The Atzenbrugg enlightenment

Richard Law, UTC 2020-05-19 09:33

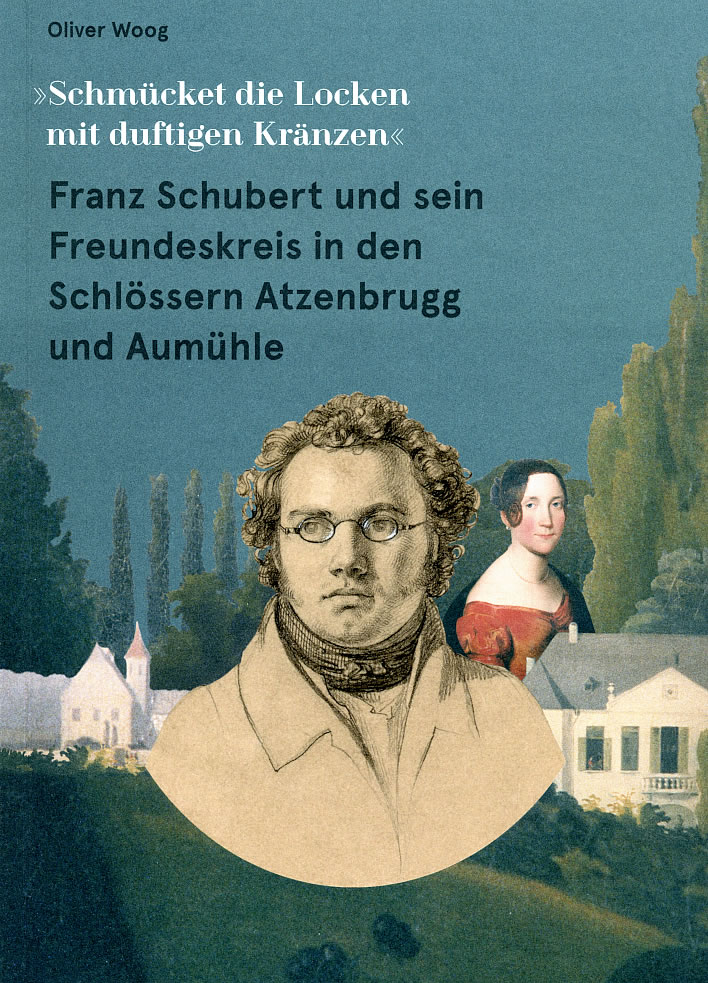

A review of Oliver Woog's book on the country house parties held in and around Atzenbrugg, made famous by their association with Franz Schubert: Franz Schubert und sein Freundeskreis in den Schlössern Atzenbrugg und Aumühle.

TEMPUS TACENDI…

This website is in the vanguard when it comes to grumbling about the deficits of the Schubert biography – mainly, that is, the documents and artefacts now mysteriously 'lost'. Then there are all the things that contemporaries chose not to write about contemporaneously and – probably even worse – all the things that contemporaries made up and wrote about forty or fifty years after Schubert had died.

Schober is the worst offender in both these respects: he was the writer and all round literary type who never bothered to write or publish a memoir of the man he knew so intimately in his young days, that superficially insignificant little man who would, in the fullness of time, become the greatest Austrian of his age. Then later, when his old friend's greatness began to emerge from the darkness which followed his death, Schober curated his fragmentary memory and his own archives into obscurity.

But instead of grumbling, let's look on the bright side for a moment. Indeed, let us kiss the ground and be thankful for the sheer fluke that the Schubert circle early on acquired two exceptionally competent artists.

Leopold Kupelwieser and Moritz von Schwind

The reader should take a moment to contemplate how empty, how desiccated the Schubert biography would be had Kupelwieser and Schwind not been around to pictorially document those times.

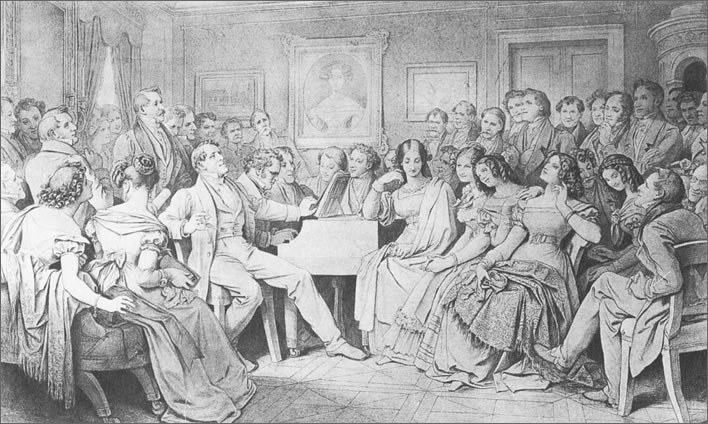

We read the fragmentary written accounts of the Schubertiaden, but it is Schwind's masterly confected reconstruction forty years after the fact that nails the concept to the door and has fixed its apparition into the mind of the average Schubert fan of today.

Moritz von Schwind's homage Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun, 'A Schubert evening at Josef von Spaun's'. Schwind avoids the Schober term Schubertiade.

We read of the social whirl of the Schubert circles, but what if we lacked Kupelwieser's sensitive, graceful and honest portraits of those involved? How bleak it would all be! He has captured those times to a greater extent than we have a right to expect of one man, has fixed for us the images of the bright young things of the age and has made the romance of that oppressed age – the frocks! the ringlets! the coats! the top hats! – has made it all manifest for us degenerates of today, who wear grubby t-shirts and go shopping in our pyjamas and whose greatest problem seems to be eating too much.

Leopold Kupelwieser (1796–1862), Gesellschaftsspiel der Schubertianer in Atzenbrugg, 1821. Drawing and watercolour. Image: Wien Museum.

Admittedly it was an age of feudal rigidity and political repression and stench and fear and short lives with unpleasant ends, but how attractive nonetheless the Age of Schubert is in our present spiritual and cultural desiccation!

In the summer of 1818 Schubert, from his first Zseliz lockdown, sent his friends a simple message from that pastoral idyll: to Vienna, to Vienna!

As happy as I am, as healthy as I am, as good as the people here are, I am looking forward again and again to the moment when I hear: To Vienna, to Vienna! Yes, beloved Vienna, you contain the dearest and the most loved in your narrow confines and only a reunion, a heavenly reunion will still this longing.

So wohl es mir geht, so gesund als ich bin, so gute Menschen als es hier gibt, so freue mich doch unendlich wieder auf den Augenblick, wo es heißen wird: Nach Wien, nach Wien! Ja, geliebtes Wien, Du schließest das Theuerste, das Liebste, in Deinen engen Raum, und nur Wiedersehen, himlisches Wiedersehen wird dieses Sehnen stillen. [Dok 64, 24 August 1818], for further context see Franz Schubert below stairs.

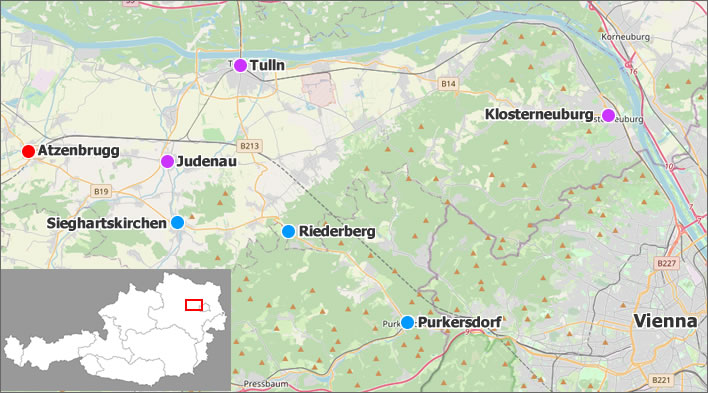

And what could represent this romantic aspect of the Schubert biography better than the three-day long summer parties the circle made in the six years from 1817 to 1823 in the country houses of Atzenbrugg and the Aumühle, roughly 40 km from Vienna.

The principal routes between Vienna and Atzenbrugg. The distance is roughly 40 km, which would be an eight hour trip in an open wagon according to Oliver Woog. The two possible routes are the St. Pölten post route via Purkersdorf, the Riederberg and Sieghartskirchen (blue) and the Danube route via Klosterneuburg, Tulln and Judenau (purple). The level agricultural area to the south of Tulln is known as the Tullnerfeld. Image: base image OpenStreetMap, localisations FoS.

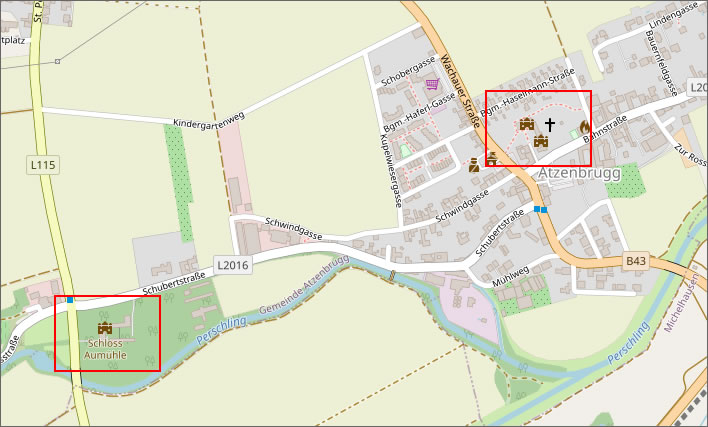

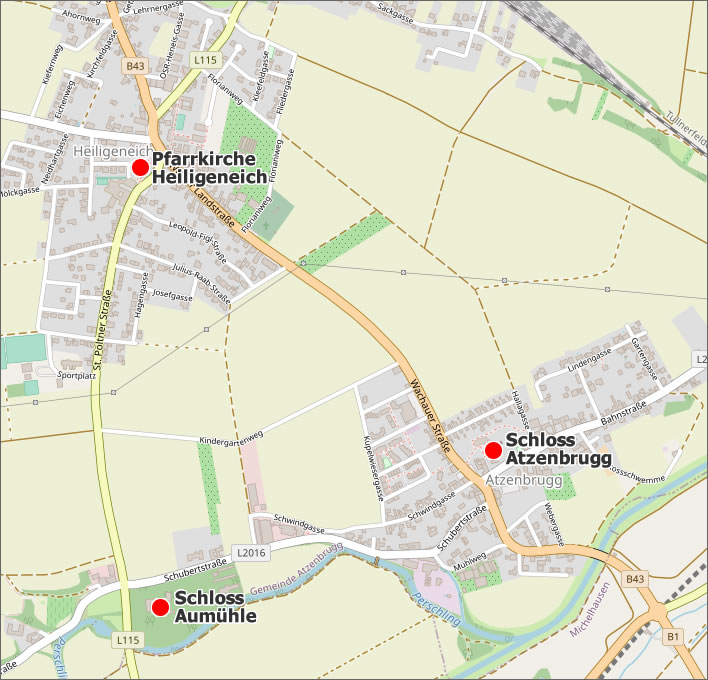

Schloss Atzenbrugg and Schloss Aumühle. Image: OpenStreetMap, localisations FoS.

The three locations discussed in Woog's book: Atzenbrugg, Heiligeneich and Aumühle. Image: OpenStreetMap, localisations FoS.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Landpartie der Schubertianer von Atzenbrugg nach Aumühl, 1820, watercolour. Image: From a lithographic print, original is in the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien.

Oliver Woog, in the prologue to his book, formulates well the significance of these summer parties for the temper of the times and our understanding of the trajectory of Schubert's life:

And anyway – is not every instance of joyfulness in Schubert's music only one side of the coin? A short while after the end of the Atzenbrugg parties Schubert became seriously ill, recovered, became sickly again and died a few years later. Some of the young partygoers died before him, among them, in 1825, Sophie Zechenter, Franz Schober's sister. Illness and political repression were constant companions. Atzenbrugg, Aumühle and Heiligeneich, however, have become symbols of carefree and innocent days in the years between the early works and the most important creative years of the composer after 1822.

Überhaupt – ist nicht jegliche »Fröhlichkeit« in Schubertscher Musik doppelbödig? Kurze Zeit nach den Atzenbrugger-Festen wurde Schubert ernsthaft krank, erholte sich, kränkelte wieder, starb wenige Jahre später. Einige der jungen »Landpartie-Teilnehmer« starben noch vor ihm, darunter im Jahr 1825 Sophie Zechenter geb. von Schober. Tod, Krankheit und politische Repression waren allgegenwärtig. Atzenbrugg, Aumühle und Heiligeneich stehen jedenfalls symbolträchtig für unbeschwerte und unschuldige Tage in den Jahren zwischen dem Frühwerk und den wichtigsten Schaffensjahren des Komponisten nach 1822.

Were it not for the illustrations done mainly by Kupelwieser but also by Schwind, this important event in the social life of the Schubert circle would be a mere footnote, leaving the Schubert biography much poorer.

And there is that man again. Once more there is no getting round him however much we dislike him: Franz von Schober.

Franz von Schober

Schober not only played an early part in the creation of one of the most famous of the illustrations of the goings-on in Atzenbrugg, Die Schubertianer beim Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg, but he was instrumental in setting up and running the parties. They were his invention, just as were the Schubertiaden, the reading circles and so much else that went on in the Schubert biography.

If we believe Schober's account of the matter, it was he who rescued Schubert from the drudgery of the life of an assistant schoolmaster under his uncomprehending, martinet father (at least as Schober portrayed him).

Die Schubertianer beim Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg c. 1820, a collaborative work by Franz von Schober, who drew the scene, Moritz von Schwind, who drew the figures, and Ludwig Mohn, who did the etching. In his book, Oliver Woog gives us a reasoned guide to the identity of the figures shown in the illustration. Images: Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Wien.

Schober was a moneyed enthusiast for hobby horses. In this respect he reminds us of Mr Toad, the moneyed enthusiast in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows (1908). Schober became the hinge around which so much of Schubert's life turned. Schober, Schober, Schober – everywhere Franz von Schober!

After Schubert's death Schober's hobby horses turned for the rest of his own long life to self important trivia of no importance at all. Schober wriggled out of the Schubert age like a creature emerging from a chrysalis, which he then left behind him seemingly without further thought.

But in that golden age among the bright young things of the circle he had had his uses: donor, enthusiast and charismatic, all-purpose gabbler. But that age scarcely lasted two decades: Schubert died young, the bright young things married and made careers in the Empire of Paperwork, and then, soon after, that evanescent world of swishing frocks and careful manners and polite young men tumbled over time's waterfall, leaving a world of Pauperismus and revolution, the rise of the Teuton and the clash of empires to come:

…

Then they left you for their pleasure: till in due time, one by one,

Some with lives that came to nothing, some with deeds as well undone,

Death stepped tacitly and took them where they never see the sun.Yes, you, like a ghostly cricket, creaking where a house was burned:

"Dust and ashes, dead and done with, Venice spent what Venice earned.

"The soul, doubtless, is immortal — where a soul can be discerned.…

"As for Venice and her people, merely born to bloom and drop,

"Here on earth they bore their fruitage, mirth and folly were the crop:

"What of soul was left, I wonder, when the kissing had to stop?"Dust and ashes!" So you creak it, and I want the heart to scold.

Dear dead women, with such hair, too — what's become of all the gold

Used to hang and brush their bosoms? I feel chilly and grown old.

Robert Browning, 'A Toccata of Galuppi's', from Men and Women, Volume 1, 1855.

For a few years in Atzenbrugg the world of the young ones was full of hope and ambition, but it didn't last. When Schober emerged newly-formed from his chrysalis after Schubert had gone (and his lithographic business had collapsed) he was merely a walking relic from those years, a sort of Ancient Mariner of the Biedermeier. Detached from Schubert's great star, Schober's inner mediocrity found its level.

But Schubert's star itself tumbled into general oblivion for forty years, so there was no one to catch the arm of this relic – this left-over half of that once legendary creature the 'Schobert' – and ask what it had been like to know the great Schubert. Some Browning, again:

Ah, did you once see Shelley plain,

And did he stop and speak to you

And did you speak to him again?

How strange it seems and new!

From Robert Browning, 'Memorabilia' from Dramatic Lyrics, 1842.

…TEMPUS LOQUENDI

What can we recover from that age?

The late Viennese musicologist and archivist Ernst Hilmar, in Franz Schubert, his popular compact Schubert biography for Rowohlt in Germany from 1997, devotes a paragraph [p. 69f] to the Atzenbrugger festivities and of course – who could resist them? – reproduces two of Kupelwieser's aquarelles on the theme.

The paragraph is a solid and scholarly piece of work that tells the reader with great economy everything – and nothing – leaving thoughtful readers wondering what that was all about.

In his useful Schubert-Lexikon, also from 1997, Hilmar devotes a column [p. 17] to much the same information, though decorated with a few cross references. These two publications represent the state of knowledge about the Atzenbrugg parties from nearly a quarter of a century ago.

Thanks to Oliver Woog's meticulous and thorough archival research now published in the present book we now know much more about these events of Schubert's young manhood and of Schober's part in them. Woog is thorough: he has not only collected together much that was scattered, but he has added significantly to the sum of our knowledge on this theme. These parties were important events in the calendar of the Schubert circle and finally we can take a detailed look at them.

The occasion for the publication of the work is the 200th anniversary of Schubert's first visit to Atzenbrugg in 1820.

The friends

As already noted, there were six annual three-day parties, from 1817 to 1823. Once we go beyond that simple fact the mythical edifice of the Schubert 'Circles of Friends' receives one more bash from the wrecker's ball: Schubert seemingly did not even attend the first three of these six events and also skipped the last one. He thus attended only one third of the series. We should therefore try to be accurate and avoid much of the later emoting and confusion caused by calling the party crowd 'Schubert's Circles of Friends'.

This was certainly a circle of friends, of that there is no doubt, but it was a circle to which he only occasionally belonged. He was just another member, albeit a talented one, available, like that other musician in the group, Gahy, to bang out some dance tunes and something more cerebral when required.

Schubert first attended the Atzenbrugg party in summer 1820. 1820? – wasn't that the year that Johann Senn was arrested? And, more accurately, wasn't that at the end of March, just a few months before that year's party?

Whilst the golden lads and girls were skipping around the Atzenbrugg lawns, Senn was sitting alone in a police prison in Vienna, tortured by hunger and beatings and subjected to interrogations whilst the authorities wondered what to do with this oddity who had even impressed their stern minds with his steadfast convictions and oratorical powers. This mistreatment would last for one year two months and ten days.

Even before the moment when Senn was released into a life-long exile, Schober, his replacement in Schubert's affections, had invented the Schubertiade, the first of which was held in January 1821. There's an exam question for you: '1812-1819 was the Age of Senn, 1820-1828 the Age of Schober. Discuss.'

'What of soul was left, I wonder, when the kissing had to stop?' We non-Austrians can only marvel at the ability of that wonderful people to flirt and have fun and carry on kissing even when the columns of the imperial temple are already trembling. Hitler somehow missed out on that Austrian gene, otherwise he would have been whirling Eva around the dismal Berlin bunker to Lanner and the Strausses.

The Modernist American poet Ezra Pound (a spook who haunts this website) might have viewed this 'circle' as one of those cultural vortices that set the innovative tone of the times. It had artists of all sorts – musicians, visual artists, writers – and in normal times something exciting might have come of it, the synergy of it all.

But these were the oppressive days of Emperor Franz II/I and his Austrian and later European belljar, so the best that could be achieved was a little innocent recreation, a little discreet flirting, lots of dancing and happy games.

If Schubert's attendance in 1820 is a bit of a puzzle, his absence in 1823 is clear: he was recovering from the early, very visible and antisocial stages of his syphilis and was consequently in no mood or state to present himself in Atzenbrugg. We recall Woog's perceptive remark of the two sides of Schubert's coin.

Why he missed the first three events is a matter for conjecture. Schober, the moving spirit of the Atzenbrugg parties had only got to know Schubert in 1815. Perhaps in 1817 Schubert was just too broke for such bourgeois frivolities. In 1818 Schubert was away for the summer in Zseliz, in 1819 he was travelling in Upper Austria in the company of Michael Vogl. In 1820 his former squeeze Therese Grob married the master baker Johann Bergmann, so there was no one to hold him back. When Schubert was not there in person, the event took place without him, as it did with many of the later Schubertiaden-without-Schubert.

Perhaps by the time of his first visit in 1820 he had freed himself enough from his Jesuitical, drudgery-obsessed upbringing to venture out to Atzenbrugg, the place where the wild things were. Who knows?

The attendees

And then there is the key question, the answer to which would allow us to start an analysis of this long gone Viennese vortex: who attended Atzenbrugg? Fortunately guests lists exist for all of the events.

Hooray! we cry, until we get a grip on ourselves and recall that this is Schubert archival research after all, a hostile universe in which all enthusiasm ultimately founders on the rocks.

In this particular case, as Woog carefully details, the lists were compiled by Max Kupelwieser, Leopold's youngest son (1845-1929). Max transcribed these lists at an unknown date from unknown sources. It appears that the transcription occurred late in Max's life, possibly around a century after the events themselves.

Many of the entries are incomprehensible. Some brave Schubert scholars have beaten their heads on their typewriters in the decipherment of some of the names on these lists. Ernst Hilmar tried it, Rita Steblin – master of reading the unreadable – cracked a few more and now Oliver Woog deserves credit for extending the list of deciphered names and adding relevant biographical information to his readings. He devotes nine pages of his book to his examination of this important subject and has gone to some lengths to establish the relevance of the suggested people. There are still question marks and it seems as though there always will be.

Beneath the surface

We may speak of the Atzenbrugg parties as a cultural vortex, but the Austrian writers of the times were a bloodless lot in comparison with many of their German fellows. Woog hints at hanky-panky at the parties, but of the glow of candlelight on the bare shoulder or the blush of a pale cheek we read nothing.

Emperor Franz II/I – the grumpy, timorous, bloodless Franz – had sucked the blood out of that generation. What little there may have been left pulsed weakly under the motto: write nothing down! Were women really nothing more than a dynastic opportunity for Biedermeier Man?

Consider that there is no love or erotic poetry worth the name during that entire period. Goethe's (1749-1832) erotic masterpiece Römische Elegien was published in mutilated form two years before Schubert was born and effectively marked the end of the sensual muse in German until Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) called it up again in the 1820s, before he had to go into exile in 1831. Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) also did his bit, but with masterful delicacy. The Romantic poets wrote of spring and moonlight and trees and spooky old castles and never seemed to notice the hot chick in front of them.

For those with an ounce of spirit left in them there was censorship, banning, career blight and prison. In almost all cases the mere threat was sufficient – the literary cavaliers of the Austrian Empire now kept their valuables well hidden. How things had changed! In England in 1642 Richard Lovelace (1617-1657), the daring and cultivated cavalier poet, had written defiantly from prison:

When love with unconfined wings

Hovers within my gates,

And my divine Althea brings

To whisper at the grates;

When I lie tangled in her hair

And fettered to her eye,

The birds that wanton in the air

Know no such liberty.

From Richard Lovelace, 'To Althea, from Prison', 1642.

The Hamburg poet Friedrich von Hagedorn (1708-1754) picked up this mood and brought it into the confidently virile rococo of his times.

But scarcely half a century later we have reached an age in which no bloodless Biedermeier cavalier could have written such stuff and if he had, no bloodless Biedermeier printer would have ever published it. True, the Unsinnsgesellschaft, the 'Nonsense Society', passed their handwritten juvenile vulgarities shiftily around amongst themselves at this time, but, if anything, that very furtiveness goes to reinforce our case.

Arguably, perhaps with the exception of Eduard Bauernfeld, Franz Schubert was the most erotic man in that circle. His physical eroticism was constrained by an unappealing body and a deeply introverted nature. In 1821 he took it for a walk on the wild side with Schober and came back with that disease that would blight him physically and mentally for the rest of his life and condemn him to a priestly celibacy.

But the reader only has to listen to his Rückert settings or the Fantasie (D 934) derived from that erotic master Rückert's Sei mir gegrüsst or the String Quintet (D 956) to realise that his mental life was quite other. Schubert was a Romantic in all senses of the word, but he was also an erotic composer.

Bauernfeld recognised this erotic drive in his friend Schubert, acknowledging respectfully, as one lover of women to another, Schubert's madly hopeless but throbbing passion for Countess Caroline Esterházy: 'I like that in him' – no dynastic cotillion here.

This erotic imagination is the reason that Schubert's settings of works such as Gretchen am Spinnrade and Nähe des Geliebten are so good – they throb with passion. As Beethoven famously said to Grillparzer: 'it's a good job the censors can't read musicians' minds'. No writer dared write what was in Schubert's mind.

Joseph Derffel

Aside from the guests of the parties, two further figures are of importance in the history of the location: Joseph Derffel (c. 1766-c. 1849-52), the manager of Schloss Atzenbrugg between 1816 and 1834 and Maximilian Joseph Gritzner (1794-1872) the owner of Schloss Aumühle.

Derffel is notable mainly for being the uncle of Franz von Schober. His sister Katharina Derffel (1762-1833) married Schober's father Franz Xaver [von] Schober (1759-1802) in 1786. Woog rightly cautions us about the confusion that exists between the various Derffels of the time. The takeaway is that Schober thus had convenient access to the albeit rather grumpy administrator of Schloss Atzenbrugg.

Derffel eventually sank under his debts and disappeared – hence the great uncertainty over the date of his death. Just to increase the confusion, a cousin of Schober's, Franz Derffel (1791-1865), was part of the group of friends around Schubert in 1826-7.

Max Joseph Gritzner

The second personality, Maximilian Joseph Gritzner, is a much more interesting figure, certainly no passive host but closely integrated in the circle.

He studied Jurisprudence at the University of Vienna between 1819 and 1822. He became part of a group of students and academics who were discontented with the repressive atmosphere of Franz II/I's increasingly autocratic rule.

The nationalist hopes that young Germany and young Austria had felt during the twenty years of the Napoleonic humiliation were squashed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 when Prince Metternich, the Austrian Foreign Minister, cobbled together a pan-European alliance that almost completely restored Europe to the despotic feudal conditions that had existed before the French Revolution had so rudely broken the autocratic calm in 1789. The hotheads had certainly not expected that outcome of the Congress.

Marx and Engels were always clear on the point: revolutions started not with the revolt of the proletariat but with the creation of a leadership caste from educated malcontents. The centres of discontent in the German-speaking countries of Europe were the Burschenschaften, slightly absurd student societies which however provided the seed around which the political resistance of students and academics coalesced and could be organized. The members of these Burschenschaften showed how easily they could be mobilised to the cause. The powers that be in the Austrian Empire and in the German states became extremely worried by these student associations.

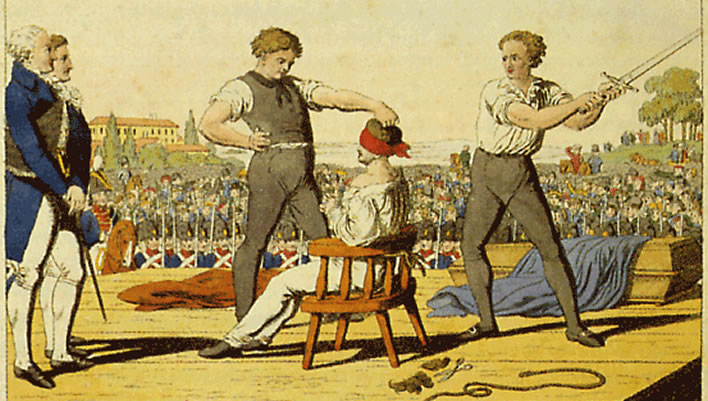

The assassination of the playwright and writer August von Kotzebue (1761-1819) on 23 March 1819 by the deranged student Carl Ludwig Sand (1795-1820) and Sand's prompt arrest and public beheading set alarm bells ringing throughout the Metternich system. The merest suspicion of conspiratorial meetings in student circles, whether formal Burschenschaften or not, was the trigger for hard repression.

The execution of Carl Ludwig Sand in Mannheim on 5 May 1820.

Max Gritzner the law student had become mixed up in the revolutionary movement in Vienna. He had become friends with Aloys Fischer, another law student from the Tyrol and through him with fellow Tyrolean Johann Chrysostomas Senn.

The young Tyroleans already had a substantial chip on their shoulders about the despicable treatment of their country by the Austrian authorities in 1809, when said authorities had betrayed the brave resistance put up by the legendary Andreas Hofer and his countrymen to the French invasion. It is one of the ironies of history that it was the Tyroleans – so loyal to their Emperor and so piously Catholic – who were comprehensively stiffed by their beloved Emperor to placate the common enemy. Napoleon put Hofer to the firing squad. His manly end made a martyr of him. The French took over the Tyrol with the connivance of Vienna.

Schubert fans – at least the ones who visit this website – know all about this period and the events that led up to the shameful arrest and the more than year-long illegal incarceration of Johann Senn. Aloys Fischer got away in an adventurous flight, Franz von Bruchmann (1798-1867), son of an important father, got a good talking to, as did Joseph Ludwig von Streinsberg (1798-1862).

Gritzner was involved in all this sedition, but to what degree we do not know. Schubert, too, was involved, though only obliquely, since was not a student. His loud resistance in the cause of his friend Senn nearly got him into trouble, however. The police raided apartments and seized diaries and journals, they were thus able to get a good picture of the network of agitators and thinkers behind the movement and snuff the incendiarists out for a generation. The Emperor wanted 'calm' – and calm is what his policemen gave him.

Senn's life was destroyed, his promise evaporated in the many privations of exile; Fischer remained an object of police interest in Tyrol; Bruchmann got religion, much to Senn's disgust; Schubert kept his head down and concentrated on his music for the eight years that were left to him; Max Gritzner completed his legal studies and gained the diplomas that qualified him as an estate administrator – scraps of paper were everything in the Empire of Paperwork. He turned his attention to these tasks and to his family and seemingly kept his revolutionary feelings to himself.

The circle of women

If Joseph Derffel, the administrator of Atzenbrugg, is of interest to us as a result of his relationship with his nephew Schober, in the case of Max Gritzner, the Aumühle owner, we note a particular friendship with Leopold Kupelwieser and his fiancée Johanna Luz.

The late Rita Steblin always maintained that a true understanding of the world of Schubert and his friends required much more attention to be paid to the females in the biography, traditionally neglected in the research.

We find another vindication of her position in the present study, in which Oliver Woog sketches the network of females friendships that link the members of the circle. Max Joseph's wife Josepha Gritzner (1798-1875) was part of a female circle of friendship that included Kupelwieser's fiancée Johanna, Schober's mother Katharina and sister Sophie, Justina Bruchmann et al. Johanna referred to this principally female web as die Gesellschaft, 'the society'.

In doing this, Woog delivers yet another argument in support of the thesis that the Schubert 'circles' that are such a staple of the Schubert literature – scholarly or general – should really be called the 'male circles', since the huge web of female connections is largely ignored and unknown.

Any man who thinks these females unimportant should think again. Perhaps a glance at Moritz von Schwind's little-known painting Gesellschaftsspiel, which Oliver Woog reproduces, will clarify one aspect of the meaning of Gesellschaft. The painting is as much constructed artifice as Schwind's 'Schubert Evening', but even more revealing because of that.

Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871), Gesellschaftsspiel, post 1860. Image: Museum Belvedere, Wien. [Click to see a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Behind the dashing female figures there are four men. One is certainly Schober, the others remain unidentified. My guess would be Max Gritzner (and wife?) and Leopold Kupelwieser (next to Johanna?). The scene seems to be set at the Aumühle and those four figures would frame the event nicely. But, who knows?

The men in Schwind's Gesellschaftsspiel. Top left: Leopold Kupelwieser(?) and Johanna Lutz(?). Top right: unknown. Bottom left: unknown, Kupelwieser might also be a possible. Bottom right: Franz von Schober. Image: Sammlung Museum Belvedere / FoS.

Unlike Schwind's 'Schubert Evening' reconstruction, the faces of those involved are only loosely delineated. The painting is almost sketchwork, intended to capture the movement of the women and the flow of their dresses – which it does very well. Whereas Schwind's homage Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun is precisely titled, the Gesellschaftsspiel couldn't be more vague.

1848, a fork in the road

But back to Max Joseph Gritzner and Oliver Woog's interesting account of this fascinating man, for Gritzner's life of turmoil has barely begun.

Gritzner gained further qualifications and moved steadily through the Austrian Empire's extensive bureaucracy. Whereas many others in the Schubert tribes could buckle down into such roles in order reliably to put food on the table, Gritzner had a restive and contrarian nature, as we might have gathered from his student activism.

In his thirties and forties he skipped from public post to private job, effectively separated from his wife Josepha with whom he had, it seems, a difficult relationship. At the beginning of his fifties he finally landed a senior position: Hofsekretär beim General-Rechnungs-Direktorium. The Empire of Paperwork was also the Empire of Job Titles: even if we could translate this in some way into English, it would mean nothing to the modern reader. It meant a bit of status.

That was in 1847, leaving him with around one year of status until the simmering revolutionary movements in Europe broke the surface calm in 1848, the great revolutionary year. Gritzner's sense of democracy and social justice, which seems to have slumbered or been repressed during his careerist days (in which a firmly closed mouth and an empty mind was essential) was awakened.

He involved himself in politics: he represented the Austrian state of Carinthia as a member of the Frankfurt National Assembly, the revolutionary body that would preside over the new order. In the October uprising in Vienna he served as a colonel in the revolutionary forces.

But the bubbling revolutionary pot in Europe was soon taken from the flame and the lid put firmly back on. When the uprising was put down he found himself on the wrong side. His son Max Carl – a hothead like his father – even ended up a wanted man who would have been executed had he been caught. Both of them fled independently to the USA.

For roughly the decade of the 1850s Max and his son established themselves in the new land – they both seem to have had that get-up-and go spirit that became associated with American success. But by the beginning of the 1860s both of them were back in Europe. The amnesty for their doings in the revolutionary times was issued in 1867. The five years of life that remained to Max Joseph were spent in restless activity, just as the previous seventy years had been.

The Schubert archival curse strikes once more though. Oliver Woog notes that the autobiography this remarkable man wrote skates over his student years in Vienna – just those years that would interest us most – and that his correspondence from the years before the 1848 revolution has been lost. The latter is not really a surprise, given the personal upsets of revolution, flight and exile that followed, but just one more known unknown to add to all the others, not to mention the unknown unknowns.

Woog's book contains a charming two-page surprise for the reader: the personal recollections of Renate Welsh-Rabady, the great-great-grandaughter of Max Joseph Gritzner, who inherited Gritzner's letters and autobiographical memoir. She describes how she came by them and how this eventuality unfolded into reading and learning about her ancestor Max Joseph's restless life. The memoir illuminates the mystery of archival research, in that so often someone, somewhere – in a shoebox, a drawer or an attic – has one or more pieces of a puzzle that are capable of throwing new light on an age.

Oliver Woog disentangles many other strands of the Gritzner story concerning relatives and children. He deserves praise for the fact that the storytelling is firmly anchored and documented in archival research. Those reading the story may skip the documentary citations and excursions but Woog has done a service to Schubert research by citing his sources.

This book is a very welcome contribution to Schubert scholarship. This reviewer will have to revise some of his own previous statements in the light of this new information. This review has barely scratched the surface of Woog's contribution. Anyone interested in the Schubert biography will need to have this work on this important Atzenbrugg period to hand. Even those who may struggle with German will find Woog's writing clear and easy to decode – unlike those damn guest lists, of course.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!