The Lesbia poems

Posted by Richard on UTC 2019-07-16 14:04

The temporal jumble

Before we can start our reading of Catullus' 'Lesbia poems' we have to restate an absolutely immutable fact about the collection of poems as a whole: the poems are in no particular thematic or chronological order.

It will be clear to those heroic readers who stayed awake during our review of the genesis and transmission of the Catullan text that the text we now have was probably assembled from an unknown collection of an unknown number of rolls into the form of a codex at some unknown time in the fourth century AD (probably). It seems clear that this was not an editorial process but a rescue process.

Robinson Ellis, the great 19th century editor of the Oxford edition of Catullus, in the second edition of his 1889 Commentary on Catullus was in no doubt on this point:

The poems of Catullus fall at once into three main divisions, the shorter lyrical poems I-LX, the long poems LXI-LXVIII, the Epigrams: or if we again divide the longer poems into Elegiac and non-Elegiac into four, I-LX, LXI-LXIV, LXV-LXVIII, LXIX-CXVL. As this arrangement is obviously metrical, it is a priori improbable that the poems as a whole follow a chronological order.

Ellis, Robinson. A Commentary on Catullus, Oxford, 1889, p. xlv.

He goes on to give numerous examples of poems that are out of any conceivable temporal sequence.

The same iron logic applies to the Lesbia poems, which are embedded throughout the work as raisins in a spotted dick. The order of these poems is effectively random. Thus Julia Dyson's 2007 article on them is doomed to failure from the very first paragraph:

Much of the richness and strangeness of Catullus lies in his unsettling, brilliant decision to tell the 'story' of his relationship with Lesbia all jumbled up, with poems about falling in love long after poems about breaking up, and poems on a variety of other topics interspersed.

Julia T. Dyson, 'The Lesbia Poems' in Skinner, Marilyn, ed. A Companion to Catullus, Blackwell, 2007. p. 254.

After this initial deranged acceptance of the jumbled up chronology of the poems and even a justification of it as an artistic masterstroke, Dyson goes on to derive many rich and strange speculations from the positions of particular poems in this bogus sequence.

The reality is, however, even richer and stranger. Consider a chess board with its pieces lined up ready to start a game. Knock it up in the air, sending the pieces tumbling down the back of the sofa. We retrieve what we can find from behind the cushions and put them back on the board.

Only a non-chess player would consider two pawns, a bishop, three more pawns, two knights, a pawn and a queen a valid opening disposition for a game of chess, let alone an arrangement worthy of a grand master. The other pieces remain irretrievably lost in some deep crack where normally only the remnants of the snacks of yesteryear and a few obsolete coins reside.

The reality is that we have a collection of poems whose order, leaving aside the metrical grouping that Ellis identified, is chronologically pseudo-random – an order no different from writing the titles on scraps of paper and throwing them up into the air in front of a fan. This order has been sanctified by Dysons down the centuries, meaning that we are going to need all our resolve to treat it as the imposter it really is. Let's do it.

Someone's sparrow

The group of Lesbia poems is identified as a group because somewhere or other the name Lesbia occurs in them. Except that this is not true: not only do several poems that are traditionally assigned to the group not mention her name directly, but – irony of ironies – two of these are regarded as the two jewels in the crown of the Lesbia group: the 'sparrow poems'.

Those two poems are among the most famous and widely anthologised of Catullus' poetry, yet Lesbia is not only not mentioned, the affect and tone of address of the two poems is substantially different to those of the other, named, Lesbia poems.

The two sparrow poems are charming and fine pieces of work, but as we study the other Lesbia poems we will come to appreciate that Catullus' relationship with the sparrow girl is simply not of the same order as his relationship to Lesbia.

Down the generations both scholars and their readers have assumed that Lesbia was the great love of Catullus' life and that (on no evidence whatsoever) he had only that one great love. In which case the hot chick with the sparrow must ipso facto be Lesbia.

But Catullus was not a one girl guy, nor was he an idiot – he was a masterful poet and metrical stylist who has been highly regarded by his poetic peers down the centuries. Again and again in his poems he tells us just what we need to know to construct the esse of the poem – and no more. There is no superfluity in Catullus' work.

Conversely, he does not hide necessary things from the reader. We must approach each Catullan poem in the spirit that everything is there that needs to be there for a contemporary to understand the poem. We are not his Latin contemporaries so sometimes we need a bit of assistance, but the general rule is valid: everything is there.

The two 'sparrow poems' make no reference at all to Lesbia and offer no credible circumstantial evidence of her presence. That should be a clear signal to us: these poems are not about Lesbia. Catullus didn't just forget to put her name in or try to hide from us the invented name of which he makes so much in his real Lesbia poems.

Nor does the fact that this pair of poems happens to be in the vicinity of some poems in which Lesbia is named mean anything – we slap our foreheads and repeat our guiding principle number one of Catullan studies: the poems are in no particular thematic or chronological order. Conclusion: the sparrow poems do not concern the woman he called Lesbia.

Nevertheless, we shall look at them here because they are so famous and writers down the centuries have written of 'Lesbia's sparrow'… but they are not Lesbia poems.

C 2: The pet sparrow as distraction therapy

Sparrow, darling of my girl, with which she plays, which she presses to her bosom, to whom she gives her fingertip, arousing sharp bites as he seeks after it, when gleaming with desire of me she jests a light joke of it, so that, I think, it is a solace for her pain when the heavy burning is at rest. Could I but play with you just as she does and lighten the sad cares of mind. […] This was as pleasing to me as the golden apple was to the fleet footed girl [Atalanta], which unloosed her girdle long-time fastened.

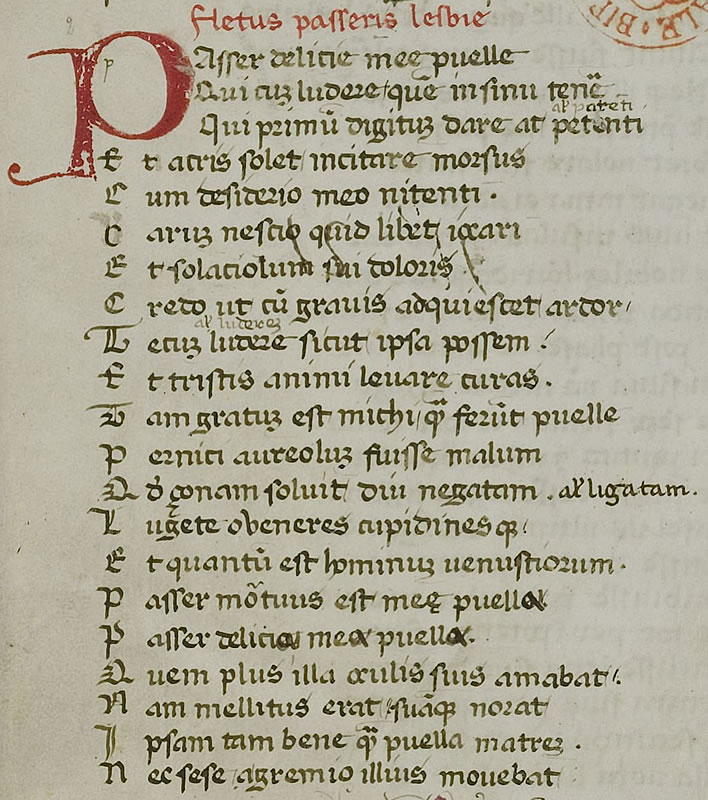

Passer, deliciae meae puellae, / quicum ludere, quem in sinu tenere, / cui primum digitum dare adpetenti / et acris solet incitare morsus, / cum desiderio meo nitenti / carum nescio quid libet iocari / (et solaciolum sui doloris, / credo, ut tum gravis adquiescat ardor), / tecum ludere sicut ipsa possem / et tristis animi levare curas! …Tam gratum est mihi quam ferunt puellae / pernici aureolum fuisse malum, / quod zonam solvit diu ligatam.

[c 2]

Editorial note: The three lines following the ellipsis clearly do not belong in this poem. Merrill hypothesises a single missing line at the ellipsis that would be the glue that somehow joins the tail to the body. Your author's admittedly limited brain can think of no line that could possibly do this, so different are the sentiments of the two parts (in the first part of the poem both boy and girl are 'gagging for each other' – no artificial aids such as apples would be required to loosen this girl's girdle). The poem surely stops at Catullus' wish to find some similar distraction from his own raging passions: at this point the poem is complete: a single concept roundly expressed in verse – there is no superfluity in Catullus' verse.

Note that the poem is addressed to the sparrow, not the girl. The complexity and elegant urbanity of this little poem is striking. The sparrow is the object that takes the girl's mind off her raging desire for Catullus – without the bird they would undoubtably both swing into action on the spot. We might expect our amorous poet to blame the avian gooseberry for spoiling his fun, which he probably does in his heart, but instead, the urbane poet wittily wishes only for a similar distraction for himself.

[c 2] Image: BnF, Manuscript G, 1r.

The second of the two 'sparrow poems' is thematically linked to the first only by the presence (in death) of the sparrow and of its tearful mistress. A sequence is implicit though: Carmen 3 has to follow Carmen 2, for we have a living sparrow then a dead sparrow, but this does not necessarily mean that the two poems have to be next to each other.

C 3: Eulogy for a dead sparrow

O mourn, you Loves and Cupids, and all men of gracious mind. Dead is the sparrow of my girl, sparrow, darling of my girl, which she loved more than her eyes; for it was sweet as honey, and its mistress knew it as well as a girl knows her own mother. Nor did it move from her lap, but hopping round first one side then the other, to its mistress alone it continually chirped. Now it fares along that path of shadows from where nothing may ever return. May evil befall you, savage glooms of Orcus, which swallow up all things of fairness: which have snatched away from me the comely sparrow. O wretched deed! O hapless sparrow! Now on your account my girl's sweet eyes, swollen, redden with tear-drops.

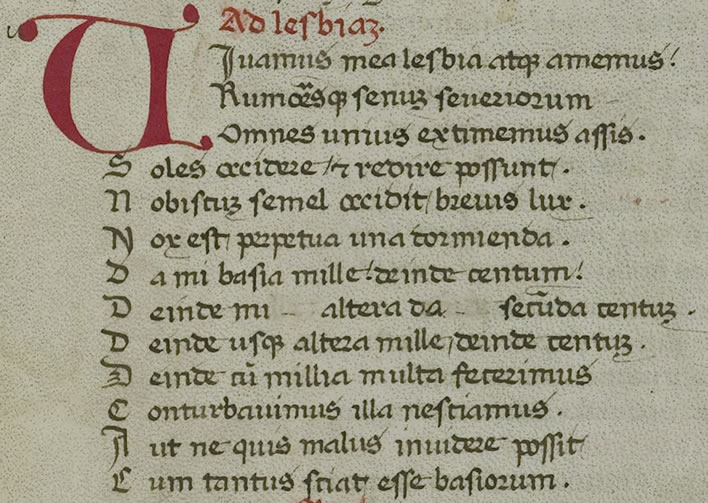

Lugete, o Veneres Cupidinesque / et quantum est hominum venustiorum! / passer mortuus est meae puellae, / passer, deliciae meae puellae, / quem plus illa oculis suis amabat; / nam mellitus erat, suamque norat / ipsa tam bene quam puella matrem, / nec sese a gremio illius movebat, / sed circumsiliens modo huc modoilluc / ad solam dominam usque pipiabat. / qui nunc it per iter tenebricosum / illuc unde negant redire quemquam. / at vobis male sit, malae tenebrae / Orci, quae omnia bella devoratis; / tam bellum mihi passerem abstulistis. / o factum male! o miselle passer! / tua nunc opera meae puellae / flendo turgiduli rubent ocelli.

[c 3]

Both poems, although linked by some associations, are quite independent and could stand alone or be separated widely by numerous other poems. If we only possessed Carmen 2, we would never miss Carmen 3 or imagine that such a poem existed. Ditto for Carmen 3.

Sparrow and girl are in both poems, but the messages of the two poems are quite different. In the first poem the sparrow offers distraction from other, more urgent desires; in the second poem, all such desires are gone – meaning that the moods of the two poems are completely different, too.

There is, however, one strong allusion in the second poem to the first, the repetition of the phrase passer, deliciae meae puellae, 'sparrow, darling of my girl', from the first line of the first poem.

The poems are also interdependent in more subtle ways. Suppose that in the first poem of the pair, instead of expressing the urbane wish to have his own distraction sparrow to take his mind off the act of darkness, Catullus had vented his annoyance at the little bird for getting in the way of the fulfilment of his passion. Had that been the case, the lament for the sparrow's death in the second poem of the pair would scarcely have been possible.

Having said all that, we mustn't take Catullus' funerary oration for his girl's dead sparrow too seriously, though. The hard-hearted cynics who infest this website may prefer a more satirical reading, not only of the bombastic, formulaic praise of the sparrow's virtues followed by the ritual imprecations against the underworld and death's savagery in the present poem, but also the simpering account of the annoying little nonentity in the first of the two poems who thwarts the poet's deepest desires with its silly antics. Satire at its finest.

In this reading the two poems are indeed very closely linked and indeed belong next to each other. And the simple girl who had nothing deeper in her head than messing about with a sparrow probably believed the poet's words of consolation, too – job done!

Thank goodness for our cynical readers – we've got our Latin poet back!

The Lesbia poems

Now that we have thrown out the two sparrow poems, our task in the following is to extract the remaining Lesbia poems from this inchoate jumble of a poetry collection and attempt to restore them to some temporal and psychological coherence – what the songwriter Paul Simon termed 'the arc of a love affair'. We may make a few mistakes but, quite frankly, any sequence will be better than the present shambles.

Light petting, no tongues

Let's start with what we might consider to be the easy bit: passion.

Except there isn't any – at least nothing that wouldn't be considered tame at a senior-school dance. On the evidence of these poems, Catullus and Lesbia worked out the behavioural codes for the sixties drive-in movie, two thousand years before that institution was invented.

Catullus, who could spew out obscenities with the best of the writers of the age (Martial, champion in the field of obscenity, learned his skills from Catullus) becomes puzzlingly demure when describing his physical relations with Lesbia. More accurately, the descriptions are just not there. Not one fumble.

After our account of the home life of that other famous poetic pairing, Sextus Propertius (45?BC-15?BC) and his Cynthia, our readers may have been looking forward to similar fireworks between Catullus and his Lesbia. No such luck.

The following two poems, for example, written at the very highest point of Catullus and Lesbia's passionate relationship, could be read by any Sunday School class or by any well brought-up young lady without raising a blush.

C 5: counting kisses, carpe diem

Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love, and count all the rumors of stearn old men at a penny's fee. Suns can set and rise again: we when once our brief light has set must sleep through a perpetual night. Give me a thousand kisses, and then a hundred, then another thousand, then a second hundred, then another thousand without resting, then a hundred. Then, when we have made many thousands, we will confuse the count lest we know the numbering, so that no one can cast an evil eye on us through knowing the number of our kisses.

Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus, / rumoresque senum severiorum / omnes unius aestimemus assis. / soles occidere et redire possunt: / nobis, cum semel occidit brevis lux, / nox est perpetua una dormienda. / da mi basia mille, deinde centum, / dein mille altera, dein secunda centum, / deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum, / dein, cum milia multa fecerimus, / conturbabimus illa, ne sciamus, / aut ne quis malus invidere possit, / cum tantum sciat esse basiorum.

[c 5]

[c 5] Image: BnF, Manuscript G, 2r.

C 7: counting even more kisses

You ask, how many kisses of yours, Lesbia, may be enough and to spare for me. As the countless Libyan sands which strew asafoetida-bearing Cyrene between the oracle of sweltering Jove and the sacred tomb of ancient Battus, or as the many stars, when night is silent, look upon the furtive loves of mortals, to kiss you with kisses of so great a number is enough and to spare for passion-driven Catullus: so many that prying eyes may not avail to number, nor ill tongues to bewitch.

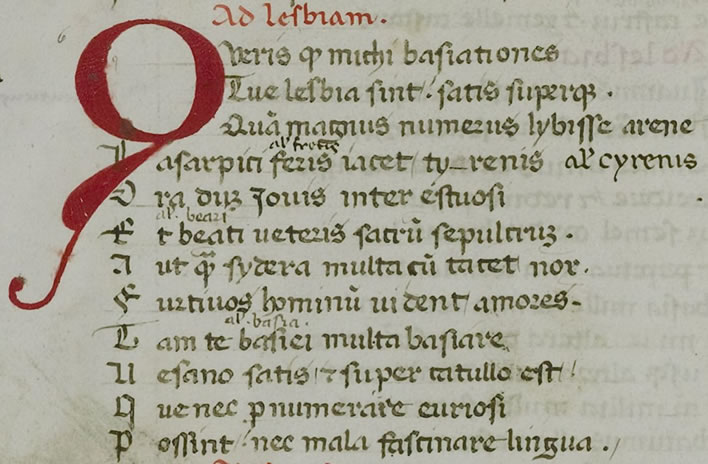

Quaeris quot mihi basiationes / tuae, Lesbia, sint satis superque. / quam magnus numerus Libyssae harenae / laserpiciferis iacet Cyrenis, / oraclum Iovis inter aestuosi / et Batti veteris sacrum sepulcrum, / aut quam sidera multa, cum tacet nox, / furtivos hominum vident amores, / tam te basia multa basiare / vesano satis et super Catullo est, / quae nec pernumerare curiosi / possint nec mala fascinare lingua.

[c 7]

[c 7] Image: BnF, Manuscript G, 2v.

In these two poems the lack of freewheeling passion is certainly a cause for surprise. But equally as puzzling is the underlying paranoia we detect.

In both poems there is some lurking worry of an 'evil eye', of 'prying eyes', 'ill-tongues' and 'bewitching'. It is a mood of furtiveness and fear of retribution that strikes us as odd in the otherwise unrestrained sexual climate of the Roman Republic and the Empire. Admittedly, messing around with another man's wife could have very direct and lethal consequences at that time, so Catullus was probably right to be worried at first. Still, it was only kissing, wasn't it?

The real Lesbia

So far we have gone to considerable lengths to avoid posing the question that has occupied the attention of so many scholars down the centuries: who was the real Lesbia?

We have avoided posing it for two reasons: 1) it is a presumptuous question and 2) it is a pointless question to which there is no satisfactory answer. On this last point we follow Ludwig Wittgenstein: if no answer is possible, why ask the question?

Why is it a presumptuous question? Because Catullus chose to call the female figure in these poems 'Lesbia' – and that is all we need to know. It's a poem, not an autobiography. We are told one further fact about her: she is married, a fact that would explain the furtiveness we noted in the two kissing poems above.

And that's it. Why do we need to know more than the poet tells us?

It is as though we put on a Buddy Holly record: 'If you knew Peggy Sue, then you'd know why I feel blue…', at which point, with one imperious swipe, the pedant sweeps the needle screeching off the vinyl. Who is this 'Peggy Sue'? Is this her real name? How old is she? What does she do? What does she look like?

Absurd questions – demonstrably absurd and pointless, because in this case we do know the identity of the girl who lent her name (but nothing else) to the song and it makes no difference. When we put the needle back on the record – now ruined forever – nothing has changed. Learning that the donor of the name was one Peggy Sue Gerron only relocates the ignorance and annoys the pedant even more: And who was she? And why… Enough.

Hunting for the 'real' Lesbia is as absurd and ultimately pointless as hunting for the 'real' Peggy Sue. The name Clodia has been passed down the ages as the real name for Lesbia. At each telling the supposition has become ever more reified and certain until nowadays it is retailed as a fact by all but the most punctilious scholars. In reality, we know hardly anything more about Clodia herself (or perhaps Clodia's sister etc.) than we do about her literary shadow, Lesbia. Let's forget all about Clodia (and her sister). She is totally unnecessary. We have Lesbia.

The point is that Catullus used an alias for his lover's name and told us as good as nothing about her. He told us nothing about her appearance, her build or that old lovers' favourite, the colour of her eyes. Substituting Clodia for Lesbia brings us not a jot further, since we don't know any of this for Clodia either. Clodia is merely a figleaf to cover our ignorance about Lesbia – and a transparent one at that.

Delicacy

In the next Lesbia poem in the arc, her physical beauty is outshone by the radiant charm of her personality – more proof if we needed it that Catullus explicitly refuses to discuss individual physical characteristics:

C 86: interior beauty

Quintia is lovely to many; to me she is radiant, tall, and straight. Each of these qualities I grant, but deny the whole of these is loveliness: for there is no charm, not a grain of salt in so great a body. Lesbia is lovely, for not only is the whole of her most beautiful, but she has stolen all the Venus-charm from everybody together.

Quintia formosa est multis, mihi candida, longa, / recta est. haec ego sic singula confiteor, / totum illud “formosa” nego: nam nulla venustas, / nulla in tam magno est corpore mica salis. / Lesbia formosa est, quae cum pulcherrima tota est, / tum omnibus una omnis subripuit Veneres.

[c 86]

There is something very alien to Roman poetry going on here: towards Lesbia our poet is lovestruck, respectful, reverential almost. Adoration has displaced lust and the object of desire has become more than a mere body. We begin to suspect as much when we realise how chastely the relationship between Catullus and Lesbia is depicted.

We get the impression that our poet would consider such a listing of her physical attractions as being too vulgar a thing for his lady. This is quite odd, at least in the conventions of Roman erotic poetry.

As the Latin scholar Frank Copley pointed out many years ago, Catullus' lack of descriptions of the things he and Lesbia got up to are bland to the point of seeming abnormal – deviant even – in the obscene whirlpool of sexual life in Rome at the time. He put his finger on the special nature of the coyness we find in the Lesbia poems:

It is precisely an absorption in the non-physical aspects of love that sets Catullus’ love for Lesbia apart from the common run of ancient affairs and gives to it its special character.

It is notable from the very start that nowhere in the Lesbia-poems does Catullus dwell on the joys of physical intimacy — this in the face of his complete lack of reserve in such poems as 32 and 56.

Kisses he mentions, of course, but beyond that there is nothing more immodest in the Lesbia-poems than the almost bashful multa iocosa of c. 8

Copley, Frank O. 'Emotional Conflict and its Significance in the Lesbia-Poems of Catullus' in American Journal of Philology 70 (1949) 22-40, p. 23.

Note: 'multa iocosa' – ibi illa multa tum iocosa fiebant, quae tu volebas nec puella nolebat, 'There those many joys occurred which you did wish, nor was the girl unwilling.'[c 8]

Well, we have seen plenty of kissing action already, but for a quick glimpse at the 'common run of ancient affairs' we can take Copley's hint and look at [c 32], which illustrates the conventional Roman poet's way with a girl:

Please, my sweet Ipsithilla, my delight, my charmer: order me to come to you at noon. And if you should order this, it will be useful if no one makes fast the outer door [against me], and don't be minded to go out, but stay at home and prepare for us nine continuous love-makings [nine times!]. In truth if you are minded, give the order at once: for breakfast over, I lie supine and ripe, [my penis] poking through both tunic and cloak.

Amabo, mea dulcis Ipsithilla, / meae deliciae, mei lepores, / iube ad te veniam meridiatum. / et si iusseris illud, adiuvato, / ne quis liminis obseret tabellam, / neu tibi libeat foras abire; / sed domi maneas paresque nobis / novem continuas fututiones. / verum, si quid ages, statim iubeto: / nam pransus iaceo et satur supinus / pertundo tunicamque palliumque.

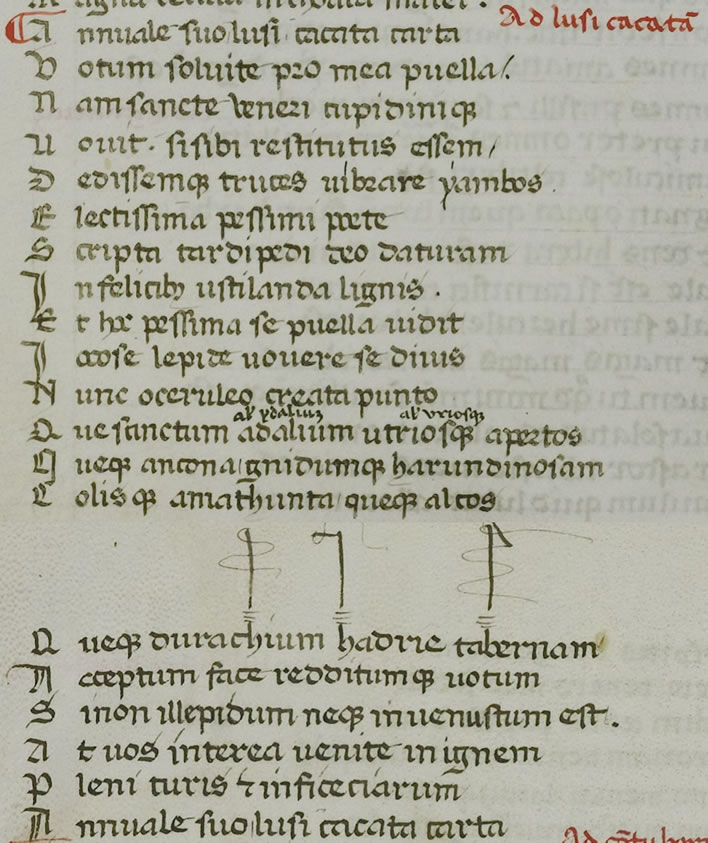

[c 32]

The extent of this strangeness in the Lesbia poems becomes clear in the next two poems we are going to look at, c 109 and c 87. In the traditional Catullan sequence they are far apart, but in fact they belong together – two very brief poems which play a key role in understanding the arc of Catullus' love affair with Lesbia.

The nature of love

C 109: holy friendship

My life, you declare to me that this love of ours will be an everlasting joy between us. Great Gods! grant that she may promise truly, and say this in sincerity and from her soul, and that through all our lives we may be allowed to prolong together this bond of holy friendship.

Iucundum, mea vita, mihi proponis amorem / hunc nostrum inter nos perpetuumque fore. / di magni, facite ut vere promittere possit / atque id sincere dicat et ex animo, / ut liceat nobis tota perducere vita / aeternum hoc sanctae foedus amicitiae.

[c 109]

In [c 109] we find Catullus trying to come to terms with a spiritual love that transcends physicality. Copley gives a very good account of the struggle of our poet to forge a new language to encompass this new-fangled romantic love – a feeling which finally acquired its terminology more than a thousand years hence.

Your author apologises for the length of this quotation, but no paraphrase or digest would do justice to Copley's quite brilliant analysis of this brief poem:

The first hint of the struggle is to be found in c. 109, and lies in the contrast between the first and last distichs of the poem. The experience lying behind it would appear to be something of this sort: Lesbia and Catullus have had a discussion of the nature of their mutual feelings; Lesbia has protested undying love on her side, and has offered to Catullus an amor iucundus perpetuusque.

As Catullus reflects on this discussion, it occurs to him that the phrase Lesbia has used is too hackneyed and ordinary. It does not ring true; more important than that, it does not at all express the feeling that he himself possesses, nor does it describe the kind of love in which he is interested. In legal language, he does not like the terms of the contract she proposes. After, therefore, expressing (vv. 3-4) the hope that, whatever she meant by amor iucundus perpetuusque, she meant it sincerely, he goes on to attempt an expression of what he himself desired.

What he wants is not amor, for that to him means primarily the standard brand of erotic interest. He does not want something merely iucundus, for he sees clearly enough that such a feeling is perpetuus only as long as it remains iucundus.

Rather, he wants a love which is not mere physical attraction, but rather has its basis in a harmony of body, intellect, emotion, and spirit. Unfortunately, no word exists in the Latin language which will adequately express this idea. He tries, therefore, to analyze the feeling itself, to break it up into its component parts, and in that way to find expression for it.

It is, first of all, something that lasts throughout life, and does not disappear with youth and beauty. It is no mere casual connection; it is a bond, covenant, foedus. Perhaps amicitia is the right word.

But amicitia has two faults: it is not normally used of relations between men and women, and it is essentially a cold and formal term. It is adequate only in that it expresses a feeling based on elements that are not physical in nature.

To lift it out of its usual formal sphere, Catullus adds to it the epithet sancta; this, he hopes, will show that he does not mean the ordinary feeling of friendship, but something more exalted in character.

In the end, Catullus’ attempt at expression is not successful; he succeeds only in indicating that his love is no ordinary love, and that amor is not the proper term for it. To the average ancient, as to the modern reader, his aeternum sanctae foedus amicitiae must have remained something of a puzzle.

Copley p. 25f.

The rejection

At some point after days, weeks, months or years – who knows? – Lesbia distances herself from Catullus. The reasons for the distancing are unknown. If our conjectured temporal sequence for the Lesbia poems is correct, this would position the last poem we looked at, [c 109], at the top of the arc of the love affair.

In his wounded state, Catullus continues to wrestle with understanding his emotions and solving the terminological problems of his love affair with Lesbia in [c 87], a poem fragment which can be viewed as a companion piece or extension to [c 109]. We place it after [c 109] firstly, because of the tense in which it is written and secondly, because of the way it represents a philosophical extension to the reasoning in the preceding poem.

This fragment has none of the vituperation we shall encounter later; it is closer in tone to [c 109] and deserves careful attention despite its brevity.

C 87: the importance of trust

No woman can say truly that she has been loved as much as you, Lesbia, have been loved by me: no trust in any pact has ever been found so great as was that on my part in the love of you.

Nulla potest mulier tantum se dicere amatam / vere, quantum a me Lesbia amata mea es / nulla fides ullo fuit unquam in foedere tanta / quanta in amore tuo ex parte reperta mea est.

[c 87]

Now, by disregarding the given sequence of the Catullan poems, we have brought c. 109 and c. 87 together and we are now able to appreciate the intense poetical effort that Catullus is putting in to defining his love for Lesbia – a strange, unsettling feeling for a Roman author (and his readers).

Catullus was breaking completely new ground in exploring his relationship with Lesbia. At least thirteen centuries ahead of his time he was tapping through Latin as a blind man with a stick to express feelings that are quite new for his own times.

Frank Copley, in his analyis of [c 87], outlined Catullus' search for a terminology adequate to describe his feelings for Lesbia:

As if seizing upon this idea of fides as the one phase of his love which he can express with clarity, Catullus, in c. 87, tries once again to formulate his concept of the affection he bore Lesbia.

Leaving aside the term amicitia as essentially unsuccessful, he combines fides with a quantitative rather than a qualitative expression, perhaps in the hope that the two together will more nearly express his meaning.

He tells us in the first distich that no woman can truly say that she has been loved as much as Lesbia has been by him; then, to show that his love was not merely greater in quantity – or intensity – he adds in the second distich: nulla fides ullo fuit umquam in foedere tanta quanta in amore tuo ex parte reperta mea est.

He bore for her, in other words, not merely a passion (amor) that surpassed all others; in addition, his feeling was possessed of a constancy, a trustworthiness, a loyalty (fides) such as no other had ever known.

In this poem, as in c. 109, we gain the impression that Catullus first expresses the nature of his love in more or less conventional terms, and then, finding that expression inadequate, attempts to correct it by adding some element which is unmistakably non-physical – in this case, fides.

Again, just as in c. 109, the amended declaration is unsatisfactory and incomplete: it does not say what Catullus wanted to say. It is no more than a thrust in the right direction, but a thrust that does not reach its goal. Amor and fides together do not completely define his love.

Copley p. 26f.

We have to wait for late medieval Italian, French and Provencal poetry to come along and deliver the terminology for the scholastic analysis of such states and such relationships – readers who know about such things should recall the intense poetic search in the late Middle Ages for the Latin, French, Italian and Provencal words to express the quasi-mystical categories of being that defined the poet's donna – even to its formal statement in a doctrine of courtly love.

The spirit of Romance

The late medieval poets of Italy and France have centuries of Christian mysticism to fall back upon for the terminology to express love and desire. Dante, in his famous account of his first glimpse of Beatrice in Vita nuova, required three spirit aspects – heart, head and bowels – with each of which he had to fall back on church Latin to describe that moment. His head told him: Apparuit iam beatitudo vestra, 'Now your bliss is manifest'.

Beatitudo/beatitas was coined by Catullus' close contemporary Cicero, but used only once by him to represent merely a state of happiness, a state even a dissolute Roman could understand. Beatitudo in the sense in which Dante and Co. used it, though, is far beyond the comprehension of the Roman.

In time the word fell into the hands of Jerome and the other Church Fathers and blossomed through the centuries into a concept that extends far beyond happiness to suggest a state of divine grace.

At the sight of his Lesbia, Catullus perhaps felt a little as Dante did at the sight of his Beatrice, but lacked the words to formulate the feeling – whereas Dante only needed one: beatitudo.

The spirit of metaphysics

Modern students of the Romance poetry of the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance wrestle to bring the mystical doctrines of courtly and non-courtly love into comprehensible English. Readers familiar with English literature may be thinking of the 17th century metaphysical poets, pre-eminently John Donne (1772-1631). These poets were learnèd and had the vocabulary at their fingertips to write amorous poetry full of philosophical subtlety.

A dozen centuries of philosophy and religious mysticism allow Donne, for example, to come up with his numerous expressions of spiritual passion. Let's take the deservedly most famous example, on the inseparability of souls conjoined in love:

[…]

If they be two, they are two so

As stiffe twin compasses are two,

Thy soule the fixt foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if the'other doe.And though it in the center sit,

Yet when the other far doth rome,

It leanes, and hearkens after it,

And growes erect, as that comes home.Such wilt thou be to mee, who must

Like th'other foot, obliquely runne.

Thy firmnes makes my circle just,

And makes me end, where I begunne.

Donne, John (1572-1631). 'A Valediction Forbidding Mourning' (1611?) in Poems, 1633.

Catullus was already almost there: amore, sancta amicitia, foedus, fides.

The breakup

But at some point Catullus starts to become suspicious that what Lesbia says does not tally with what she means or does. It seems to be the first stage of the breakup process. It is beginning to dawn on Catullus, simple man, that Lesbia may not have been totally honest with him:

C 70: a woman's word

No one, says my lady, would she rather wed than myself, not even if Jupiter himself sought her. Thus she says! but what a woman says to a desirous lover ought fitly to be written on the breezes and in running waters.

Nulli se dicit mulier mea nubere malle / quam mihi, non si se Iuppiter ipse petat. / dicit: sed mulier cupido quod dicit amanti / in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua.

[c 70]

True, this poem does not mention Lesbia explicitly, but it fits well with one that does, [c 72], which we shall look at shortly. In the present poem Catullus addresses Lesbia as 'my lady', which leads us to believe that the breakup has not yet taken place fully, that we are hearing just the first rumbles of troubles to come.

It appears that young Catullus, busy pondering on the terminology of his heart, assumed that Lesbia was pondering along with him. Silly boy! It appears that our poet is about to have an encounter with the Female Principle, as another poet and ponderer once defined it:

Two span, two span to a woman,

Beyond that she believes not. Nothing is of any importance.

To that is she bent, her intention

To that art thou called ever turning intention,

Whether by night the owl-call, whether by sap in shoot,

Never idle, by no means by no wiles intermittent

Moth is called over mountain

The bull runs blind on the sword, naturans

To the cave art thou called, Odysseus,

By Molü hast thou respite for a little,

By Molü art thou freed from the one bed

that thou may'st return to another

The stars are not in her counting,

To her they are but wandering holes.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound, 4th collected ed., London, Faber and Faber, 1987, Canto 47, p. 237.

Notes: Two span, two span to a woman, length of penis (How long is a span? Half a penis, of course – silly question!); Molü, the herb that Hermes gave to Odysseus to protect him from the spells of the witch Circe; thou may'st return to another, get back to his wife Penelope; Odysseus, There was an old man called Ulysses / Who wandered o'er hills and abysses; / He met with Calypso / who waggled her hips so, / He was glad to get back to the missus.

But at some point after this, Catullus' suspicions seem to have been confirmed and Lesbia openly rejects him. After the deep ponderings on the quality of his love that we encountered in the previous poems, the wounded Catullus now consoles himself with the sort of light-hearted arguments used by dumped ones down the ages: 1) see if I care! 2) you'll be sorry!:

C 8: rejection (possibly not by Lesbia)

Unhappy Catullus, cease your trifling and what you see lost, know to be lost. Once bright days used to shine on you when you used to go wherever your girl led you, loved by us as never a girl will ever be loved. There those many joys occurred which you did wish, nor was the girl unwilling. In truth bright days used once to shine on you. Now she no longer wants you: you too, powerless to avail, must not want her, do not pursue her retreating, do not live unhappy, but with firm-set mind endure, harden yourself. Farewell, girl! now Catullus hardens himself, he will not seek you, will not ask you since you are unwilling. But you will be pained, when you are not asked. Faithless, go your way! what manner of life remains to you? who now will visit you? who find you beautiful? whom will you love now? whose will you be called? whom will you kiss? whose lips will you bite? But you, Catullus, remain firm in your hardness.

Miser Catulle, desinas ineptire, / et quod vides perisse perditum ducas. / fulsere quondam candidi tibi soles, / cum ventitabas quo puella ducebat / amata nobis quantum amabitur nulla. / ibi illa multa tum iocosa fiebant, / quae tu volebas nec puella nolebat. / fulsere vere candidi tibi soles. / nunc iam illa non vult: tu quoque, impotens, noli, / nec quae fugit sectare, nec miser vive, / sed obstinata mente perfer, obdura. / vale, puella! iam Catullus obdurat, / nec te requiret nec rogabit invitam: at tu dolebis, cum rogaberis nulla. / scelesta, vae te! quae tibi manet vita! quis nunc te adibit? cui videberis bella? / quem nunc amabis? cuius esse diceris? / quem basiabis? cui labella mordebis? / at tu, Catulle, destinatus obdura.

[c 8]

Lesbia is not named, so that it is an assumption that she is the one doing the dumping here. It is a questionable assumption, too, since the style, manner and content of this poem are unlike the other poems that can be clearly associated with Lesbia. We must never forget that, in assigning it here to this position in the arc of the Catullus-Lesbia love affair, we are floating on conjecture, for there are solid arguments on both sides of the decision about whether the poem is about her or not.

On the pro-Lesbia side, line 5 of [c 8], amata nobis quantum amabitur nulla, 'loved by us as never a girl will ever be loved' recalls line 2 of the poem that explicitly mentions her, [c 87] quantum a me Lesbia amata mea es, 'as much as you, Lesbia, have been loved by me'. It would be surprising if these two poems were not chronologically close or adjacent.

We read here, too, that Catullus seems to have been very much his girl's plaything, who did whatever she wished, suggesting that we are dealing with Lesbia's obvious emotional mastery over the lovestruck Catullus.

And yet. And yet. On the contra-Lesbia side of the argument, Lesbia is not named. Why? Not giving us the name of the miscreant strikes us as odd. Once we free from our minds the conventional assumption that this is a poem about Lesbia, the poem can be comfortably read as a standard effort dealing with the rejection by any girl. It could just as well be applied to a rejection by the 'sparrow girl' in [c 2] and [c 3], whom we so unceremoniously ejected from the Lesbia canon, or indeed any of Catullus' flames.

We also have to admit that the poem as a whole gives us no feeling of the heartbreak Catullus reports in other poems after his rejection by Lesbia. Instead the mood is cavalier, matter of fact almost. Where is the lust that increases with contempt? Where is the feeling of betrayal? Can this be the woman whom Catullus loved 'as a father loves his own sons and sons-in-law'?

In the second half of the poem in particular, in the 'you'll regret it' section that begins with 'Farewell, girl!', we are told that the girl will be hurt not to be asked back by Catullus and the rest of her life will be empty and loveless.

This sounds like the ritual boasting of the scorned lover: 'who's sorry now?' Certainly not something addressed to the worldly, married woman he calls Lesbia, whom he will soon excoriate in the most vulgar terms for the social and sexual whirl of her life. Unlike Lesbia, the girl in this poem has not left Catullus for another lover, she has just dumped him.

That ritual boasting provides only the surface of this section of the poem. Who can doubt that beneath the boastful, couldn't-care-less-surface there lies a heart racked with jealousy, tormented by visions of 'his girl' and some future lover who has taken his place: 'whose will you be called? whom will you kiss? whose lips will you bite?

What about the similarity of the phrases used here and in [c 87] for Lesbia, 'loved by us as never a girl will ever be loved'? Well, that can easily be interpreted as a formula Catullus kept in his poetic toolbox for use on occasions when some girl or other flounced out on him.

All this extended ratiocination will have convinced the reader of one thing only: the author has no idea what to do with [c 8]. Is it even a Lesbia poem? No idea. We shall just leave it here, plastered with warning stickers.

Love and hate

Three short poems appear to follow the moment of breakup: [c 72], [c 85] and [c 75]. In these Catullus examines the paradox of his increasing hate and simultaneously increasing desire for Lesbia.

The three poems hang together so closely that their precise sequence is more or less irrelevant. If only from the different tenses used we can take [c 72] as following [c 70], a sequence which accords closely with the narrative progress of the breakup. [c 85] could come anywhere in this sequence.

C 72: loss of respect but growing passion

Once you used to say you knew only Catullus, Lesbia, that you would not hold Jove before me. I loved you then, not only as a fellow his mistress, but as a father loves his own sons and sons-in-law. Now I do know you: so if I burn at greater cost, you are nevertheless to me far viler and of lighter thought. How can this be? you ask. Because such wrongs drive a lover to love the more, but less to respect.

Dicebas quondam solum te nosse Catullum, / Lesbia, nec prae me velle tenere Iovem. / dilexi tum te non tantum ut vulgus amicam, / sed pater ut gnatos diligit et generos. / nunc te cognovi: quare etsi impensius uror, / multo mi tamen es vilior et levior. / qui potis est? inquis. quod amantem iniuria talis / cogit amare magis, sed bene velle minus.

[c 72]

After the disaster of the separation, Catullus once again spends some time trying to depict the special nature of their relationship. When we read that Catullus loved Lesbia not only as a man loves his mistress, but 'as a father loves his own sons and sons-in-law', we unavoidably think back to the philosophising in [c 109] and [c 87]. The present three poems should be read as an extension of those two.

The elevation of the spiritual quality of that relationship with Lesbia – love, holy friendship and faithfulness – has been so great that the fall, now it has finally come, is precipitous.

[c 72] also opens another theme: that not only can Catullus not stop loving Lesbia despite all the injuries she is inflicting on him, but that these injuries even increase that love. All the courtly and metaphysical components of their relationship seem to have disappeared to leave only mindless lust behind.

The love-hate theme is restated laconically in [c 85], where Catullus seems to be as puzzled as we are at the paradox he is living through:

C 85: the paradox of love and hate

I hate and I love. Why I do this, perhaps you ask. I know not, but I feel it happening and I am tortured.

Odi et amo. quare id faciam fortasse requiris / nescio, sed fieri sentio et excrucior.

[c 85]

The modern psychologist would infer that the torture Catullus is experiencing arises from a deep cognitive dissonance between his simultaneous feelings of contempt and passion for the same woman.

He has invested so much emotional and intellectual capital in Lesbia that the bankruptcy is extremely painful. Even more painful is the awareness that his deep feelings for her were, from the beginning, totally misguided.

The bankrupt – whether financial or emotional – looks back from the pain of the moment and experiences the deeper pain caused by the sudden self-awareness of his own failings and his own gullibility. All the hopes which he had are suddenly perceived as delusions.

Yet, despite this new intellectual awareness of her defects and his own failings, his lust for Lesbia is still present, which results in the ultimate torture: the contempt he feels for himself at his continued lusting after her.

The next poem in our series, [c 75], continues and extends this theme:

C 75: more hatred and more love

Now is my mind brought down to this point, my Lesbia, by your fault, and has so lost itself by its devotion, that now it cannot wish you well, were you to become most perfect, nor can it cease to love you, whatever you do.

Huc est mens deducta tua, mea Lesbia, culpa, / atque ita se officio perdidit ipsa suo, / ut iam nec bene velle queat tibi, si optuma fias, / nec desistere amare, omnia si facias.

[c 75]

Once again Catullus struggles with the paradox of the injury and betrayal that can never be forgiven which is simultaneously coupled with the amare, 'sexual desire', that is only intensified. We noted how dampened and chastely reported that part of the relationship was at the beginning – kisses merely – while the cerebral and emotional parts of the relationship expanded. Now the latter have been destroyed by the latest betrayal, the heightened sexual attraction remains.

As we noticed when we were considering the seminal [c 109] and [c 87], in which we found Catullus exploring the modalities of a (for the Roman world) completely new character of love, it's the short poems which seem to carry the largest intellectually and emotionally explosive payload.

[c 75] makes it clear that Lesbia's 'fault', her faithlessness, has caused a complete collapse in the trust that Catullus has so unwisely placed in her. But what do we make of the single, quite remarkable phrase atque ita se officio perdidit ipsa suo, 'has so lost itself by its devotion'? What on earth can this mean?

It appears to be the justification Catullus needs to explain his juvenile loss of mental balance in his affair with Lesbia – his 'devotion' was simply too strong. We sensed that devotion in the long tussle he had to find some fitting Latin terminology to express his feelings properly. A remnant of that devotion still animates his love, which will masochistically still persist whatever injuries she may inflict upon him: 'whatever you do'.

The poetry of self-loathing

This series of three brief poems [c 72], [c 85] and [c 75] have marked out the triangle of Catullus' sufferings at the loss of Lesbia and briefly delineated their emotional components: embarrassment at his own gullibility, self-hatred for his continuing and even intensifying sexual desire for Lesbia; hurt at her flagrant violation of his trust.

Copley also took these three poems as a group and carried out a detailed linguistic and psychological analyis on them, concluding that:

In so doing, his heart has 'destroyed itself'; the poet’s concepts of right and wrong are in confusion, and he is caught up in a situation in which willy-nilly he is pursuing a course which he knows is wrong. It is this feeling of guilt, of wrong-doing, which gives the poem its tragic overtones. Catullus is not merely frustrated or stubborn; he is afflicted by a realization that he has not been true to his own ideal. It is not only that Lesbia has not been true to him: he has not been true to himself. Yet he persists in his course; he goes on desiring her when he knows he should not; he is now even convinced that he can never cease to desire her. This is the guilt which oppresses him and throws him into despair.

Copley p. 90f.

Particularly [c 85], in its brevity and undecorated bleakness, is a cry from the heart from one without comprehension:

For that matter, Catullus himself does not understand why he suffers so — witness the despairing nescio which he offers in reply. He senses only that he is possessed at once by two emotions which he knows, perhaps only by a sort of cloudy intuition, ought to be mutually exclusive. The modern, backed by his tradition of romantic love, can understand Catullus better than could the poet himself, for it is now commonly accepted, at least as an ideal, that desire is right only if it is accompanied by love — using the word again in its modern sense. Unaccompanied by spiritual and intellectual sympathy, physical desire is, if not morally wrong, at least unworthy or improper. Whatever may be modern practice in this respect, the accepted moral code condemns such unrelieved animal feelings, and our ideal of love assumes the justice of this condemnation. Catullus, alone of the ancient erotic poets, has a prevision of this ideal, and c. 85 shows that he was scarcely the happier for his deviation from the norm of his times. The modern, at least, could understand the reason for his sense of wrong-doing; Catullus senses only the wrong-doing; the reason is beyond his grasp. To be conscious of doing wrong, but not to know why the wrong is wrong — this is indeed excruciari.

Copley p. 92.

Frank Copley wrote this at the end of the nineteen-forties. He could assume his readers understood the link between desire and love. But it was written just on the threshold to the next half-century, a period which would 'liberate' everyone, detach sex from love and guilt from sex, introduce the 'zipless fuck' (= the 'one-night stand' for women), performance without passion and many more Graeco-Roman habits. Will any modern reading this still understand Catullus' distress?

Before we move on to trace out the remainder of the arc of this love affair let us make one further assertion. Anyone who wishes to understand the Lesbia poems has to establish a convincing interpretation of this tripod of poems [c 72], [c 85] and [c 75] – and also [c 109] and [c 87], while they are about it. They are all short, but as we have already noted, they carry the largest intellectually and emotionally explosive payload .

From now on, the relationship with Lesbia plunges steeply downhill for Catullus.

The great tirade

Having poked into the depth of feelings swirling in Catullus' head, we are now in a position to understand the cause of the storms of hurt and invective that lie ahead.

The most hurtful of them was the lack of fides, fidelity, for Lesbia seemingly betrayed her lovelorn poet. Our cynics – a rough crowd – find all this discussion of fidelity carried on in the middle of an adulterous relationship worthy of scorn, but passionate poets tick like everyone else when temptation beckons.

C 11: invective against Lesbia

Furius and Aurelius, comrades of Catullus, whether he forces his way to furthest India where the shore is lashed by the far-echoing waves of the Dawn, or whether to the land of the Hyrcanians or soft Arabs, or whether to the land of the Sacians or quiver-bearing Parthians, or where the seven-mouthed Nile colors the sea, or whether he traverses the lofty Alps, gazing at the monuments of mighty Caesar, the Gallic Rhine, the shuddering water and remotest Britons, prepared to attempt all these things at once, whatever the will of the heavenly gods may bear, — repeat to my girl a few words, though they are not at all good. May she live and flourish with her fornicators, and may she hold three hundred at once in her embrace, loving not one in truth, but bursting again and again the guts of all: nor may she look back upon my love as before, which by her lapse has fallen, just as a flower on the meadow's edge, after the touch of the passing plough.

Furi et Aureli, comites Catulli, / sive in extremos penetrabit Indos, / litus ut longe resonante Eoa / tunditur unda, // sive in Hyrcanos Arabasve molles, / seu Sacas sagittiferosve Parthos, / sive quae septemgeminus colorat / aequora Nilus, // sive trans altas gradietur Alpes / Caesaris visens monimenta magni, / Gallicum Rhenum, horribile aequor, ulti- / mosque Britannos, // omnia haec, quaecumque feret voluntas / caelitum, temptare simul parati, / pauca nuntiate meae puellae / non bona dicta. // cum suis vivat valeatque moechis, / quos simul complexa tenet trecentos, / nullum amans vere, sed identidem omnium / ilia rumpens; // nec meum respectet, ut ante, amorem, / qui illius culpa cecidit velut prati / ultimi flos, praetereunte postquam / tactus aratro est.

[c 11]

Here we have yet another Lesbia-poem that does not name her explicitly. We can confidently ascribe it to the collection, though, if only because of the level of invective it contains. It is one of the only two poems which address their invective directly at her; the other is [c 58].

The use of the formulaic 'my girl' suggests that the break with her was recent: she may have dumped him, but Catullus still feels some sense of proprietorship.

The poem is in the form of an ode written in Sapphic metre. This formality alone is striking. The first four stanzas are a parody of the bombastic odes of the time. Much carbon dioxide has been emitted by commentators – whether from candles, gas lights, filament bulbs or LED devices – in the identification of Furius and Aurelius (still essentially unidentified) and the explication of the boastful and fully fictitious journeys which Catullus never made.

Merrill believes the two 'comrades' have brought a message from Lesbia offering a reconciliation and that [c 11] is Catullus' vicious response. He may well be right on this point, since the poem, apart from the complex metre, follows a formula common in heroic poetry for the rejection of the offer brought by a messenger: what one Homeric scholar [whose name escapes me] once called 'the formal boasting of the Achean warrior'. After making the messengers stand there and listen to this, they are then sent back with an appropriately crafted and insulting rejection.

The rejection itself comprises two stanzas. The first of these is so obscene that it will give all visiting search engines a fright. The second stanza is, in contrast, a sublime metaphor: his love savagely and irrevocably cut down by the unfeeling and brutal plough at the meadow's edge. The man can write.

[c 11] is therefore a poem containing three contrasting sections: the parody of heroic boasting in the first four stanzas, the obscene imprecation of the fifth and the finality of the injury she inflicted upon him in the sixth. The first section inflates Catullus to Olympian proportions; the second degrades Lesbia to a sex fiend who nullum amans vere 'loves no one truly', repeating the theme of betrayed love we have discussed at length; the third section underlines the finality of the decision – there can be no way back.

Those who had to flutter their fans at the profanities in the last poem should prepare themselves for the worst – a stiff brandy may assist – as we slither into the turbid pond that is [c 37].

C 37: invective against Lesbia's many lovers

Tavern of lust and you, its tentmates (at the ninth pillar from the Cap-donned Brothers), do you think that you alone have mentules, that it is allowed to you alone to have sex with whatever may be feminine, and to think the rest are goats? But, because you sit, tasteless, hundred or maybe two hundred in a row, do you think I would not dare to bone you entire two hundred loungers at once! Just think it! for I'll scrawl dirty pictures all over the front of your tavern. For my girl, who has fled from my embrace, she whom I loved as none will be loved, for whom I fought fierce fights, has seated herself here. All of you, good men and rich, and also (O cursed shame) all of you piddling back-alley fornicators, are making love to her; and you above all, Egnatius, one of the long-haired race, the son of Celtiberia full of rabbits, whose quality is stamped by dense-grown beard, and teeth scrubbed with Spanish urine.

Salax taberna vosque contubernales, / a pilleatis nona fratribus pila, / solis putatis esse mentulas vobis, / solis licere quidquid est puellarum / confutuere et putare ceteros hircos? / an, continenter quod sedetis insulsi / centum an ducenti, non putatis ausurum / me una ducentos irrumare sessores? / atqui putate: namque totius vobis / frontem tabernae sopionibus scribam. / puella nam mi, quae meo sinu fugit, / amata tantum quantum amabitur nulla, / pro qua mihi sunt magna bella pugnata, / consedit istic. hanc boni beatique / omnes amatis, et quidem, quod indignum est, / omnes pusilli et semitarii moechi: tu praeter omnes une de capillatis, / cuniculosae Celtiberiae fili, / Egnati, opaca quem bonum facit barba / et dens Hibera defricatus urina.

[c 37]

Note: The allusion a pilleatis nona fratribus pila, 'at the ninth pillar from the Cap-donned Brothers' refers to the temple of the twin deities Castor and Pollux which stood on the southern side of the Forum. The particular house of ill repute to which Catullus refers is located at the ninth pillar counting from that temple.

One more Lesbia poem that doesn't mention her name. It would, however, be perverse not to see her role in this poem: the expression in line 11 amata tantum quantum amabitur nulla, 'she whom I loved as none will be loved' recalls [c 8.5], amata nobis quantum amabitur nulla, 'loved by us as never a girl will ever be loved'. Since she is also here described as the puella nam mi, quae meo sinu fugit, 'my girl, who has fled from my embrace', it seems to be more than likely that the girl in question is in fact Lesbia.

A particularly interesting aspect of this poem is that not only is Lesbia not mentioned by name, she is not the principal target for Catullus' vituperation. All the invective of this poem is directed at the men who use and abuse her, the bees around the honeypot, as it were, and above all a certain Egnatius – about whom we know nothing. He must have done something to annoy Catullus, since he is also the exclusive target of the invective in [c 39]. Since that poem has nothing to do with Lesbia we can leave it alone with good heart.

In the next poem of invective, [c 58], Catullus directs his venom at Lesbia in person. It is only one of the two poems we have in which Lesbia is criticised directly, the other is [c 11]. All the other poems of invective are directed at Catullus' rivals for Lesbia's ministrations.

C 58: invective against Lesbia

0 Caelius, our Lesbia, that Lesbia, the self-same Lesbia whom Catullus loved more than himself and all his own, now at the cross-roads and in the alleyways husks off the high-spirited descendants of Remus.

Caeli, Lesbia nostra, Lesbia illa, / illa Lesbia, quam Catullus unam / plus quam se atque suos amavit omnes, / nunc in quadriviis et angiportis / glubit magnanimi Remi nepotes.

[c 58]

Who was the Caelius to whom this poem is addressed? No idea.

In his commentary (1893) Merrill asserts (with some 'probably' and 'suggesting') that this person is the orator Marcus Caelius Rufus (82 BC-??), made famous by Cicero's defence of him. He then goes on to treat this supposition as an established fact.

In contrast, Robinson Ellis, in his commentary, boldly asserts that 'the Caelius of C, and probably of LVIII, was a Veronese, and cannot have been the orator'. To my knowledge no recent scholar has resolved this lacuna in our understanding, but no matter – knowing or not knowing the identity of Caelius makes no difference to us whatsoever.

Our real – slightly prurient – focus in this poem is on the image of the lovely Lesbia, pleasuring men presumably – the passing trade – in public places. Generations of scholars have struggled with glubit, the third person singular present of glubo, to peel off (like bark), or to rob or, in this poem alone, to jerk off or… whatever.

That we write 'in this poem alone' should ring alarm bells for the reader, for the copyists who have got us here wrote Glubit [G and O], Glulit, Glusit, Cludit and all stations in between, betrayed by their imprecise grasp of Latin.

Thus the details of exactly what Lesbia was doing to Roman gentlemen in dark alleyways and to whom Catullus is reporting this activity are unimportant. It is not inconceivable, that if he wrote more in this vein, particularly in less obscure Latin, monkish sensibilities may have hindered their copying and transmission. Who knows?

C 79: invective against Lesbius

Lesbius is handsome: why not so? whom Lesbia prefers to you, Catullus, and to your whole family. Yet this handsome one can sell Catullus and his family if he can find three acquaintances he can gain greet with a kiss.

Lesbius est pulcher: quid ni? quem Lesbia malit / quam te cum tota gente, Catulle, tua. / sed tamen hic pulcher vendat cum gente Catullum, / si tria notorum savia reppererit.

[c 79]

In the last line, following ms. O, Merrill reads notorum, 'acquaintances'. Ellis, however, follows G and R to read natorum 'children/descendants', devoting a lengthy excursus to the topic. Looking up some of the other readings threatens a fast track entry into the nearest psychiatric clinic: amatorum, amicorum, Fatorum, aratorum, potorum and nostrorum.

Clodia

A tradition has become established among scholars, that if Lesbia is presumed to be a certain Clodia, then Lesbius could be her brother Publius Clodius Pulcher (93 BC-53? BC), which might then mean that Catullus was alluding to the trial in 62 BC of Clodius for incest with his sister. Clodius was acquitted by (it is said) bribing the jury. He eventually came to a bad end on the swords of his enemies.

The use of pulcher, 'handsome' seems to be a heavy hint. [c 79] seems to be telling us that the stain of that incest – and some other high jinks – left Clodius untouchable in Roman society, in which case Lesbia/Clodia's continued association with her beautiful but tainted brother shows just what an immoral hussy she really is.

Catullus is willing to wager his own and his family's property (='bet the farm') on the fact of Clodius' status as a social pariah and that the shameless Clodia will continue to kiss the lips everyone else shuns.

Our salacious imagination, which already made the suggestion (based on no evidence whatsoever) that Catullus' early death may have been a case of poisoning by Clodia to rid herself of this venomous poet who circulated vulgar invective about her character, is tickled by the fact that Clodia was suspected of poisoning her husband and accused others of trying to poison her.

We cannot dive more deeply into this identification of Lesbia as Clodia – the reader's patience and forebearing has been strained enough. Much ink has been spilled on the subject by learnèd people. We simply note that the identification is not as conclusive as this convenient reading of [c 79] might suggest. Some commentators argue confidently for Lesbia/Clodia, some equally confidently against. Worse: the confident identification then generates a circular logic: philologists identify Lesbia using 'historical' sources, which then turn out to be historians relying on the philologists' identification of Lesbia/Clodia in Catullus.

The cynics among our readers might suggest that the principal attraction of linking Lesbia to Clodia is that it associates Lesbia with a relatively well documented, scandalous circle of powerful Romans, giving commentators much to gossip about.

Gellius

In the Catullan canon there is a series of seven poems [cc 74, 80, 88, 89, 90, 91, 116], which seem to belong together – their chronological order is uncertain but they are certainly linked thematically, because they all deal with someone called Gellius. Only [c 91] has any connection with Lesbia, so only that poem is discussed in detail here.

Put briefly, [c 91] attacks Gellius for being a rival lover of Lesbia. We saw in some of the other poems of invective concerning Lesbia that Catullus almost always directs his hatred against the men who engage in sexual acts with her, rather than the woman herself.

Readers who stick to the conventional sequence of the Catullus canon might get the impression that Catullus began a feud with Gellius over his incestuous conduct in [c 74] and Catullus' hatred peaked when, in [c 91], the polluted one even has the affrontery to bed 'his girl'.

However, if we free our minds of the influence of the near-random sequence of the collection, a much more illuminating sequence is possible if we take [c 91] as marking the starting point of Catullus' campaign of vitriol against poor Gellius. It was Gellius' dalliance with Lesbia which set him up as a worthy target in the first place.

C 91: invective against Gellius

For no other reason, Gellius, did I hope for your faith to me in this our unhappy, this our desperate love, not because I knew you well or thought you constant or able to restrain your mind from a shameless act), but because I saw this girl whose love kept gnawing at me was neither your mother nor your sister. And although I have had many mutual dealings with you, I did not believe this case to be enough cause for you. You considered it enough: so great is your joy in every kind of wrongdoing in which there is some vice.

Non ideo, Gelli, sperabam te mihi fidum / in misero hoc nostro, hoc perdito amore fore / quod te cognossem bene constantemve putarem / aut posse a turpi mentem inhibere probro, / sed neque quod matrem nec germanam esse videbam / hanc tibi cuius me magnus edebat amor; / et quamvis tecum multo coniungerer usu, / non satis id causae credideram esse tibi. / tu satis id duxti: tantum tibi gaudium in omni / culpa est in quacumque est aliquid sceleris.

[c 91]

From this poem we learn that Catullus considered Gellius a friend. Gellius has now insulted Catullus by bedding Lesbia, so is now in Catullus' poetic crosshairs. The focus of the attack is Gellius' supposed incestuous relationships with his mother and his sister.

If the accusations are true, this behaviour must have been going on before Gellius became entangled in Lesbia's arms. During that period, Catullus found the incest to be something about his friend that was not worth mentioning. However, once Gellius made his move on Lesbia, Catullus suddenly found the immorality of Gellius' incestuous tendencies definitely worth mentioning.

Catullus tells us that he had many dealings with Gellius in the past, but had never suspected him of such perfidy with Lesbia. Now Gellius has crossed that barrier, the general predeliction for vice by his defective character is a useful stick to beat him with.

Invective a proof of love

The following two poems, [c 83 and 92], can be assigned chronologically roughly to the period of the separation between Catullus and Lesbia, but are impossible to locate in that sequence with more precision.

They do, however, share a theme which allows us to bring them together: the notion that the intemperate behaviour of both lovers is a sign that they still love each other in reality:

C 83: Lesbia's anger the proof of love

Lesbia in her husband's presence says the utmost ill about me: this gives the fool the greatest pleasure. Mule, you perceive nothing! If she had forgotten about us and were silent, she would be all right: now because she snarls and scolds, not only does she remember, but, what is far more to the point, she is angry. That is, she is enflamed and is speaking.

Lesbia mi praesente viro mala plurima dicit: / haec illi fatuo maxima laetitia est. / mule, nihil sentis. si nostri oblita taceret, / sana esset: nunc quod gannit et obloquitur, / non solum meminit, sed, quae multo acrior est res, / irata est: hoc est, uritur et loquitur.

[c 83]

The first instance of this theme comes when Catullus tells us that Lesbia speaks badly of him to her husband – behaviour that will not surprise students of the human heart. Nor will the fact that the once-cuckolded husband laps up his wife's disingenuity surprise anyone either.

Catullus expresses his contempt for the husband's stupidity in believing his wife – which is a bit rich coming from the poet who praised faithfulness in matters of the heart so highly. Catullus interprets the fact that she hasn't forgotten him as somehow making their relationship special – or, at least, memorable. In Catullus' mind her anger shows how much he means to her. Grasping at straws, we might think.

C 92: anger the sign of love for both

Lesbia forever speaks ill of me nor is ever silent about me: I'll be damned if Lesbia doesn't love me! By what sign? because mine are just the same: I execrate her constantly, yet may I be damned if I do not love her in sober truth.

Lesbia mi dicit semper male nec tacet unquam / de me: Lesbia me dispeream nisi amat. / quo signo? quia sunt totidem mea: deprecor illam / adsidue, verum dispeream nisi amo.

[c 92]

This poem continues the theme from [c 83] but adds another dimension: Catullus realises that the anger that causes him to 'execrate her constantly' is also a sign that he loves her, too. The reader can probably agree that Catullus' obsessive invective against her is a sign – if we needed one – that he is still obsessively infatuated with her.

The end of hope

At some point Catullus himself begins to realise the depths of his obsession. A long poem, [c 76], now presents an extended monologue in which he tries to persuade himself to stop thinking about her and 'get on with his life', as we moderns say:

C 76: the need to move on

If there is any pleasure in a man's recalling the good deeds of the past, when he knows that he is pious and has not violated any sacred trust or abused the divinity of the gods to deceive men in any pact, great store of joys awaits you during your length of years, Catullus, from this thankless love of yours. For whatever people can say or do well for someone, such have been your sayings and your doings, and all your confidences have been squandered on a thankless mind. So then why do you torture yourself further? Why don't you strengthen your resolve and lead yourself out of this and, since the gods are unwilling, stop being miserable? It is difficult suddenly to set aside a love of long standing; it is difficult, this is true, no matter how you do it. This is your one salvation, this you must fight to the finish; you must do it, whether it is possible or impossible. O gods, if it is in you to have pity, or if ever you brought help to men in death's very extremity, look on pitiful me, and if I have lived my life with purity, snatch from me this canker and pest! Ah! like a numbness creeping through my inmost veins it has cast out every happiness from my breast. Now I no longer pray that she may love me in return, or (what is not possible) that she should become chaste: I wish but for health and to cast aside this foul disease. O gods, grant me this in return for my piety.

Si qua recordanti benefacta priora voluptas / est homini, cum se cogitat esse pium, / nec sanctam violasse fidem, nec foedere in ullo / divum ad fallendos numine abusum homines, / multa parata manent in longa aetate, Catulle, / ex hoc ingrato gaudia amore tibi. / nam quaecumque homines bene cuiquam aut dicere possunt / aut facere, haec a te dictaque factaque sunt: / omnia quae ingratae perierunt credita menti. / quare cur tu te iam amplius excrucies? / quin tu animo offirmas atque istinc teque reducis / et dis invitis desinis esse miser? / difficile est longum subito deponere amorem; / difficile est, verum hoc qua libet efficias. / una salus haec est, hoc est tibi pervincendum; / hoc facias, sive id non pote sive pote. / o di, si vestrum est misereri, aut si quibus unquam / extremam iam ipsa in morte tulistis opem, / me miserum adspicite et, si vitam puriter egi, / eripite hanc pestem perniciemque mihi! hei mihi subrepens imos ut torpor in artus / expulit ex omni pectore laetitias. / non iam illud quaero, contra ut me diligat illa, / aut, quod non potis est, esse pudica velit: / ipse valere opto et taetrum hunc deponere morbum. / o di, reddite mi hoc pro pietate mea.

[c 76]

This poem would not be out of place almost anywhere among the poems written after the breakup of the affair. However, since it is free of invective it does not really belong among the group of angry poems. In addition, it presents us with a feeling of resignation and a longing for some final release from his tortures, which would suggest that the poem belongs at the end of the turmoil that followed the breakup.

The poem itself is largely self-explanatory. We should perhaps take special note of longum amorem, the 'love of long standing', but to our inquisitiveness about how long is 'long', there is no answer. If we cannot answer with a number, we can read it as designating the relationship with Lesbia as a love affair and not as one of Catullus' rapid-turnaround liasons – with the sparrow girl in [c 2, 3], for example, or hot chick Ipsithilla in [c 32]. We can conclude from this that the arc of the love affair with Lesbia is not simply a documentary artefact – that is, seeming to be important only because we know more about it – but that it was an important period in Catullus' young life.

[c 76] is an important poem that completes the psychological profile of the wounded poet that traverses the arc of this love affair. To recapitulate:

- In the poems [c 109] and [c 87] we find Catullus struggling and failing to find a terminology that is capable of expressing the spiritural nature of his love for Lesbia.

- In the poems [c 72], [c 85] and [c 75] we find Catullus struggling and failing to understand and cope with his complex of feelings at losing her. We concluded that a major component of that complex was his self-loathing at still having feelings – and particularly sexual feelings – for someone who so violated his trust and his spiritual love, a spirituality she clearly did not share.

Now, in [c 76] we find him praying to be released from his torture at the breakup with Lesbia. But the release he wants is not simply the delivery from the pangs of lost love that we might expect from a failed affair, the conventional Chagrin d'amour dure toute la vie (although generally under a day and a half in practice). It is the release from his guilt at the moral defects of his own position.

Some readers may find the use of a term such as 'moral defects' in connection with Latin poets to be risible. But those readers should re-read this poem carefully – and particularly the last sentence, preferably several times:

O gods, if it is in you to have pity, or if ever you brought help to men in death's very extremity, look on pitiful me, and if I have lived my life with purity, snatch from me this canker and pest! Ah! like a numbness creeping through my inmost veins it has cast out every happiness from my breast. Now I no longer pray that she may love me in return, or (what is not possible) that she should become chaste: I wish but for health and to cast aside this foul disease. O gods, grant me this in return for my piety.

o di, si vestrum est misereri, aut si quibus unquam / extremam iam ipsa in morte tulistis opem, / me miserum adspicite et, si vitam puriter egi, / eripite hanc pestem perniciemque mihi! hei mihi subrepens imos ut torpor in artus / expulit ex omni pectore laetitias. / non iam illud quaero, contra ut me diligat illa, / aut, quod non potis est, esse pudica velit: / ipse valere opto et taetrum hunc deponere morbum. / o di, reddite mi hoc pro pietate mea.

[c 76]

These are the words of a man wanting to be freed from his feelings of guilt and self-loathing at still having unworthy feelings for someone who has so betrayed him. Frank Copley comments:

The poem becomes clear in meaning only if we understand that it is not from love itself that Catullus wishes release, but from the sense of wrong, of guilt, of unworthiness that has arisen from the persistence of his physical passion after his spiritual and intellectual affection has been destroyed. As his thought progresses, he thinks with ever-increasing loathing of the moral wrong of which he finds himself guilty. Starting as pestis perniciesque it is next torpor, and finally ends as taeter morbus 'foul disease', a phrase which can describe only a hideously ugly state of mind. Neither disappointment nor persistence in unrequited love could well be so described; the phrase is apt only if it denotes a sense of wrong, of obliquity, and of shame. Catullus' feeling here shows his conviction that love, to be good and right, must be composed of two mutually necessary parts, desire on the one hand and spiritual sympathy on the other.

Copley p. 39.

At the end of this poem, therefore we leave our poet praying for release from his moral misery. At this point of acceptance and resignation the most astonishing thing happens: Catullus and Lesbia are reconciled. Perhaps two of the conditions Catullus lists here, 'that she may love me in return, or (what is not possible) that she should become chaste' have been fulfilled.

A reconciliation

In the following two poems, Lesbia returns to Catullus and all is right with the world once more. Some editors (e.g. Merrill) believe that there was an hiatus in the love affair, and that [c 107] marks the end of this hiatus. Then at some point a total breakup occurs and the whole relationship between Catullus and Lesbia comes to a vicious end in the filthy invective that Catullus then hurls at her. That is:

LOVE -> HIATUS -> RECONCILIATION -> REJECTION -> INVECTIVE

There is definitely a reconciliation, but is that reconciliation a temporary one following the hiatus or does it come at the end of the turmoil, in which case did Catullus and his Lesbia live happily ever after? In other words:

LOVE -> REJECTION -> INVECTIVE -> RECONCILIATION

Or money is on the second.

C 107: the reconciliation

If ever something happens that you long for and want and is unhoped for, this is genuinely pleasing to the soul. And thus is it pleasing to us and far dearer than gold, that you have returned, Lesbia, to longing me, you have returned to me, longing and without hope, you brought yourself back to us. O day of whiter note! Who lives more happily than I alone, or who can name things greater to be wished for in this life?