Cynthia's shade

Posted by Richard on UTC 2020-11-10 05:03

Sextus Propertius, Book IV, Elegy VII

We got to know that charming couple Sextus Propertius and Cynthia a couple of years ago, in a piece full of drunken debauchery, dented goblets and shattered crockery. Propertius' elegies detailing the highs and lows of their time together created one of the great literary pairings, 'Propertius and Cynthia', that can stand alongside 'Catullus and Lesbia' and 'Tibullus and Delia'.

In Elegy VII in Book 4 of his elegies, Propertius closed the relationship off with a tale of a nocturnal visit to him by the ghost of the newly buried Cynthia. In your author's opinion Elegy VII is a remarkable character study, masquerading as yet another love elegy. The character study is remarkable because of its psychological depths; depths that we moderns first understood only when the Austrian psychotherapists set about our psyches at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In this elegy Propertius gives us a portrait of Cynthia in all her human complexity. We encounter victimhood, viciousness, goading and taunting, all those things we met in their relationship when they were young and alive and throwing things at each other.

Nothing is as it seems, though: in Propertius' encounter with Cynthia's phantom, her shade and its words are the products of Propertius' imagination and his own complex feelings towards his ex-lover. This is a Browning poem written nearly two thousand years before Browning was born. We must never forget the artificer standing in the shadows behind his work, paring his fingernails. Almost nothing in this poem can be taken at its face value.

Before you begin

This article is not a scholarly gloss on the poem nor a critical text. The elegy has been split up into thematic sections, which also allows the notes and comments to stay close to the relevant passages in Latin and English. Occasional notes point to words and phrases of particular interest; each section is concluded by gloss with some additional comments.

The translation attempts to follow the Latin in a comprehensible manner: an absolutely literal translation would be almost unreadable; literary 'reconstructions' in modern idiomatic English are misleading. The only liberties we have taken are some changes in word order to cope with a declined language. The reader doesn't need to be able to read Latin: the English translation, the notes and the comments should be sufficient. The Latin is really only there to allow Latinist troublemakers to investigate the translation easily.

The text used is Lucian Mueller's edition of 1898 (Leipzig, Teubner), which has been chosen for its easy online availability in Perseus (NB: the last line of the poem is missing from the current Perseus implementation). Although this text lacks the subsequent century of scholarly effort it is good enough for our purposes of gaining a general understanding of Elegy 4.7. In disputed passages W.A. Camps edition of Propertius has generally been followed, in this case Book IV (1965, Cambridge University Press).

Cynthia appears

Sunt aliquid Manes: letum non omnia finit,

1luridaque euictos effugit umbra rogos.

Cynthia namque meo uisa est incumbere fulcro,

3murmur ad extremae nuper humata uiae,

cum mihi somnus ab exsequiis penderet amoris,

5et quererer lecti frigida regna mei.

There are such things as ghosts: death is not the end of everything, and somehow a pale shade can survive, escaping the pyre. Cynthia, namely, who had just been interred at the side of that busy road, appeared to me, leaning over my pillow, when, after the burial of her whom I had loved, sleep would not come to me as I lamented that that my bed was a cold and desolate domain.

Notes

Manes: Lewis and Short tells us that Manes are the 'deified souls of the departed, the ghosts or shades of the dead, the gods of the Lower World, infernal deities, manes (as benevolent spirits, opp. to larvae and lemures, malevolent spirits).' The question of whether the apparition is a ghost – that is, an object perceived or imagined by the conscious mind – or a figure in a dream is unresolvable and probably irrelevant to the classical mind. In line 87, Cynthia freely conflates dreams and the ghosts which wander around the world of humans in the night.

murmur ad extremae nuper humata uiae: Cynthia's grave was on the Via Tiburtina, a busy thoroughfare not far from the town of Tibur itself, where she lived.

nuper: 'recently' buried – but just how recently is unclear. The sense of the poem is that it was very recent, perhaps earlier on the same day that we find Propertius lying sleeplessly in his bed, 'after the burial of her whom I had loved'. Propertius and Cynthia seem to have split up some unspecified time before her death, for Cynthia mentions bitterly the existence of her successor in Propertius' affections. Various hints in the poem suggest that it was Propertius who left her.

regna: Propertius teases his reader with some creative ambiguity. [Camps 116] offers two equally possible readings: (a) 'and I grieved that my bed was a cold and desolate domain'; or (b) 'and I grieved that she who once reigned in my bed was now a cold and lifeless corpse'. The first reading, (a), is the one taken by most translators.

The second reading, (b), has some attractions, since it solves the problem of the cold bed: Propertius and Cynthia appear to have split up sometime before her death and we gather from later in the present elegy (at least according to Cynthia) that a new queen has already installed herself in Propertius' 'cold and desolate domain'. Perhaps propriety – what little of it the Augustan elegists possessed – may have kept Propertius' new squeeze out of his bed in the night immediately following Cynthia's obsequies.

As much as your author would like to take (b), he is constrained by pedantry: Cynthia was not a cold corpse by the time that Propertius has taken to his bed, she was a small heap of bones and ashes, probably still warm.

Commentary

Whether she is a ghost or a figure in a dream, Cynthia has the dominant position in this exchange, if only in terms of staging: she is standing at the head of his bed and bending over him. This is a recognition that nearly all of the elegy is devoted to the tirade she directs at Propertius. As we shall see, Propertius – or, more accurately, Propertius' persona – is a passive figure in the elegy and apparently counters none of her invective.

Cynthia's ghost

eosdem habuit secum quibus est elata capillos,

7eosdem oculos; lateri uestis adusta fuit,

et solitum digito beryllon adederat ignis,

9summaque Lethaeus triuerat ora liquor.

spirantisque animos et uocem misit: at illi

11pollicibus fragiles increpuere manus:

Her hair was arranged just as it was when she was carried to the pyre, her expression, too, was the same: her dress was charred down the side and the beryl, which she used to wear on her finger, had been also been scorched; her lips were still wet with the water of Lethe, but the mind and voice that emerged was as though still alive, as she snapped her slender fingers.

Notes

eosdem oculos: [Camps 116] suggests that oculos can be understood as '(facial) expression'. We have taken this reading because it solves the problem that 'eyes' would require Cynthia's eyes to have been open as she was being carried on her bier to the funeral pyre, which is where Propertius last saw her. It is extremely unlikely, however, that her eyes would have been left open on her bier.

summaque Lethaeus triuerat ora liquor: Some translators like to assign a meaning beyond simply 'wet' for the effect on her lips of the waters of Lethe, which the shades of the dead drink on their passage to Hades: 'withered by' or 'marked by'. The result is dramatic, but clearly not what Propertius intended – unlike her clothes and her ring, her spirit body itself has not been damaged on the pyre: see the discussion of this in the Commentary. Propertius' simple image of the moist lips of the ghost is much more poetic and quite sufficient.

It is also clear that for Propertius the river Lethe, from whose waters the shade of Cynthia has drunk, is not the river of forgetting; this attribute was not consistently applied in antiquity and fits in with nothing we read in the rest of the elegy. Despite the moist lips, the spectral Cynthia has all her faculties about her, as we shall see.

pollicibus fragiles increpuere manus: Given that some fire damage to inanimate objects is described in this section, translators often take a step too far with the description of Cynthia's hand or fingers. In fact fragiles only says that her hands were slender or delicate, nothing to do with fragile or brittle. She is snapping(!) her fingers using her thumb (pollicibus), a gesture still common in modern Italy, intended as a rebuke but more likely to gain someone's attention – that of a poet trying to get to sleep, for example.

Commentary

The appearance of the ghost is puzzling at first, but a careful reading solves all our difficulties. Propertius has already prepared us for her apparition in the second line of the elegy: 'somehow a pale shade can survive, escaping the pyre'. That is, the shade leaves the corpse before it is burnt on the pyre. The body of Cynthia's shade is therefore intact, though spectral.

Propertius' last memory of her is of her body on its way to the pyre and it is with this memory that her appearance as a ghost is being compared. We are told in line 29 that he did not follow her through the gate to the pyre and thus did not see her burning body. Her apparition in Propertius' dream sequence explicitly corresponds to his last sight of her.

Though Cynthia's spirit body may be intact, the poet in Propertius could not resist shocking his readers with some graphic details of her cremation: the dress charred down the side, the ring with the beryl stone scorched. The shade of Cynthia may have left her body before it was burnt, but we are shown the dramatic effect of the material things she wore partly damaged by the flames. The only trace of her passage to Hades is the wetness of Lethe upon her lips.

The sleeping lover

"perfide nec cuiquam melior sperande puellae,

13in te iam uires somnus habere potest?

iamne tibi exciderant uigilacis furta Suburae

15et mea nocturnis trita fenestra dolis?

per quam demisso quotiens tibi fune pependi,

17alterna ueniens in tua colla manu!

saepe Venus triuio commissa est, pectore mixto

19fecerunt tepidas pallia nostra uias.

foederis heu taciti, cuius fallacia uerba

21non audituri diripuere Noti.

You unfaithful one, of whom no girl can expect better, has sleep already overcome you? Have you forgotten so soon our secret escapades in sleepless Subura, my window-sill worn from nightly pranks? How often I have hung on the rope let down from the window, down which I climbed hand over hand to your neck? Venus was often invoked at the crossroads, with our breastbones entangled we warmed the road beneath. Our secret union of love, the deceitful words which the South Wind, not wishing to hear, has scattered.

Notes

uigilacis…Suburae: 'Restless' Subura was the district where Cynthia lived. It was a place known for its nightlife.

trita fenestra: It is not clear why Cynthia had to leave her house in the night via the window for her assignations with Propertius and so frequently (nightly) that the window-sill was damaged by the rope. Father? Lover? Husband?

Always a master of the telling image, Propertius describes her descending the rope, hand over hand, to land with some part of her anatomy on Propertius' neck.

Commentary

Cynthia accuses Propertius of choosing sleep over grief, an accusation which she then reinforces with a reminder of how things used to be in the early days of their love, when sleep was the last thing on their minds. The contrast between the bereaved Propertius, in his bed, anxious for sleep to come, and Propertius the one-time lover of Cynthia in those days of sleepless nights in Subura is forceful: Cynthia, a master of love's rhetoric. Oh, just a minute: Propertius is that master, currently putting words into the ghost's mouth.

In this section we begin to see the outlines of the elegy start to become clear: it is a character sketch of Cynthia, with all her faults: her temper, her viciousness, her way with devastating argument. We begin now to leave the pathos of her death and burial and enter a character study composed from her own words – or more accurately, the words that Propertius, her former lover, puts into her mouth.

The neglectful mourner; the abandoned lover

at mihi non oculos quisquam inclamauit euntis:

23unum impetrassem te reuocante diem:

nec crepuit fissa me propter harundine custos,

25laesit et obiectum tegula curta caput.

denique quis nostro curuum te funere uidit,

27atram quis lacrimis incaluisse togam?

si piguit portas ultra procedere, at illuc

29iussisses lectum lentius ire meum.

cur uentos non ipse rogis, ingrate, petisti?

31cur nardo flammae non oluere meae?

hoc etiam graue erat, nulla mercede hyacinthos

33inicere et fracto busta piare cado.

But no one called me to stay as the light left my eyes: I would have gained a day had you called me back. No watchman made noise around me with his cleft rod and a jagged tile shard wounded my exposed head. And anyway, who saw you at my funeral rites bowed with grief or wearing a black toga, wet with tears? If you couldn't bear to accompany me through the gate, at least you could have ordered my bier to be carried more slowly till then. Why did you not pray for winds to fan my pyre? Why did my flames not smell of fragrant oils? Was it too much expense for you to throw hyacinths upon me, which cost next to nothing? and to break a wine-jar, as piety demands, over the ashes of my pyre?

Notes

at mihi non oculos…reuocante diem: This distich refers to the superstition that at the moment of death, when 'the light left the eyes' those attending could exhort the dying one to come back with loud cries. The soul would then delay its departure for one more day on the earth.

nec crepuit fissa…custos: whilst the corpse was laid out awaiting burial it was customary to hire a watchman to remain with the body. He was equipped with a split cane or rattle in order to frighten evil spirits away.

laesit et…caput: The exact meaning of this line is a puzzle. The best guess is that Cynthia's head was supported by a piece of terracotta which either had a jagged edge or broke during the transport of her bier, gashing her head. Her ghost has nothing good to say about the funeral arrangements, which means that whatever it does refer to does not reflect well on Propertius. [Camps 118] suggests that the use of terracotta instead of a pillow was 'evidence of cheap arrangements'.

fracto busta piare cado: This refers to the custom of breaking a jar of wine over the bones left after burning, before they were put into the urn.

Commentary

After skewering Propertius for his impious attempt to sleep when he should really be grieving, Cynthia attacks him for his careless and even stingy attitude to her funeral. Whether any part of the tirade is true or not, its overall message is an expression of Cynthia's feeling that she has been abandoned by Propertius. As we shall see shortly, she and Propertius have been separated for a while and he seems to have already found a replacement.

We note once again the puzzling fact that Propertius is reproducing the bad things which Cynthia's ghost said about him – puzzling because superficially it seems an odd thing to do to give currency to all his supposed defects without making the slightest attempt to answer them.

We are being ensnared by Propertius the great artificer: through his black literary arts he is making us believe that Cynthia's ghost really did appear to him and really did produce a rhetorically artful monologue, which he then noted down and recast into an equally artful elegy.

Propertius may have written his poems with immortality in mind, but much more in his mind was the circle of friends and admirers among whom his work circulated. We can only assume – but it seems a reasonable assumption – that those who knew Cynthia would have found this passage eerily and perhaps humorously reminiscent of the deceased woman in full fishwife mode on the many character defects of her lover.

We should also touch on something here that we will discuss more extensively later. Propertius wrote her account of her cheapskate funeral and never tried to contradict it, because it really was cheapskate, which is what Propertius' is really telling us, with seemingly malicious pleasure.

Punishing Lygdamus and Nomas

Lygdamus uratur — candescat lamina uernae —

35sensi ego, cum insidiis pallida uina bibi —

at Nomas — arcanas tollat uersuta saliuas;

37dicet damnatas ignea testa manus.

Have Lygdamus tortured – let the branding blade be white-hot for that slave – I sensed the poison when I drank the wine that made me ill; and Nomas, the crafty one, may have hidden her secret poisons, but the hot stone will make her confess that her hands are guilty.

Notes

Lygdamus…Nomas: Lygdamus is one of the slaves in Propertius' household; Nomas, too, it seems. The suspicion that (older) women were masters of the black arts survived into modern times in the figure of the witch.

Commentary

Poisoning was in fashion throughout Roman times – at least the suspicion of poisoning, which, in the absence of secure medical diagnosis, was an easy accusation to make. Slaves had no rights as such and could be subjected without further ado to trial by torture.

It is a wild and shocking accusation, but not to be taken seriously. It is one more piece of Propertian evidence for the wild, vindictive anger of Cynthia. It is, however, preparing us for the conspiracy theory which she is about to present to Propertius.

The defects of her successor

quae modo per uilis inspecta est publica noctes,

39haec nunc aurata cyclade signat humum;

et grauiora rependit iniquis pensa quasillis,

41garrula de facie si qua locuta mea est;

nostraque quod Petale tulit ad monumenta coronas,

43codicis immundi uincula sentit anus;

caeditur et Lalage tortis suspensa capillis,

45per nomen quoniam est ausa rogare meum.

te patiente meae conflauit imaginis aurum,

47ardente e nostro dotem habitura rogo.

She whose long, golden dress leaves its marks on the ground was a common and cheap whore, who exposed herself to the public nightly; if a chattering maid speaks cheekily of my beauty she gives her a larger portion of wool in her basket to be spun; she had old Petale, who left a bouquet of flowers on my grave, chained to a filthy block of wood; Lalage is hung by her plaited hair and flogged, because she dared to ask a favour in my name. You let her melt down my gold image for her own benefit, so she can profit from my blazing pyre.

Notes

nostraque quod Petale…sentit anus: Most translators add causality to to the two clauses of this distich by adding some word such as 'because' or 'for'; that the ageing Petale was punished because she laid a wreath on Cynthia's grave. This causality is not only not there in the Latin, it creates a problem with the overall narrative of the elegy, since it appears to push back Cynthia's funeral for some time. This, in turn, brings into question our assumption that is was the very recent funeral which triggered Propertius' fitful sleep and the appearance of Cynthia's ghost by his bed, unless the punishment block was applied on the same day as the funeral took place.

ausa rogare: A slave would make a request to his or her master or mistress accompanied by the invocation of the name of an honoured third party, which in this particular case would be something like '[I beg/entreat you] in the name of Cynthia'.

te patiente meae conflauit…rogo: Propertius has very skilfully woven two images together: Cynthia's own fiery destruction and the destruction of her image by being melted down in the gold furnace. Both processes get rid of her, one physically, the other metaphorically. The imaginis aurum suggests an image in gold, such as might be found in a signet ring.

dotem: Taken strictly this word means 'dowry', but it can also be used in the much more general sense of a gift or even something profitable. The notion that Propertius is giving his new lover a ring for her dowry is absurd – that is not how dowries work – and we should take the word to mean 'for her own benefit/profit'.

Commentary

This section offers a coherent narrative, but is incomprehensible on its surface. As it stands, parataxis requires us to believe that Nomas, the witch, Cynthia's alleged poisoner, wears long expensive dresses and bosses around and persecutes either Propertius or even Cynthia's former slaves and maids. This is absurd. If the translator follows the Latin and simply writes 'she', the reader has very little chance of interpreting this section correctly.

The only way to make sense of this passage is to assume that the implicit 'she' is referring to the new girl in Propertius' heart. She is not named explicitly – whether because Cynthia will not dignify her with a name, or because Propertius has chosen not to drag his new lover by name into his satirical account of Cynthia's ragings. This section brings us the fury of the scorned lover, Cynthia, at her replacement, the unnamed 'cheap whore', who now revenges herself on anything or anyone associated with Cynthia, her predecessor.

At its heart, Cynthia's complaint is that her successor is attempting to purge all memory of Cynthia from Propertius' household, whether from the affections of the servants and slaves – whose devotion reflects well on Cynthia – or even from physical objects such as the gold ring bearing her image. She is also delivering evidence for the motive that led to her poisoning – in other words, the new girl caused it to happen: Lygdamus and Nomas were merely tools to this end.

Cynthia the faithful

non tamen insector, quamuis mereare, Properti:

49longa mea in libris regna fuere tuis.

iuro ego Fatorum nulli reuolubile carmen,

51tergeminusque canis sic mihi molle sonet,

me seruasse fidem. si fallo, uipera nostris

53sibilet in tumulis et super ossa cubet.

However I will not scold you, Propertius, however much you deserve it: in your poems I have reigned long. I swear by the song of the Fates, which no man can can unravel, and truly, that the three-headed dog may bark gently at me, that I have been faithful to you. If I lie, may a hissing viper nest on my burial mound and wind around my bones.

Notes

tergeminusque canis: The three-headed dog Cerberus, one of the guardians of the Underworld.

Commentary

Anyone who has read Propertius' many love elegies to Cynthia will be surprised at her claim that she has always been faithful. In fact, this statement should be read in the context of her preceding assertion, that she has 'reigned long' in his works.

In those works, fidelity is not a word that comes into the reader's mind in respect of either of these two lovebirds. The attentive reader will realise, after a moment's thought, that Propertius, who has invested so much literary capital in Cynthia's sexual treacheries, is extracting satire from the utterances of Cynthia's shade, who is brazenly prepared to swear by an assortment of eventualities that what she says is true.

Not only is it not true, but from everything we read in Propertius' Cynthia elegies, we can assume that Propertius has heard similar professions of fidelity from her lips many times before.

The treacherous and the virtuous women

nam gemina est sedes turpem sortita per amnem,

55turbaque diuersa remigat omnis aqua.

unda Clytaemestrae stuprum uehit altera, Cressae

57portat mentitae lignea monstra bouis.

ecce coronato pars altera rapta phaselo,

59mulcet ubi Elysias aura beata rosas,

qua numerosa fides, quaque aera rotunda Cybebes

61mitratisque sonant Lydia plectra choris.

Andromedeque et Hypermestre sine fraude maritae

63narrant historiae tempora nota suae:

haec sua maternis queritur liuere catenis

65bracchia nec meritas frigida saxa manus;

narrat Hypermestre magnum ausas esse sorores,

67in scelus hoc animum non ualuisse suum.

sic mortis lacrimis uitae sancimus amores:

69celo ego perfidiae crimina multa tuae.

Two locations exist beyond the grim river and the shades are ferried across the water in two different directions. One carries the adulteress Clytemnestra and the incestuous Cretan queen, who contrived the counterfeit of the wooden cow. But look, the other group is borne off in a garlanded boat, where a blessed breeze gently fans the roses of Elysium, where melodious strings sound, Cybele's cymbals, and Lydian lyres struck for the turbaned dance. Andromeda and Hypermestra, wives beyond reproach, glorious heroines, relate the famous dangers of their stories. Andromeda complains that her arms are bruised by chains she suffered on her mother's account and that her hands did not deserve to be fettered to the cold rocks; Hypermestra tells of the monstrous deed of her sisters and how her heart had not been hard enough for such a crime. Thus our tears in death try to heal the wounds love caused us while we lived: I conceal in silence your many sins of infidelity.

Notes

Clytaemestrae: Clytemnestra was the sister of Helen ('of Troy') and the wife of Agamemnon. During the ten long years when her husband was away commanding the Greek forces in the Trojan War she became the lover of Aegisthus. On his return from Troy, Agamemnon (and some of his followers) were ambushed and killed by Aegisthus (with some degree of assistance from Clytemnestra, depending on who is telling the story). Her betrayal went beyond adultery into the murder of her husband, a particularly heinous crime in the classical world. Her faithlessness can be contrasted with the enduring fidelity of Odysseus' wife, Penelope:

…There is no being more fell,

more bestial than a wife in such an action,

and what an action that one planned!

The murder of her husband and her lord.[…]

Not that I see a risk for you, Odysseus,

of death at your wife’s hands. She is too wise,

too clear-eyed, sees alternatives too well,

Robert Fitzgerald, Odyssey, 1961, p. 199. Greek: Odyssey 11:445f

Cressae: The 'Cretan woman' is Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos of Crete, who fell in love with the famous bull. She had a wooden effigy of a cow constructed and, concealed in that, was serviced by the animal. The result was the conception of the Minotaur, part man and part bull, who would by killed by Theseus.

Andromedeque et Hypermestre: After her mother Queen Cassiopeia's boastful vanity had caused Poseidon to send a sea monster to ravage the coast of Aethiopia, Andromeda was chained to a rock as a sacrifice to the monster. She was rescued by Perseus.

Hypermestra was one of the 50 Danaids who were forcibly married to the 50 sons of Aegyptus. Their father insisted that they kill their husbands on the wedding night. Hypermestra, wed to an accommodating man, refused to do this and was imprisoned in chains by her father.

Top: Floor mosaic showing Andromeda rescued by Perseus. The slain sea monster and the head of the slain Medusa, both looking unhappy. Image: mosaic in the 'House of Poseidon' in Zeugma, 2nd-3rd century AD, in the Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Gaziantep, Turkey.

Bottom: Fresco from the 'Casa Dei Dioscuri' (VI,9,6) showing Perseus and Andromeda. Andromeda is chained to the sea-cliff by one hand. Perseus is holding in his left hand the head of the Medusa. The body of the slain sea-monster can be seen at the lower left.

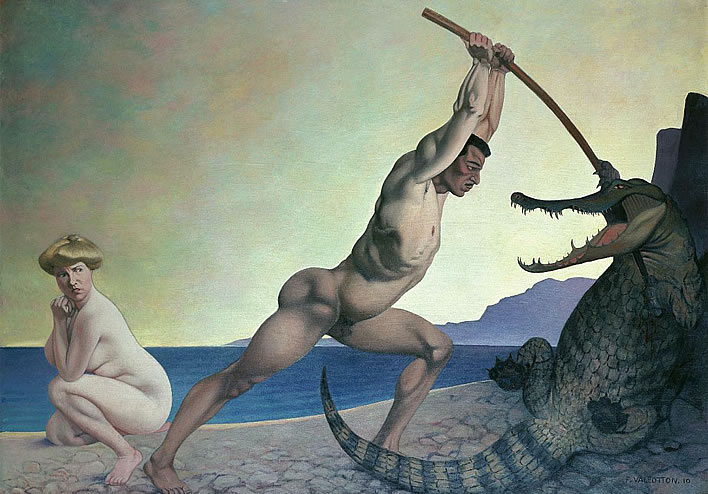

Two paintings on the Andromeda theme by the Swiss artist Félix Edouard Vallotton (1865-1925). The paintings are as ironic and satiric as our Propertian elegy.

Top: Andromède enchaînée / Andromeda in chains (1925). She is hiding her face in shame or fear or both, awaiting the sea monster.

Persée tuant le dragon / Perseus slaying the dragon (1910). On a literal level, the scene shows a placid seashore in a stylised background. It appears that the man and the woman were swimming and were surprised by a crocodile. The figures are anything but the beautiful shapes of tradition: the man is notable for his tan lines, neither of the figures lead a life without clothes. Excitable French commentators find the man's arms excitingly phallic and his bottom a thing of consummate beauty. The woman is wearing only a Belle Epoque hairdo and is, once more violating tradition, unchained. She is fond of the plaisir de la table. The satiric intention of the painting is clear and caused more than a small stir when it was first shown. But opinions as to exactly what that intention was vary widely.

Images: © 2020 - Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève / Ville de Genève, Musées d'art et d'histoire.

Commentary

The mythological tableau which Propertius has the shade of Cynthia conjure up is another step in Cynthia's depiction of her victimhood. In the previous section she swears that she was always true to Propertius; now she places herself in the boat carrying the virtuous women, who have suffered at the hands of others, to their pleasant eternity on the Elysian Fields. Her victimhood is given an extra twist when she tells Propertius, that unlike the other wronged women, she will keep her tales of Propertius' infamy to herself.

Remember: this account is entirely Propertius' concoction. That he shows us Cynthia being transported in the garlanded boat of the 'virtuous women' to a delightful afterlife in the Elysian fields – well, his male friends who knew her must have found this #metoo moment of victimhood a great joke. This is the women who a moment before was demanding that Propertius put his slaves to the torture on her behalf and who hurled invective at her former lover and her successor in his affections.

The bitterness which Cynthia's shade directs at Propertius is understandable when we consider that she was dumped by him: almost everything she (that is, Propertius) says paints her as the innocent victim of this heartless beast of a poet whom she so foolishly loved. We can therefore assume that Propertius had his reasons for ending the relationship.

In a love affair of such epic dimensions, full of turbulent and violent scenes, we can also assume that the dispute was not over domestic chores or who could have the remote control: the dispute would have been about infidelity – and not merely another one of the frequent excursions taken by both sides during this relationship. Cynthia must have had a fling which turned out to be intolerable for Propertius, which reduced his standing in his circle and among his intimates.

If to that we add the animus her ghost is shown directing towards the (presumably) faithful servants of Propertius' household, we may find a further reason for Propertius to hate her, perhaps a reason that became the tipping point at the end of their stormy relationship.

If we accept this, we now understand why so much of this elegy turns on fidelity: Cynthia's assertions of Propertius' wanderings and her extreme pleadings that she was always faithful to him, ending in her mock oath and the mythological scene of her joining the other wronged women loafing around and gossiping about themselves in the Elysian Fields. We remind ourselves yet again: Propertius wrote this, not Cynthia.

Cynthia's testament

sed tibi nunc mandata damus, si forte moueris,

71si te non totum Chloridos herba tenet:

nutrix in tremulis ne quid desideret annis

73Parthenie: potuit, nec tibi auara fuit.

deliciaeque meae Latris, cui nomen ab usu est,

75ne speculum dominae porrigat illa nouae.

et quoscumque meo fecisti nomine uersus,

77ure mihi: laudes desine habere meas.

pelle hederam tumulo, mihi quae praegnante corymbo

79mollia contortis alligat ossa comis.

ramosis Anio qua pomifer incubat aruis,

81et numquam Herculeo numine pallet ebur,

hic carmen media dignum me scribe columna,

83sed breue, quod currens uector ab urbe legat:

HIC TIBVRTINA IACET AVREA CYNTHIA TERRA:

85ACCESSIT RIPAE LAVS, ANIENE, TVAE.

But now I give you instructions, if by any chance you are moved, in that Chloris' potions have not completely bewitched you: let my nurse Parthenie lack nothing in her trembling old age: she did not use her position to profit from you; and let not my dear Latris, named for her faithful service, hold the mirror for another mistress. As for the poems you composed in my honour, I bid you burn them: win praise through me no longer. Plant ivy on my grave, so that its swelling tendrils may gently bind my delicate bones with intertwining leaves. Where fruitful Anio irrigates full-branched orchards and where, by the grace of Hercules, ivory never loses its brightness, there in good view on a pillar inscribe an epitaph that is worthy of me, but also brief, that the traveller may read it as he hastens from Rome: HERE IN TIBUR'S SOIL LIES GOLDEN CYNTHIA: YOUR BANK, ANIO, HAS GAINED NEW GLORY.

Notes

Chloridos herba: Chloris may be the name of Cynthia's successor, but this seems unlikely, since Propertius wisely went out of his way not to name her explicitly when he had the chance in lines 39f.

Chloris may be another witch, much like Nomas, who, in the service of the anonymous successor, has manipulated Propertius affections towards the new girl. Given the wild ravings which Propertius has put into the mouth of Cynthia's ghost so far, we would be justified in doubting whether this 'Chloris' even existed; or we may be uncomprehending parties to an in-joke among Propertius' circle.

Once again we have to remind ourselves that the speech of Cynthia's ghost is really Propertius' speech. We also have to remind ourselves how deep our ignorance really is about much of this elegy, if we have no way of resolving this crucial point. Textual exegesis will only take you so far; it will not replace the contextual knowledge of the members of Propertius' circle who read this elegy.

Latris, cui nomen ab usu est: λάτρις, 'Latris' is the Greek term for a servant; her name therefore is the same as her function in Greek. That she 'held the mirror' for her mistress means that she was Cynthia's personal maid.

laudes desine habere meas: this laconic phrase leaves much unsaid, meaning that its translation requires some imagination. [Camps 123] suggests two possible expansions: 'either (a) "keep no more the poems that you wrote in my praise"; or (b) "boast no more of your possession of me"'. Your author takes (b) as being on the right track, since it aligns with the ghost's egomaniacal claim to have 'reigned long' in Propertius poetry in line 50, thus transferring most of the credit for said poetry from the poet to her.

hic carmen media…ANIENE, TVAE: In these lines, following on from her egomania about his verses, we feel the full force of Propertius' mockery of his dumped mistress. Cynthia has no claim to fame apart from her presence in Propertius' love elegies.

As far as her burial is concerned, Propertius tells us in line 4 that it was murmur ad extremae nuper humata uiae 'at the side of that busy road'. As a nonentity, a mound at the side of a noisy road is really the best she can hope for. Nevertheless, Propertius gives us her own imaginings – or, more accurately, the imaginings he has put into the mouth of her imagined ghost. The best word to describe the ghost's ravings on the subject of her grave and memorial is 'bombastic'.

Cynthia the nonentity is not content with a gravestone or a tablet inscription beside the busy road, she demands an (expensive) column, with an inscription half way up it so that it can be read from the busy road, containing an 'epitaph that is worthy of me'. In her suggested inscription she styles herself as AVREA CYNTHIA, 'golden Cynthia', a nonentity who has now, for some incomprehensible reason, brought glory to that bank of the Anio.

In this scene, Propertius gives her both barrels of his satirical shotgun. What malicious pleasure the writing of those lines must have given him! How his friends would have laughed to read his final takedown of that hysterical strumpet!

Commentary

In the notes, we have addressed the ferocious satire of the words Propertius put into the mouth of Cynthia's ghost concerning her wish for a monument that is 'worthy' of her. We might say that lines 83-86 represent the real monument that Propertius has raised to her, a monument of mockery.

Also, when we read lines 23-34, in which Propertius allows Cynthia's ghost to describe the many defects of her cheap funeral, we found it interesting that Propertius made no attempt to counter the ghost's (i.e. Propertius') representation of that event. We now realise that he made no attempt to refute the complaints he put into the mouth of the ghost because they were indeed completely true.

It is clear that, if Cynthia had a scrappy send off, that was, in Propertius' opinion, only what she deserved after the egregious betrayal of him that must have caused their final separation. No matter how cheap a pillow, a nightwatchman and some scattered hyacinths may have been, he was not going to spend anything on the burial of this woman who had so wronged him.

The two gates of dreams

nec tu sperne piis uenientia somnia portis:

87cum pia uenerunt somnia, pondus habent.

nocte uagae ferimur, nox clausas liberat umbras,

89errat et abiecta Cerberus ipse sera.

luce iubent leges Lethaea ad stagna reuerti:

91nos uehimur, uectum nauta recenset onus.

nunc te possideant aliae: mox sola tenebo:

93mecum eris, et mixtis ossibus ossa teram."

Don't reject the dreams which emerge from the Gate of Truth: when such dreams come they have weight. In the night we wander around; night frees imprisoned shades and Cerberus himself wanders about, his tether loosed. The law compels us at dawn to return to Lethe's waters, we are transported back, the ferryman counts the load. Others may possess you now: but soon I will have you for me alone. You will be with me and our shades will embrace tightly.

Notes

piis uenientia somnia portis: the 'gate of truth' or 'gate of fidelity'. Propertius is alluding to either Odyssey 19:562f and/or its pale shade Aeneid 6:894. Here is the Homeric version, in the translation of Robert Fitzgerald (1961):

Penelope shook her head and answered:

'Friend,

many and many a dream is mere confusion,

a cobweb of no consequence at all.

Two gates for ghostly dreams there are: one gateway

of honest horn, and one of ivory.

Issuing by the ivory gate are dreams

of glimmering illusion, fantasies,

but those that come through solid polished horn

may be borne out, if mortals only know them.

I doubt it came by horn, my fearful dream—

too good to be true, that, for my son and me.

Commentary

On the surface, the break between this section and its predecessor is puzzlingly abrupt.

After giving Propertius fanciful instructions for her monument, Cynthia's ghost now discusses the shades that walk the earth in the night and visit the living in dreams.

At the start of our reading of this elegy we noted the ambiguous nature of the classical conception of the 'ghost', which mixes up our modern differentiation between ghosts as independent objects that can be seen when we are awake, as opposed to the phantoms that haunt our dreams – and only 'exist' within them. The present section epitomises that ambiguity, in that the apparitions of dreams also walk around the physical world.

According to Cynthia's ghost (that is, the words Propertius puts into her mouth), the dreams these ghosts bring contain truths and are to be taken seriously. Even Cerberus, the monstrous three-headed dog which guards the entrance to Hades, can slip the iron bar which holds him and also wander among the living during the night, although it is not clear what bearing this particular horror has on the issue at hand.

Cynthia seems to be implying that her phantom has sprung from the Gate of Truth, but Propertius follows up this statement only with examples of hideous things, now 'free' to wander in the darkness, suggesting that Cynthia's dream phantom has not spring from the 'Gate of Truth' (=the 'Gate of Horn') at all but from the other gate, which Cynthia doesn't name explicitly but which Penelope called the 'Gate of Ivory', the gate from which come merely glimmering allusions, fantasies. We get the impression that Cynthia is hinting that her former lover – that faithless swine – is going to receive more than his fair share of such nocturnal visits.

In the section describing the boat of virtuous women on their way to the Elysian Fields (lines 55f.) we mentioned in passing Odysseus' wife Penelope as the true model of the virtuous and faithful woman. Now we find Propertius explicitly alluding to a speech of hers, in which she described the two gates by which dreams exit.

Even more telling, this speech is made by Penelope during a dialogue with her (still unrecognised) husband Odysseus. We are on the brink of the dramatic reunion between the ultra faithful Penelope, who engaged in ruses to keep her suitors at bay during the twenty years her husband was absent, and her husband, who endured so many trials and catastrophes, just to get back to her and his kingdom. Odysseus may have had his sexual encounters during his wanderings, but his underlying fidelity cannot be disputed.

Joseph Wright of Derby, Penelope Unravelling Her Web, 1783-1784. Penelope unravelling by night the web she wove during the day. Its completion would mark her readiness to accept one of the suitors infesting the palace; Odysseus' son Telemachus is sleeping; Argos, the faithful dog that lived just long enough to recognise Odysseus on his return, is sitting patiently.

Penelope's term, the Gate of Ivory, causes us to recall line 82, which refers to Cynthia's wish for her burial place in a locality where 'ivory never loses its brightness'. In that context the reference to ivory was no more than a puzzling aside: what does that mean? we asked ourselves, what does it have to do with the matter at hand?. Now we find Propertius invoking the speech of Penelope about the deceptive and malignant dream ghosts who emanate from the 'Ivory Gate'.

The speech of Cynthia's ghost, taken as a whole, certainly matches Penelope's description of such dreams as 'mere confusion, a cobweb of no consequence at all … glimmering illusion, fantasies'.

In Book 11 of the Odyssey, Odysseus summons up from Hades the shades of the dead. Some of these – Elpenor, Tiresias, his mother, Agamemnon etc. – are worth his conversation, can add to the great knower's stock of knowledge, but the whispering crowd of other shades which approach him he keeps from drinking the blood that would give them the power of speech. In effect, he is the gatekeeper who selects the shades that should pass through the Gate of Horn, the Gate of Truth.

Cynthia's ghost concludes with one final perceived triumph over her unnamed successor – and any successors that may follow her: she and Propertius will be reunited in death, strangely not as shades, but as tightly intertwined or intermixed bones. We recall that in an earlier section she also ordered that ivy be planted on her grave, the roots of which would wrap around her bones gently.

[Camps 125] suggests that ossa, 'bones' is being used here as a metonym for 'shade'. This is an attractive reading, given that the passage is already full of shades in the afterworld and that Cynthia's vision of her eternal life with her poet must refer to a union of their shades, not some dusty old bones. Camps also points out the odd metonymy in line 19: pectore mixto, 'breastbones entangled'. However, he admits that we are probably stuck with the more immediate literal reading: 'bones'. Your author has fewer scruples, since taking the metonym of 'bones' for 'shade' also allows us a sensible reading of the otherwise completely puzzling final distich.

Cynthia's departure

haec postquam querula mecum sub lite peregit,

95inter complexus excidit umbra meos.

After her shade had ended this querulous encounter, it vanished, slipping away from my embrace.

Commentary

On a superficial reading, the final distich leaves us baffled. After all this bitter complaining, all the horrible things her ghost has said about him, which he has reported in a manner we can only take as harsh satire, why is he attempting an embrace at all?

The answer to this is that Propertius is responding to the last statement made by the ghost of Cynthia (=Propertius): 'You will be with me and our shades [bones] will embrace tightly'. In the present distich, Propertius has just refuted that proposition with an empirical test and discovered that no embrace is possible.

As Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) would put it around 17 centuries later: 'The grave's a fine and private place, / But none, I think, do there embrace.' Life is for the living, not the impotent dead.

The ghost has failed the test of its veracity – its message is 'mere confusion, a cobweb of no consequence at all … glimmering illusion, fantasies'. It is an escapee from the Gate of Ivory, not the Gate of Horn.

Readers have to get up early in the morning – very early – to stay ahead of these clever Augustan elegists, clever but faithless alley cats, the lot of 'em.

Summa summarum: This elegy is not a eulogy to a deceased love, but an act of satirical retribution by a wronged poet on an unfaithful woman.

Unfinished business

A long time ago – or so it seems now – we wrote that this elegy 'closed the relationship off'. The reader who now moves on to the next elegy in the collection, Elegy VIII, is in for a surprise: here are Propertius and his Cynthia, very much alive and shouting and kicking, just like the good old days, just as though nothing had happened.

Just as we showed in the case of Catullus and his Lesbia, the conventional order of poems in many of these classical collections is irredeemably corrupt. In defence of this sequence of elegies scholars argue that Propertius may have just been recalling an incident from his time with the late Cynthia, just omitting to tell us that she was then dead.

Nevertheless, readers are understandably disconcerted when, after supposedly burying her in VII, he now in VIII treats us to an incident in their life together, an incident that reflects badly on both of them.

Was the ghostly encounter just a satirical joke? Did she die at all? The simple response to this philological bedlam is to assume that, as in the case of Catullus, the order of poems in the current collection is not chronological, that Cynthia did die and was buried and that Elegy VII is indeed Propertius' response to that event. In other words, Elegy VIII should come somewhere before Elegy VII.

Where that somewhere should be is another matter. Down the centuries scholars have shuffled the order of his poems around on the basis of no solid evidence at all. The current sequence is a weary acceptance of ignorance – 'that's how it is' – the only value of which is that it allows us to refer to the individual elegies in consistent ways. A long essay could be written on this theme, but a jumble remains a jumble, however lengthily you write about it.

It is a pity that after centuries of scholarship such corruptions are still challenging modern readers, but the individual poems of Propertius, a clever writer who can hold his poet's head high in the company of the great moderns, offer the reader their own rewards when read attentively.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!