Catullus and Lesbia

Posted by Richard on UTC 2019-07-16 14:01

Our degraded, emasculated and decadent age interleaves prudery and obscenity, taking and giving offence, vulgarity and twee politeness, rage and sullen apathy at every moment. It is an age in which the police patrol the public fora, on the lookout for 'hate speech'. It is an age when delicate flowers write 'sh*t', thinking that this proxy-word somehow protects them and their readers from the word they want to write. Let's have some passion and obscenity from a healthier age.

Catullus

- Who was Catullus? – A poet who wrote in Latin (so far so good).

- When was he born? – Don't know.

- When did he die? – Don't know.

- How old was he when he died? – Don't know.

- How did he die? – No idea.

- What did he look like? – No idea.

- Surely you can do better than that? – Not much.

Let's try though. If we put our minds to it we may find some straws just waiting to be grasped.

When did Catullus live?

He lived sometime in the first century BC is the best we can do.

If, reader, our best is not good enough for you then you will have to plug through the following specifics:

In dating Catullus' life we have four fixed stars: the four of his poems [cc 11, 29, 53, 113] which mention events that took place in late 55 BC or early 54 BC. He must therefore have been alive at that time.

But Saint Jerome in his Latin translation of the now-lost Greek Chronicles of Eusebius says he was thirty when he died, and gives his birth year as 87 BC and his death year, thirty years old, as 58 BC (57 BC in some manuscripts).

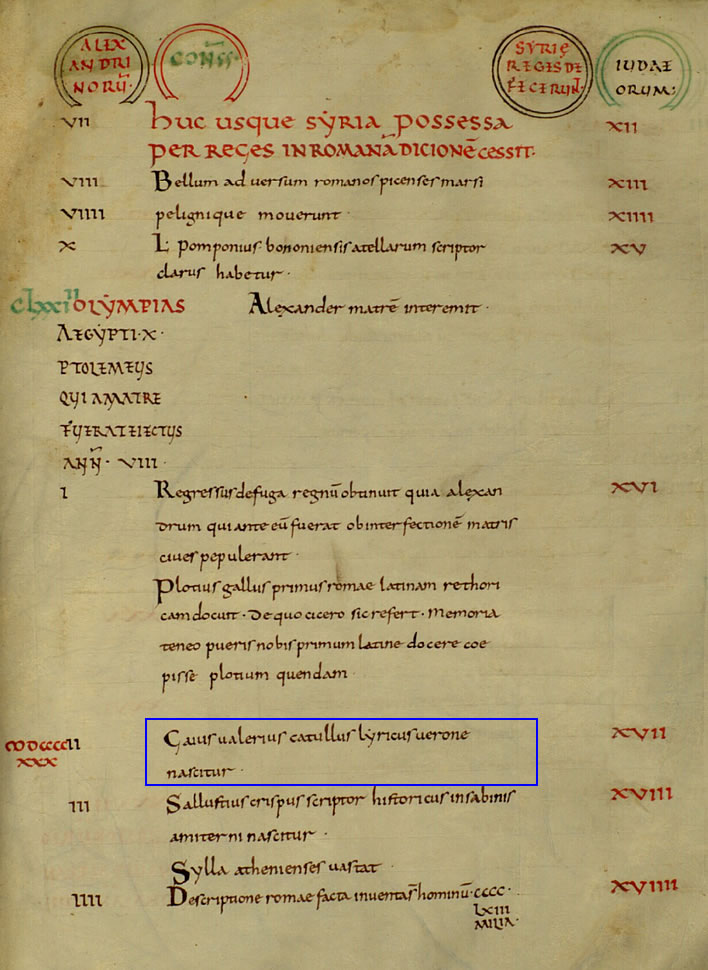

Gaius Valerius Catullus, scriptor lyricus, Veronae nascitur. 'Gaius Valerius Catullus, lyrical poet, born in Verona'. Eusebius of Caesarea, Bishop of Caesarea, (260?-340?), author / Jerome, Saint, (347?-420?), author and translator. Chronicon, Merton College MS 315. MS date: 800–1500. Folio 117r Image: Digital Bodleian.

However, from the evidence of those 'fixed star' poems, Catullus must have still been alive in 58 BC with at least three or four years to go. Thus Eusebius/Jerome's death date of 58 BC for Catullus must be wrong.

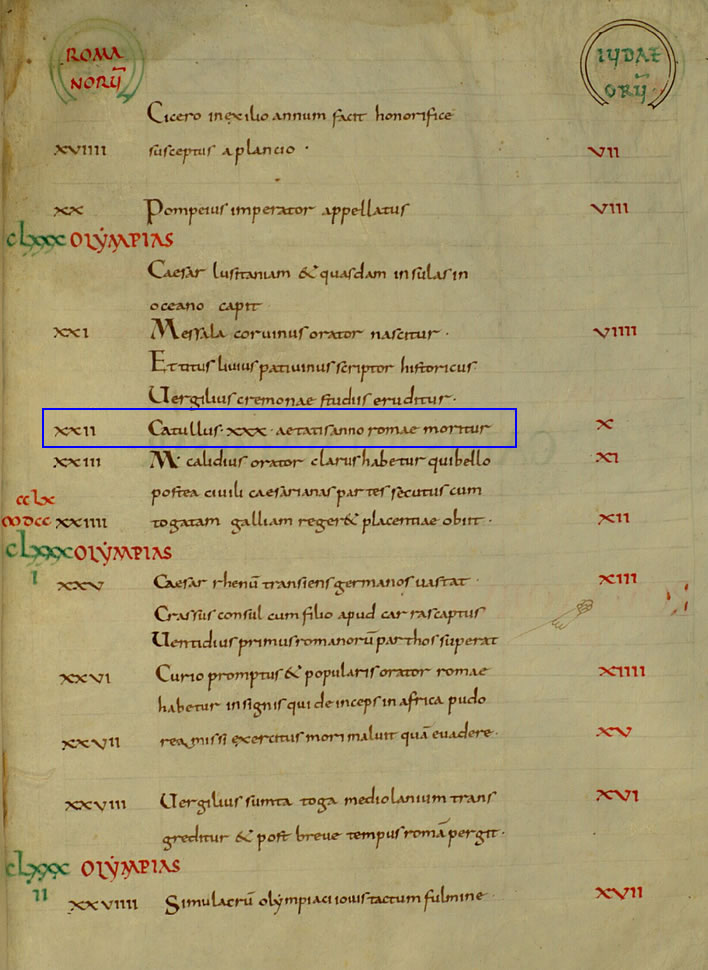

Catullus XXX aetatis suae anno Romae moritur, 'Catullus dies at Rome in the 30th year of his life'. Ibid, folio 119r. Image: Digital Bodleian.

Such errors are no surprise, since Eusebius/Jerome was, after all, writing around four centuries after the fact, centuries of turmoil and upheaval. Worse, he cites no source for this information. We have therefore no reason to believe either the birth date or the age at death supplied by Eusebius/Jerome. His observations should therefore be ignored.

Scholars down the ages, desperate to be able to write some dates for Catullus – any dates – take one or the other of Jerome's fantasies and shift the dates around a little until they encompass the fixed stars. These are all merely guesses based on no corroborating evidence whatsoever. Let's not even reproduce these dates here as though we knew them. We don't. Just writing down some date over and over again does not make it correct.

On the subject of Catullus' youthful death we are on safer ground. Ovid (43 BC-17 AD?), whose life apparently completely postdates Catullus and who is therefore not an eyewitness (though much closer than Eusebius/Jerome) tells us that 'learnèd Catullus' is in Elysium, his hedera iuvenalia cinctus, 'youthful brows wreathed in ivy' [Ovid Amores III 9.62].

The idea that Catullus died young is reasonable not just from Ovid's testimony, but from the fact that we haven't any work from him that suggests it might come from a date after 54 BC (if that was when he died). After this point there is silence from him – although that may just mean that all his later work, if there was such, has been lost. Since we find no allusions in other writers to works of the mature Catullus, the existence of some lost work from his later years currently seems less probable and a young death more probable.

The only thing we can honestly say is 'floruit first century BC and probably died young'.

Who was Catullus?

In his translation of the entry in the Chronicle for the birth of Catullus Saint Jerome writes: Gaius Valerius Catullus, scriptor lyricus, Veronae nascitur, 'Gaius Valerius Catullus, lyrical poet, born in Verona'. His full name (that is, in the Roman name structure tria nomina: praenomen-nomen-cognomen.) is also nowadays given confidently as Gaius Valerius Catullus, but even this shows more confidence than it really deserves.

Catullus refers to himself in his poetry on numerous occasions, but always simply using the cognomen Catullus. Ovid refers to him simply as Catullus, too. Some writers, following Jerome, give his nomen (gentilicium), his 'clan name', as Valerius. Some scholars give the praenomen, his 'given name' as Gaius. For a time some scholars, based on an erratic reading of one line in the poetry, thought it was Quintus.

Jerome – we say it again – was writing perhaps four hundred years after Catullus' life, so we really should be as sceptical about the names he gives us as we are about the dates. All relatively harmless, but we should always bear in mind that the only thing we are sure of is that he was called Catullus – and that is what we shall call him here.

His family came from northern Italy it seems. His birth is firmly associated with Verona: Ovid (gaudet Verona Catullo [Amores 3.15.7], 'Verona celebrates Catullus' ), Martial (debet Verona Catullo, 'Verona owes to Catullus' [Epigrammata 14.195]) and Jerome (Veronae nascitur, 'born in Verona'). One of his poems is an encomium to Sirmione, a town on a small peninsula that pokes into the southern end of Lake Garda, about 40 km to the west of Verona. It seems that Catullus or his family may have had a house there.

Sirmio, gem of all peninsulas and islands, whether Neptune sweeps round them with his wide expanse of sea or with a lake's still waters, with what pleasure, with what joy do I gaze upon you […] Hail, beauteous Sirmio, greet thy lord : rejoice, limpid waters of our lake; let all my house join in the peal of welcome.

Paene insularum, Sirmio, insularumque / ocelle, quascumque in liquentibus stagnis / marique vasto fert uterque Neptunus, / quam te libenter quamque laetus inviso, / [...] / salve, o venusta Sirmio, atque ero gaude; / gaudete vosque, o Lydiae lacus undae; / ridete, quidquid est domi cachinnorum.

[c 31.1-4, 12-14.]

He is not just a holidaymaker or just passing through Sirmione: [c 31] gives us the impression that his villa there is a place to which he gladly and often returns. Perhaps, like so many rich Romans, he escaped the suffocating Roman summer for the much pleasanter surroundings of Sirmione, the peninsula jutting into Lake Garda fanned by the cool winds from the Alps just to the north.

This is not a portrait of Catullus (in any sense that one might understand 'portrait'). This is a portrait of a some man wearing a toga and carrying a scroll. It was painted onto a wall of the large patrician Roman villa in Sirmione known since the Renaissance as the Grotte di Catullo. Catullus had been dead perhaps fifty years by the time the villa was built. It was not his villa, nor is this his 'portrait'. Catullus' paean to Sirmione, [c 31], may have led to the creation of the 'portrait', just as it led to the association of his name with the villa in the Renaissance. In more recent times the tourist business has worked its usual evil magic in the propagation of nonsense, as we noted in the case of Catullus' fake bust in Sirmione. Image: Grotte di Catullo e Museo Archeologico di Sirmione.

How much time he spent in Rome, or Sirmio or in Verona we do not know. On one occasion he writes to a younger fellow poet, Caecilius, asking him to journey from his home in the then only recently settled Novum Comum (today's Como, on the Lacus Larius, Lake Como) to join him in Verona, a journey of around 200 km, one which also passes close to Sirmione:

Paper, I would like you say to that sweet poet, my comrade, Caecilius, that he come to Verona, quitting New Comum's city-walls and Larius' shore; for I want him to receive certain thoughts from a friend of his and mine.

Poetae tenero, meo sodali / velim Caecilio, papyre, dicas, / Veronam veniat, Novi relinquens / Comi moenia Lariumque litus: / nam quasdam volo cogitationes / amici accipiat sui meique.

[c 35.1-6]

There is a reason that our muse of history, Clio, leaves her sister Erato to deal with these vague, poetic dreamers who never put dates or addresses in their work.

However, we can assume that he lived in Rome for a substantial portion of his adult life – as any Roman of any consequence had to do. He was comfortably off: his poetry suggests that his life had no major financial worries (although at one point he does complain that his purse is 'full of cobwebs' [c 13.8]).

But that really is that. We are fond of pointing out on this website that both nature and biography abhor a vacuum. In the case of Catullus the vacuum has been filled with fantasy in grand style.

A note on the texts

The Latin texts of Catullus' poems have been sourced and cited from E.T. Merrill's 1893 edition on Perseus. Merrill's Latin text and conjectures are just one of many: this source was chosen not because the text is better than any of the others, just that the website is accessible by everyone and offers a good implementation with extremely useful tools, citation aids, commentaries and translations.

Merrill's Latin has been taken over 'as is' – it has not been edited, emended or compared with other versions: doing that would have been inappropriate in the context of the current article.

Readers should be aware, though, that well over a century of meticulous scholarship has passed since Merrill's version was published. A very useful modern resource for those wishing to immerse themselves in the Latin is to be found at catullusonline.org.

The English translations used here are those of Leonard C. Smithers dating from 1894. Using this translation offers four advantages: 1) it is a good, scholarly, literal prose translation; 2) it is out of copyright; 3) the translations are available online at Perseus. Readers who look up the Merrill edition of the Latin to which we link can access Smithers' translation ('load') in a side-by-side display. Smithers bowdlerises the original to meet the needs of the sensibilities of the time, but not excessively.

An alternative might have been Charles Stuttaford's translations in The Poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus, London, Bell, 1912, now also out of copyright. Stuttaford writes a smoother, more comprehensible English, but, unfortunately, he is a mimosa who bowdlerises the original mercilessly, even to the point of leaving out the English translation of whole poems completely. The absurdity of printing Latin obscenities but not their English equivalents was clearly lost on him, but in the tenor of the times, had he translated the naughty bits, the book would never have been able to be published.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!