Schubert in love

Richard Law, UTC 2019-12-21 08:16

The Esterházy dedication

In our last Schubert-themed piece we looked at the documentary traces of the concert given for Charlotte, Princess Kinsky, by Schubert and Baron Schönstein some time around the end of June and the beginning of July, 1828. A key element in understanding the few documentary fragments relating to this event was the dedication by Schubert of a group of four songs to Charlotte, Opus 96.

In the present piece we are going to use another of Schubert's dedications from 1828 to throw a little light on the tantalising relationship between Schubert and Countess Caroline Esterházy (1805-1851). This was his dedication to Caroline of the diaphanous four-handed Fantasy in F minor, Opus 103 (D 940).

A performance of the F minor Fantasy by Sivan Silver and Gil Garburg in 2011 (Jerusalem Music Centre). A video recording of a recent performance of theirs at the Konzerthaus Berlin is available on YouTube uploaded in January 2019 by the Bechstein company. The sound is pleasant, but your author prefers his Schubert without the emoting, gurning, rolling about and hand-waving on display there, but YouTube offers you a number of versions.

We discussed the relationship between Schubert and Caroline in our piece on Schubert's stay as a guest of the Esterházys at their country residence in Zseliz (now in the Czech Republic) in the summer of 1824.

The phrase 'discussed the relationship' is a rather affected way of saying 'listed the things we do not know'. The idea of a 'relationship' between the impecunious little nobody and an Esterházy countess is so absurd that it really should be dismissed out of hand. Readers who are not familiar with this theme might find it useful to read that piece before continuing here.

By 1828, Schubert and Caroline had known each other for around ten years. She and her older sister Marie had been receiving piano lessons from Schubert since some time before Schubert's first stay with the family in Zseliz in 1818. As far as we know, the lessons continued in the period between the first Zseliz stay and the second in 1824. It also seems that the lessons continued, for Caroline at least, into 1828. At this time Schubert was thirty-one and Caroline was twenty-two. This makes her, as far as we know, the longest-serving pupil Schubert ever taught.

Although some records suggest that the older sister, Marie, was the more accomplished pianist of the two, Caroline, from the evidence of her post-Schubert existence, seems to have been talented in her own right.

Josef Teltscher, Countess Caroline Esterházy de Galántha, 1828, the year of the dedication of the Fantasy. She is twenty-three years old. This portrait was used by Moritz von Schwind as the model for the painting of Caroline in his well-known depiction of a Schubert Evening (below). Image: An etching from a lost watercolour, source unknown.

It is fair to assume that by 1828, Schubert's commerce with the family was quite relaxed. On his first stay with the Esterházys in 1818 he was treated much as a domestic servant would have been. By the time of his second stay in 1824, his status was much more elevated. It would have been clear to the family by then that their summer music master was not the usual penniless pianist trying to make a crust. After four further years, though never a social equal, Schubert would have felt comfortable around the family and they around him.

Even so, the formalities involved in the dedication of a piece of music were in full force, even between people who were as socially close as Schubert and Caroline.

His dedication to Caroline of the four-handed Fantasy in F minor, Opus 103 (D 940) is the one piece of hard documentary evidence (as opposed to anecdotal material) of whatever relationship there may have been between them that we have.

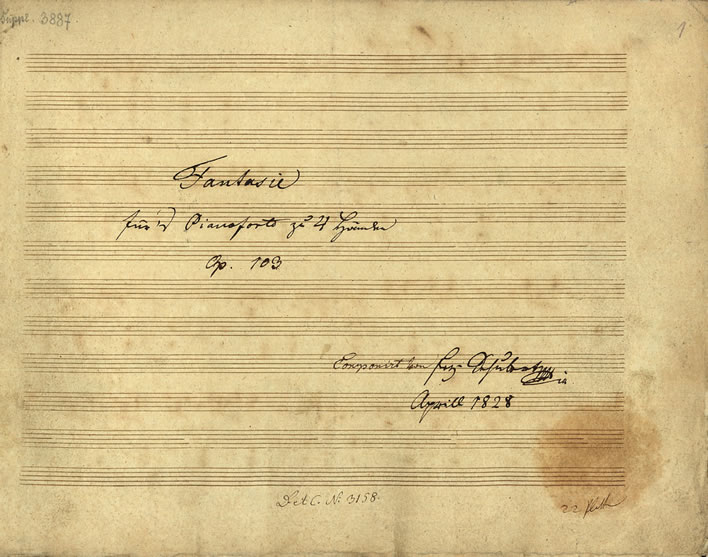

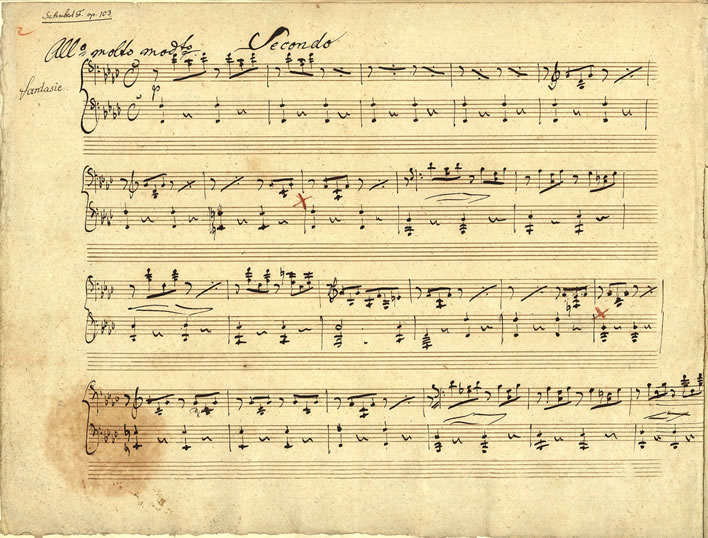

Although the piece was only published posthumously in March 1829, its creation took place in early 1828. Deutsch tells us [Dok 496] that it was sketched out in January and finished (and dedicated) in February. The fair copy was ready in April and Schubert and Lachner performed it on 9 May 1828 before Eduard Bauernfeld [Dok 515].

In our piece about the dedication of the four songs of Opus 96 to Charlotte Kinsky we specified the formal steps that were required when a composer wished to dedicate a piece to someone. Briefly: a written request from the composer to the dedicatee, a written acceptance from the dedicatee to the composer, the production of the work bearing the dedication and finally the presentation of the dedicatee with a copy of the work. Let us apply similar reasoning to the dedication of the four-handed Fantasy in F minor to Caroline Esterházy.

The attainment of one of the fixed points in this procedure was marked in Schubert's letter of 21 February 1828 to the German music publisher B Schotts Söhne. The publisher had written to him on 9 February asking him, in the most complimentary terms, whether he had any compositions available. They would, they wrote, always welcome 'Piano works or songs for one or more voices with or without piano accompaniment' [Dok 493].

Schubert, productive beyond the capacity of the Viennese music publishers, wrote back listing ten(!) works that were currently sitting in that musical logjam – plus, almost as an aside (to prove that he is a serious composer, he says), 'three operas, a Mass and a symphony'.

We might burst out laughing at the absurdity of it all, only to catch ourselves and remember the frustration which Schubert must have felt at this situation. The very existence of that logjam tells us a lot about Schubert's economic situation at the time.

Reading of this logjam, we think back to the printing by Schober of the four songs of Opus 96 dedicated to Charlotte Kinsky and now suspect another reason why the job was given to him: a traditional music publisher might have needed up to a year to produce this work. By using Schober's limping printing company the job was done and the dedication paid for in a matter of weeks.

Schober's company was already tottering when he bought it and the signs of its imminent demise were clear for everyone to see – it finally expired around the time that Schubert did, although its death throes took longer.

The piece dedicated to Caroline, in contrast, followed the conventional route to publication. Why? Ask no questions, get told no lies. But that route followed the leisurely course that had been such a frustration to Schubert during his life: although the fair copy for printing was finished in April 1828, it was almost exactly a year, on 16 March 1829, before it emerged from the logjam into the by then posthumous light. QED.

Returning to Schubert's February letter to the German music publisher, the fourth work in the logjam list was:

Fantasy for pianoforte for four hands, dedicated to the Countess Caroline Esterházy.

Fantaisie fürs Pianoforte zu 4 Hände, der Comtesse Caroline Esterhazy dediciert.

[Dok 495]

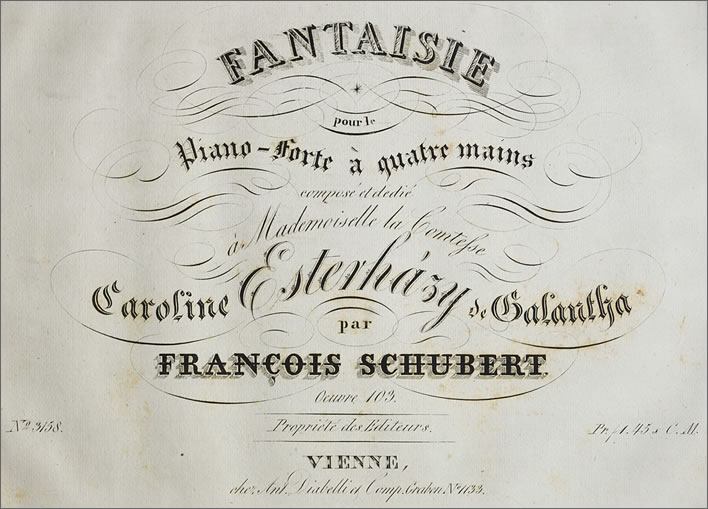

That Schubert explicitly adds a dedication to this entry – and only this entry – in an otherwise business-like list of compositions tells us how important having an aristocratic dedicatee was for the sales prospects of a piece. Any doubts we may still have are dispelled when we look at the dominance of that dedication on the cover page of the score when it was finally published by the Viennese publisher Diabelli a year later. Our eyes tell us that this is a dedication with a score attached.

The title page of the first edition of the Fantasy in F minor, published in 1829. Fantaisie pour le Piano-Forte à quatre mains composé et dedié à Mademoiselle la Comtesse Caroline Esterházy de Galantha par François Schubert. Ant. Diabelli und Comp. D.et.C.No.3158. Image: Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek.

The existence of this piece and its dedication to Caroline also tell us that the contact with her was (still) active in 1828 – the relationship between them did not fizzle out after Schubert's second stay with the Esterházys in Zseliz in 1824. The fact that there are no documentary traces of a relationship (of whatever form) between them in the three and a half years from then until now does not mean that the relationship did not continue.

The existence of this dedication, so firmly and ostentatiously asserted by Schubert on 28 February 1828, tells us that he must have requested the dedication some time before.

It seems reasonable therefore to follow Deutsch's statement that the Fantasy was completed in February; it also seems reasonable to imagine that Schubert's request for Caroline's dedication occurred at a mutual play through of the piece around late January or early February. Not only was Caroline a competent musician in her own right, quite capable of playing the Fantasy, probably even on sight, she was also indisputably the moving spirit behind Schubert's composition of so many of his four-handed pieces.

We might even allow our own fantasy to take flight, imagining that sister Marie supplied one pair of hands when Schubert's pair was not there, but Marie had married shortly before, on 13 November 1827 and was thus probably out of the house.

The fair copy was not finished until April 1828, which means that Caroline gave her permission for her dedication on the basis of a working version. The fair copy, which was intended to be used for the printed version has no dedication written on to it.

We have a vision of two temperamentally aligned pianists enjoying the creative moment, for Caroline the pleasure of playing and hearing a piece that no one else in the world had heard, a piece which would be dedicated to her.

The cover page and first page (secondo) of the Fantasy in F minor in Schubert's fair copy manuscript of April 1828. Fantasie in f für Klavier zu 4 Händen / Aprill 1828. Image: Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek.

The first other person to hear it performed seems to have been Schubert's great friend of the time Eduard Bauernfeld, a music connoisseur among his other accomplishments, who was given a performance by Schubert and Lachner on Friday 9 May. [Dok 515]

The passion burned inside him right until his end

We have looked at various aspects of Schubert's relationship with Caroline Esterházy, principally in our piece on Schubert's second stay with the Esterházy family in Zseliz in 1824.

If Schubert's first stay in 1818 can be described as taking place in the aura of the two girls Pepi Pöcklhofer and Therese Tschekal – Caroline was thirteen at the time – that second stay was bathed in the light from Caroline Esterházy (1805-1851), then nineteen years old and already an accomplished pianist.

Caroline Countess Esterházy, etching from a now lost watercolour by Anton Hähnisch, c. 1845. She was around forty years old at the time of this portrait. On 8 April in the previous year she had married in Bratislava Count Karl Folliott de Crenneville-Poutet. Image: ÖNB/284.386-B.

As we noted then, the idea of any kind of conventional romantic relationship between 'Caroline, the young Esterházy countess and the penniless, short, fat, unimposing, syphilitic, low-born underling Schubert would be a joke'. But this was not a conventional relationship. It was a community of spirit between two fellow musicians.

From the carefully curated collection of scores and manuscripts she left at her death, we know that she was no aristocratic music dilettante. If we let our fantasy run free and we magic away all the immense social impediments to such a union, we might just imagine the relationship between Schubert and Caroline might have been similar to that between Robert and Clara Schumann (syphilis included).

Witness: Schönstein

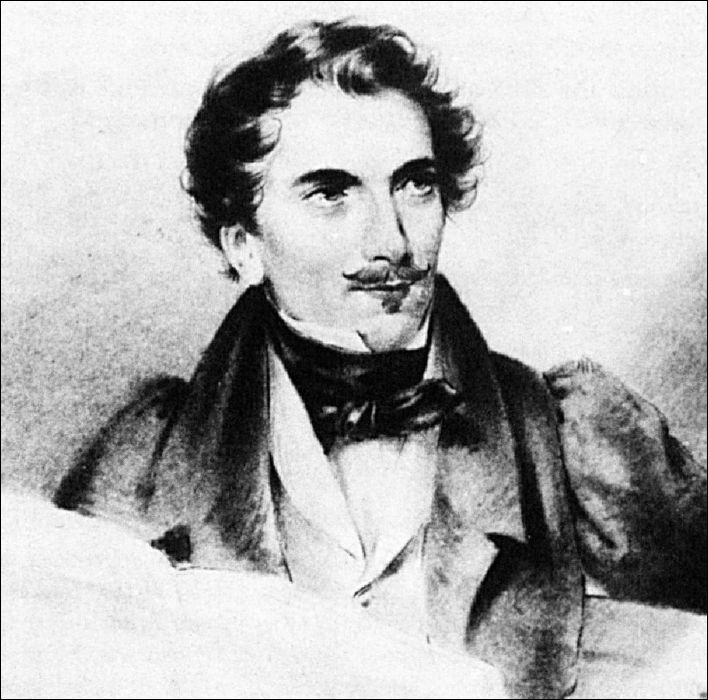

Karl Freiherr von Schönstein, watercolour by Josef Teltscher, c. end of the 1820s. Image: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, I.N. 133.942/42 in [Steblin 93 34]

We return here, too, to the recollections of Baron Schönstein. When it comes to details, his recollections are not to be trusted, but on general points he has insights that seem quite reasonable. He was, after all, an eyewitness, a friend of both the Esterházys and Schubert. Schönstein tells us that:

The family Esterházy rapidly recognised the musically creative riches that Schubert possessed; he became a favourite of the family, remained during the winter as their music master at home and accompanied the family in later summers on their country estate in Hungary. He was frequently in the Esterházy home right up to his death.

A love affair with a servant, which Schubert began soon after his entry among the Esterházys gave way in turn to the more poetic flame which rose inside him for the younger daughter of the family. This passion burned inside him right until his end.

Welch musikalisch-schöpferischer Reichtum in Schubert lag, erkannte man bald im Hause Esterházy; er wurde ein Liebling der Familie, blieb auch über Winter in Wien Musikmeister im Hause und begleitete die Familie auch spätere Sommer hindurch auf das genannte Landgut in Ungarn. Er war überhaupt bis zu seinem Tode viel im Hause des Grafen Esterházy.

Ein Liebesverhältnis mit einer Dienerin, welches Schubert in diesem Hause bald nach seinem Eintritt in dasselbe anknüpfte, wich in der Folge einer poetischeren Flamme, welche für die jüngere Tochter des Hauses, Komtesse Karoline, in seinem Inneren emporschlug. Dieselbe loderte fort bis an sein Ende. [Erinn 116]

Despite all our reservations about the quality of Schönstein's memories, his explicit remark that Schubert's passion for Caroline 'burned inside him right until his end' makes it clear that Schubert's passion did not end on leaving Zseliz in 1824.

To this statement we must add Schönstein's other remark, that Schubert 'was frequently in the Esterházy home right up to his death'. Whatever the relationship between Caroline and Schubert, it was certainly not a holiday romance which stayed in Zseliz. Schönstein's memories are sometimes a little jumbled, but there was no reason for him simply to make either of these statements up.

And now, in February 1828, when we find the documentary evidence of the dedication lying in plain sight that Schubert and Caroline's relationship must have continued from 1824, we re-read Schönstein's statement that Schubert 'was frequently in the Esterházy home right up to his death' and see that, whatever weight we might place on 'frequently', the statement was essentially correct.

In which case we have yet more evidence of Caroline's musical talent and sensitivity: with or without his feelings for her, would he have kept on giving lessons to a mediocre musician for so many years?

But Schönstein went further on the subject of the relationship between Schubert and Caroline:

Caroline esteemed his talent very highly, but did not return this love, perhaps she did not realise the degree to which it existed. I say 'the degree', because that he loved her must have been clear to her from a remark of Schubert's – his only expression [of his love] in words. When she once jokingly teased Schubert that he had never dedicated a piece of his to her he responded: 'Why do that? Everything is dedicated to you anyway.' The dedication of Opus 103 to her was done by Diabelli after Schubert's death.

Karoline schätzte ihn und sein Talent sehr hoch, erwiderte jedoch diese Liebe nicht, vielleicht ahnte sie dieselbe auch nicht einmal in dem Grade, als sie vorhanden war. Ich sage, {in dem Grade}, denn {daß} er sie liebe, mußte ihr durch eine Äußerung Schuberts – die einzige Erklärung in Worten – klargeworden sein. Als sie nämlich einst Schubert im Scherz vorgeworfen, er habe ihr noch gar kein Musikstück dediziert, erwiderte jener: »Wozu denn, es ist Ihnen ja ohnehin alles gewidmet.« Die Dedikation des Opus 103 erfolgte erst nach Schuberts Tod durch Diabelli.[Erinn 116]

Although Schönstein's account was written in 1857, almost thirty years after Schubert's death, his observations in this matter are credible on the whole: he knew everyone concerned intimately and was a close party to all these events. Nor, unlike some Schubert memorialists, does he have the slightest need to inflate the closeness of his relationship with Schubert.

He only errs in stating that the dedication of the Fantasia in F minor for four hands, D 940, was done by Diabelli – we know that it had been accepted by Caroline some time before mid February. He is correct, though, if we take his reference to Diabelli as relating to the first printed version of the score.

As far as the dedication itself is concerned, we have no paper trail between Schubert's letter in February 1828 and Diabelli's printed score in March 1829 – that is, we have no idea how the dedication was transmitted to Diabelli, or even whether the publisher himself had to confirm the dedication with Caroline, the composer being already in his grave.

Schönstein's recollections in many cases are so erratic that the temptation always to put on latex gloves when coming into contact with them is very great. But, 'nothing ventured, nothing gained' – occasionally we need to risk some measured speculation in order to get us a step or two further out of this cloud of unknowing. In this case, Schönstein's report of the exchange between Schubert and Caroline on the subject of dedications is there in front of us, waiting for us to do something with it.

Before we even get into the details of what Schönstein tells us in this last excerpt, we have to note the striking Gelassenheit, 'easy-going calmness' with which he views the prospect of a relationship between the young Esterházy countess and the musical nobody. Whilst we old maids are fluttering our fans in shock at the very thought of it, Schönstein takes it all in his relaxed stride. He seems to believe that, had Caroline been more compliant, something might have come of this extremely odd pairing.

Unlike Joseph von Spaun's fantasy of Schubert's conversation with Princess Charlotte Kinsky, Schönstein's anecdote strikes us as extremely plausible – it rings true. Schönstein is the observer, we hear the teasing, rather flighty Caroline and we hear Schubert's desperate terseness.

We have yet another witness to Schubert's almost pathological introversion, particular in respect of women. Schönstein's phrase 'perhaps she did not realise the degree to which it existed' strikes us a completely credible when we think back to the relationship Schubert was supposed to have had around 1816 with Therese Grob (1798-1875), his 'first love'.

Even today scholars argue about whether this relationship existed or not, but the most striking witness to it was Therese Grob herself, now the bourgeois widow Therese Bergmann, who, when asked fifty-odd years later about Schubert's passion for her, said that she had no idea that such a passion had existed – the shy and introverted composer had given her no sign of his feelings, if those they were.

Here we are again, twelve tumultuous years of Schubert's life later, in exactly the same situation with the Countess Caroline. Schubert simply did not have the interpersonal skills necessary to signal his passion to a woman.

This very introversion makes Schubert's outburst that 'everything is dedicated to you anyway' the more believable. If the flirting valve is absent, all that is left is the occasional, somewhat inappropriate outburst. Even the most introverted personality can break into speech, however laconic, however allusive, at the right trigger.

And most seductive of all for our present theme, the conversation revolves around a dedication. Was this the 1828 dedication? Might Caroline's teasing have been the trigger that led to the dedication of the F minor Fantasy, perhaps even to its composition as a platform for that purpose?

Schönstein did not mince his words about Schubert's feelings for Caroline, his expression 'the passion burned inside him right until his end' is startlingly intense.

Witness: Bauernfeld

Eduard von Bauernfeld, ND. A lithograph by Franz Stöber based on a sketch by Moritz Michael Daffinger. Although the date is unknown it is probably some time in the late 1820s (Franz Stöber died in 1834). Image: Source unknown.

Supporting evidence for the intensity of the relationship between Schubert and Caroline comes from an entry made by Eduard Bauernfeld in his diary in February 1828. The entry is valuable as evidence, since not only was Bauernfeld one of those closest to Schubert at that time, his entry was made contemporaneously and is not some vague memory thirty years after the fact. He tells us:

Schubert seems to be seriously in love with Countess E[sterházy]. I like that in him. He is giving her lessons.

Schubert scheint im Ernst in die Comtesse E. verliebt. Mir gefällt das von ihm. Er gibt ihr Lektion. [Steblin 93 24]

The language of Bauernfeld's note gives us another reason to take his remark seriously. He was a wordsmith by nature with a habit of careful expression. In his memories of Schubert he can at times be too much of a novelist in search of a literary effect. But here, even though he is writing for himself, his words are carefully chosen and deserve our respect: 'seems to be seriously in love'. Schubert's courage in confronting the social absurdity of such a relationship even gains the respect of the womaniser Bauernfeld, himself never one to shirk the challenge of a conquest: 'I like that in him'. This is not confected gossip.

Bauernfeld in his private, contemporaneous account, confirms the two main thrusts of Schönstein's memoir: Schubert was in love with Caroline and was giving her lessons – that is, he was in regular contact with his beloved. As in the case of Schönstein's assessment of the intensity of the love, Bauernfeld's phrase 'seriously in love' is startling, especially coming as it does from such a serial flirter and seducer.

However, we sit up and pay particular attention when we read that Bauernfeld wrote this diary entry in February 1828. Wasn't that the month in which Schubert finished the F minor Fantasy and dedicated it to Countess Caroline? And let us not forget, either, that it was Bauernfeld who was party to a private performance of the piece by Schubert and Lachner in May.

Witness: Schwind

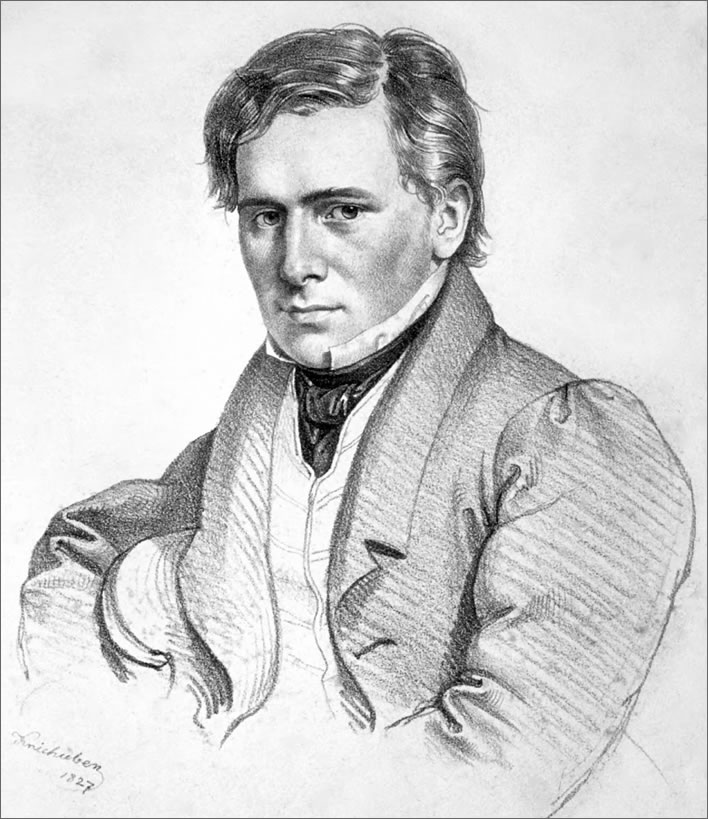

Josef Kriehuber, Portrait of Moritz von Schwind, lithograph, 1827.

The youngsters in close proximity to Schubert in 1828 were above all Eduard Bauernfeld and Moritz von Schwind, who had been schoolfriends. Bauernfeld we have to thank for his openness in his diary on the subject of Schubert's love for Caroline, Schwind we also have to thank for giving us another clue:

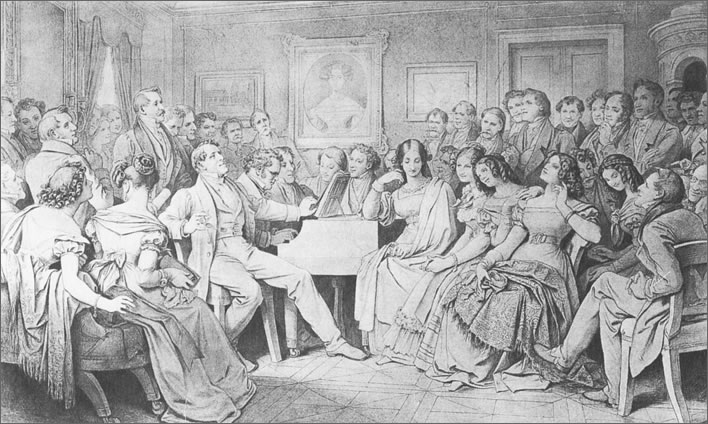

Moritz von Schwind's homage Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun, 'A Schubert evening at Josef von Spaun's'.

This illustration was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life. The full title of the work is Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun and it is held to represent the last Schubertiade, that was held at Joseph von Spaun's house on 28 January 1828.

The fact that Schwind rejects the Schober branding 'Schubertiade' and prefers the more generic 'A Schubert Evening' is probably another indicator of the dislike that Schwind felt for his one-time friend Schober by the time of this picture.

Just as in the case of Baron Schönstein, Schwind is constructing this illustration many years after the fact. But where Schönstein is frustratingly vague with his dates, Schwind is remarkably precise.

The last Schubertiade dates from early 1828, the same period in which we first encounter Schubert's dedication of the F minor Fantasy to Caroline and the same period in which Bauernfeld noted that Schubert was 'seriously in love' with the Countess. In this crucial period Schwind has mounted a great portrait of her on the wall. Her dominant and unmistakable image, which he appears to have derived from Teltscher's portrait (shown above), looks down over the entire gathering: a visual artist's way of saying: 'Everything is dedicated to you anyway'.

Of course, that portrait would not have been hanging in Spaun's drawing room. It is an artefact consciously placed by Schwind to tell us who the goddess was whose emotional aegis was spread over Schubert in 1828. His admirers are clustered around him, but the goddess Caroline, his unreachable donna, is there as a shadowy presence, looking down upon him.

Non-witness: Spaun

Joseph von Spaun, in his copious memoirs, mentions nothing of this. His delicacy, his civil servant's sense of decorum, stays his pen. He criticised Kreißle, Schubert's first biographer, for including personal details about Schubert and speculating (however daintily) on the composer's love life and drinking habits. We can expect no salacious gossip about Caroline from him.

We might also argue that Spaun, ten years older than Schubert and the elder statesmen of the first 'Circles of Friends', now, in April 1828, married to a wealthy, mature woman, was somewhat out of the Schubert loop by 1828.

In contrast, women were much on the young minds of Bauernfeld and Schwind at the time, seemingly Schubert, too.

1828 and all that

Always a good antidote for spinning heads, let's make a Schubert-Caroline timeline. From this we see that Caroline seems not to have been far from his thoughts in the first half of the year.

| Esterházy silence. | |

| 1818.07-11 | Zseliz stay with the Esterházys. Schubert (21). The children — Marie-Therese (16, 1802-1837), — Caroline (13, 1805-1851) and — Albert János (5, 1813-1845). |

| Six years of Esterházy silence. | |

| 1824.05-10 | Zseliz stay with the Esterházys. Schubert (27). The children — Marie-Therese (22), — Caroline (18) and — Albert János (11). |

| Three and a half years of Esterházy silence. | |

| 1828.01 | Fantasy in F minor drafted. |

| 1828.01.28 | Last Schubertiade, setting for Schwind's : 'Ein Schubert-Abend by Josef von Spaun' (1868). |

| 1828.02 | Bauernfeld: 'Schubert seems to be seriously in love with Countess E'. |

| 1828.02.21 | Fantasy in F minor announced as 'dedicated'. |

| 1828.03.26 | Schubert's concert. |

| 1828.04 | Fantasy in F minor fair copy. |

| 1828.05.09 | Fantasy in F minor performed by Schubert and Lachner for Bauernfeld. |

| 1828.06.03 | Schubert's fugue in Heiligenkreuz (with Lachner) |

| 1828.09.01 | Schubert moves out of Schober's and in with brother Ferdinand. |

| 1828.09.25 | Schubert finally calls off (after numerous postponements) his trip to the Pachlers in Graz. |

| 1828.09.27 | Musical evening with Dr Menz and Baron von Schönstein. |

| 1828.10.05 | Three day hike with Ferdinand et al. |

| 1828.11.10 | Schubert's illness strikes. |

| 1828.11.19 | Schubert dies. |

| 1829.03.16 | Fantasy in F minor for four hands published by Diabelli. |

In 1828 the Hartmann brothers kept up their diaries of life among the Schubert circle. They tell us of much sociability, drinking and talk – but almost nothing of what the talk was about. We would be surprised – shocked, even – were Caroline ever the subject of coffee house chatter.

In 1828 we have some earnest business correspondence to and from Schubert and there are some advertisements and reviews from newspapers. We have some entries from Bauernfeld's journal and a few letters from friends, mostly to other people.

Even the definitive cancellation of his trip to Graz at the end of September was written not to Frau Pachler, the most directly affected person, but in a brief, emotion-free note to Jenger. This is a surprise, because from their correspondence the year before we might have considered them almost soulmates.

But Schubert, in the weeks before his mortal illness, has entered the zone of apathy familiar to all depressives: in the few words we have of him he complains repeatedly of Mattigkeit, 'listlessness', 'exhaustion'; old habits die hard – he is manically focused on his music, his refuge in previous dark times but now that logjam that now cannot be freed, only added to; he deals with pressing business, mainly appeals for payment, but leaves personal relationships, which will only make the depression worse, to one side. He hardly ever wrote about such things at the best of times.

In 1828 we have next to nothing left about the composer, certainly not a word from Schubert himself concerning personal matters beyond his immediate hypochondria. Presumably Caroline is on the summer estate in Zseliz.

Conclusion

Our knowledge of the later Schubert is scrappy, even scrappier than the earlier Schubert – which is saying something. What we have is like a text scattered across the tattered shreds of an ancient papyrus. There are great gaps where we know nothing and never will, but there are places where the surrounding text, grammar, syntax and convention lead us to speculative readings of what might be in those gaps. Schubert's death year, 1828, so full of gaps, is full of such possibilities.

We have attempted one of those speculative readings today. In 1828 – and perhaps long before – Schubert had a life and seems to have had a love. We have not the slightest trace of evidence that his love for Caroline was requited, so in fact our discussion of a 'relationship' between them is otiose.

Nevertheless, it seems to have been, if not a reality, then at least a spook inside Schubert's mind, that spook that we see looking down on him in Schwind's drawing. If that spook gave us the F minor Fantasy, then so be it – at least something came of it. We could argue it also gave us the three great piano sonatas, D 958, D 959 and D 960, the Impromptus, D 899, D 935 and much, much more. After all, we recall, 'Everything is dedicated to you anyway.'

After Schubert's death, Caroline waited a long time before involving herself with another man. For whatever reason she chose one with a limited, mediocre mind, a relationship which turned out to be a disaster – though mercifully short-lived.

What we don't know – and probably never will – is her own feelings about the composer who loved her. Did she remain in ignorance of his passion? Did she suspect but not encourage, perhaps actively deter him? Did she care at all, or not at all? Was she concerned about the scandal of such an unequal association? The mystery of the four missed summers when Schubert did not go to Zseliz also hangs over us. Did she attend his concert in March 1828? Did she attend his funeral? What kind of life did she have, after her Schubert had died?

Whatever the answers to these questions, there is still only one question: how many of the great love stories of history can be crowned with a work as subtle and loving as the great F minor Fantasy? Shades talk, shadows, too and music also.

Sources

All translations ©FoS.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

| Steblin 93 | Steblin, Rita. 'Neue Forschungsaspekte zu Caroline Esterházy' in Schubert durch die Brille 11, June 1993, p. 21-34. [DE] |

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!