Luise.

In the first of these, Luise's place has been taken by shadow. Reality and imagination are mixed skilfully: the shadow is not her ghost, but the absence of light left by her own absence:

| (1) Wenn zur Thür herein Tritt dein Mütterlein Mit der Kerze Schimmer, Ist es mir als immer, Kämst du mit herein, Huschtest hinterdrein Als wie sonst ins Zimmer. |

When your mother comes through the door, with the candle's shimmer, it seems to me as though you came in with her, flitting just behind her as always in the room. |

| Träum' ich, bin ich wach, Oder seh' ich schwach Bei dem Licht, dem matten? Du nicht, nur ein Schatten Folgt der Mutter nach. Immer bist du, ach, Noch der Mutter Schatten. [KTL 77] |

Am I dreaming, am I awake, or is my sight failing me in this light, this dimness? Not you, but only a shadow follows behind your mother. You still are, oh!, your mother's shadow. |

| (2) Wenn dein Mütterlein Tritt zur Thür herein, Und den Kopf ich drehe, Ihr entgegen sehe, Fällt auf ihr Gesicht Erst der Blick mir nicht, Sondern auf die Stelle Näher nach der Schwelle, Dort wo würde dein Lieb Gesichtchen seyn, Wenn du freudenhelle Trätest mit herein Wie sonst, mein Töchterlein, O du, der Vaterzelle Zu schnelle Erlosch'ner Freudenschein! [KTL 77] |

When your mother comes in through the door and I turn my head to look at her, my glance does not fall on her face but rather on the place closer to the threshold, there where your lovely face would be when you entered happily with her as always, my little daughter. Oh you, the ray of light in your father's room, too soon extinguished. |

This pair of poems was made famous as one of the five Kindertodtenlieder that were set to music by Gustav Mahler between 1901 and 1904. For some reason, Mahler reversed the order of the poems, which means that his setting begins with poem no. 2.

The Rückert family house is full of the shadowy presences of the two children who have passed on:

| Es ist kein Fleckchen Im Hause weit, Kein dunkles Eckchen Ist weit und breit, Aus dem hervor nicht dränge Und mir entgegen spränge Von Zeit zu Zeit Eins meiner beiden Geckchen. |

There is no place in the big house, no dark corner wherever, out of which from time to time one of my two little monkeys did not rush out and jump at me. |

| Es ist kein Streckchen Im Gartenraum, Kein Rosenheckchen, Kein Strauch, kein Baum, Aus dem hervor nicht klänge Und mir entgegen sänge Ein schöner Traum Von meinen beiden Reckchen. … [KTL 349] |

There is nowhere in the garden, no rose hedge, no bush, no tree from which noise emerged and sang me a beautiful dream of my two little heroes. |

Following the sheep

In former springtimes, Luise and Ernst could not be restrained from joining the shepherd taking the sheep out early in the morning and bringing them back in the evening. Now they are both dead, this ritual is one more painful memory for their father:

| Es waren meine Kindchen Zu halten nicht im Haus, Wann mit dem Schäferhündchen Die Schafe zogen aus. Sie hüpften mit den Lämmern Durchs Feld im Abendschein, Und trieben dann beim Dämmern Sich mit der Herd' auch ein. |