Goethe's Römische Elegien I-IV

Posted by Richard on UTC 2020-10-21 06:42

I Prolog [n3]

Hier ist mein Garten bestellt, hier wart ich die Blumen der Liebe,

1Wie sie die Muse gewählt, weislich in Beete verteilt.

Früchte bringenden Zweig, die goldenen Früchte des Lebens,

3Glücklich pflanzt ich sie an, warte mit Freuden sie nun.

Stehe du hier an der Seite, Priap! ich habe von Dieben

5Nichts zu befürchten und frei pflück und genieße wer mag.

Nur bemerke die Heuchler, entnervte, verschämte Verbrecher;

7Nahet sich einer und blinzt über den zierlichen Raum,

Ekelt an Früchten der reinen Natur, so straf ihn von hinten

9Mit dem Pfahle, der dir rot von den Hüften entspringt.

Here have I laid out my garden, here I tend the flowers of love, as the muse has chosen them, wisely planted around the bed.

Branches that will bring forth fruits, the golden fruits of life, happily I plant them, wait with pleasure for them now.

Stand here at the side, Priapus! I have nothing to fear from thieves, and those who will may pluck and enjoy as they wish.

But spy out the hypocrites, enervated, prudish criminals; should one of them approach and squint at the delicate assembly,

revulsed by the fruits of pure Nature, so punish him from behind with the pole that juts red from your loins.

Notes

weislich in Beete verteilt: Carefully arranged by G.'s poetic skill.

Priap: Priapus, the permanently aroused god with a member to die for – but you knew that already, didn't you? Naturally associated with fertility, statues to him were everywhere; the garden gnomes of the classical world. See the additional information in the Commentary.

frei pflück und genieße wer mag: Unlike the hoarded worldling's treasure, the pleasures of love are free to all to enjoy.

Früchten der reinen Natur: Fruits which are the product of 'pure Nature' not human artifice. An expression of the 18th-century idea of Nature as being in itself a pure good that only humans desecrate; a silly feeling which is still with us in Green ideology. In fact, disease and corruption are also part of Nature; in this particular context horrible sexually transmitted diseases. 'Venereal diseases' we used to call them in bygone days, associating them directly with the goddess herself. For the sufferer, Nature had been more bountiful than intended. For the moment let us allow G. to do what poets do best: peddle pleasant fantasies.

Commentary

In the Prolog Goethe sets out his poetic garden. He presents a double metaphor of a garden of Venus and a garden of the Muses, each of which will ultimately bring forth its respective produce: sexual adventure and his elegies; flowers of love, chosen by the muse.

Every well-disposed visitor is welcome in Goethe's garden of elegies and earthly delights, just not the impotent, enfeebled, critical hypocrites. Priapus, the raw, mischievous, life-affirming spirit, is adjured to humiliate them with sodomisation should they wander into the garden. Sodomy in the classical world was always a power transaction between the dominant older man and the submissive younger man.

Nearly two years after his return to Weimar from Italy, in February and March 1790, Goethe carried out a relatively intensive study of the Carmina Priapea (or simply Priapeia), a collection of around 80-95 short Latin poems on the subject of the 'garden god', Priapus. No one knows who wrote them or collected them together, or exactly when they were written. They have little literary value, being mainly of ethnographic interest.

Their main interest for the modern reader is as evidence that 1) strange thoughts and special interests lurked in some sensitive minds long before the invention of the internet and 2) that the modern person will be hard put to think of any technology-free sexual practice that someone somewhere at some time hasn't already tried out.

Goethe did not just flick through the Carmina Priapea: he annotated some of the poems in Latin and sent the result to his priapic Duke, Carl August. Goethe wrote in Latin to sanitise language that would have been considered shockingly vulgar in the common tongue. For our vulgarities nowadays, now that hardly any one reads Latin and even fewer write it, we have to make do with asterisks. Goethe's scholia is just a curiosity: it brings to light nothing new about his understanding of the Carmina Priapea and certainly nothing that gets us any further in understanding the Römische Elegien.

Goethe wrote Elegy I and Elegy XXIV as bookends for his collection of Römische Elegien. He wrote them with the Carmina Priapea on his mind, but there are also traces of the Augustan elegiasts – the 'triumvirate' as Goethe called them – Tibullus, Propertius and Ovid. In the case of the bookends, Tibullus, a dedicated Priapus fan, is the most present. Goethe's handling of these sources is one more mark of his genius: not a translation but an evocation and an invocation for the modern age (as we discuss more fully under Paralipomena).

The evocation and invocation of the Carmina Priapea in the present elegy presents three main themes: the role of Priapus as the guardian of the garden, the punishment he metes out to trespassers and his bright red member.

We are told of 'the little field consigned to my care' [14:1] and that Priapus is 'the guardian of this fertile garden' [23:1] and the 'faithful guardian of orchards' [73:1].

On the subject of the weapon he wields and his combat techniques against trespassers and thieves, the Carmina Priapea goes into elaborate and prurient detail. The essence of nearly all the punishments is a painful act of sodomy with Priapus' main attribute, which will cause the offender to 'go away more open' (laxior redibit) [16:3]; the weapon will be 'wielded with no mercy' and will penetrate the bowels of the thief, as far as its pubic hair and the bag of balls (intra viscera furis ibit usque / ad pubem capulumque coleorum) [24:6]; it is a weapon that can 'thrust into the biggest thieves' (fures caedere quamlibet valentes) [25:10]. Some detail for the unimaginative reader of the Carmina Priapea: the thief will be sodomised with Priapus' 'foot long phallus' (pedicabere fascino pedali)' [27:3].

The two lines of poem 12 – such a concise language, Latin! – propose a differential treatment for boys (sodomy), girls (fate worse than death) and men with beards (please remove dentures for our comfort and convenience); these different treatments respect the status of sodomy in the classical world as ultimately a power transaction between adults and youths.

The five lines of poem 35 offer a three-step treatment programme for thieves caught in the garden: mouth, sodomy and, for the hardcore recidivist, sodomy followed by mouth (pedicaberis irrumaberisque) [35]. Catullus threatened his friends Aurelius and Furius with a similar fate (pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo) in similar language in his poem 16.

Finally, we also learn from the Carmina Priapea that Priapus' weapon is traditionally painted bright red and thus not to be overlooked – a Roman health and safety measure, it seems.

Goethe's evocation and invocation of the vulgar Carmina Priapea in the Prolog and Epilog of the Römische Elegien would have been a step too far for his contemporaries and so he suppressed them. More than a century had to pass before they could be (discreetly) reinstated. Which was a pity, since the collection lost its 'bookends' and some fine poetry.

Even today, more than a century after they saw the light of day, the bookends rarely find themselves published in the right place to offer their stabilising support to the collection – final score: Hypocrites 1, Priapus 0. By this act of self-censorship the hypocrites won and Priapus was stuffed back in the bushes, out of sight; an irony that was probably not lost on Goethe himself.

II Saget, Steine, mir an, o sprecht, ihr hohen Paläste [1]

Saget, Steine, mir an, o sprecht, ihr hohen Paläste!

1Straßen, redet ein Wort! Genius, regst du dich nicht?

Ja, es ist alles beseelt in deinen heiligen Mauern,

3Ewige Roma; nur mir schweiget noch alles so still.

O wer flüstert mir zu, an welchem Fenster erblick ich

5Einst das holde Geschöpf, das mich versengend erquickt?

Ahn ich die Wege noch nicht, durch die ich immer und immer

7Zu ihr und von ihr zu gehn, opfre die köstliche Zeit?

Noch betracht ich Kirch und Palast, Ruinen und Säulen,

9Wie ein bedächtiger Mann schicklich die Reise benutzt.

Doch bald ist es vorbei: dann wird ein einziger Tempel

11Amors Tempel nur sein, der den Geweihten empfängt.

Eine Welt zwar bist du, o Rom; doch ohne die Liebe

13Wäre die Welt nicht die Welt, wäre denn Rom auch nicht Rom.

Speak to me stones, O speak, you high palaces! Streets, say something! Genius, do you not stir?

Yes, everything has a soul in these sacred walls, eternal Roma; only for me everything remains silent.

O who will whisper to me, in which window will I glimpse the lovely creature who will invigorate me in fire.

Can I not yet know the streets through which I shall again and again go to her and go from her, sacrificing precious time?

Still I look at church and palace, ruins and columns, as a thoughtful man makes fitting use of the visit.

But that will soon be over: then one temple alone will be the temple of love which will receive the consecrated devotee.

You are indeed a world, O Rome; but without love the world would not be the world, and Rome would not be Rome.

Notes

ihr hohen Paläste: 'high' in multiple senses, e.g. physically and socially 'high'.

Genius: The 'genius loci', the spirit of the place.

alles ist beseelt: 'everything has a soul', that is, G.'s reason for coming to Rome is to listen to its stones for himself. At its core, beseelen means 'to animate', 'to bring with life'; just like 'animate', the word can also be used to imply 'bringing happiness or pleasure', but G., the old polytheist/pantheist, clearly had the first meaning on his mind when he wrote ist beseelt.

wer flüstert mir zu: G. is wrestling with the exigencies of metre in this distich. The sense of the passage – once we have read it all – is clearly future, but all future or hypothetical subjunctive variants have to be ruled out. He relies on the word einst to get him out of trouble; it can mean, depending on context, both past and future: 'at some time in the future/past'. It is thus through its own ambiguity a weak helper, though we must have some sympathy for G.'s predicament. In this distich, therefore, our English translation has sacrificed accuracy for comprehensibility and rendered G.'s German in the future tense.

das holde Geschöpf, das mich versengend erquickt: This brilliant construction requires some explanation. It lines up three superficially contradictory terms into what we might term a 'triple oxymoron': holde, 'delightful, sweet, gentle' etc.; versengen, to partially burn or scorch (the etymology is shared with the English word 'singe'); erquicken, to 'refresh, revive, (re)animate'. Versengend is used adverbially to describe the manner of refreshing, which could lead us to some English abomination such as 'singeingly refreshed'. This is the kind of stuff that great poets inflict on defenceless translators.

die Wege…durch die ich immer und immer / Zu ihr und von ihr zu gehn: Stealing through the streets to and from assignations with the loved one (not always without risk) is not just opportunistic poetic imagery, but a frequent situation in the works of the Roman elegiasts who haunt this work. The creeping would-be lover may find the door locked, unlocked or even cracked.

ROMA: The use of the Latin title for Rome (the German word Rom does not work) alludes to its reverse form AMOR (= Cupid), a theme which will be developed in the elegy following. G. seems to be alluding to an old palindrome (attributed to Saint Martin, Quintillian etc.): Roma tibi subito motibus ibit Amor, 'Rome, through movement love will quickly come to you'.

opfre die köstliche Zeit: Goethe was a passionate collector of knowledge; for his time in Rome he had an extensive list of things to see and do, detailed investigations that went far beyond the traditional aristocratic sightseeing of the Grand Tour. He clambered around ruins and monuments, taking measurements and making notes. His absence from the court in Weimar was tolerated by his Duke, Carl August, but his time was not unlimited.

On 17 February 1787 G. wrote to Philipp Seidel, his manservant, who had remained in Weimar:

The quantity of important objects of all types is immense, they just seem to grow out of the ground. In the last few days I have made a catalogue of those things that I have not yet seen. How much there is!

Ungeheuer ist übrigens die Masse wichtiger Gegenstände aller Art, sie wachsen nur wie aus der Erde. In den letzten Tagen macht ich einen Catalogus von dem, was ich noch nicht gesehen habe. Wie viel das ist!

Goethe to Seidel, 17 February 1787.

Goethe had a driven personality – you don't become a 'Universal Genius' by sitting around on elegant sofas – and every hour which he 'sacrificed' to seduction had to have its justification in his proto-Calvinist mind. In contrast, Carl August was an heroic fornicator and self-indulgent pleasure seeker as befitted his station: it would never have occurred to him to consider those activities as a 'sacrifice' of time.

ein bedächtiger Mann schicklich die Reise benutzt: Another image of G. the programmatic collector of knowledge using his time wisely in self-improvement.

It is fair to say that G.'s manic investigations into the art and architecture of Rome and the other Italian cities he visited led to no product that was usable by the rest of mankind but simply served to educate and inform the Universal Genius himself. Even his account of his Italian journey was only written forty or so years later and contributed next to nothing to the sum of human knowledge.

His principal companion during the first months of his stay in Rome, the German painter Tischbein, who pre-loaded G. with some local knowledge, was astonished at the tempo at which G. 'did' the places that interested him. G. was in effect on his own personal odyssey, and like that epic traveller before him he was in pursuit of knowledge through which he would attain to those great, famous epithets of Odysseus: πολύτροπος, 'many-sided', πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, 'many were the men whose cities he saw and whose mind he learned'.

Nowadays we speak of ticking boxes and bucket lists. After experiencing the Roman carneval Goethe told Philipp Seidel in the letter of 17 February 1787 cited above that Das Carneval giebt mir wenig Freude, man gewinnt dabey nur einen sonderbaren Begriff mehr, 'The carnival gives me little pleasure, one gains only yet one more odd notion' – G., the 'knower of men', adding to his collection of odd notions.

Welt: G. is playing upon the phrase urbs et orbis, 'city and world', made familiar by the papal address known as Urbi et Orbi, 'to the city and the world'.

Commentary

Elegies II and III present Goethe's transition from being a mere cultural tourist admiring the silent stones of Rome to being a participant in its ancient sexual freedom. The relationship between the two pieces is unusual: Elegy II describes Goethe the tourist, but prefigures what is to come in Elegy III, the presentiment that love will come to him. Until he has discovered that love, he has not discovered Rome.

In this respect we have to pinch ourselves and remember that we are reading this in beginning years of the 21st century and not the ending years of the 18th. In Weimar, Goethe was only able to see or experience Rome, the remains of a once great civilisation, through a cultural peephole.

The media of the time – printed books with text and a few engravings or paintings of questionable veracity – were incapable of conveying Rome in all the richness of its physical original. Winckelmann waffled on, volume after volume, about the particular glories of classical art – but what good is that if you cannot see it, touch it or experience its monumentality? What Goethe could read or see always came through the filter of someone else's eyes or mind. Goethe wanted to step out of Weimar and step into Rome – as we say: travel broadens the mind. There is more on this theme in the Paralipomena.

Goethe spent almost two years in Italy and almost 16 months of those two years in Rome. There he was confronted with the massive everyday reality (as the phenomenologists put it) of the remains of a culture that bestrode the world. He also practised a total immersion in that environment: he not only attempted to see everything worth seeing first hand, he read classical authors (mainly immediately after his return to Weimar) – particularly those Latin elegists of the Augustan age in the first century BC, who could not have been more different in their vulgar, noisy but stylish eruptions from the pasty-faced, uptight and prudish writers of his era.

Goethe travelled in Italy under an assumed name and kept well away from aristocratic socialising. He was there to see the Rome of the Augustan poets, not the ballrooms of the palazzi. How different from Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), who visited Rome shortly afterwards and spent much time doing the social rounds.

The missionary, brought up in the cloistered certainties of his own faith, ends up in the tropical forest only to discover that they do things differently there, there are other realities: in six months he has 'gone native', is kept busy with three concubines and fortifies himself for this task with the raw brains of his enemies, scooped out of their skulls.

Consider, Reader, the shock of arriving among the monumental ruins of Rome from Weimar; consider, then, the shock of the return. It is in that frame of mind that we must read this elegy, as its first four lines tell us.

III Mehr als ich ahndete schön, das Glück, es ist mir geworden [n1]

Mehr als ich ahndete schön, das Glück, es ist mir geworden;

1Amor führte mich klug allen Palästen vorbei.

Ihm ist es lange bekannt, auch hab ich es selbst wohl erfahren,

3Was ein goldnes Gemach hinter Tapeten verbirgt.

Nennet blind ihn und Knaben und ungezogen, ich kenne,

5Kluger Amor, dich wohl, nimmer bestechlicher Gott!

Uns verführten sie nicht, die majestätschen Fassaden,

7Nicht der galante Balkon, weder das ernste Kortil.

Eilig ging es vorbei, und niedre zierliche Pforte

9Nahm den Führer zugleich, nahm den Verlangenden auf.

Alles verschafft er mir da, hilft alles und alles erhalten,

11Streuet jeglichen Tag frischere Rosen mir auf.

Hab ich den Himmel nicht hier? — Was gibst du, schöne Borghese,

13Nipotina, was gibst deinen Geliebten du mehr?

Tafel, Gesellschaft und Kors’ und Spiel und Oper und Bälle,

15Amorn rauben sie nur oft die gelegenste Zeit.

Ekel bleibt mir Gezier und Putz, und hebet am Ende

17Sich ein brokatener Rock nicht wie ein wollener auf?

Oder will sie bequem den Freund im Busen verbergen,

19Wünscht er von alle dem Schmuck nicht schon behend sie befreit?

Müssen nicht jene Juwelen und Spitzen, Polster und Fischbein

21Alle zusammen herab, eh er die Liebliche fühlt?

Näher haben wir das! Schon fällt dein wollenes Kleidchen,

23So wie der Freund es gelöst, faltig zum Boden hinab.

Eilig trägt er das Kind in leichter linnener Hülle,

25Wie es der Amme geziemt, scherzend aufs Lager hinan.

Ohne das seidne Gehäng und ohne gestickte Matratzen

27Stehet es, zweien bequem, frei in dem weiten Gemach.

Nehme dann Jupiter mehr von seiner Juno, es lasse

29Wohler sich, wenn er es kann, irgend ein Sterblicher sein.

Uns ergötzen die Freuden des echten nacketen Amors

31Und des geschaukelten Betts lieblicher knarrender Ton.

More so than I ever hoped, happy good fortune is mine; Cupid guided me cleverly past all palaces.

He has long known, just as I have learned, what hides in a gilded room behind curtains.

Though he is called blind and a boy and cheeky, I know you well, clever Cupid, you incorruptible god!

We are not seduced by them, the majestic facades, nor the gallant balcony nor the imposing courtyard.

We hurried past until a low, pretty doorway received the guide and received the longing one together.

He arranged everything for me, helps in everything and gets everything, spreads every day ever fresher roses upon me.

Am I not in heaven here? – what do you give, beautiful Borghese, Nipotina, what more do you give your loved one?

Dinner, society and promenades and games and opera and balls, robbing Cupid of his most opportune moments.

Decoration and frippery revolts me, and in the end is not a brocaded dress lifted just like a woollen one?

Or if she wants to hide her friend pleasingly in her bosom, does he not just want to rid her of the jewellery without delay?

Don't all those jewels and lace, padding and whalebone have to come down before he can even feel the loved one?

It's simpler for us! Your woollen dress, just loosed by your friend, falls in folds onto the floor.

Quickly he carries the child, in a light linen chemise, as a midwife might, playfully onto the bed.

Without silken tapestries and without embroidered mattress it stands there, comfortably for two, free in the spacious chamber.

Should Jupiter take more from his Juno, it would be more enjoyable, if he can, to be somehow a mortal.

We delight in the pleasures of the true naked Cupid and the gently creaking sound of the rocking bed.

Notes

Cupid: The agent of Venus, the friend of the lover and the enemy of the reluctant, the naked boy appears on many occasions in the elegies, as he does in all the Roman elegists who were Goethe's models.

klug allen Palästen vorbei: Goethe was not without rank: in addition to his literary fame he had been ennobled in 1782 and was a Privy Councillor in the service of Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach. It would have been easy for him to have moved in the elevated circles of the Roman aristocracy and spent his time in dalliance with the noble ladies of Roman society. But he had plenty of that in Weimar, where the frivolity of the court and its brainless amusements frequently irritated him. Cupid, the agent of Venus, 'cleverly' kept him away from such distractions during his time in Rome.

His attempt at remaining incognito in Italy, and in Rome in particular, was generally successful; it allowed him to stay out of the palaces of the high and mighty. The habit of travelling incognito was widespread at the time: in the case of the famous, such as the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, a manic traveller across huge distances, the technique of travelling under an assumed name allowed both the visitor and the visited to dispense with annoying formalities and protocol. Joseph liked to think that he was seeing the realities of his empire on these journeys, but this is doubtful, since wherever he went people knew who he was. Returning once from a visit to Paris, Joseph, who liked to style himself the 'enlightened emperor', allegedly – allegedly – detoured in his carriage at the last minute from a meeting with Voltaire because of the showy welcome that Voltaire had arranged.

For G. it was not just the high and mighty he wished to avoid: he went out of his way to stay clear of all social involvements, apart from a few trustworthy Germans he had met:

I had barely arrived in Rome before I was recognised, but I have stuck to my incognito, I just visit the sights and reject all other relationships.

Kaum war ich in Rom angekommen als ich erkannt wurde doch führ ich mein Incognito durch, sehe nur die Sachen und lehne alle andern Verhältniße ab.

Letter to his manservant Philipp Seidel, 9 December 1786.

nimmer bestechlicher Gott: Cupid, in taking G. away from all the seductive attractions of aristocratic life in Rome, demonstrates his single-minded incorruptibility – a rare characteristic in the Rome of that time.

Kortil: 'Courtyard', (Italian cortile, courtyard)

majestätschen Fassaden…galante Balkon…ernste Kortil…zierliche Pforte: G.'s fevered brain is having some fun with this erotic progression down the 'majestic facades' of the bodies of noble Roman ladies.

Balkon: is even today a slang word in German for an imposing bosom; galant was frequently used as a synonym for 'amorous' in G.'s day. At the end of G.'s lascivious journey down the female facade he and Cupid arrive at the low, 'pretty doorway'.

schöne Borghese…Nipotina: This passage continues to baffle and confuse even present-day commentators (your author included).

The Italian scholar, Roberto Zapperi, disentangled with great persistence some of the multi-layered allusions. He maintains that the term schöne Borghese refers to Princess Livia Borghese (1669-1732, née Spinola), who married Marcantonio III Borghese, third Prince of Sulmona, in 1691.

But Livia had been dead more than 50 years by the time G. was in Rome and left little trace of herself for posterity. In G.'s time, the phrase schöne Borghese would surely call to mind Princess Anna Maria Salviati (1752-1809), the wife of Marcantonio IV Borghese, fifth Prince of Sulmona (1730-1800) and a senator of the Roman Republic. They married in 1768. She herself was the last of a distinguished and rich Italian dynasty and brought all its assets into the marriage. Thanks to Marcantonio's energy the Borghese court (Villa Borghese) was a leader of Roman society at the time G. was there.

Zapperi, however, thinks that G.'s reference to schöne Borghese was actually a cover name to hide the identity of the real person behind G.'s reference, who, according to Zapperi, was Costanza Braschi-Onesti, née Falconieri, the wife of Prince Luigi Braschi-Onesti (1745-1816), Duke of Nemi. They married in 1781. The novel based on their lives has yet to be written – but it would be a fat one with chapters of triumph and disaster, immense riches and losses, all resting on gossip, patronage, nepotism and extremely shady deals.

Nepotism is the key element in their tale. Luigi's mother was Giulia Braschi, the sister of Giannangelo Braschi, who became pope in 1775 and who took the name Pius VI (1717-1799), which made Luigi his nepote, nephew. Luigi leveraged the patronage of his uncle, the Pope, and acquired money, patrimony and rank. For example, when the Jesuits were disbanded in 1781 Luigi scooped up some of their choicer assets at fire-sale prices. Even an outline account of Luigi's dealings in this period, aided and abetted by his uncle, would fill many paragraphs here.

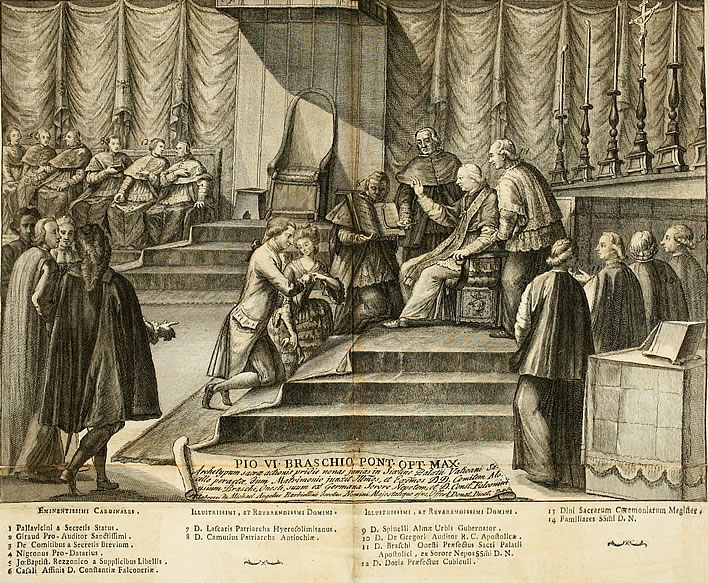

In 1781 he married Costanza, from the renowned and rich Falconieri family. The marriage took place in the Sistine Chapel, no less, and was presided over by Pius VI himself, no less:

Matrimonio fra Luigi Braschi Onesti e Costanza Falconieri, celebrato da Pio VI il 4 giugno 1781, etching by Michelangelo Barbiellini, c. 1781. [Click to open larger image in a new browser tab.]

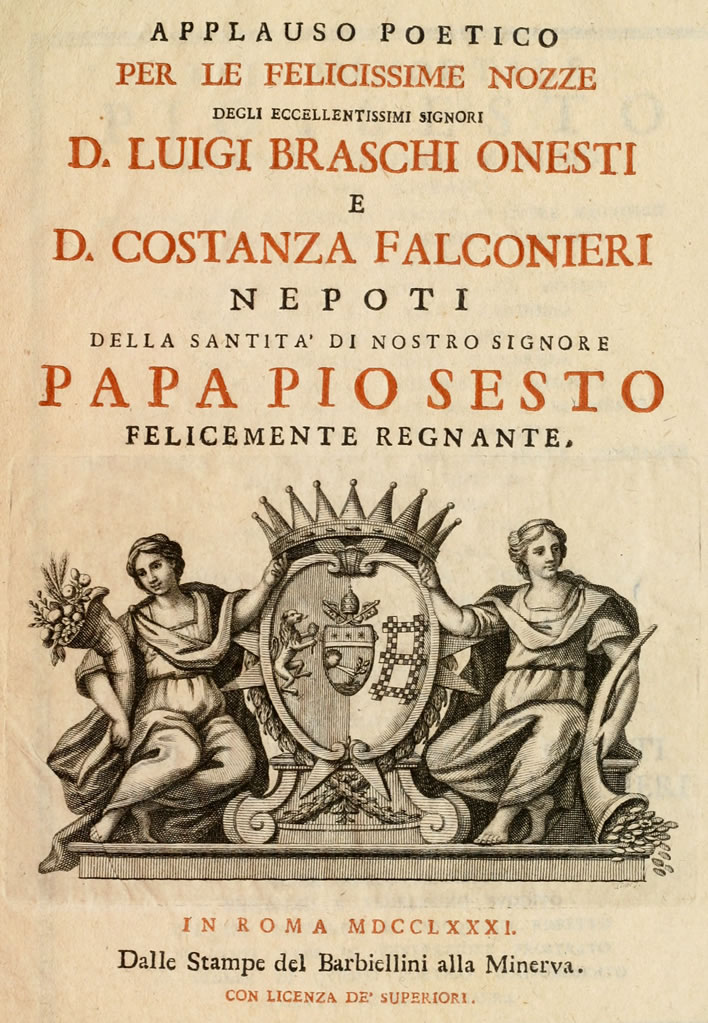

If you are the Pope's nephew and niece, you may as well flaunt that fact, the importance of which is indicated in the differential sizes of the typeface. The effect of that nepotism is shown in the overflowing horns of plenty, one with agricultural produce, the other with money. 'Twas ever thus: if you've got it, flaunt it. Applauso poetico per le felicissime nozze degli eccellentissimi signori D. Luigi Onesti e D. Costanza Falconieri, nepoti della santità di nostro signore papa Pio Sesto felicemente regnante, engraved by Michelangelo Barbiellini, 1781.

Luigi and Costanza led a lifestyle befitting their wealth and station and were the subject of much gossip and scandal. For the purposes of rumour Luigi became known under the brand name of Nepote or Nipotino and Costanza thus became the Nipotina. The pair shared a moral compass without a needle, leading to much gossip about lovers and illegitimate children.

There can be no doubt that G.'s explicit use of Nipotina in the wider context of aristocratic decadence is a solid pointer to Costanza. Zapperi also points out that the Italian translation of G.'s scandal novel Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, was not only done by Vincenzo Monti, the secretary of the ducal pair, but was also dedicated to Costanza – a fact which G. would surely have known and which explains his attention to the Nipotina. Rumour has it that Monti was more than a secretary to the Duchess and that he was the father of her daughter Giulia. Monti, despite G.'s wish to maintain his incognito and avoid socialising in general, had several contacts with G. during his time in Rome.

Vincenzo Monti, unknown artist, undated. Readers may be struck by the similarity between the likeness of Monti and that of Goethe.

But why, having given his readers such a substantial pointer to a member of the Roman aristocracy, would G. want to mask her identity? And, most puzzling, in masking it, why would he use the name of an equally illustrious member of that aristocracy? He is writing this elegy in Weimar and can hardly fear Roman reprisals. Furthermore, this elegy was one of the four that he suppressed and which were only published more than a century later, so that the entire exercise in obfuscation was ultimately pointless. G.'s woollen skein of allusions has become so tangled here that unpicking it is a task beyond mortals: 'Paging Herr Geheimrat Goethe!'

Kors': ='Corsa', alluding to the traditional evening promenade along the Corsa in Rome (where G. resided), an opportunity for Roman society to see and be seen.

Tafel…Bälle: A good summary of life among the butterflies, whether in Rome or in Weimar. G. was in Rome during the carnival. He expressed his distaste for such things in a letter to his Weimar manservant Philipp Seidel on

I hardly ever go to the theatre, one doesn't want to expend any time at all on this tomfoolery, because there are so many opportunities for solid observations.

In die Theater komme ich auch fast gar nicht, man mag hier gar keine Zeit auf diese Gauckelpoßen verwenden, da man zu so viel soliden Betrachtungen Gelegenheit hat

17 February 1787.

frischere Rosen: 'ever fresher'. G. is a careful user of German, even when he has a metre to be matched. We should therefore try to reproduce his superficially odd comparative adjective 'frischere' with fitting accuracy. If roses are the euphemistic symbol that we think they are, then getting them 'ever fresher' every day seems an interesting prospect.

Ekel bleibt mir Gezier und Putz: The force of Ekel, 'revulsion' comes as a surprise. It is directed at Gezier und Putz decoration, ornamentation, dress and makeup, but it is part of a general and deep-seated contempt that G. had for the aristocracy and the administration in Rome.

fällt…faltig zum Boden hinab: faltig, 'folded, in pleats', an example of G.'s mastery of telling detail: the simple, soft woollen dress lies in folds on the floor, whereas the stiff, architectural gown could almost stand on its own without additional support. We remember here the 'facades' of the noble Roman women. We also note the melodious juxtaposition of fällt and faltig.

seidne Gehäng: 'silken hangings' could be curtains or tapestries. In the days when domestic servants were everywhere, curtains around the bed were an essential and functional item of decoration.

Jupiter…Seiner Juno: The marks of the grammatical hammer, crowbar and pliers which G. used to bend German into the shape of this distich are unmissable. The meaning is that Jupiter and his Juno, those serial couplers, would be happy to have the pleasure that the mortals Goethe and his Roman lady experience in that simple bed. The distich makes perfect sense once you know what it means.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Jupiter and Juno, a panel of the ceiling fresco in the Farnese Gallery, Rome, on the theme The Loves of the Gods (1597). The panel depicts a scene from Book 14 of the Iliad, in which Juno (symbol: peacock) seduces Jupiter (symbol: eagle) on the Mount of Ida with the aid of the the magic sash given to her by Venus in order to divert his attention from the Trojan War and so give the Greeks the advantage.

James Barry (1741-1806) Jupiter and Juno, c1804-5, from a series of etchings. Image: Tate London.

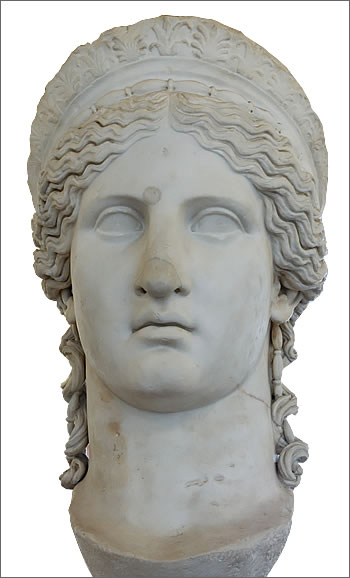

The Juno Ludovisi in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome. It is named after the Ludovisi Collection.

In Rome in 1786/1788, Goethe stayed in the extensive apartment-studio of the painter Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829) (in Rome 1779-1781, 1783-1799). Goethe acquired a monumental plaster mask of a sculpture of the 'head of Juno', the so-called 'Juno Ludovisi', (and numerous smaller images of her) and set them up in his bedroom. A copy of this sculpture found its way back to Goethe's house in Weimar, where it stands today.

Commentary

Elegy III brings the presentiments of the preceding elegy into existence. Cupid has guided Goethe to the passionate woman who will provide the sensual component of the Roman experience. The choice of the simple woman as lover is simultaneously the rejection of the complex aristocratic affair, the rejection of all aristocratic trappings.

Goethe disliked the fatuous lifestyle he had to put up with at the court of Weimar: 'dinner, society and promenades and games and opera and balls', his Duke's passion for hunting, especially boar hunting, which damaged his tenants' crops and fields, and for pig-sticking races and the need to provide a conveyor belt of entertainment to keep the courtiers and their ladies amused, these were all things he had to put up with as a trade off for the fulfilling parts of his job and the freedom to write.

After nearly ten years in the Weimar court, he went from a commoner who was not allowed to dine with the noble courtiers to being a trusted counsellor who was finally himself ennobled. But the freedom to write had been eroded by those administrative duties which he also took seriously, so that in those ten years his literary output had dwindled.

He was a literary sensation when he had entered the Duke's service; after ten years he had become a far-sighted administrator with a considerable workload. After fleeing to Italy in desperation, the last thing he was going to do was to seek comfort in an aristocratic lifestyle not much different from the one he had left behind him.

This elegy was self-censored in the collection, we would initially assume because of the eroticism of the dress dropped in folds on the floor, the woman in only a simple chemise carried to the bed and the creaking bed hinting at the act of darkness, the beast with two backs. Goethe's Duke was himself a libertine of the first chop and might have coped with such eroticism, though he advised against publication.

But when we consider the contemptuous and undisguised rejection in the elegy of the aristocratic lifestyle and aristocratic women, we realise how difficult it would have been for the denizens of the court of Weimar to stomach an elegy such as this one.

Carl August understood his court sage and had understood, too, how much Goethe's presence (and the writers he had brought to Weimar with him) contributed to the European reputation of his court. If Carl August is remembered today it is because of his patronage of Goethe and the three other literary 'stars' in Weimar, Wieland, Herder and Schiller; without them the Duke would be just another long-forgotten, pig-sticking nob. Goethe made his prince immortal.

Goethe may have been repulsed by the disorder and excesses of the French Revolution, but his heart had its Jacobin moods and found it in himself to admire Napoleon as a fellow genius, to his Duke's occasional discomfiture.

We must never forget that the Römische Elegien were not written contemporaneously during his time in Italy. He began work on them after his return to Weimar and their production took him nearly two years. As would be the case with his autobiography, Dichtung und Wahrheit, the Elegien were a product of much reflection and considerable artifice. Nothing in them is spontaneous, everything carefully considered and structured – the thoughts behind them as carefully formed as the metre of the language. That is why we have to read them so carefully, for every word counts and every scene is there for a reason.

After his return to Weimar, in July 1788 the 48 year-old took up with the 23 year-old milliner Christiane Vulpius (1765-1816). She was a commoner from an impoverished family, quite outside the pale of the Weimar court. Her scandalous status as Goethe's live-in concubine put her even further outside that pale. The high-born ladies of the court largely shunned her.

On his return to Weimar, therefore, at the time he began the Römische Elegien, Goethe's real life situation mirrored exactly the situation described in this elegy: he had rejected the over-decorated aristocratic bedchambers with their over-decorated occupants and, guided by Cupid, settled for the spacious bedroom with the unpretentious, compliant young woman in a simple bed.

In Weimar he moved Christiane in with him, where she, with their illigitimate son August (1789-1830) (four other children died as infants) remained in a concubine's limbo for 18 years.

As we have seen elsewhere, Goethe could simply not commit to a relationship, no matter how happy it was. In 1806, during the French occupation of Weimar, she bravely and alone faced down the plundering French troops until Goethe could organize official protection for the house. Only then, a few days later, did he marry her. She died on 6 June 1816. Goethe did what Goethe always had done: he absented himself from the agonies of her deathbed, he cried a few tears, left her grave untended and moved on to younger models.

IV Ehret, wen ihr auch wollt! Nun bin ich endlich geborgen! [2]

Ehret, wen ihr auch wollt! Nun bin ich endlich geborgen!

1Schöne Damen und ihr, Herren der feineren Welt,

Fraget nach Oheim und Vetter und alten Muhmen und Tanten;

3Und dem gebundnen Gespräch folge das traurige Spiel.

Auch ihr übrigen fahret mir wohl, in großen und kleinen

5Zirkeln, die ihr mich oft nah der Verzweiflung gebracht,

Wiederholet, politisch und zwecklos, jegliche Meinung,

7Die den Wandrer mit Wut über Europa verfolgt.

So verfolgte das Liedchen „Malbrough” den reisenden Briten

9Einst von Paris nach Livorn, dann von Livorno nach Rom,

Weiter nach Napel hinunter, und wär er nach Smyrna gesegelt,

11Malbrough! empfing ihn auch dort, Malbrough! im Hafen das Lied.

Und so mußt ich bis jetzt auf allen Tritten und Schritten

13Schelten hören das Volk, schelten der Könige Rat.

Nun entdeckt ihr mich nicht sobald in meinem Asyle,

15Das mir Amor der Fürst, königlich schützend, verlieh.

Hier bedecket er mich mit seinem Fittich; die Liebste

17Fürchtet, römisch gesinnt, wütende Gallier nicht:

Sie erkundigt sich nie nach neuer Märe, sie spähet

19Sorglich den Wünschen des Manns, dem sie sich eignete, nach.

Sie ergötzt sich an ihm, dem freien, rüstigen Fremden,

21Der von Bergen und Schnee, hölzernen Häusern erzählt;

Teilt die Flammen, die sie in seinem Busen entzündet,

23Freut sich, daß er das Gold nicht wie der Römer bedenkt.

Besser ist ihr Tisch nun bestellt; es fehlet an Kleidern,

25Fehlet am Wagen ihr nicht, der nach der Oper sie bringt.

Mutter und Tochter erfreun sich ihres nordischen Gastes,

27Und der Barbare beherrscht römischen Busen und Leib.

Honour whomsoever you wish! Now at last I am in safety! Beautiful ladies and you, lords of the finer world;

Ask about uncle and cousin and old aunts and aunts; and let polite conversation follow the tragedy.

The rest of you, too, drive me around in great and small circles, bringing me close to despair,

Repeat, politically and pointlessly, all those opinions, which angrily follow the traveller right across Europe.

Thus the song 'Malbrough' pursues the British traveller from Paris to Livorno, then from Livorno to Rome,

then further down to Naples and were he to sail to Smyrna, the song Malbrough! would also be there to greet him, Malbrough! in the harbour.

And every step of the way until now I have had to listen to the curses of the people and the curses of the King's council.

Now they will not find me in my asylum, which Cupid the prince, regally protective, bestowed on me.

Here he covers me with his wing; the loved one, thinking only of Rome, has no fear of the raging French:

She does not inquire after new tidings, she focuses carefully on the desires of the man, to whom she has given herself.

She takes delight in him, the free, hearty foreigner, who speaks to her of mountains and snow and of houses built of wood;

Shares the flame, which she has lit in his breast, is happy that he does not look upon gold as the Romans do.

Her table is now more richly laid; there is no lack of clothes, nor is the carriage lacking that takes her to the opera.

Mother and daughter are happy to have their guest from the North, and the barbarian takes possession of Roman bosom and body.

Notes

Ehret, wen ihr auch wollt!: As we shall see shortly, G. tells us that one reason for him to flee to the anonymity of Rome was that he wanted to escape the continual fuss made of the author of 'Werther'. G. has developed the original Fraget, 'ask' in the Ms. into Ehret, 'honour' to provide the reader with a small (but ineffectual) clue that he is talking about his 'Werther' fame. However he does recycle Fraget at the start of the next distich.

Nun bin ich endlich geborgen!: Geborgen, 'hidden', 'protected', 'safe and secure'. It is important to realise that G. is not simply 'safe and secure' because he is far from the court of Weimar and now a stranger in a strange land, with a forwarding address only his faithful manservant, Philipp Seidel knew.

He is protected by the pseudonym he has adopted: Johann Philippe Möller ('Johann' sometimes became 'Jean'). The author of the scandal novel Werther was anything but safe in Rome. In a Protestant country, the dislike of the religious authorities for Werther, with its romantic suicide for love, was bad enough, but in Rome Goethe was uniquely vulnerable: he was at the epicentre of Catholicism in a state where the enlightened distinctions between religious and secular authority were almost non-existent. It is for this reason that the first part of this elegy concentrates on his notoriety as the author of Werther.

alten Muhmen und Tanten: 'old aunts and aunts'. There is no real difference between die Muhme und die Tante, they both mean 'aunt'. Since 'aunt' has no synonym in English your translator has to accept defeat.

dem gebundnen Gespräch: 'bound conversation' = 'courteous' or 'courtly' conversation. Bound by convention and formality, as opposed to free and unrestricted conversation.

ihr übrigen: 'the others', in the sense of 'commoners', in contradistinction to the 'ladies and lords'.

politisch und zwecklos: 'politically and pointlessly' – some commentators take 'politisch' to be an allusion to the debates then raging about the French Revolution. Your author, however, following the punctuation, prefers to see this as a further development of the 'Werther' furore which followed Goethe wherever he went.

Grammar supports this view, in that it is not the opinions as such that are political or pointless, but their repeated expression. By using the adverbial forms governing the verb 'repeat', G. is stating that the expression of the opinion is political and pointless, that is, it is itself a political act. The opponents of 'Werther' need to be seen to be opposing it. He is pointing to the fact that the fierce opposition to 'Werther' was not literary or critical in character, but political (or religious-political) in nature.

This interpretation sits well with the subsequent description of the controversy as following den Wandrer mit Wut über Europa, 'angrily follow the traveller right across Europe' – the traveller being G.

Malbrough: the mocking folk song Marlbrough s'en va-t-en guerre, 'Marlborough is off to the wars' originated in France, so we can't expect them to spell the Duke of Marlborough's name correctly. The song has a jolly tune, which ensured its popularity. The words celebrate the rumoured death of the Duke at the battle of Malplaquet in 1709 and thus would have been an irritant to any British person hearing them. In fact, the Duke survived Malplaquet unscathed (unlike the 24,000 dead and wounded on the British side alone) and continued his glorious career until his death in 1722.

die Liebste: 'the loved one'. G. went out of his way to keep the name of his Roman lover private; it has stayed private ever since, despite the usual scholarly game of 'find the lady'. In the same way, we have to accept the intriguing expression Mutter und Tochter, 'mother and daughter' at its face value.

And here we must issue a health warning that is valid for all the Römische Elegien (and arguably for all his poetry and a lot of his prose), one which we shall find ourselves repeating again and again. Even when we have managed to decipher G.'s mystifications, we are still nowhere near any coherent reality. This is all slight of hand, it is Dichtung not Wahrheit. In fact, two health warnings are needed here.

First health warning: This elegy gives the reader the impression that G. fled to Rome to escape his Werther notoriety and found a safe haven in his lover's bed under Cupid's protective wing. But G. has telescoped reality for the sake of his narrative: the reality is that he arrived in Rome on the evening of 29 October 1786, after some sightseeing on the way. After overwintering for nearly four months in Rome, he set off on a four month tour of southern Italy that took him to Naples and Sicily. He returned to Rome in June 1787, where he stayed for around eleven months. If we believe Roberto Zapperi's reconstruction, it was only in the last three or four months of his stay that he was with his Liebste. Thus, if we pull out the telescope of G.'s narrative, we find that Cupid's wing did not stretch protectively over him until he had been in Rome for more than a year. Until Cupid came to call in December 1787 he had to make do with occasional, risky financial transactions with the ladies of the Italian night.

Second health warning: G. wrote his elegies in chilly Weimar, not in Rome, whilst he was in the first years of his relationship with Christiane Vulpius. This fact produced a creative distance to his project Römische Elegien which allowed him to undertake it with great objectivity. Furthermore, the elegiac construction itself encourages a declarative style of narrative. Nun bin ich endlich geborgen!, 'Now at last I am in safety!' – not false in a strict sense, in that there is always a 'now', whether in Rome or Weimar, but not to be taken at its supposed face value. G. found this habit in the Latin poets whom he took as models: Tibullus, Propertius, Ovid, Catullus and Horace. When reading them, questions of truth, sincerity and satire have usually to be uppermost in the reader's mind, just as they must be with G. writings.

wütende Gallier: 'raging French', alluding to the turmoil of the French Revolution. Reality check: the French started raging in earnest at the Fall of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, which is generally taken as the moment at which the French Revolution began. G. had left Rome in the spring of the previous year, so the 'raging French' would have only claimed his attention in Weimar, not in Rome.

In 1792, whilst his Römische Elegien were still in manuscript form, he had been dragged by his Duke to share with him the humiliating defeat of the allied forces at the hands of the enraged French at the Battle of Valmy, close to the eastern frontier of France. He documented this dispiriting experience in his prose work Kampagne in Frankreich 1792. This was yet another of G.'s works that affected contemporaneity but which was in fact written thirty years after the fact.

neuer Märe: 'new reports/rumours/tales', presumably about the French Revolution, which had started in earnest in July 1789, the year after Goethe had left Italy. The colonies of expatriate French aristocrats who had taken refuge in German and Austrian countries were adept at stirring the pot by circulating rumours about events in France, the grislier the better, all with the aim of persuading the Austrians and the Prussians to invade France, topple the revolutionaries and give the expatriates their chateaux back.

das Gold nicht wie der Römer bedenkt: G. mystifies everyone except Latin scholars with this extremely oblique allusion, which seems initially to refer to Propertius II.16.12: Cynthia non sequitur fascis nec curat honores, / semper amatorum ponderat una sinus. 'Cynthia cares nothing for rules or titles, but considers only the size of the purse' ['sinus: The purse, money, which was carried in the bosom of the toga', Lewis and Short tell us.] We are touched by Propertius' irritation that his beloved Cynthia doesn't prostitute herself to men on the basis of aristocratic rank, but rather does it for money.

This seems to be what G. means with wie der Römer bedenkt, 'as the Romans thought'. Propertius continues on this theme: numquam Venales essent ad munus amicae, / atque una fieret cana puella domo, 'Girls would never sell themselves for a gift, and would grow grey in one house alone'. Touching, too, that he seems to believe that a girl should grow old along with her Augustan elegist. In contrast, G. and his lover have no inhibitions about money.

An important influence on the Römische Elegien was Tibullus, who praised the simple, unpretentious, rustic lifestyle. He frequently grumbled at the corruption of emotion by money, particularly the way a beautiful boy or girl could be bought out from under him by the rich and elderly with money and expensive presents:

Unfortunately our perverse age has brought some miserable practices – these days a tender young boy will expect a gift. Whoever you are who first taught the sale of love, may a boulder lie heavy on your bones. Love the Pierides, boys, and love skilled poets; may the daughters of Pierus never succumb to golden presents.

Heu male nunc artes miseras haec saecula tractant: / Iam tener adsuevit munera velle puer. / At tu, qui venerem docuisti vendere primus, / Quisquis es, infelix urgeat ossa lapis. / Pieridas, pueri, doctos et amate poetas, / Aurea nec superent munera Pieridas.

Tibullus 1.4:57:64. NB: 'Pierides' is probably used here in the sense of the Muses.

Flee, [Delia], as soon as possible, the grasping witches' school; All bought lovers can be outbid by presents. A poor man will always be in your service; he will come to you first and hold fast to your gentle side; A poor man, a trusty escort in the jostling crowds, gives you his arm and makes a way. A poor man will take you privately to the dwellings of secret friends and himself take off the sandals from your snow-white feet.

At tu quam primum sagae praecepta rapacis / Desere, nam donis vincitur omnis amor. / Pauper erit praesto semper, te pauper adibit / Primus et in tenero fixus erit latere, / Pauper in angusto fidus comes agmine turbae / Subicietque manus efficietque viam, / Pauper ad occultos furtim deducet amicos / Vinclaque de niveo detrahet ipse pede.

Tibullus 1.5:59:66.

My boy has been captured by gifts – but may the gods turn them to ashes and running water.

[…]

Then you would swear to me that for no weight of gold or jewels would your fidelity ever be sold.

[…]

Go far away, you whose aim is to sell your beauty and return with a great payment filling your hand. And you who dared corrupt the boy with gifts, may your wife humiliate you unpunished with her intrigues and when she has exhausted her lover in a furtive tryst, let her lie spent beside you, with the coverlet between you;

Muneribus meus est captus puer, at deus illa / In cunerem et liquidas munera vertat aquas.…

Tum mihi iurabas nullo te divitis auri / Pondere, non gemmis, vendere velle fidem,…

Tu procul hinc absis, cui formam vendere cura est / Et pretium plena grande referre manu. / At te, qui puerum donis corrumpere es ausus, / Rideat adsiduis uxor inulta dolis, / Et cum furtivo iuvenem lassaverit usu, / Tecum interposita languida veste cubet. …

Tibullus 1.9:11,30,51.

der Barbare beherrscht römischen Busen und Leib: Once more some headscratching is caused by an allusion to Propertius II.16.27. In this passage Propertius is torturing himself with images of his Cynthia, currently in Illyria, her white arms wrapped around some ugly barbarian brute: barbarus exclusis agitat vestigia lumbis, / et subito felix nunc mea regna tenet!, 'A barbarian denied the pleasure of his loins stamps his foot and suddenly he has now taken the kingdom where I ruled'. Well, we chaps have all been there. In Latin barbarus was applied to any non-Roman; G. can only gloat that he, the barbarian from the north, is now ruling this particular roost.

Commentary

Readers should not be ashamed if they are left completely baffled by most of this elegy: they are in a majority and in good company at that. There is a structure of ideas in the elegy, but Goethe has scrumpled it down to a density that can only be unpacked with specialist tools.

The first three distichs are actually a summary of Goethe's desperation at his immense fame as the author of Die Leiden des jungen Werthers, that scandalous epistolary novel from 1774 which propelled Goethe to pan-European fame and notoriety within a few weeks of its appearance. The tragic suicidal end of Werther, who had no hope of obtaining his love Lotte, engaged to one Albert, had young female hearts fluttering and red ink from the pens of wizened censors covering the pages. It was a glorification of passion beyond all reason and a justification of suicide as the noble option.

But as every modern celebrity will tell you on social media, when the sugar rush of sudden fame has passed, there follow years of discussing the same old things with an endless stream of ever more adoring disciples. In Goethe's case, by the time of his flight to Italy he had had to cope with twelve years of Goethe frenzy.

Goethe's first handwritten version of this elegy gives us a glimpse of what was going on in his head at the time. However, in the first printed edition he substantially rewrote the first four distichs of the elegy, throwing a veil of obscurity over the original clarity and causing all the earlier explicit links to 'Werther' to be broken.

This major rewrite is just one of the many instances we find throughout Goethe's works of quite deliberate mystification, particularly in respect to his own participation. It seems to be true that, although his literary work is ultimately 'all about him', as we say these days, Goethe frequently chose to take a step back and become the distanced, Joycean artist, standing like God behind his work, paring his fingernails. Hence the retreat from this honest biographical sketch:

Fraget nun wen ihr auch wollt mich werdet ihr nimmer erreichen

1Schöne Damen und ihr Herren der feineren Welt!

Ob denn auch Werther gelebt? Ob denn auch alles fein wahr sey?

3Welche Stadt sich mit Recht Lottens der Einzigen rühmt?

Ach wie hab ich so oft die thörigten Blätter verwünschet,

5Die mein jugendlich Leid unter die Menschen gebracht.

Wäre Werther mein Bruder gewesen, ich hätt ihn erschlagen,

7Kaum verfolgte mich so rächend sein trauriger Geist.

Ask whomsoever you like, you will never reach me, beautiful ladies and you lords of the finer world!

Whether Werther had really lived? Whether all was completely true? Which town can truly say it is Lotte's town?

O how often I have wished that the stupid pages no longer existed which brought my youthful suffering to the notice of the people.

Had Werther been my brother, had I struck him dead, his tragic spirit would have scarcely followed me so vengefully.

The careless honesty of these distichs is quite surprising for anyone who knows Goethe's work. For example, a standard topic in essays on the young Goethe is the question: 'how much Goethe is there in Werther?'. In these early manuscript distichs, Goethe has just answered the question: 'my youthful suffering'.

Goethe, however, was always the dumper, not the dumped, and committing suicide for the love of a woman is simply not in his psychological make-up – he preferred to leave his women gasping for more of him, forelorn, distraught at the thought of having to spend the rest of their lives in the company of inferior men. If anything, the women were the ones who were supposed to shoot themselves. He would get a poem or two out of it and move on. 'I had not loved thee half so well, loved I not womankind' [@Ezra Pound].

Apart from Goethe's general hang to mystification, why did Goethe scramble these distichs on 'Werther' into almost total incomprehensibility? In removing himself, he left only dangling threads of unanswered questions behind.

We don't know. We can only speculate that Goethe, back in Weimar and no longer in the anonymity of his Roman refuge, was once again exposed to his critics, literary and social. In this situation, the breast-beating of the manuscript must have become uncomfortable – there were plenty of people who would enjoy beating his breast for him, who would crow at his admission that the creation of 'Werther', a work to which so many important people had taken offence, had been an error which he now deeply regretted.

That the author of Werther was now writing erotic poetry about his time apparently bedded down with a nameless kept woman in Rome was just one more red laser-dot glowing on his chest. The poet, translator and Protestant theologian Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), whom Goethe had persuaded to move to Weimar, waspishly remarked that Schiller, who had published twenty of the elegies in his literary magazine Die Horen, 'The Horae' ('The Seasons') should really now rename his magazine, only needing to change one letter, as Die Huren, 'The Whores'. Duke Carl August, party to the muttering resentment of his Privy Councillor that swirled around his court, had advised against any publication at all. Fortunately for us, Goethe did not take his advice.

Just like celebrities ever since, therefore, at least one of Goethe's motives for the journey to Italy was the search for anonymity, a flight away from the shadow of notoriety which clung to his heels after the publication of Werther.

The book remained officially banned in many European jurisdictions for many years, under particular pressure from the religious authorities who objected to suicide on principle and from the civilian authorities who suspected that it might lead to a fashionable wave of young chaps shooting themselves incompetently in the head. Despite all the best efforts of the authorities, banned books and their buyers would always find each other, albeit at great expense, meaning that it was the youthful well-to-do who were most exposed to the book's evil effects.

Wilhelm Amberg (1822-1899), Vorlesung aus Goethes Werther, 1870. This painting can be taken at its sentimental face value or as a satire on sentimentality, depending on the viewers disposition: tears and laughter are both allowed. Image: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie.

Goethe's handwritten version of the elegy also clears up another mystification: the meaning of his description of the spread of the French ditty 'Malbrough', for now the connection has been restored: Kaum verfolgte mich so rächend sein trauriger Geist. | So verfolgte das Liedchen „Malbrough” den reisenden Briten. Just as Goethe was confronted with Werther wherever he went in Europe, so the British traveller was confronted with the silly ditty 'Malbrough'. Only now 'endlich geborgen' with his love, is he secure from the annoying questions of his fans.

In the manuscript version of this elegy, Werther was uniquely singled out as the annoying discussion topic which drove Goethe into hiding. In 1788 when Goethe had started the work, this was probably the first annoyance on his mind. By the time of the first printed version, in Schiller's Die Horen for 1795, the world had moved on, the French Revolution had begun in 1789, grinding the tectonic plates of feudal politics and society in Europe irrecoverably far apart. The events in France were so epochal that they demanded of every thinking person the taking of some stance.

Goethe, torn between the fatuous order of the self-serving butterflies of the Weimar court and the blood-soaked anarchic rage of the French mob (the wütende Gallier, 'the raging French') half-heartedly chose order – order and structure being key elements of his thought. His position was nuanced, but the raging times left no space for nuance. So, just as trivially with his escape from Werther, he telly us that he escaped from the issue in his flight to Rome.

But of course he didn't, for this is all after the fact, as we noted above. Once more we find a fantasist poet projecting some current concern onto a time six or seven years before. They are all liars, these poets –Plato and Nietzsche (among many others) told us so and with the title Dichtung und Wahrheit, 'Invention and Truth', Goethe himself said it. And we should believe him.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!