The Odyssean shipwreck

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-08-15 07:43 Updated on UTC 2023-05-25

The shipwreck theme is based on a passage in Book 5 of the Odyssey. In 1938, in Guide to Kulchur, Pound praised the narrative qualities of the Odyssey, singling out the shipwreck episode for particular mention:

The Homeric world, very human. The Odyssey high water mark for the adventure story, as for example Odysseus on the spar after shipwreck. Sam Smiles never got any further in preaching self-reliance. A world of irresponsible gods, a very high society without recognizable morals, the individual responsible to himself. [GK:38]

He's right. Let's read the relevant parts of the original tale before confronting Pound's reworking. Fitzgerald's excellent translation maintains the pace and brings over the drama of the original.

Kalypso's sea-cave

Odysseus has had many adventures since he left Troy after it had been sacked by the Greeks in the Trojan Wars. He has lost all his crew and he has been an unwilling but dutiful guest of the nymph Kalypso for the last seven years. We are told that he spends the days gazing out to sea and weeping, only wanting to return to his distant home and family. Despite this misery, every night Kalypso's enchantment brings him to her bed, an excuse that married men caught in flagrante have been using ever since (about two and a half thousand years).[1]

Athena, Odysseus' divine protector, successfully intercedes with Zeus. Hermes, the messenger of the gods, is sent to Kalypso to tell her to release Odysseus and let the poor man go home.

Given our previous mention of the sea-caves of goddesses let us start with the account of Hermes' arrival at the cave of Kalypso – 'smoothwalled' and 'wide', not just some hole in the rock.

… Hermes flew

until the distant island lay ahead,

then rising shoreward from the violet ocean

he stepped up to the cave. Divine Kalypso,

the mistress of the isle, was now at home.

Upon her hearthstone a great fire blazing

scented the farthest shores with cedar smoke

and smoke of thyme, and singing high and low

in her sweet voice, before her loom a-weaving,

she passed her golden shuttle to and fro.A deep wood grew outside, with summer leaves

of alder and black poplar, pungent cypress.

Ornate birds here rested their stretched wings –

horned owls, falcons, cormorants – long-tongued

beachcombing birds, and followers of the sea.

Around the smoothwalled cave a crooking vine

held purple clusters under ply of green;

and four springs, bubbling up near one another

shallow and clear, took channels here and there

through beds of violets and tender parsley.

Even a god who found this place

would gaze, and feel his heart beat with delight;

so Hermes did; but when he had gazed his fill

he entered the wide cave.

Odysseus leaves Kalypso

Hermes tells Kalypso that she must release Odysseus and let him go home to his family. She has to obey, but when Hermes has left she cannot resist torturing Odysseus with the usual female question in this situation: how can you possibly prefer wifey to me, a goddess? To answer this Odysseus – πολύμητις ('polumetis'), the 'strategist', 'of many counsels', one of the standard epithets used of him – says all the right things. But she is just toying with him: she has no option but to follow Zeus' order to provide Odysseus with the tools and materials to build himself a raft and give him the provisions to sail towards the Phaiákian island of Skhería ('Phaecia'). There he will be welcomed, given treasure and provided with a boat and crew that will take him home.

Odysseus builds a shallow boat or raft with a single sail and rudder. The moment comes when he sets off.

This was the fourth day, when he had all ready;

on the fifth day, she sent him out to sea.

But first she bathed him, gave him a scented cloak,

and put on board a skin of dusky wine

with water in a bigger skin, and stores –

boiled meats and other victuals – in a bag.

Then she conjured a warm landbreeze to blowing –

joy for Odysseus when he shook out sail!

Now the great seaman, leaning on his oar,

steered all the night unsleeping, and his eyes

picked out the Pleiades, the laggard Ploughman,

and the Great Bear, that some have called the Wain,

pivoting in the sky before Orion;

of all the night's pure figures, she alone

would never bathe or dip in the Ocean stream.

These stars the beautiful Kalypso bade him

hold on his left hand as he crossed the main.

Seventeen nights and days in the open water

he sailed, before a dark shoreline appeared;

Skhería then came slowly into view

like a rough shield of bull's hide on the sea.

Poseidon intervenes

Poseidon, the god who for various reasons hates Odysseus, was not present at the council of the gods at which Zeus decided to free him from Kalypso and send him home. He spots Odysseus on his raft close to his destination, Skhería. Poseidon cannot simply drown Odysseus since this would violate the destiny assigned by Zeus, but he can make his passage as unpleasant as possible.

When reading this magnificent piece of narration, remember that this is the second oldest work of European literature.

But now the god of earthquake, storming home

over the mountains of Asia from the Sunburned land,

sighted him far away. The god grew sullen

and tossed his great head, muttering to himself:'Here is a pretty cruise! While I was gone

the gods have changed their minds about Odysseus.

Look at him now, just offshore of that island

that frees him from the bondage of his exile!

Still I can give him a rough ride in, and will'Brewing high thunderheads, he churned the deep

with both hands on his trident – called up wind

from every quarter, and sent a wall of rain

to blot out land and sea in torrential night.

Hurricane winds now struck from the South and East

shifting North West in a great spume of seas,

on which Odysseus' knees grew slack, his heart

sickened, and he said within himself:'Rag of man that I am, is this the end of me?

I fear the goddess told it all too well-

predicting great adversity at sea

and far from home. Now all things bear her out:

the whole rondure of heaven hooded so

by Zeus in woeful cloud, and the sea raging

under such winds. I am going down, that's sure.

How lucky those Danaans were who perished

on Troy's wide seaboard, serving the Atreidai!

Would God I, too, had died there – met my end

that time the Trojans made so many casts at me

when I stood by Akhilleus after death.

I should have had a soldier's burial

and praise from the Akhaians – not this choking

waiting for me at sea, unmarked and lonely.'A great wave drove at him with toppling crest

spinning him round, in one tremendous blow,

and he went plunging overboard, the oar-haft

wrenched from his grip. A gust that came on howling

at the same instant broke his mast in two,

hurling his yard and sail far out to leeward.

Now the big wave a long time kept him under,

helpless to surface, held by tons of water,

tangled, too, by the seacloak of Kalypso.

Long, long, until he came up spouting brine,

with streamlets gushing from his head and beard;

but still bethought him, half-drowned as he was,

to flounder for the boat and get a handhold

into the bilge – to crouch there, foiling death.

Across the foaming water, to and fro,

the boat careered like a ball of tumbleweed

blown on the autumn plains, but intact still.

So the winds drove this wreck over the deep,

East Wind and North Wind, then South Wind and West,

coursing each in turn to the brutal harry.

Leucothea to the rescue

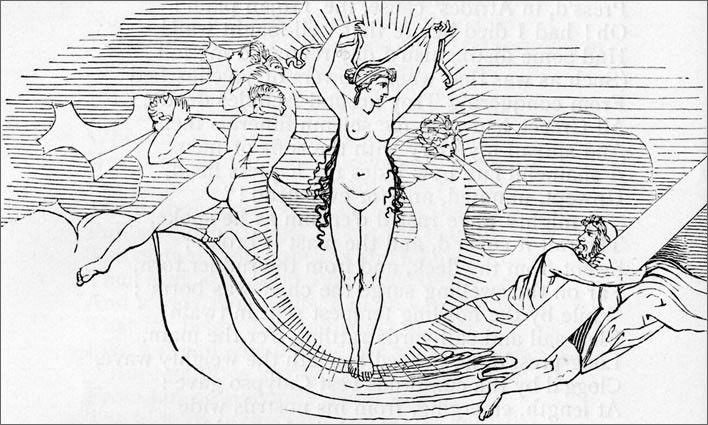

John Flaxman (1755-1826) was a busy artist, producing illustrations for heavyweights such as the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Divine Comedy and so on, all that in addition to his extensive sculptural work. His designs for Homer were published in 1793. He understandably did not have much time for detail and an underling did the actual engraving, but all the relevant elements are there: the winds, the veil and Odysseus clinging to the spar. Full marks for economy.

In this moment of extreme danger Odysseus is helped by the sea-nymph Leucothea, who manifests herself in the form of a seagull.

But Ino saw him – Ino, Kadmos' daughter,

slim-legged, lovely, once an earthling girl,

now in the seas a nereid, Leukothea.

Touched by Odysseus' painful buffeting

she broke the surface, like a diving bird,

to rest upon the tossing raft and say:'O forlorn man, I wonder

why the Earthshaker, Lord Poseidon, holds

this fearful grudge – father of all your woes.

He will not drown you, though, despite his rage.

You seem clear-headed still; do what I tell you.

Shed that cloak, let the gale take your craft,

and swim for it – swim hard to get ashore

upon Skhería, yonder,

where it is fated that you find a shelter.

Here: make my veil your sash; it is not mortal;

you cannot, now, be drowned or suffer harm.

Only, the instant you lay hold of earth,

discard it, cast it far, far out from shore

in the winedark sea again, and turn away.'After she had bestowed her veil, the nereid

dove like a gull to windward

where a dark waveside closed over her whiteness.

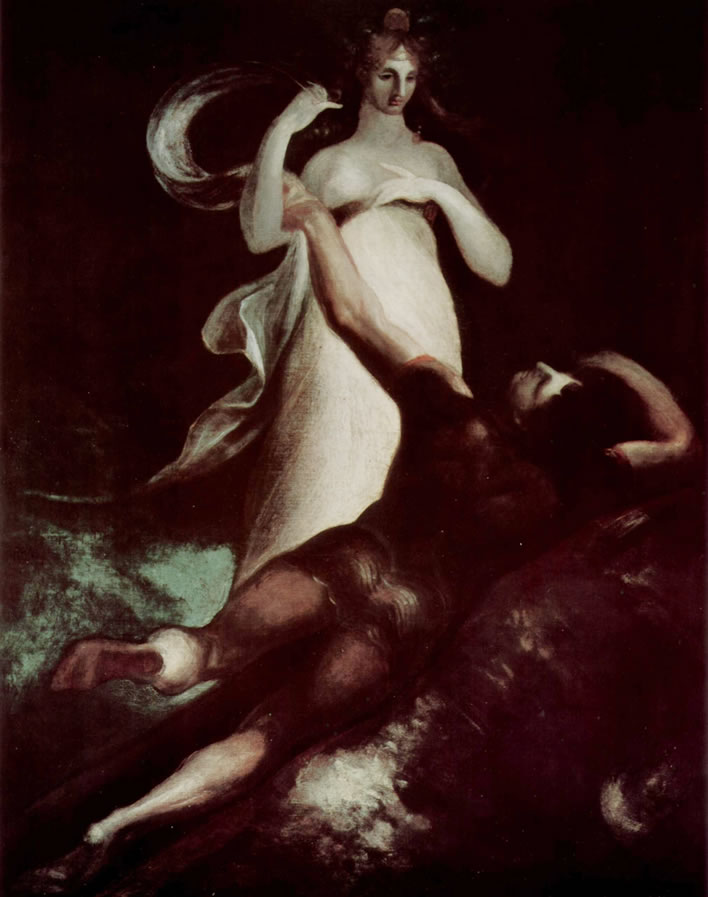

Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), a.k.a. Henry Fuseli, Der Schiffbruch des Odysseus, 'The Shipwreck of Odysseus' (1803? 1805-1810?). The painting is privately owned by the collector Ulla Dreyfus-Best in Basel. It saw the light of day briefly in the exhibition For Your Eyes Only. A Private Collection, from Mannerism to Surrealismat the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, May 24 – August 31, 2014. For €14 you could have caught a glimpse of it there.

I have not found any really acceptable photographs – my dislike of Füssli's caricature style means that I haven't tried very hard. There might be a better image in the catalogue of the exhibition, but that would have cost you €39.80. Nevertheless, we have Leukothea, Odysseus and a lively grasping for the veil that is not quite Homeric.

A veil for a cloak

We have already noted that both in the Iliad and the Odyssey Odysseus is the strategist – πολύμητις ('polumetis') – the cunning and cautious one. He never makes rash decisions. He keeps his counsel, awaits events and does not run unnecessarily into dangerous situations. This is so even in the present moment of extremis on the high seas, in which he does not immediately follow Leukothea's advice.

The heroes of the Christian tradition never dare doubt the instructions of God or one of his messengers; the more unquestioning they are, the better, as, for example in the case of Abraham and his son Isaac. Thomas the Doubter got a ticking off for needing evidence that Jesus had risen from the dead.

In contrast, the gods of the classical world are not renowned for honesty or fair dealing – so the wise human does not always take them at their word. When Kalypso told Odysseus that he was free to go he immediately suspected some trick, a cautious suspicion that the goddess not only did not hold against him but for which she praised him. We are in the classical world of divine trickery, not the Judeo-Christian world of a vengeful god requiring unqualified, unthinking obedience. Now Leucothea's help requires a leap of faith by Odysseus, a literal leap into a heaving, storm-tossed sea. He awaits events – but events make his mind up for him.

But in perplexity Odysseus

said to himself, his great heart laboring:'O damned confusion! Can this be a ruse

to trick me from the boat for some god's pleasure?

No I'll not swim; with my own eyes I saw

how far the land lies that she called my shelter.

Better to do the wise thing, as I see it.

While this poor planking holds, I stay aboard;

I may ride out the pounding of the storm,

or if she cracks up, take to the water then;

I cannot think it through a better way.'But even while he pondered and decided,

the god of earthquake heaved a wave against him

high as a rooftree and of awful gloom.

A gust of wind, hitting a pile of chaff,

will scatter all the parched stuff far and wide;

just so, when this gigantic billow struck

the boat's big timbers flew apart. Odysseus

clung to a single beam, like a jockey riding,

meanwhile stripping Kalypso's cloak away;

then he slung round his chest the veil of Ino

and plunged headfirst into the sea. His hands

went out to stroke, and he gave a swimmer's kick.

Note how the scented-cloak given to Odysseus by Kalypso, which we were explicitly told has become a hindrance, is discarded for Leukothea's veil. Those of a Neoplatonic cast of mind might care to interpret Kalypso's cloak as an image of physicality and lust, whereas Leucothea's veil is a spiritual aid – in which case replacing one with the other at this perilous moment becomes a highly significant act.

Landfall on Skhería

Athena, Odysseus' principal patron, helps to get him from the wreck to the shoreline.

But Zeus's daughter Athena countered him:

she checked the course of all the winds but one,

commanding them, 'Be quiet and go to sleep.'

Then sent a long swell running under a norther

to bear the prince Odysseus, back from danger,

to join the Phaiákians, people of the sea.

The veil is returned

The landfall is difficult, dangerous and painful but Odysseus is finally washed up on a beach. A wise and cautious man, he takes care to carry out Leukothea's instructions to return the veil to the sea when he has reached the shore. The bardic teller of the tale of the Odyssey would owe this act of fulfilment to his bronze-age audience.

In time, as air came back into his lungs

and warmth around his heart, he loosed the veil,

letting it drift away on the estuary

downstream to where a white wave took it under

and Ino's hands received it. Then the man

crawled to the river bank among the reeds

where, face down, he could kiss the soil of earth,

in his exhaustion murmuring to himself:

'What more can this hulk suffer? What comes now?…'

In the examination that now follows of Pound's use of the shipwreck theme in The Cantos the reader cannot be blamed for holding on tight to the mast during the buffeting that is to come. A veil may be thrown and we hope after the battering the reader may finally be able to 'kiss the soil of earth'.

References

-

^

There are other interpretations:

There was an old man called Ulysses,

Who wandered o'er hills and abysses.

He met with Calypso,

Who wiggled her hips so,

He was glad to get back to the missus.

H/t Uncle Frank RIP.

Update 25.05.2023

Reader Beth came up with the exact location of Johann Heinrich Füssli's work Der Schiffbruch des Odysseus. The caption has been revised accordingly.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!