Best Beloved

Posted by Richard on UTC 2025-07-27 18:14

In a recent article I took a close look at J.R.R. Tolkien's tale, The Hobbit (1937). There is a lot of greatness in the story, but there are also flaws, one or two of which are quite serious.

The most serious seemed to me to be Tolkien's irritating habit of inserting explanatory asides into the narrative, a habit to which at least two of his children, like me, took a strong dislike. Tolkien put this error down to his use of 'bad models'. I suggested that a good model would have been Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), whose Jungle Book (1894) and Puck of Pook's Hill (1906) have delighted adults and children for more than a century.

One of the rewards of writing a website like Figures of Speech is that sooner or later someone comes along and sets about something I have written. So it was in this case, when reader djc left a comment pointing out Kipling's use of asides – particularly the form of address 'Best Beloved' – in his story collection Just So stories (1902).

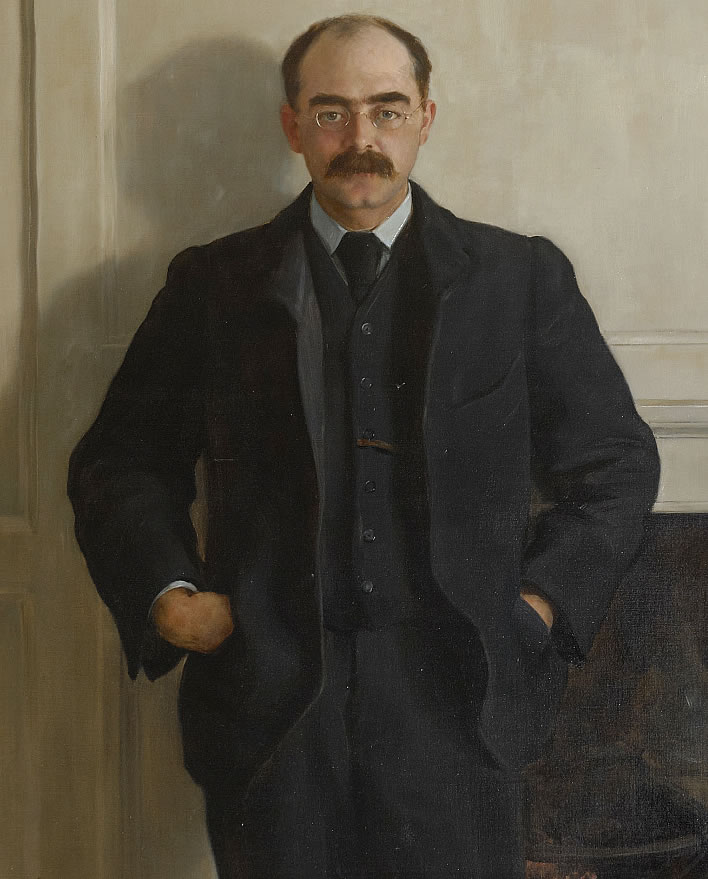

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) by The Hon. John Collier (1850-1934), 1900. Image: ©National Trust Images/John Hammond

I had never read the Just So stories, but when I did I found that the asides therein – and 'Best Beloved' in particular – didn't disrupt my reading at all, certainly not to the degree that Tolkien's ramblings in The Hobbit did.

Why was that?

Let's have a look at the first story in the collection, 'How the Whale Got His Throat', which, if you don't know the Just So Stories, will give you a flavour of the work. I have added a few notes explaining obscurities and reformatted the text to emphasis its semantic structures. The asides to the listener/reader 'Best Beloved' and others, are highlighted in green marker.

How the Whale Got His Throat

In the sea, once upon a time, O my Best Beloved, there was a Whale, and he ate fishes.

He ate the starfish and the garfish,

and the crab and the dab,

and the plaice and the dace,

and the skate and his mate,

and the mackereel and the pickereel, and the really truly twirly-whirly eel.

All the fishes he could find in all the sea he ate with his mouth—so! Till at last there was only one small fish left in all the sea, and he was a small 'Stute[1] Fish, and he swam a little behind the Whale's right ear, so as to be out of harm's way. Then the Whale stood up on his tail and said, 'I'm hungry.' And the small 'Stute Fish said in a small 'stute voice, 'Noble and generous Cetacean[2], have you ever tasted Man?'

'No,' said the Whale. 'What is it like?'

'Nice,' said the small 'Stute Fish. 'Nice but nubbly[3].'

'Then fetch me some,' said the Whale, and he made the sea froth up with his tail.

'One at a time is enough,' said the 'Stute Fish. 'If you swim to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West[4] (that is magic), you will find, sitting on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing on but a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders[5] (you must not forget the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, one shipwrecked Mariner, who, it is only fair to tell you, is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity[6].'

So the Whale swam and swam to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West, as fast as he could swim, and on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing to wear except a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders (you must particularly remember the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, he found one single, solitary shipwrecked Mariner, trailing his toes in the water. (He had his mummy's leave to paddle, or else he would never have done it, because he was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.)

Then the Whale opened his mouth back and back and back till it nearly touched his tail, and he swallowed the shipwrecked Mariner, and the raft he was sitting on, and his blue canvas breeches, and the suspenders (which you must not forget), and the jack-knife — He swallowed them all down into his warm, dark, inside cupboards, and then he smacked his lips — so, and turned round three times on his tail.

But as soon as the Mariner, who was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity, found himself truly inside the Whale's warm, dark, inside cupboards,

he stumped and he jumped

and he thumped and he bumped,

and he pranced and he danced,

and he banged and he clanged,

and he hit and he bit,

and he leaped and he creeped,

and he prowled and he howled,

and he hopped and he dropped,

and he cried and he sighed,

and he crawled and he bawled,

and he stepped and he lepped,

and he danced hornpipes where he shouldn't, and the Whale felt most unhappy indeed. (Have you forgotten the suspenders?)

So he said to the 'Stute Fish, 'This man is very nubbly, and besides he is making me hiccough. What shall I do?'

'Tell him to come out,' said the 'Stute Fish.

So the Whale called down his own throat to the shipwrecked Mariner, 'Come out and behave yourself. I've got the hiccoughs.'

'Nay, nay!' said the Mariner. 'Not so, but far otherwise. Take me to my natal-shore and the white-cliffs-of-Albion, and I'll think about it.' And he began to dance more than ever.

'You had better take him home,' said the 'Stute Fish to the Whale. 'I ought to have warned you that he is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.'

So the Whale swam and swam and swam, with both flippers and his tail, as hard as he could for the hiccoughs; and at last he saw the Mariner's natal-shore and the white-cliffs-of-Albion, and he rushed halfway up the beach, and opened his mouth wide and wide and wide, and said, 'Change here for Winchester, Ashuelot, Nashua, Keene, and stations on the Fitchburg Road[7];' and just as he said 'Fitch' the Mariner walked out of his mouth. But while the Whale had been swimming, the Mariner, who was indeed a person of infinite-resource-and-sagacity, had taken his jack-knife and cut up the raft into a little square grating all running crisscross, and he had tied it firm with his suspenders (now you know why you were not to forget the suspenders!), and he dragged that grating good and tight into the Whale's throat, and there it stuck! Then he recited the following Sloka[8], which, as you have not heard it, I will now proceed to relate—

By means of a grating

I have stopped your ating.

For the Mariner he was also an Hi-ber-ni-an. And he stepped out on the shingle, and went home to his mother, who had given him leave to trail his toes in the water; and he married and lived happily ever afterward. So did the Whale. But from that day on, the grating in his throat, which he could neither cough up nor swallow down, prevented him eating anything except very, very small fish; and that is the reason why whales nowadays never eat men or boys or little girls.

The small 'Stute Fish went and hid himself in the mud under the Doorsills of the Equator. He was afraid that the Whale might be angry with him.

The Sailor took the jack-knife home. He was wearing the blue canvas breeches when he walked out on the shingle. The suspenders were left behind, you see, to tie the grating with; and that is the end of that tale.

Notes on 'How the Whale Got His Throat'

- ^ [a]stute.

- ^ Cetacean, aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises.

- ^ 'Nubbly' is not as you might think a 'childish' word made up by Kipling. It has an OED entry all of its own: 'Having numerous small protuberances; knobby, lumpy. Esp. of a garment or fabric: rough-textured; having slubs or knots. Also in extended use. Cf. knubbly adj. (1829)'. When you think about it, nubbly is actual quite a good description of a human being from the viewpoint of a hydrodynamically streamlined fish.

-

^

50°N 40°W are the coordinates for a location which is around the midpoint of the North Atlantic, between the westernmost point in Cornwall and the easternmost point of Canada/USA. It is on or near the Great Circle routes that passenger ships would take (the wreck of the Titanic is not very far away). Nowadays, when passenger ships (for transport, not just cruising around) have almost disappeared and GPS navigation has taken the guesswork out of nautical travel, we have forgotten the challenges of sailing over ocean wildernesses that made a waypoint such as 50°N 40°W seem 'magic'. Kipling appends an amusingly Kiplingesque poem in explanation:

When the cabin port-holes are dark and green

Because of the seas outside;

When the ship goes wop (with a wiggle between)

And the steward falls into the soup-tureen,

And the trunks begin to slide;

When Nursey lies on the floor in a heap,

And Mummy tells you to let her sleep,

And you aren't waked or washed or dressed,

Why, then you will know (if you haven't guessed)

You're 'Fifty North and Forty West!' - ^ 'Suspenders' are US English; British English is 'braces'. Rudyard married an American, Carrie Balestier, in 1892 and they settled down in Vermont. It is interesting to find him adapting himself to their chosen country so wholeheartedly. Effie was born in the USA in December, 1892. The family returned to Britain in 1896.

- ^ Kipling applies an epithet to the Mariner that is surely referencing Homer's famous description of Odysseus: πολύμητις (polumetis), 'strategist, many counsels'; πολύτροπος (polytropos), 'much travelled'; πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω (pollon d'anthropon iden astea kai noon elno), 'knowing the ideas and customs of many people': ' Tell me, O Muse, of the man of many devices, who wandered full many ways after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy. Many were the men whose cities he saw and whose mind he learned'. Unfortunately no goddess is around to rescue the Mariner and he is swallowed by the whale – so that he is now transformed into the Biblical Jonah.

- ^ The place names here are station names on various railway lines in north-eastern USA, in the region where the Kiplings had resettled. Fitchburg [Rail-]Road is the name of a railway line which runs between Fitchburg and Boston.

- ^ A sloka is a Sanskrit verse containing a proverb, maxim or saying. The couplet given here is not in the metrical form of the standard sloka – it would be quite a surprise if it were. Kipling gets himself out of rhyming 'grating' with 'ating' by adding that the sailor was Irish ('Hibernian').

This is the picture of the Whale swallowing the Mariner with his infinite-resource-and-sagacity, and the raft and the jack-knife and his suspenders, which you must not forget. The buttony-things are the Mariner's suspenders, and you can see the knife close by them. He is sitting on the raft, but it has tilted up sideways, so you don't see much of it. The whity thing by the Mariner's left hand is a piece of wood that he was trying to row the raft with when the Whale came along. The piece of wood is called the jaws-of-a-gaff. The Mariner left it outside when he went in. The Whale's name was Smiler, and the Mariner was called Mr. Henry Albert Bivvens, A. B. The little 'Stute Fish is hiding under the Whale's tummy, or else I would have drawn him. The reason that the sea looks so ooshy-skooshy is because the Whale is sucking it all into his mouth so as to suck in Mr. Henry Albert Bivvens and the raft and the jack-knife and the suspenders. You must never forget the suspenders.

Here is the Whale looking for the little 'Stute Fish, who is hiding under the Doorsills of the Equator. The little 'Stute Fish's name was Pingle. He is hiding among the roots of the big seaweed that grows in front of the Doors of the Equator. I have drawn the Doors of the Equator. They are shut. They are always kept shut, because a door ought always to be kept shut. The ropy-thing right across is the Equator itself; and the things that look like rocks are the two giants Moar and Koar, that keep the Equator in order. They drew the shadow-pictures on the doors of the Equator, and they carved all those twisty fishes under the Doors. The beaky-fish are called beaked Dolphins, and the other fish with the queer heads are called Hammer-headed Sharks. The Whale never found the little 'Stute Fish till he got over his temper, and then they became good friends again.

Suspending disbelief

The reader of The Hobbit is, from the very first to the very last line, required to suspend disbelief. We all know that there are no such creatures as hobbits, wizards, trolls, dewarves, goblins and elves. We all know that none of the locations mentioned in the book exists and we know that, regardless of how many maps the author may draw. The well-told tale interests us, captures us and draws us in; the satisfaction is such that we gladly suspend disbelief. To that we can add its scope, its epic qualities and its moral undertone.

Suspending disbelief is easier if the characters and locations in the work are plausible and might at sometime have existed. There are people (I have known a few) who cannot be doing with opera or musicals, particularly where characters burst into song on their deathbeds (La traviata, La bohème) or from within a sack (Rigoletto).

But if the tale captures us, we dispense gladly with the rational world.

Which is the key problem for The Hobbit. Just as we are settling down into the adventure of hobbits, wizards and dwarves, the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon interrupts to explain something to us. As Tolkien himself came to realise, doing this breaks the spell of our suspended disbelief – in his terminology the interruption drags us out of the Secondary World, the world of the story, and returns us to the Primary World, in which we are reading from the book.

The Hobbit is a printed story in a book. You can read it to a child, but in most cases the child who can cope with the subtleties of the tale will probably want to read the book for themselves. Tolkien claims that he read the book to two of his children, which may be sort of true for a short while, but this strikes me as implausible for a book that covers 270 compactly printed pages. It's really not a reading-to-children book.

Josephine 'Effie' Kipling, ND. Image:

If now we pick up Kipling's Just So stories, we realise immediately that this is a very different animal to The Hobbit. On the cover of the first edition (1902) the title is given as Just So Stories. On the title page, however, there is an important addition: Just So Stories / For Little Children. 'Little Children' means 'too young to read books' or 'stories for little children to listen to'. The collection of stories got its name 'Just So' because Josephine ('Effie') Kipling (1892-1899) insisted that they be read to her 'just so', that is, without any variation at every reading. This tells us that the book, 'For Little Children' was intended as a book for reading aloud – it was, in fact, a script.

Rudyard Kipling telling stories to some children on board a vessel bound for South Africa 1902 Image: © National Trust / Charles Thomas

Celia Catlett Anderson in 1982 wrote a paper in the Children's Literature Association Quarterly pointing out what she called 'Kipling's Reading Instructions in the Just So Stories'. Our interpretation that the stories are effectively scripts is borne out by her analysis:

Kipling uses tricks from the story-telling tradition (set phrases, asides to the reader, heavy repetition), poetic devices (refrains, rhyme, alliteration), and typographical clues to retain the tone and emphasis that he favored when telling the stories orally.

Anderson, Celia Catlett. '"O Best Beloved": Kipling's Reading Instructions in the Just So Stories.' Children's Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 1982, pp. 33-39. Project Muse / Johns Hopkins University Press

Why is this so significant?

Because in such a reading situation, there are no more Primary or Secondary Worlds. There is only a single, shared world of speaker and listener. Asides that are so disturbing in The Hobbit are in Just So no longer asides: they are just part of the coherent, continuous flow spoken by the narrator.

There is a little more to it, though. The stories being told in Just So are so… bonkers (I can think of no better word) that a suspension of disbelief is barely possible. Compared with a shipwrecked Mariner wearing only a pair of blue canvas breeches held up with braces and carrying only a jack-knife on a raft in the North Atlantic, a petit bourgeois hobbit seems rather everyday.

What propels the listener's interest in Kipling's tale is not some version of reality but a narrative sequence of ever wackier events and actions that are anything but real. An obvious comparison is with Edward Lear's nonsense poem The Owl and the Pussy-Cat (1870).

Put another way, in The Hobbit, Tolkien is attempting to construct an alternative reality (Tolkien's Secondary World) which demands the total suspension of disbelief to maintain its fantasy. Thus it is particularly vulnerable when asides break that suspension of disbelief by bringing the reader back to the Primary World.

In contrast, Kipling's narrative – let's call it a stream of consciousness – entertains the child with one wacky and amusing moment after another. No disbelief needs to be suspended, because no child believes a word of it anyway – they just enjoy the silliness.

Elevated nonsense

Kipling's verbal fireworks may be nonsense, but they are really quite high-level nonsense. The understanding and appreciation of the jovial madness of the tales requires a linguistic and literary sophistication on the part of the young listener. Josephine Kipling, 'Effie', Kipling's muse for this work, died of pneumonia when she was six. Kipling takes no prisoners in the intellectual demands this work makes on Effie and the 'Little Children' for whom it is intended.

The vocabulary, for example, is surprisingly advanced: the names of various fish, the ''Stute Fish', the 'Cetacean', 'latitude and longitude', 'infinite-resource', 'sagacity', 'natal-shore', the 'white-cliffs-of-Albion', a 'sloka', an 'Hi-ber-ni-an'. Even more interesting are the jokey or not-quite-real words and phrases which pop up: 'inside cupboards', the nonsense word 'lepped' which fits the rhyme scheme better than 'leapt', the clever joke, 'ating', ('eating' as spoken by an Irishman). This book may be subtitled 'for little children', but it is uncompromising in its linguistic demands.

Every child will enjoy the wonderfully subversive, po-faced irony of '…trailing his toes in the water. (He had his mummy's leave to paddle, or else he would never have done it…)'. In the end the Mariner 'went home to his mother' and we are reminded that she 'had given him leave to trail his toes in the water'; parental permission – to be given leave to do something – being an important factor in every child's life, as well as an adult mariner's.

Modern education practice expects modern children's books to contain language that is appropriate and familiar to the child. The theory sounds reasonable enough, but if children only meet words they already know, their vocabulary will never expand. In contrast, after a child has got through the twelve (or thirteen) Just So Stories, his or her language horizon will have been extended substantially. [Shortly after I wrote this a piece by the author Philip Womack appeared in The Spectator grumbling about the reduced vocabulary in modern children's books.]

Effie, Rudyard's muse

Let's face it,what a child gets out of a story such as this is not the narrative, but the close companionship of the reading adult. The Just So Stories got their name because Effie insisted that Rudyard tell her the story 'just so', exactly as he had done on the previous telling.

From this we can infer that the same story was told multiple times. There was nothing in the story that she had not already heard, but that is not the point, she knew it all backwards anyway, so much so that she would spot the slightest deviation, open her eyes and demand a correction. Rudyard had to write the stories down and read them to her in order to put an end to improvisation.

But what really mattered to her was that her Papa took the time to tell her a bedtime story that served as a bond between them: it was shared time of the best kind. She did not need constant innovation – just the opposite, in fact: like most children, she needed continuity and security.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!