Doris Leuthard: smiling through

Posted by George Meredith on UTC 2019-01-24 11:04

The art of political drudgery

Among the five and a half billion adults living in the world there may be a few who are not completely familiar with the political system of Switzerland. We need to deal with this surprising knowledge deficit before we can proceed with our review of Werner Vogt's new book Doris Leuthard - Die Staatsfrau mit Charme und Charisma.

First point to remember: the Swiss political system was designed with the lesson of that frightful French rascal Napoléon Bonaparte in mind, its main purpose being to prevent autocrats ever gaining power. In that respect it seems to have worked – in the years since 1848, when the Swiss Confederation was founded, there is no record of any Swiss politician bestriding the world. No Swiss politician has marched into Russia in the winter. Two things, nota bene, which cannot be said for that other small country at the heart of Europe, Austria, unfortunately.

The Swiss system does this by subjecting all its politicians to immense amounts of drudgery. If politicians are busy reading and signing stuff, they have no time to get up to mischief. If, in addition, they have no time to think, then that is all to the good – idle hands make work for the devil.

The most highly regarded Swiss politicians, therefore, are the ones who have the neatest political filing cabinets – tidy labels on the drawers, all the files where they should be and no half-eaten packet of biscuits in the bottom drawer. And in Switzerland there are ranks of such filing cabinets everywhere. Every group of hamlets, every village or town has a Gemeinderat, a 'local council', elected by voters, with rows of filing cabinets to fill and maintain. There is no escape: any village that is too small to be able to fill enough filing cabinets on its own is merged with nearby villages into a Bezirk, a 'borough', until a respectable quantity of filing cabinets have come together.

Each of the 26 cantons has its own constitution with rows and rows of well-stuffed filing cabinets in its own executive, parliament and administration. A canton and the towns within it are in permanent, busy administrative uproar regulating each other.

At the national level the cantons are represented in the Ständerat, the 'Cantonal Council' (~'Senate'), the 46 members of which are elected by the voters of their cantons (more filing cabinets).

Separately from this, voters elect the 200 members of the Nationalrat, the 'National Council' (~House of Representatives / Commons) who have even more filing cabinets – many, many more, in fact.

The millions of twitching arms and legs sticking out from underneath this political and administrative mountain are the voters – tauntingly called the 'Sovereign' – who are bidden to go and vote for something or someone at the local, cantonal and national level every quarter. The hero of Austerlitz would find all this just as debilitating as the Russian winter.

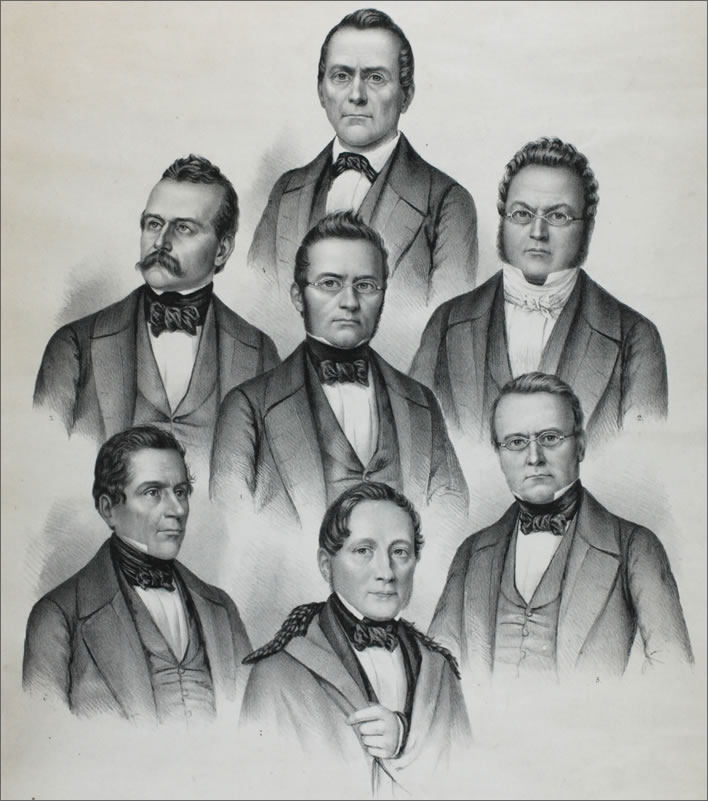

The old guard

Finally, above it all, there is the Bundesrat, the executive 'Federal Council', the seven members of which – chosen by the members of both the Nationalrat and the Ständerat– are elected every four years to look after the even more gigantic pile of filing cabinets that makes up the government of the Confederation of Switzerland.

Each of the seven Bundesräte has an army of civil servant sherpas to convey files from all the various filing cabinets and dump them pitilessly on the Bundesrat's desk. At some time in the late evening the sherpas will remove the files from the haggard, sunken-eyed figure at the desk and put them back in an orderly manner where they belong. The procedure begins again at seven o'clock the next day.

In the UK system the Prime Minister these days is Napoleonic and can generally do almost anything he or she wants to. Members of Parliament are supine donkeys who bray loudly but ultimately, in the hope of favours, do whatever they are told. In the US system the President is also Napoleonic and can do many things through executive orders but, more generally, whoever has got the majorities gets their way to do what they want.

In Switzerland, in contrast, whatever a Bundesrat might care to do has to be done with the consent of the federal parliament, the cantons and the towns, but, even when they are squared, some troublemaker will launch a referendum in an attempt to roll the dice in a different direction. The measure of success of a Bundesrat's career, apart from the tidiness of the filing cabinet, is the proportion of referenda that have been won.

Even during the Second World War, when plucky little Switzerland was surrounded on all sides by the Axis powers, there was no fun to be had: no charges, counter-charges, pitched battles, grenade throwing – no Where Eagles Dare stuff at all. Its army occupied mountain fortresses and its leaders wrote memos for each other's filing cabinets. No 'blood, sweat and tears' – just ink, paper and filing.

Becoming a Bundesrat requires the victim to grunt and grind his or her way up the perilous Eiger North Wall of filing cabinets. The new member joins the existing colleagues at the summit. Those who manage this epic feat were long before their arrival reduced to being emotional and intellectual cripples who have been cured of all thoughts of grandeur.

Just to make sure that no little Napoléon has arrived at this point unmasked, each Bundesrat takes turns being the federal president for a year and is allowed a little time away from the desk to go and shake hands with foreigners. Even at this height, apart from the occasional glass of warm white Swiss wine, they are not supposed to enjoy themselves.

A few years ago, one Bundespräsident got into very hot water for reviewing, as an act of politeness, a military guard of honour which the Italians, as an act of politeness, had set up in welcome. Far too much like fun – memories of Napoléon surfaced and in the ensuing scandal the Bundesrat in question got a severe telling off. Quite right, too. Stick to filing cabinets.

The Colleagues Grim

When Bundesräte, gaunt and sallow, finally step down from these political peaks the greatest praise that they ever get is that they kept their filing cabinets tidy. Nor must they resign too early: a Bundesrat who cannot hold out for at least two terms is considered to be a failure. And the resignation speech must also include sober praise for all the sherpas who kept the victim busy and out of mischief.

They get paid well for their servitude – nearly half-a-million Swiss Francs a year and half of that amount in perpetuity for their pension when they retire from the Bundesrat. They can also expect a range of easy stocking-fillers that require them to hang around company boardrooms for an hour or two a month without making nuisances of themselves. Apart from a salary and pension that is not to be sniffed at, why any person would want to do this job is a mystery to the sane.

The first Bundesräte after the founding of the Confederation of Switzerland in 1848 had plenty to do in the young nation, but a century and a half later, the immense growth of the areas regulated by the state in modern, technological and globalised nations has meant that the administrative load on Bundesräte is now simply immense – superhuman, in fact, because the number of files that have to be processed is well beyond the capacity of normal humans.

The 1848 Bundesrat: Serious men for serious times. Image: Zentralbibliothek Solothurn.

It also means that more and more of the pre-processing is being done deep in the entrails of the administrative state, the civil servants who have the keys to the filing cabinets. Digitalisation has not reduced the number of filing cabinets but has merely added a further layer demanding attention – on top of which come rolling news and online media twenty-four hours a day and seven days a week.

The reader will not be surprised to learn that, until quite recently, nearly all Bundesräte looked grim: jaws firmly clenched, unsmiling, blank eyes in sunken sockets. Up to the early 1990s, that is, when they started to have their group photos taken and little by little pasted rictus grins on themselves.

So far the men have kept off the mascara, but in these days of colour photography a little bit of blusher helps hide grey cheeks sunken with care. Before that, men generally kept their ancient teeth out of sight behind their clamped lips and did nothing to encourage the suspicion that what they were doing was in any way enjoyable.

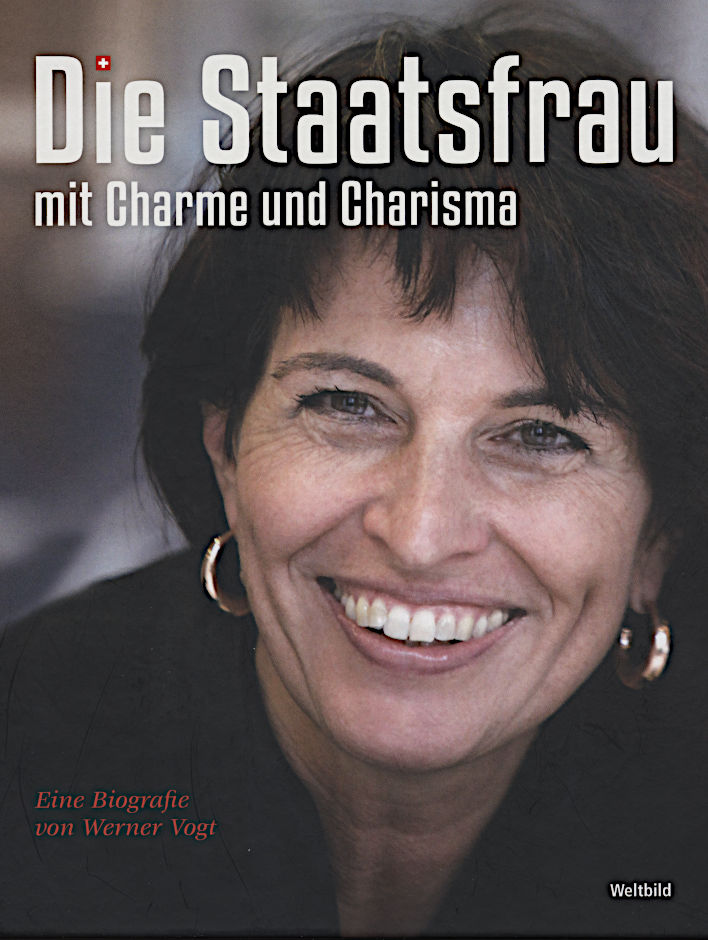

Our Doris

Then, in 1997, a starburst illuminated the grey clay army of Swiss political life: Doris Leuthard. Big hair (raven), big eyes (brown), big teeth (pearly, but not annoyingly perfect) and a smile and – for heaven's sake! – a laugh to match the teeth. A women out of a Visconti film, perhaps, except that they never laughed. This one did – all the time.

Doris Leuthard. Image: ©UVEK

She wasn't just a magnificent set of teeth, though. In her 34 years of life up to that point she had been formed by a deeply Swiss background – the perfect political background, in fact.

Born in 1963 in Merenschwand, a village in Canton Aargau, she was raised with three brothers in a family of hard-working parents who were rooted and active in the community. Her father was the 'Gemeindeschreiber', 'town clerk' of the village, her mother had run a restaurant in a neighbouring village. In such villages each individual is known to everyone else, transparent lives without secrets – schools, clubs and societies.

Merenschwand, Aargau, Switzerland. Birthplace and family home of Doris Leuthard. Base image: Swisstopo.

Wherever we look, the transparent Doris Leuthard comes over as an innately 'good' and humane person, as do the other members of her family. We detect no 'edge', no foibles, no Napoleonic tendencies at all. Inculcated with Christian values, armed with charm, self-effacement, great emotional intelligence and that formidable smile, we find her getting on with everyone. As she grew up she developed a talent for conciliation and cooperation. She became simply 'Our Doris'.

When she was 19 she began to study Law at the University of Zurich, coming back home every weekend. She went on study trips to Paris and Calgary. She speaks her local Swiss-German dialect (of course), acceptable High German (not always the case in Switzerland). Her French was good, her English, too, her Italian excellent (she has relatives in the Italian-speaking Tessin) – in short, she fulfilled all the requirements for a position at the national level of polyglot Switzerland: grounded in Heimat whilst being federally open.

After she graduated in 1989 she got a job in a legal practice not far from her home village, becoming a partner in 1991. She also took on some local functions such as a school governorship. Summing up: by the time she was 28 she was at the start of the sort of a solid legal career about which the great mass of people can only dream. At that point she entered the world of professional Swiss politics.

The Doris

She came from a Catholic family and her natural political home was the CVP, the Christian Democratic People's Party', a traditionally Catholic party. It took the local party managers no time at all to spot this star in their midst.

It was a time of change, a time of greater media awareness and a time particularly for the advancement of women. In Britain 'New' Labour got elected under the grinning leadership of Tony Blair and brought in a relatively large number of female ministers.

In Switzerland in 1997, Doris Leuthard was elected to be a member of the Parliament of Canton Aargau. With that she stepped on the elevator of the Swiss political system, the right person at the right time, loaded with refreshing political charisma and a big smile. From then on the elevator would ping its way upwards rapidly.

In 1999, two years after she had become a Kantonsrat, she was elected to the Nationalrat, even though her name was the last on her party's list of candidates. In a proportional representation system the party's old guard and trusties get the first places, the newbies and the hopeless cases are then tacked on at the end, the expectation being that the latter will keep offering themselves up at every election until they either move up the list and get elected to something or just drop dead and make way for other foot soldiers.

In Doris' case, not only did the last on the list get elected straight away, immediately after her election she became deputy leader of her party and glided through the layers of grumbling, party intrigue and backstabbing to become the party's president in 2004. And finally, in 2006, 43 years old, she was elected to the grey ranks of the Bundesrat. Lara Croft was entering the crypt of the undead.

The 2017 Bundesrat. Doris Leuthard was President of Switzerland for the second time in that year and got to design the team photo. The question of whether the iconography alludes to the 1848 image of the Bundesrat or the famous cover of Queen's Bohemian Rhapsody is unresolved. Doris was an impressionable twelve in 1975 when the record appeared, so some deep pre-teen memory may have surfaced here. The sinister, shadowy figures along the bottom are not a good idea, though. Image: Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft.

In nine years, therefore, Doris Leuthard went from the bottom to the top of the Swiss political pile. Even more startling, it only took 17 years from her graduation in 1989 for her to become a Bundesrat, only slightly longer than the 14 years that Bonaparte took from his graduation to become First Consul. Respect!

In Swiss terms, this is an astonishingly rapid ascent – it is speed climbing, in fact, the political equivalent of a mountaineer climbing the Eiger North Face in a couple of hours. The 'Leuthard effect' was real. Just one silly example: consider the fact that now, whenever a camera is anywhere in the vicinity, Swiss politicians are all grinning like The Joker, Batman's adversary – the Leuthard effect in a nutshell.

In 2018 we thought we might have reached peak idiocy with the then president Alain Berset's effort… Image: Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft.

…unfortunately, the 2019 photo ran it very close. Image: Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft.

With characteristic charm and honesty she makes no secret that being a woman at a time when women were needed to make up the numbers was an advantage. She notes that in her career no male opposing candidate was ever selected over her. On the occasion of her election to the Bundesrat, she had no opponent at all. 'Top floor: Ladies' Haberdashery!'

We need to talk

The other focus in the Swiss constitution is upon conflict resolution.

Before 1848, when the federal constitution was introduced, Switzerland had been the Wild West of Europe. Since the Habsburgs departed all those centuries ago there had been no dictator to impose universal order. Bonaparte's brief autocratic intervention between 1798 and 1814 was even welcomed by many Swiss as a way of imposing order and some legal universality.

Following Bonaparte's deposition the Swiss experienced more than thirty years of turmoil. After Napoléon had finally left for Saint Helena, the Swiss had to resolve their differences as best they could. The 1848 constitution had to cope with cantons, cities, towns and language regions vying with each other for some advantage or other.

The process of conflict resolution that is at the heart of the Swiss constitution has given the world the famous 'Swiss compromise'. Even these days the Swiss government likes to put itself forward as the honest broker in international conflicts.

In a recent example, a Swiss team was on hand to spend the next fifty years (at least) glacially triangulating nuances around the North Korean 'Rocket Man'. In this case though, 'The Donald' did the job himself in under a week, it would seem.

Second only to the management of a filing system, therefore, the most valuable skill for any Swiss politician is the ability to get all involved parties to agree to whatever squared circle is required. Doris Leuthard has this talent.

Who is Doris, what is she?

Doris Leuthard. Image: ©UVEK

It could be said of Doris Leuthard that she is the perfect modern Swiss politician because she is a principle-free zone. Werner Vogt's biography – without going to our extremes of criticism – gives us numerous examples of what she personally believes – as far as she tells us, that is.

Politics may be the 'art of the possible' and Doris Leuthard's political success has been in sensing what are feasible, implementable policies. But, apart from being nice to everyone, what does she believe?

Who knows? And, in any case, what difference would it make? Belief counts for nothing when there are filing cabinets to be curated.

Werner Vogt quotes a telling comment made by a political opponent after her election as the President of the CVP in 2004: 'She exudes a certain charisma, but politically she has no profile. This means that the CVP will continue to muddle along as it has done up to now, but just with a bit more charm.'

Vogt manages to give us some hints to her beliefs: In her youth she nearly joined the FDP, the (very nominally) free marketeers and business party. During her stay in Paris she was shocked at the top-down centralisation of the French political and administrative system. In 1999, at the time she became a Nationalrat, she was for the legalisation of cannabis, controlled abortion, gay marriage and joining the EU. We simpleton observers might assume that the second and third of these, combined with twenty years of living in sin with the man whom she finally married in that year, might cause the Catholic base of the CVP some heartache. It did, a little bit – but it is amazing what you can do with a nice smile. She was and apparently still is a supporter of nuclear power.

Werner Vogt devotes quite a few pages to Doris Leuthard's political positioning during her years as a Bundesrat. It's a difficult task. One measure of political success for a Bundesrat is to count how many referenda were 'won' or 'lost' – that is how many of them delivered results that agreed with her policies. In other words: was she on the right side of the voters.

On the purely numerical measure she has done astonishingly well: her departments were involved in eighteen referenda during her period in office and lost only two of them. Yet this measure can be misleading.

In referenda, winning or losing may be a matter of just a few percentage points. The 2018 referendum to abolish broadcast licence fees was 'lost' by the margin of a rounding error. It is in the nature of Swiss referenda that even only five or ten point differences can traditionally be termed 'clear' decisions. This means that there are often a large number of losers who have to go along with that Swiss compromise for the sake of political peace. That's how the system works.

When the result is close, the fine art of Swiss muddling through comes into operation. In the close run referendum on the broadcast licence fee, for example, the hated money collector was abolished, a money collector with a new name was set up and money is now being extracted with menaces in just the same way as before. The rounding error that won the vote is the winner that takes all.

But those of us who are not Swiss find it rather odd that in the Swiss system, all principles – things that one believes to be right – are disposable commodities, at least for a member of the Bundesrat. In Leuthard's case, very disposable. She appears to have a brain which can tolerate any quantity of cognitive dissonance between what she believes and what she advocates.

Cuddling Junker, embracing the EU

For example, Our Doris, the young free-marketeer who was shocked by French centralised control, nevertheless wanted Switzerland to join the European Union, that ziggurat erected to the greater glory of French and German central control. We scratch our heads: how can these two be reconciled?

In an interview with Vogt she expresses her belief that there could be a special form of membership of the EU for states such as Switzerland, the Balkans(!), Turkey(!) and Georgia(!).

For anyone with the slightest knowledge of the history, goals and workings of the EU, such a suggestion coming from such a high-ranking politician is breathtakingly absurd, especially since the EU, in the person of Jean-Claude Junker himself no less, treated Switzerland with such contempt in 2017, when Our Doris was taking a turn as the Federal President. Her lovey-dovey public behaviour with Juncker on a visit during that time was seen by many to be quite inappropriate to the office she held.

She doesn't seem to realise that there is no sliding scale of EU integration. Membership is digital, as the United Kingdom is currently discovering during Brexit: a nation is either in – in which case it effectively ceases to exist – or it is out – in which case it is a 'third country' such as New Zealand or Bangladesh. There is nothing to triangulate, nothing upon which to compromise. If a country is in the EU customs union it must renounce entirely its own trading sovereignty; if a country is in the single market it must renounce nearly all of its own governmental scope for the sake of the 'four freedoms'. There is no way that the EU will ever allow Switzerland to cherry-pick its advantages. We are not sitting around the kitchen table in Merenschwand discussing who should get the last piece of carrot cake.

To be fair, Doris Leuthard is not alone amongst the deluded of Swiss politics in respect of the European Union. Some time ago we discussed the muddled and contradictory opinions of a former Bundesrat, Pascal Couchepin, who also seems to expect a union of 28 states to bend its rules to suit the Swiss gnat in its midst.

The Swiss tsunami

Another example of discarded principles is nuclear power, in which, we are told, she believes. That belief made no difference, for after the Fukushima accident in 2011, caused by a tsunami, she made no defence of her own beliefs in the face of the demonisation of atomic power in Switzerland, a place where tsunamis are rare (except for little ones in mountain lakes).

The disaster was cranked up and instrumentalised by the socialists and greens. She and her party, despite their beliefs, put up no resistance to the scare stories that were put forward for the shutdown of the existing nuclear reactors in Switzerland, but crumpled before them, setting Switzerland off down the same Energiewende road that had by that time already brought Germany to the edge of energy ruin.

The Swiss government had already allowed itself to be overrun by climate alarmists and would turn up, the climate Goody-Two-Shoes, at every climate conference and sign up without question to whatever was on offer. Whenever it was pointed out that Switzerland's sacrifices would make no measurable difference to either the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or the associated putative climate change, the answer was always the same: Goody-Two-Shoes, a rich society, must set an example that the poor will follow.

Doris Leuthard's lack of understanding of even the broadest strokes of the climate and energy debate is exemplified by her choice of ministerial car: a Tesla – arguably one of the most polluting motor vehicles in the world.

The referendum that she 'won' on this topic achieved a 'considerable' (stattliche, NNZ) vote of 58 percent on a turnout of 42 percent. That's a Swiss 'considerable', by the way, meaning that eight percent of those voting were the decisive factor in sending Switzerland down a path of expensive energy from erratic sources and a great dependency on foreign sources to provide baseload, its 'modern clean energy future'.

To outsiders it seems that Leuthard and her department did not rationally scrutinise the proposal, they simply worked out how best to get it through a referendum. In building the consensus behind Leuthard's energy referendum the palms of many interest groups were crossed with taxpayer silver. And, of course, Leuthard's smile worked its old magic. It also has to be said that the opponents to Leuthard's plan were even more intellectually unfocused than its proponents.

It's a Swiss thing: a referendum is no place to sort out large, complex, multidimensional, technical issues. We can't blame Our Doris for that – she has to look after her filing cabinets as best she can. But her career, so accessibly documented here by Werner Vogt, is a warning for what is to come in Switzerland. Laughing hubris has now vacated the field, grim faced Nemesis is already on its way.

Administrative schizophrenia

At some point the ability to ignore cognitive dissonance turns into full-blown schizophrenia. During her time in charge of UVEK, the giant Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications, the free-marketeer side of her personality laid the ground for an opening of the electricity market. We free-marketeer bill-payers applaud her blessed memory!

Currently Swiss households are bound to buy their electricity at a protectionist tariff from certain 'clean' sources – meaning principally hydroelectric generation. Businesses have more flexibility and can opt for a tariff that gives them whatever electricity is cheapest. The opening of the market would allow householders, too, to choose the cheapest tariff.

It must have been clear to the green do-gooder side of her personality that the cheap stuff is the overflow imported from German and French nuclear power and coal generators. When the wind is blowing in the North Sea and the sun is shining down, the Germans have to keep their baseload generation turning over, ready for the moment when the wind stops blowing and some clouds drift by. This surplus Dreckstrom, 'dirty electricity' from coal and nuclear is sold at knock-down prices over the various international interconnectors.

Thus we have the irony of Goody-Two-Shoes, clean-energy Switzerland, not only buying cheap filth but becoming reliant on it. Leuthard's open market would allow private households to consume this stuff, not just businesses. Expensive hydroelectric power just cannot compete.

It has also been clear for a long time that Switzerland's transition to clean energy will only work when backed up by increasing amounts of imported power. Switzerland has no reserves of coal, oil or gas, even if they could bring themselves to burn it. Germany and France, the chief sources of that power at the moment are also in the course of scrapping their nuclear and coal generation. Some magic Swiss pixie-dust will be needed to square that circle sooner than most people think.

The brain of Doris Leuthard was clearly unaffected by such schizophrenic situations. Her successor, Simonetta Sommaruga, the socialist pianist, now has to try and implement the market liberalisation proposal whilst preserving her green credentials. As a socialist she is by nature averse to free markets, so the cognitive dissonance is probably much less.

We can sense that balm for schizophrenics – a Swiss compromise, being slurped on thickly: the prices of imported power will be artificially inflated so that the consumer can choose. Although there is really no choice. Something is wrong here.

The Swiss technology gap

How can the Swiss political system, built on the three pillars of consensus, muddling through and referenda, meet the challenges which the present – let alone the future – is throwing at it?

These challenges are presenting themselves in every field of government. They are highly complex and technological in nature. They all contain a degree of uncertainty and risk. If all the measures to meet these challenges have to survive the consensus of the colleagues in the Bundesrat and the dice-rolling of a referendum, then the future for Switzerland looks bleak.

There are currently no members of the Bundesrat with a background in science or technology. Such a background was always an unsuitable place to begin the thankless climb up the Eiger North Wall of filing cabinets. We grumbled about this deficit in technological expertise in relation to the foolish introduction of the Swiss-ID.

You doubt this? Here are the current Bundesräte and their backgrounds: Ueli Maurer SVP, commercial apprentice; Simonetta Sommaruga SP, pianist; Alain Berset SP, political scientist; Guy Parmelin SVP, Latin/Wine grower; Ignazio Cassis FDP, doctor; Viola Amherd CVP, lawyer; Karin Keller-Sutter FDP, interpreter and teacher. Three or more centuries of the Scientific Revolution have left no trace on the current Swiss government.

Well, you say, they will certainly have lots of clever people on their staff. Indeed – which is exactly the problem. In the end, they do what their specialists tell them to do, because they are in no position to argue.

The common position that the Bundesrat as a whole has to support on each issue is, on technological matters, really just an unquestioning acceptance of an individual Bundesrat's sheep-like acquiescence in their own specialists' opinions.

The Bundesrat currently in charge of UVEK, the department that Doris Leuthard has just vacated, is Simonetta Sommaruga, the socialist pianist without higher educational qualifications, assisted by yet another female lawyer from the CVP. Before her change of department, Sommaruga was the Bundesrat pushing the idiotic Swiss-ID.

Since 1995, this department has been run by two socialists and Doris Leuthard of the CVP. The first of these socialists was Moritz Leuenberger, a self-confessed believer in the political expediency of the Noble Lie. There can be no doubt that in the intervening quarter-century the civil servants in this department have been appointed to match the political tastes of the Bundesrat in charge.

Doris: the last of the line or the new beginning?

And how will the consensual Swiss system cope with the extreme political divisions that are growing in every developed country, Switzerland included? Doris Leuthard achieved much with a smile and lots of charm. Her successors in the Bundesrat, however much they grin on their photos, will find that success ever more difficult to attain.

Werner Vogt is not afraid to take on complex materials and make an engaging story out them, as he demonstrated in his last book SWISS – Die Airline der Schweiz, which we reviewed last year.

This time round the complex materials are the early life and political times of Doris Leuthard. The book is no hagiography: the author interviews family, friends, political friends and political enemies, asking questions that are sometimes quite probing. The successes are there – as are the failures. Doris Leuthard comes out of the biography as an engaging, charismatic yet grounded figure whose many successes were well deserved. The account of her formative years is a particular highlight of the work.

This is no biographical doorstop packed with footnotes. However it covers the ground readably and would be the biography of choice for the interested citizen of whatever political colour. The illustrations are well researched and well chosen. Your reviewer – not a Leuthard fan as you may have gathered early on in this review – nevertheless found Werner Vogt's account to be fair and in some places very illuminating. He is glad he read it – and he never thought he would write that about a biography of her.

The narrative content of the book – an engaging text with many excellent illustrations – has unfortunately fallen into the hands of a graphic designer who believes that what the world wants is pale grey body text, sometimes even on a pale grey background. There is no visual delineation of quotations, meaning that the reader is frequently unsure whether the words come from the author or someone else. In case pale grey text is not difficult enough to read, most subheadings are in an equally difficult to read bright-red condensed sans-serif face. Fortunately, the narrative force of Werner Vogt's text carried your reviewer along right to the end. Perhaps the eBook will be more legible.

Werner Vogt, Doris Leuthard - Die Staatsfrau mit Charme und Charisma, Weltbild Verlag 2018, 160 Seiten, Gebunden, Deutsch, ISBN-10: 3038127620, ISBN-13: 9783038127628. Available from Weltbild Verlag.

Dr Vogt is an occasional contributor to Figures of Speech on his specialist subject Winston Churchill.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!