The shipwreck in Thrones

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-08-15 07:46

Thrones de los cantares (XCVI-CIX) was published in 1959. Most if not all of the work had been written during the final years of Pound's incarceration in St. Elizabeths mental hospital in Washington. He was released from the institution in April 1958 as permanently and incurably insane and sent back to Italy.

Many Pound commentators cling to the comforting belief that his incarceration for insanity was just a judicial manoeuver to spare him prison or worse, a manoeuver with the unintended consequence that were he ever to be declared sane, the selection of treason charges he had faced were still pending. Had he just gone to trial and been sentenced it is arguable that he would have spent fewer years in prison than the 13 years he spent in the albeit more amenable mental hospital.

This narrative conveniently bypasses the main point: Pound was insane – he didn't need to feign insanity. Had he gone to trial, it would have become blindingly clear to the participants in the case after the first five minutes of his testimony that he was non compos mentis.

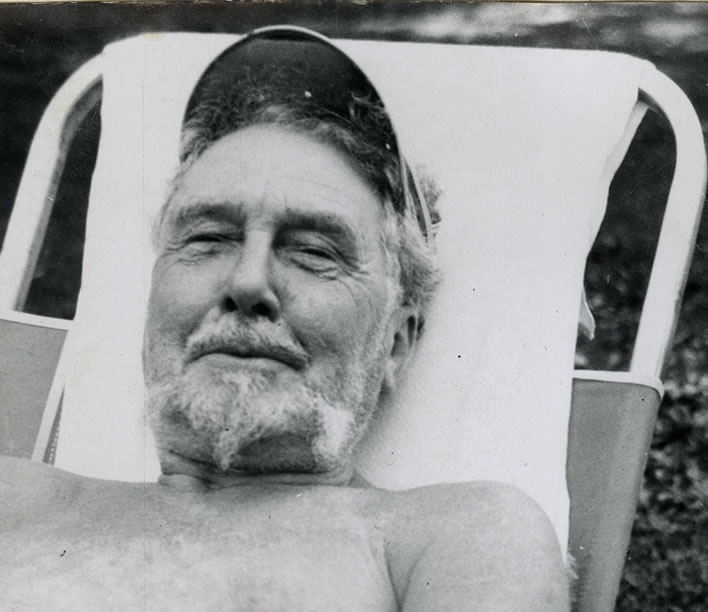

Ezra Pound in St. Elizabeths in March 1955. One of the very few photographs in which he is smiling. It's a hard life being crazy. Image: Beinecke Library, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

In the tempest

The reader, weary of the impenetrable, crazy-paving that is Rock-Drill, now moves on to the lunatic's latest epic, Thrones, with a heavy heart. At least we don't have far to go before we meet the first instance of the shipwreck theme: the very first line of the very first canto, Canto 96.

Κρήδεμνον…

κρήδεμνον…

and the wave concealed her,

dark mass of great water.

[C96:651]

Having established the striking and entertaining translation of Leukothea's 'bikini' in Rock-Drill, Pound now reverts to the Greek of the Odyssey: κρήδεμνον, 'veil' ('wimple', as I have seen it inventively translated). He follows it with two lines that are familiar to us shipwreckers and require no more comment.

Then, after an incomprehensible line about something or other, we are given two familiar lines:

& on the hearth burned cedar and juniper…

that should bear him through these diafana

[C96:651]

Shipwreckers will recognise the first of these two as a line from the description of the arrival of Hermes in Kalypso's sea-cave. The mention of 'diafana' will recall the discussion of the subject in our study of Rock-Drill C95:644. and the background discussion of the general topic. The syntax of this line is not immediately clear: we can only assume that it is the veil, κρήδεμνον, 'that should bear him through these diafana'.

Divine confusion

After this storming start we skip across three pages of incomprehensible ravings until we stumble across:

After 500 years, still sacrificed to that sea-gull,

a colony of Phaeacians θῖνα θαλασσης

[C96:654]

Ah, everything has been going so well up until now! Too well, in fact. We have arrived at the point where Pound starts to mix up two goddesses, Leukothea and Leukothoe. The two are quite distinct.

Leukothea, as we have seen, was formerly the mortal Ino, the daughter of the Theban king Kadmos.

Leukothoe, on the other hand, was daughter of Orchamus, king of Babylon. In her story Helios/Apollo, the sun god, loved/desired/ravished the unwilling Leukothoe. When Orchamus found out about this liason he buried his daughter alive. Through the intervention of Helios she was transformed into the frankincense bush.

More confusion, still to come: we also need to note that in the story of Leukothea, Athamas, who fell in love with Ino, was king of Orchomenus, thus providing even more scope for confusion.

Some maintain that Leukothoe is in some writers only another form for Leukothea. This assertion is simply not acceptable: the two deities have different narratives, different deaths and different manifestations. Apart from the similar name, there is nothing in common between them at all.

Pound muddles up both stories. Leukothea is the goddess of the shipwreck theme; Leukothoe appears three times in The Cantos, two of these times in close proximity to Leukothea. We shall come to these occasions soon, but we have to note here for the moment that 'still sacrificed to that sea-gull' actually refers to Leukothoe not Leukothea. Pound has mixed them up so that he is now mistakenly calling Leukothoe a sea-gull – which she never was. Clear? No, I thought so.

One final bit of Poundian affectation has to be disposed of: θῖνα θαλασσης, 'thina thalasses', 'shore [of the] sea' hints at that famous model of all Homeric epithets, which one first meets in the first lines of the Iliad: βῆ δ᾽ ἀκέων παρὰ θῖνα πολυφλοίσβοιο θαλάσσης, 'He went in silence along the shore of the loud-resounding sea' [IL:1:34]. The phrase occurs 16 times in the Odyssey, although not in the context of the shipwreck. It appears that Pound is aligning the Homeric epithet for the sea-shore with the Phaeacian colonies dotted around the shores of the Mediterranean – another gratuitous and ultimately pointless allusion to puzzle the reader and bring no one any further.

More divine confusion

We can now surge past 30 pages of the incomprehensible rubble from Pound's fractured mind until we come to the line:

Leukothea gave her veil to Odysseus

[C98:684]

A typical Pound problem of interpretation: we all know by now rather a lot about this line, but the purpose of its presence in the middle of a jumble of Greek, Chinese and other words from the Poundian rag-bag is beyond elucidation. A few lines further on θῖνα θαλασσης, 'thina thalasses' pops up again next to the phrase 'Thinning their oar-blades'. Is this one of Pound's exotic 'translations' that take his free-wheeling, associative mind from 'thinning' to 'thina'? And to what purpose? I have no idea. Locating the source in the Odyssey for the oar-blades allusion is beyond our scope. Row onwards!

On the next page we find ourselves in the middle of Pound's sea-gull confusion. Firstly, Leukothoe is introduced in the correct mythical context with the correct father and at the expected location:

And that Leukothoe rose as an incense bush

— Orchamus, Babylon —

resisting Apollo.

[C98:685]

However, we now step into the Leukothea myth, characterised by the sea-gull, Ino's father Kadmos, the Greek for her veil Χρήδεμνον and particularly the mention of sea-foam, which Pound has already established as a common property of Leukothea and Aphrodite:

Est deus in nobis.and

They still offer sacrifice to that sea-gull

est deus in nobis

Χρήδεμνον

She being of Cadmus line,

the snow’s lace is spread there like sea-foam

[C98:685]

Swinburne swimming

Brains still throbbing with effort, we can now put another 31 pages behind us to arrive at our shipwreck theme again:

So that the mist was quite white on that part of the sea-coast

Le Portel, Phaecia

[C100:716]

Following the allusion to white mist, source unknown (to me, anyway), Pound aligns the figure of Odysseus in trouble off the Phaecian coast and the Victorian poet Algernon Swinburne, a strong and frequent swimmer, who got into trouble off the French coast near the harbour of Le Portel and was rescued by some local fishermen. Pound first tells the story in an essay from 1918:

Thus departed his [Swinburne's] mundane glory, the glory of a red mane, the glory of the strong swimmer, of the swimmer who when he was pulled out of the channel apparently drowned, came to and held his French fishermen rescuers spellbound all the way to shore declaiming page after page of Hugo.

[LE:291 'Swinburne…']

More than a quarter of a century later Pound recalls this story from his London years in the Pisan Cantos:

When the french fishermen hauled him out he

recited 'em

might have been Aeschylus

till they got into Le Portel, or wherever

in the original

[C82:523]

Trivia addicts will observe that his memory is playing tricks with him – it was in a different anecdote from the 1918 essay that Swinburne recited Aeschylus.

Returning the veil

With the next lines we shipwreckers return to familiar territory, though this is the first time that Pound has dealt with Odysseus' successful landing and the return of the veil, bikini now scarf to Leukothea:

and he dropped the scarf in the tide-rips

KREDEMNON

that it should float back to the sea,

and that quickly

DEXATO XERSI

with a fond hand

AGERTHE

[C100:716]

The only new allusions are the two lines of Greek, both of which come from the scene of Odysseus' landing. DEXATO XERSI means to 'take into the hand' (αἶψα δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ Ἰνὼ / δέξατο χερσὶ φίλῃσιν – 'swiftly Ino took [the veil] into her hands', [OD:5:461-2]. 'Swiftly' (αἶψα) here gives us the source for the preceding line, 'and that quickly'.

The other allusion, AGERTHE (ἀγέρθη, 'gather together') takes us back to the moment a few lines earlier when Odysseus was washed up on the shore. Finally landed on the beach, he collapsed from his last gigantic efforts to get ashore, then he gradually came round (ἀλλ᾽ ὅτε δή ῥ᾽ ἄμπνυτο καὶ ἐς φρένα θυμὸς ἀγέρθη, 'and his spirit returned again into his breast', Od. 5:458). In the Fitzgerald translation we have used so far:

In time, as air came back into his lungs

and warmth around his heart, he loosed the veil,

Finally, 'with a fond hand' is a puzzle I cannot fully resolve – it may be a misreading, a mistranslation, one of Pound's 'creative' translations, it may be adapted from an idiosyncratic translation by W. H. D. Rouse 'until Ino quickly received it into her kind hands' (Rouse corresponded with Pound about his translation), or it may be from somewhere else. There comes a point when you run out of guessing energy.

Twelve more pages to be skipped until on page 728, right at the beginning of Canto 102 we find:

This I had from Kalupso

who had it from Hermes

[C102:728]

We shipwreckers have no difficulty attaching these lines to the visit Hermes pays to Kalypso to tell her of Zeus' order to release Odysseus, but how exactly we attach them may not be immediately clear, for this is not Odyssey Book 5, but Book 12, part of the tale of his adventures that Odysseus relates to his Phaecian hosts [OD:12:389f].

We skip a few lines of something or other and meet Leucothoe (as opposed to Leukothea):

keinas … e Orgei. line 639. Leucothoe

rose as an incense bush,

resisting Apollo,

Orchamus, Babylon

And after 500 years

still offered that shrub to the sea-gull,

Phaecians,

she being of Cadmus line

The snow’s lace washed here as sea-foam

[C102:728]

Just in case you are wondering, we note briefly that 'keinas … e Orgei. line 639.' is a quotation from the Odyssey [OD:4:693 (not 639)], κεῖνος δ᾽ οὔ ποτε πάμπαν ἀτάσθαλον ἄνδρα ἐώργει, 'No man alive could say Odysseus wronged him', the judgement of Odysseus' character by his wife Penelope, answering the question posed a few lines before this 'as to why Penelope waited'. Which, for us at the moment, is beside the point.

Having already discussed Leucothoe's story this passage presents no real terrors for us. The lines 'And after 500 years / still offered that shrub to the sea-gull,' are self explanatory, but their source is unknown.It is here that the confusion starts when the shrub identified with Leucothoe is offered to the sea-gull, who was Leukothea. Leukothea is Phaecian and a daughter of Kadmos; Leucothoe isn't.

Hair starts to be torn out, however, when Pound, as though we don't have enough confusion already, reminds us of the association he sees between Leukothea and the 'foam-born' Aphrodite.

A page later we have more about Leucothoe, superficially comprehensible, but the source and broader context is unknown.

But with Leucothoe's mind in that incense

All Babylon could not hold it down.

[C102:729f]

We paddle on above the chaos for another 25 pages until we reach page 755, where we notice that Pound has added one more 'white goddess' to the waterborne pantheon:

Selena, foam on the wave-swirl

[C106:755]

From here we can jump nearly 20 pages to the end of Thrones, where the shipwreck that was introduced at the beginning of the section with Leukothea's veil, κρήδεμνον, 'kredemnon' – I was about to write 'is brought to a close', but 'fizzles out' is a more apt expression. We battered shipwreckers will be able to understand most of this without difficulty now.

Over wicket gate

INO Ινώ Kadmeia

Erigena, Anselm,

the fight thru Herbert and Rémusat

Helios,

Καλλῐαστρἅγαλος Ino Kadmeia,

San Domenico, Santa Sabina,

Sta Maria Trastavere

in Cosmedin

Le chapeau melon de St Pierre

You in the dinghy (piccioletta) astern there!

[C109:774]

Let's choose to ignore all the things we don't understand: they are just part of the Poundian jumble we have had to skip over in order to arrive here at all. The only phrase worth further elucidation is Καλλῐαστρἅγαλος, which is the epithet applied to Leukothea in the Odyssey: 'beautiful ankled' – except that it isn't, because the word used in the Odyssey is καλλίσφυρος. The Greek word used by Pound, although it also means 'beautiful ankled', is only used in Aristotle's treatise on zoology, the Historia Animalium, according to Liddell and Scott, that source of all truth. Is this some subtle allusion? Did he just go to L&S and not the Odyssey for his Greek word? Was the eyesight of the poet in his seventies failing him? Why do we need to know this?

And, at last, at long last, Thrones is ended. '"O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" He chortled in his joy'. Pound's final line, You in the dinghy (piccioletta) astern there!, throws us back to near the end of Rock-Drill, to a section that we already discussed as being a distillation of the technique behind The Cantos:

'Oh you, as Dante says

'in the dinghy astern there'

There must be incognita

and in sea-caves

un lume pien’ di spiriti

and of memories,

Shall two know the same in their knowing?

[C93:631]

Leftover fragments of a cracked mind

We should stop here, but unfortunately for us, just when we think we have finished, perhaps even achieved an elegant completion of our journey through the shipwreck, we are confronted with the 'draft' of Canto 110, included in the Drafts and Fragments section at the end of The Cantos. Among the characteristic jumble and scatter of the late work we stumble across:

Foam and silk are thy fingers,

Kuanon,

[C110:778]

and a couple of pages later a repeat of the mangled 'beautiful-ankled' epithet which Pound applied to Leucothea:

KALLIASTRAGALOS

Καλλῐαστρἅγαλος

[C110:780]

And finally, the merest hint as the theme fades out completely:

lux enim—

versus this tempest.

[C110:781]

lux enim? The phrase is from Robert Grosseteste's work De Luce. The attentive reader, if still awake, will barely need to be reminded that the phrase stood at the beginning of Pound's 'Grosseteste telegram'.

Pound expects us to go from the fragment lux enim 'light, in fact' to Grosseteste's Lux enim per se in omnem partem se ipsam diffundit, ita ut a puncto lucis sphaera lucis quamvis magna subito generetur, nisi obsistat umbrosum, 'For light of its very nature diffuses itself in every direction in such a way that a point of light will produce instantaneously a sphere of light of any size whatsoever, unless some opaque object stands in the way.'

I could speculate, but I really have no idea what Pound is trying to tell us here. Whatever it is, it is 'versus this tempest', which we can probably assume to be the storm of the shipwreck… at least I think so.

Here his cracked mind supplies us with a perfect example of the incomprehensible juxtapositions that have made traversing his 'long poem' so annoyingly tedious for the reader. A good point to end.

No shore in sight

We note with little enthusiasm that Pound called Sheri Martinelli, a young painter hanging around the poet during his time in the mental hospital, his 'Leucothea'. A woman called Marcella Spann was also helping him in unspecified ways during his late years. Perhaps she was his Leukothoe. Traces of her are contained in Canto 113, we are told. Some vulgarians even believe that the one or the other or even – God help us! – both are something to do with the 'fond hand' allusion in C100:716. There's just something about ageing poets in lunatic asylums. It certainly doesn't work for ageing blog authors who perhaps ought to be in lunatic asylums.

His last dozen years were a great falling apart as depression and probably dementia worked their ministry that brought him to silence. Despite the women throwing their veils at him he never reached the shore of Phaecia and we are left only with the flotsam and jetsam of his shattered raft.

Ezra Pound photographed by Manfredi Bellati, undated.Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

Ezra Pound, undated. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 241, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

Ezra Pound, undated. Still grumpy after all these years. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 241, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!