The shipwreck in Rock Drill

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-08-15 07:45

Foolishly encouraged by our albeit tedious deconstruction of a few lines of the Pisan Cantos (cantos 74-84) perhaps you have plugged through the remainder of that group doing your own manifestation spotting. The thought of Pound, the broken poet in the prison camp, adds pathos and a personal dimension to these cantos to which many readers can relate; under the circumstances they may even make allowances for the disjointed rambling. If you have read all the Pisan Cantos you have ploughed through through ten cantos and 115 pages of poetry.

Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington D.C., 1954. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

The next decade of cantos, Section: Rock-Drill (cantos 85-95), 104 pages, is now ahead of us. Ezra, still safely under lock and key in St Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington, USA, published this group in 1956. Will the mad poet lure his readers gently into the new, paradisical section?

No. In modern parlance, the reader gets totally bitch-slapped from the first 'word' (an oversized Chinese ideogram, source naturally not mentioned) on the first page. Even the most well-disposed critic might call the remaining 'poetry' in Rock-Drill 'difficult'. It is, in fact, utterly obscure, the ravings of a lunatic who requires that his readers carry out hours of research in rare sources and from the results of those studies infer somehow the operation of his mind. Pound is unforgiving – his readers should be, too.

The mystic mind

Nevertheless, we shipwreck-theme hunters are robust souls. After the reefs and maelstroms of the Pisan Cantos we set sail in Rock-Drill, hoping for the best. Fortunately we are not committed to understand the material through which we are sailing. We surge past odd bits of flotsam – whence it comes, wherefore it is there and where it is going we have no idea. Do not stop! Do not fall in! After about 75 pages of being buffeted by 'challenging' 'poetry' we arrive at Canto 91. Only six more pages to go before we are suddenly shaken out of our heavy-lidded repose by the sound of our shipwreck-theme alarm going off – although, just a hint at first:

They who are skilled in fire

shall read

tan, the dawn.

Waiving no jot of the arcanum

(having his own mind to stand by him)

[C91:615]

When we read 'having his own mind to stand by him' we shipwreckers will immediately think back to the Odyssean shipwreck, when Leucothea observed 'You seem clear-headed still; do what I tell you.' We will also remember how Odysseus, the strategist – πολύμητις ('polumetis') – takes careful stock of the situation before he does what she tells him to do. This line comes in a context that is at the core of the shipwreck theme: the conjunction of divine aid and the robust mind.

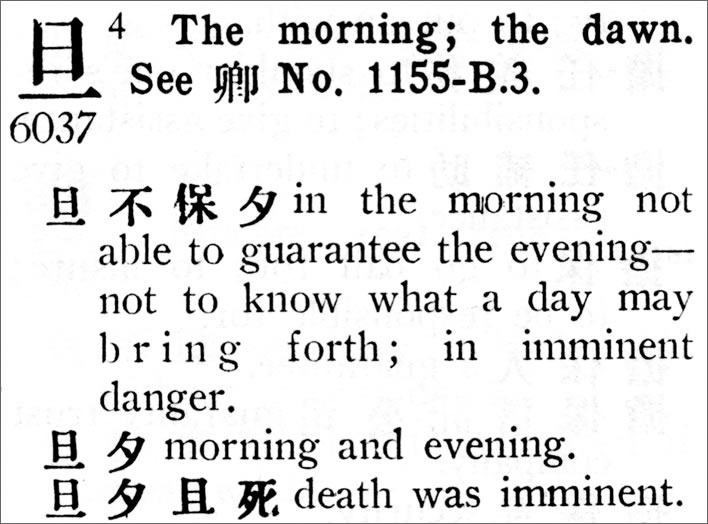

But, returning to the first of these lines, what about 'skilled in fire', the ideogram and 'the arcanum'? Let's start with the ideogram, tan(4).

The ideogram tan(4) is ideogram 6037 in Mathews'Chinese-English Dictionary, 1931, the dictionary used by Pound. Although Chinese ideograms have many phonetic components, Pound was always pleased when he could see a pictographic meaning in an ideogram. (Pound's pictographic insights into etymology can sometimes surprise native speakers.) The pictographic meaning of tan(4) is the 'sun over the horizon', which gives the semantic meaning of 'dawn' (don't ask why it doesn't mean 'sunset'; don't ask about 'evening' – picture of a cocktail shaker?). For Pound, ideograms became a kind of magical symbol, a signature, in which those skilled in such things can find representations of meaning.

In using tan(4) was Pound also alluding to the sample phrases given in Mathews: 'in the morning not able to guarantee the evening – not to know what a day may bring forth; in imminent danger'? This would seem to correspond very well with Odysseus' present predicament at the hands of Poseidon. It also corresponds well with the situation we shall meet when we discuss TLEMOUSUNE in a short while. Who knows?

'They who are skilled in fire' and 'Waiving no jot of the arcanum' are detours we must not take if we want to return before nightfall. We have to take a somewhat unsatisfying shortcut by filing these statements in the already overflowing folder marked 'Neoplatonic mysticism TBD'. Nevertheless, some background may help.

Pound wrote on many occasions of the Neoplatonic/Neopythagorean tradition, most accessibly in Guide to Kulchur, of 'man drunk with god, man inebriated with infinity'.

There is no doubt whatsoever that human beings are subject to emotion and that they attain to very fine, enjoyable and dynamic emotional states, which cause them to emit what to careful chartered accountants may seem intemperate language, as Iamblichus on the fire of the gods, 'tou ton theon pyros', etc. which comes down into a man and produces superior ecstasies, feelings of regained youth, super-youth and so forth, not to be surpassed by the first glass of absinthe (never to be regained by the second or 50th imbibition).

…

Two mystic states can be dissociated: the ecstatic-beneficent- and-benevolent, contemplation of the divine love, the divine splendour with goodwill toward others.

And the bestial, namely the fanatical, the man on fire with God and anxious to stick his snotty nose into other men's business or reprove his neighbour for having a set of tropisms different from that of the fanatic's, or for having the courage to live more greatly and openly.

The second set of mystic states is manifest in scarcity economists, in repressors etc.

The first state is a dynamism. It has, time and again, driven men to great living, it has given them courage to go on for decades in the face of public stupidity. It is paradisical and a reward in itself seeking naught further … perhaps because a feeling of certitude inheres in the state of feeling itself. The glory of life exists without further proof for this mystic.

…

What remains, and remains undeniable to and by the most hardened objectivist, is that a great number of men have had certain kinds of emotion and, magari, of ecstasy. They have left indelible records of ideas born of, or conjoined with, this ecstasy.

[GK:223f, chap. 39, 'NEO-PLATONICKS ETC']

Guide to Kulchur was written around 1938 and presents us with an entertaining and frustrating cross-section through Pound's fevered mind. The passages above, for example, can be taken as a pretty accurate executive summary of a large part of The Cantos. The duality at the heart of that work is clearly visible: the rants against the fanatics and the evil-doers, whether economical or political, and the praise of those driven by Neoplatonic perception of the divine to 'great living'. There are plenty of examples of the former up to and including the Pisan Cantos, 74-84. From Rock-Drill onwards we encounter the benign mystics and we are shown directly the 'contemplation of the divine love, the divine splendour'. But we also encountered light, fire and visions about thirty years before:

Iamblichus' light,

the souls ascending,

Sparks like a partridge covey,

Like the "ciocco", brand struck in the game

"Et omniformis" Air, fire, the pale soft light

Topaz I manage, and three sorts of blue,

but on the barb of time

The fire? always, and the vision always,

Ear dull, perhaps, with the vision, flitting

And fading at will…

[C5:17]

Iamblichus, light and fire are all here in Canto 5, written at the beginning of the 1920s. The vision of the spirits of the just rising up like sparks comes from Dante's Paradiso 18 ll. 100f.

Then, as when someone strikes a burning log ['ciocchi arsi'],

causing innumerable sparks to fly,

sparks from which the foolish form their divinations,

just so a thousand lights and more appeared

to rise from there and mount, some more, some less,

as the Sun that kindles them ordained.

Moving from the 1920s to 1956, we find Iamblichus' fire is still with us in Canto 91 of Rock-Drill and the visions are still flitting and fading in the mental hospital.

Life, a journey

Pound/Odysseus is on a journey through life. The Neoplatonic metaphor is of someone sailing over the nous, the fluid – the basis of all matter.

Gemistus Plethon brought over a species of Platonism to Italy in the 1430s

…

He was not a proper polytheist, in this sense: His gods come from Neptune, so that there is a single source of being, aquatic (udor, Thales etc. as you like, or what is the difference). [GK:224]

This journey is from the misapprehensions of the material world – we think of Plato's famous metaphor of the cave, that gloomy place in which unenlightened (pun intended) humans are chained in the dark and see only the shadows of things, themselves included, on the walls. The process of enlightenment consists in breaking the chains and journeying beyond the mouth of the cave into the light of the higher reality. Whatever the metaphor they used, Neoplatonists saw a process of enlightenment as a journey from the encumbrances and incorrect perceptions of the material world of shadows to the spiritual, unencumbered perception of reality, God, the Divine Mind, call it what you will.

Shines

in the mind of heaven God

who made it

more than the sun

in our eye.[C51:250]

This journey can be aided by spirits or gods acting as intercessors to the Divine Mind, but above all it requires that the traveller have an open and receptive mind: this journey is not for the stupid or the limited.

Now Pound has laid out the Neoplatonic/Neopythagorean component as a canvas or a context, as it were, we meet the shipwreck theme explicitly.

Mind and endurance

Odysseus is an example of a mind capable of self reliance: we remember his epithet is 'polumetis' – the many counselled, the strategist – at many points in the Odyssey he 'makes his own luck' as it were, by the sheer quality of his mind. His crew rush into the witch Circe's trap and are turned to swine, whereas Odysseus pauses, ponders and his reward is the intervention of Athena and Hermes, who help him at the critical moment to resist entrapment.

Unlike the dullards that are ordinary mortals, Odysseus' mind is always open to new knowledge. When he and his crew sail past the Sirens he plugs the ears of his men with wax: they are just there to row, their minds are closed to this experience. In contrast, Odysseus alone exposes himself to the Siren's deadly singing, for no purpose other than to add to his mind (eine Horizonterweiterung, 'an extension of one's horizon' as it is known in German) that he should know the song the Sirens sing. He could have just stopped his own ears.

In the Odyssey, ἀντίθεος, 'godlike, equal to the gods' is a frequent epithet of his. Zeus himself remarks upon the quality of that mind, whether 'godlike' or 'kingly':

Could I forget that kingly man, Odysseus? There is no mortal half so wise; [OD:1:65f tr. Fitzgerald]

How should I, then, forget godlike Odysseus, who is beyond all mortals in wisdom, [OD:1:65f tr. Murray]

In the shipwreck, Odysseus' mind is (cautiously) open to the goddess Leukothea, who takes pity on him and helps him at a critical moment. He is helped by the divine because his mind is open to that help.

As the sea-gull Κάδμου θυγάτηρ said to Odysseus

KADMOU THUGATER

'get rid of paraphernalia'[1]

TLEMOUSUNE

[C91:615]

In the shipwreck scene in the Odyssey, at the point when Leukothea the sea nereid appears to Odysseus in the form of a sea-gull, we are told she was Ino, the daughter of Kadmos –Κάδμου θυγάτηρ 'KADMOU THUGATER', as Pound transliterates it.

Kadmos is the soothsayer par excellence of Greek mythology whose legendary relations with the gods show the possibilities of divine-human communication.

Leukothea tells Odysseus to 'shed that cloak, let the gale take your craft, and swim for it' – in Pound's wonderful interpretation: 'get rid of paraphernalia'. From a Neoplatonic point of view, getting rid of 'paraphernalia' represents freeing the mind or soul from the clutter of the physical world that impedes it. As Pound wrote, eight pages before this:

Out of heaviness where no mind moves at all

'birds for the mind' said Richardus,

'beasts as to body, for know-how'

[C90:607]

Odysseus is not only freeing himself from the physical world but also from the world of human suffering. We may recall that Poseidon is not allowed to kill Odysseus, thus violating the wishes of Zeus, but his intention is to make him suffer: Odysseus may not encounter death itself, but he will certainly experience the fear of it.

Pounds now sets a single word, TLEMOUSUNE, written in capitals, almost as ideographic or as symbolic as tan(4). During Rock-Drill one of his principal sources is The Life of Apollonius of Tyana by Philostratus (172?-250?). Apollonius of Tyana (15?-100?) is a wandering sage and Neopythagorean or Neoplatonic philosopher who in his journeying incorporates the idea of the Odyssean wanderer and the model of the virtuous person. In the early Christian church he was sometimes equated with Jesus himself.

We are here mostly concerned with Book 7, during which Apollonius has been thrown into prison by the Roman emperor Domitian (51-96), who had a reputation as a particularly cruel and bloodthirsty emperor, even among that crowded field. Whether Domitian was really as bad as his reputation is beside the point – his name became a byword in antiquity for cruelty. Apollonius speaks to his fellow prisoners and hears much wailing and fear in expectation of what might happen to them. He tells them to wait and see what will happen, and not always expect the worst.

For it seems to me that you are ready to put yourselves to death and anticipate the death sentence which you expect will be pronounced against you; and so you show actual courage where you should feel fear, and fear where you should be courageous. This should not be; but you should bear in mind the words of Archilochus of Paros who says that the patience under adversity which he called endurance was a veritable discovery of the gods; for it will bear you up in your misery, just as a skilful pilot carries the bow of his ship above the wash of the sea, whenever the billows are raised higher than his bark.

[PHIL 7:26:280, the source from Archilochus is here.]

Pound extracts the word 'TLEMOUSUNE' from Apollonius' remarks 'patience under adversity which he called endurance' (τοῖς λυπηροῖς καρτερίαν τλημοσύνην). Conybeare, the translation Pound was using, renders it as 'endurance', though in other contexts it can be just 'misery' or 'suffering'. In a striking sailing metaphor Apollonius tells the prisoners that this quality of mind will 'bear you up in your misery'.

The conjunction of three ideas in those three lines therefore seems to be, firstly, the assistance of the divine in the form of the sea-nymph Leukothea, the daughter of Kadmos, 'KADMOU THUGATER'; secondly, a rejection of worldly things, 'get rid of paraphernalia' and thirdly patience in adversity, endurance, represented by 'TLEMOUSUNE'. Pound's striking text layout at this point presents us with the constellation: divine intervention – rejection of the physical – endurance.

And that even in the time of Domitian

one young man declined to be buggar'd.

[C91:615]

We stay with Apollonius for the next two lines, which are also taken from Book 7 of the The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, this time Chapter 42 [PHIL 7:42:295f]. The tale in the original is rather lengthy so we shall make do with a summary.

In prison Apollonius meets a beautiful young man from Arcadia. It turns out that the Emperor Domitian [famed, as already noted, for his degeneracy and violent cruelty] lusted after the young man, who refused his advances, for which Domitian put him in prison. The young man is nobly sticking to his principles: 'I am master of my person and shall guard it inviolate' – 'having his own mind to stand by him', in other words. When eventually Domitian may choose to take his vengeance, the young man says 'I shall simply hold out my neck, which is all his sword requires'. The young man's steadfastness was admired, not just by Apollonius but even by Domitian, and he was freed. The story encapsulates the Poundian principles so far: sticking to your principles and hoping for the best by not anticipating disaster before it happens.

'Is this a bath-house?'

ἄλλοτε δ᾽ αὖτ᾽ Εὖρος Ζεφύρῳ εἴξασκε διώκειν

'Or a Court House'

Asked Apollonius

[C91:615]

In the next lines we are faced with yet another scene from Apollonius, also from Book 7, this time chapter 31.

What has all this got to do with shipwrecks? you ask. Patience, I say, TLEMOUSUNE, you must endure this suffering with good grace.

Apollonius is on his way to the courthouse to appear before the emperor Domitian. In front of the courthouse he notes the commotion of those entering and leaving, saying that the scene reminds him of a bath-house. [PHIL 7:31:285f]

In between the two lines of this puzzling observation, the meaning of which I freely acknowledge I cannot remotely grasp, Pound slips in a line from the Odyssean shipwreck: ἄλλοτε δ᾽ αὖτ᾽ Εὖρος Ζεφύρῳ εἴξασκε διώκειν literally, 'and now again the East Wind would yield it to the West Wind to drive', which we meet in Fitzgerald's translation as:

So the winds drove this wreck over the deep,

East Wind and North Wind, then South Wind and West,

coursing each in turn to the brutal harry.

Make of this what you will.

Top or bottom?

There follow 13 lines of Neoplatonic, Neopythagorean gibberish over which we happily glide like Pound's water-bug glides over the nous until we arrive at a line that pulls us up short:

'my bikini is worth your raft'

[C91:615f]

A brilliant rendering of

Shed that cloak, let the gale take your craft,

and swim for it – swim hard to get ashore

upon Skhería, yonder,

where it is fated that you find a shelter.

Here: make my veil your sash; it is not mortal;

you cannot, now, be drowned or suffer harm.

As a very welcome distraction we note here the recent 70-year anniversary [July 1946] of the bikini, the swimwear named after Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, an obscure – that is, unless you were one of the unfortunates who lived there – group of atolls, which in turn was made famous after the atomic test series that began in that month. Only the French would name some skimpy swimwear after such a place and such an event, but then, they hold their national day on the anniversary of a questionable massacre, so the bar for taste does not seem to be set very high in that country.

Our picture editor could not find an image of a bikini, so you'll just have to use your imagination.

The daughter of Kadmos

Forging onwards, we shipwreck-themers can relax for the next three full cantos – 30 pages in fact. If you pause at any point to try and decipher the jumble of Chinese ideograms, Neoplatonic allusions and miscellaneous allusions to something or other, this short stretch will take you a long time indeed. We do it the thinking person's way: we go straight to page 644 – only four pages away from the end of Rock-Drill, where we find:

Queen of Heaven bring her repose

Κάδμου θυγάτηρ

[C95:644]

Κάδμου θυγάτηρ, 'Kadmou thugater', the 'daughter of Kadmos' is for us a now familiar epithet for the sea-nymph Leukothea. We already know a little bit about her from the description of her given in the Odyssey: In life she was the daughter of the Theban sage Kadmos, at which time she was called Ino. The initially puzzling line 'Queen of Heaven bring her repose' may begin to make sense when we know a little more of Ino's story.

Those who mess around with Classical mythology have to be aware that there is almost never one single tale, particularly about a popular goddess such as Leucothea. In the hands of numerous writers, dramatists and poets, mythic narratives were reshaped to meet requirements; different regions recast myths in ways that suited them; names were changed so that often the same basic story exists, just with different lists of dramatis personae and, on the other hand, the same names often figure in different and mutually incompatible stories.

Our caution here is enhanced by the fact that the brief mention of Ino-Leucothea in the shipwreck scene of the Odyssey is the first mention of her in Classical literature: this Homeric mention of her predates all other accounts. Let us try to put together a 'core story' concerning Ino without getting bogged down in the nuances of competing accounts. In this account nearly every statement ought to be followed by some indication of uncertainty such as '(?)' but our grown up readers are capable of taking these indications as read. For those who care about such things, the 'core story' here is based upon that found in the Bibliotheca of Apollodorus (nowadays, Pseudo-Apollodorus).

Ino was a daughter of the Theban sage Kadmos, an extremely important figure in Classical mythology, about whom many tales cluster. He also pops up in the early cantos [C4:13, C27:432] as a symbol of something or other, but there is no descernible connection with our shipwreck theme. One more thing to ignore.

Ezra seems to have selected the Homeric epithet for her, 'daughter of Kadmos', for special treatment in Rock-Drill. We note only that this epithet is not mentioned at all in the Pisan Cantos, where the shipwreck theme first occurs. The question of whether Pound's innovation is just taking over a convenient epithet from the Odyssey or projecting some deeper meaning through the inclusion of the name of Kadmos cannot be answered here – or anywhere else, probably.

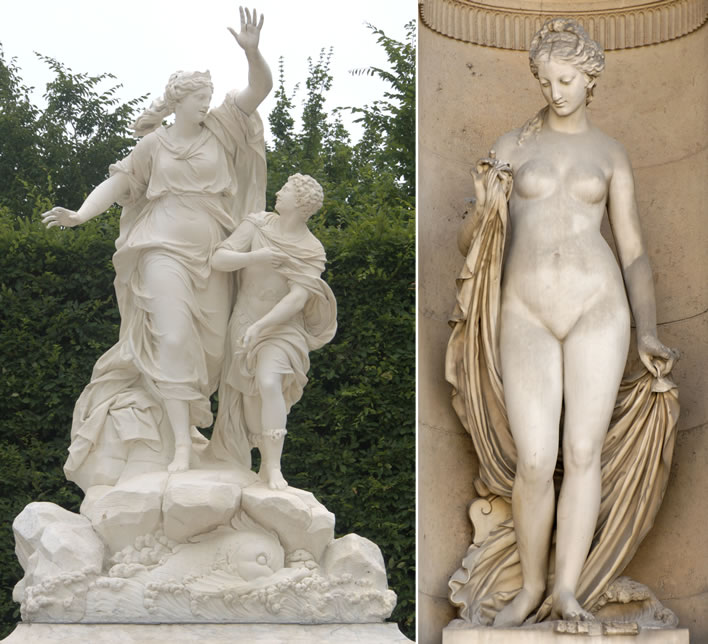

Left: Ino et Mélicerte (c. 1691) by Pierre Granier (1655-1715) in the Palace of Versailles. Melicertes is not being thrown by Ino, the two are going over the cliff together. The foaming sea and the fish are well-realised. Ino was transformed into the sea-nymph Leukothea, Melicertes into the sea-god Palaemon, who had his own cult following.

Right: Leucothea (1862), by Jean Jules Allasseur (1818-1903), one of the statues on the south façade of the Cour Carrée in the Palace of the Louvre, Paris. She is standing on some plank remnants, there is a breaking wave behind her and her veil is a substantial cloak.

Ino became the wife of Athamas, king of Orchomenus in Boeotia. Her sister Semele had the misfortune to be desired by Zeus – such things always end badly. Semele, six months pregnant with Zeus' child, entreated Zeus to appear to her just like he appeared to his wife, the goddess Hera, the 'queen of heaven'. The resultant divine entrance, 'thunderbolts and lightning, very, very frightening' (©Mercury, not Hermes), were just too much for Semele, who died of fright. Zeus took the six month old baby, carried it in his thigh for three months, then gave the baby to Hermes, who, in turn, gave him to Ino (Semele's sister) and her husband Athamas to raise as a girl. That baby was Dionysus, the 'wine god', the god of drunken madness.

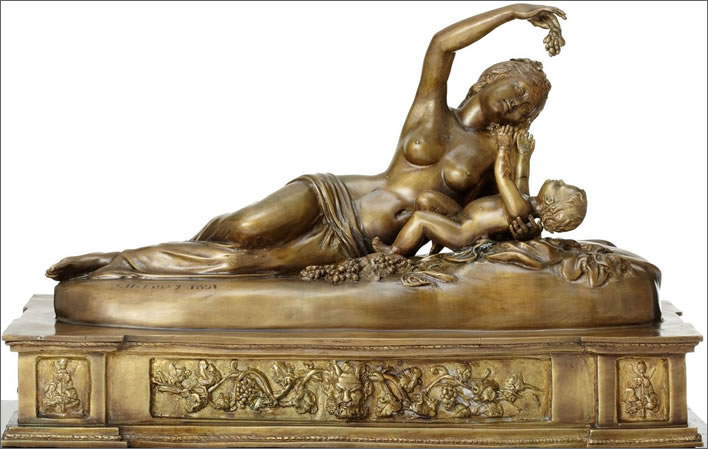

In Victorian Britain Ino was a relatively well-known mythological figure. Here are two related images of Ino bringing up Dionysius/Bacchus, the son of Zeus and Semele whom she fostered. The Irish sculptor John Henry Foley (1818-1874) first exhibited this subject, Ino and the infant Bacchus, as a plaster cast at the Royal Academy in 1840. This piece received widespread acclaim and helped start the young artist's career. A version in marble was commissioned by Francis, 1st Earl of Ellesmere for a substantial sum and completed in 1849. The engraving in the top image was made from the marble original for the Art Journal in 1849. Many copies and spin-offs of this charming and popular piece followed, particularly a very accurate Parianware copy by the Copeland factory. Both the original and the copies were exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The lower image is a bronze replica also dated 1851.

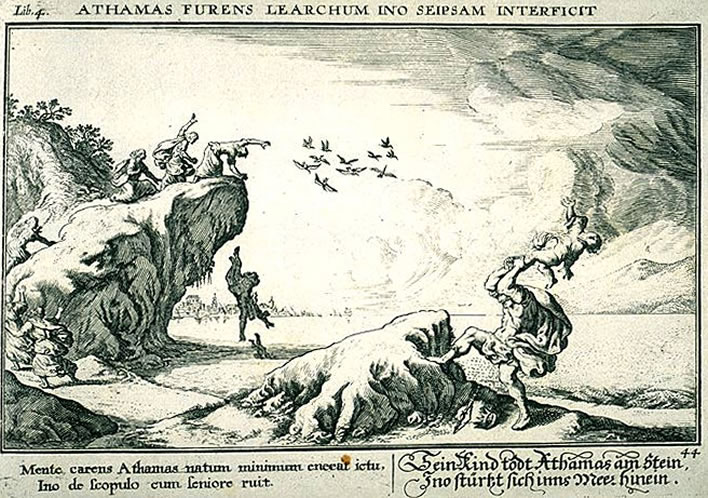

Hera found out about Zeus' philanderings with Semele and that the resultant child of that union, Dionysos, was being taken care of by Ino. Hell hath no fury, etc. Hera drove both Ino and husband Athamas mad. Athamas killed his eldest son. Ino killed her own son Melicertes and then jumped with him from a cliff into the sea. Zeus took pity on Ino and her son and transformed them into sea-gods: Ino became Leucothea and Melicertes the sea-god Palaemon.

The brutality of Hera's vengence on Ino and Athamas was also favourite theme for artists. This is an engraving by Johann Wilhelm Baur (1607-1640) made ca. 1640 showing the crazed Athamas beating his child to death on a rock while Ino and Melicertes cast themselves from a cliff into the sea.

A spectacular marble group by John Flaxman (1755-1826) The Fury of Athamas, 1793, now in Ickworth House, Suffolk.

Does 'Queen of Heaven' here refer to Hera? Does the line refer to Leucothea at all? If so, why should Hera, who caused Ino's madness and all the other disasters connected with it, why should she now 'bring her repose'? Perhaps the next line will help.

bringing light per diafana

[C95:644]

No, not really. It just takes us into that shadowy Poundian world of mystical light and shade we discussed in a previous section. Perhaps it describes the manifestation of one of Pound's female archetypes, in this case Leukothea:

λευκός Λευκόθεα

white foam, a sea-gull

[C95:644]

The manifestation – the transition from the divine world to the real world – occurs in parallel stages: the transformation of λευκός (white) into Λευκόθεα (white-goddess); the transformation of white foam into the seagull, who prefigures the goddess. We have already seen how, in Canto 74 of the Pisan Cantos, alongside the very first statement of the shipwreck theme, Pound has also immediately juxtaposed Aphrodite, the ‘foam-born’:

but this air brought her ashore a la marina

with the great shell borne on the seawaves

nautilis biancastra

[C74:443]

The identities of Pound’s divinities slip and slide. In Neoplatonic terms they are all merely facets of the 'One', the 'Mind of Heaven'. His female intercessors can manifest themselves as ‘Queen of Heaven’, such as the Virgin Mary or Hera, goddesses such as Aphrodite or Leukothea, beatified humans such as Perpetua, Agatha, Anastasia or, from a different canon, Tiro, Alcmene and Europa. The sea-foam from which Aphrodite was born is now also associated with Leukothea.

A few lines later we are told

That the crystal wave mount to flood surge

[C95:644]

the waves of the shipwreck being now the flood surge of the Neoplatonic nous.

After one more page of ideograms and ramblings we shipwreckers are brought up with a start. Pound's audacious reworking of Leukothea's veil into a bikini was clearly too good to let go, unfortunately spoiled by the misspelling of her name:

'My bikini is worth yr/ raft'. Said Leucothae

And if I see her not

No sight is worth the beauty of my thought.

[C95:645]

The two lines that follow it are Pound's translation of Bernart de Ventadorn's poem 'Can par la flors'. Attentive readers of The Cantos will recall that the Provencale original was quoted at the beginning of Canto 20, all that time ago:

Sound slender, quasi tinnula,

Ligur' aoide: Si no'us Vei, Domna don plus mi cal,

Negus vezer mon bel pensar no val"[C20:89]

Ezra – what else could we expect? – stirs in a few things for us to think about: 'quasi tinnula' comes from Catullus, Carmina 61, l. 13 'sing wedding songs with a voice like a bell [= a high voice]'; 'ligur' aoide' is derived from the description of the song of the Sirens in [OD:12:183], 'λιγυρὴν δ᾽ ἔντυνον ἀοιδήν', 'clear-toned song'; all sounds 'slender'. What exactly the relationship is between Leukothea and Bernart's lady is beyond me.

The next two lines are something to do with a sea-gull: their source and interpretation escapes me.

Lone rock for sea-gull

who can, in any case, rest on water!

[C95:646]

And finally, after all the hints and fragments und unconsummated manifestations, Rock-Drill ends with an almost complete account of the shipwreck, the elucidation of which will present you with (nearly) no more puzzles:

That the wave crashed, whirling the raft, then

Tearing the oar from his hand,

broke mast and yard-arm

And he was drawn down under wave,

The wind tossing,

Notus, Boreas,

as it were thistle-down.

Then Leucothea had pity,

'mortal once

Who now is a sea-god:

νόστου

γαίης Φαιήκων,…'

[C95:647]

The Greek of Leucothea's last words in Rock-Drill, νόστου γαίης Φαιήκων, 'go to the land of the Phaeacians' are from the shipwreck scene itself [OD:5:344f].

References

- ^ All the current texts of The Cantos have 'parapernalia', a clear misspelling, emended herewith to 'paraphernalia' [from παράφερνα, 'property outside a dowry'].

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!