Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock: Der Zürchersee

Posted by Richard on UTC 2018-07-30 17:26 Updated on UTC 2020-10-22

'The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.' L.P. Hartley's (1895-1972) justly famous opening sentence of his 1953 book The Go-Between could admittedly do duty as the opening sentence of every encounter with the historical record ever written.

The distant country for today's visit is to be found in a poem written by the German writer Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803). Superficially, it is an account of a boat journey he took on the Lake of Zurich with young Swiss friends on 30 July 1750 and the bucolic hanky-panky that accompanied it.

Hartley's metaphor is completely apposite: things are done very differently in that distant country of the mid-18th century. There will be many things that puzzle us and strain our understanding, but, in the end, that's why we visit foreign countries, isn't it? – travel, as we all know, broadens the mind.

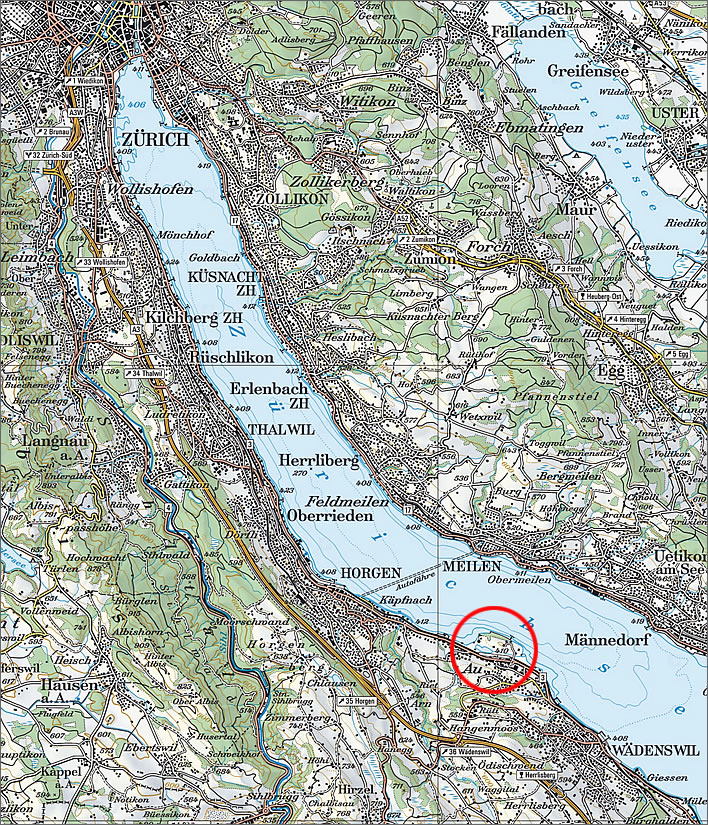

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803). Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Klopstock's poem is called Der Zürchersee, 'The Zurich Lake'. The title leads us to expect a traditional poetic postcard, a traveller's paean to some striking landscape. That is not what we get at all – not at all. We have entered a very distant country where things are done very differently indeed.

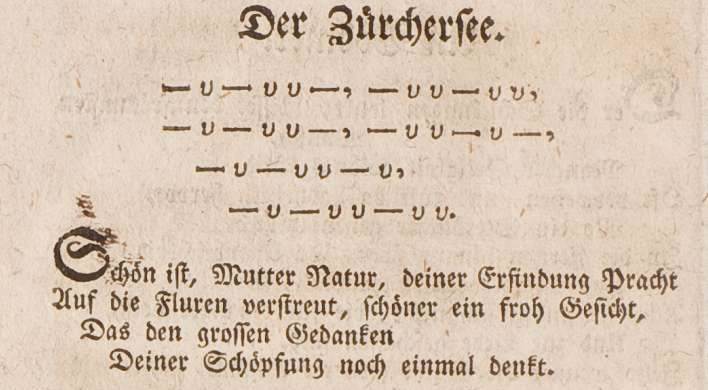

Right at the entrance to this strange world, before we have even stepped in the boat, we stumble over this:

— v — v v —, — v v — v v,

— v — v v —, — v v — v —,

— v — v v — v,

— v — v v — v v.

Our travel guide to this strange country tells us that this is the metrical scheme for the 'third Asclepiadean ode': four lines with 12, 12, 7 and 8 syllables respectively. The long vowels are marked with '—', the short vowels with 'v'.

Detail of Der Zürchersee, from Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Oden, Hamburg, 1771. Online.

Before we even consider the deeper meaning of the scheme we have to give vent to our surprise at the appearance of this diagram at the beginning of Klopstock's poem. When was the last time that you saw such a thing reproduced at the head of a poem? Certainly not in Maya Angelou's stuff.

Klopstock seems to be ostentatiously advertising the strictness of his adherence to some classical model. Why we need to be shown this is not clear to us travellers – are we going to be required to give the poem marks out of ten for metrical compliance? In many later printings of the ode the metrical scheme is left out, but these are not versions direct from Klopstock's hand. We must therefore assume that the display of the scheme is really his intention. How distant this all is!

Beware the Greeks bringing metrical gifts

There was a fad in English poetry at the end of the nineteenth century for writing within the confines of strict and archaic verse forms – the triolet, the sestina etc. – but even the most scholarly versifier never thought of printing a diagram of the metrical scheme at the beginning of a work.

After the antique verse boom of the 1890s and early 1900s all this technical stuff became embarrassing in the English-speaking world: we had free verse and free love and anybody could be a poet. What's a 'triolet', anyway? Some poets such as Dylan Thomas, trying to be 'poets', resuscitated some of the old forms but came to grief on their lack of mastery of the schemes or the incongruence of them to their subject.

In 1893, at the height of the verse boom, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch (1863-1944) wrote an amusing account of an estate gardener's passion for the lady of the manor in the form of a Sapphic ode, a close relative of the Asclepiadean ode that we have before us and a notorious challenge for the English language. Here's a taste:

But the nineteenth spring, i' the Castle post-bag,

Came by book-post Bill's catalogue o' seedlings

Mark'd wi' blue ink at 'Paragraphs relatin'

Mainly to Pumpkins.'

And its conclusion:

Simple this tale!—but delicately perfumed

As the sweet roadside honeysuckle. That's why,

Difficult though its metre was to tackle,

I'm glad I wrote it.

'Lady Jane / Sapphics', Quiller-Couch, Arthur Thomas, in Green Bays / Verses and Parodies by Q, London, 1893, Methuen, p. 13.

Writing antique verse forms in a modern language is a task only for obsessives or people trapped in a cave awaiting rescue. True, in such schemes the poet no longer needs to find rhymes, but has to handle a structure of short and long vowels in languages in which they are now overwhelmed with stress or beats.

Klopstock was the first German writer fully to master antique metric schemes and he did so by declaring German stressed syllables to be the equivalent of classical long syllables and unstressed syllables ditto classical short syllables.

Furthermore, in German, unlike English, the writer has a tremendous flexibility of sentence order, so he or she is relatively free to move words around at will to make them fit the scheme. Let's take an English sentence and rearrange it in the same ways that German sentences can be rearranged:

It's a long way to Tipperary.

A long way it is to Tipperary.

A long way to Tipperary it is.

To Tipperary a long way it is.

After the initial, 'standard' sentence order, native English speakers will find these sentences increasingly bizarre – unless, of course, they are fans of Yoda in the Star Wars movie franchise. In contrast, their German equivalents, literally translated, would all be perfectly acceptable to native German speakers. The flexibility of sentence order in German is one of the literary strengths of the language, used to great effect by good writers and speakers down the ages.

The sublime: rare and difficult

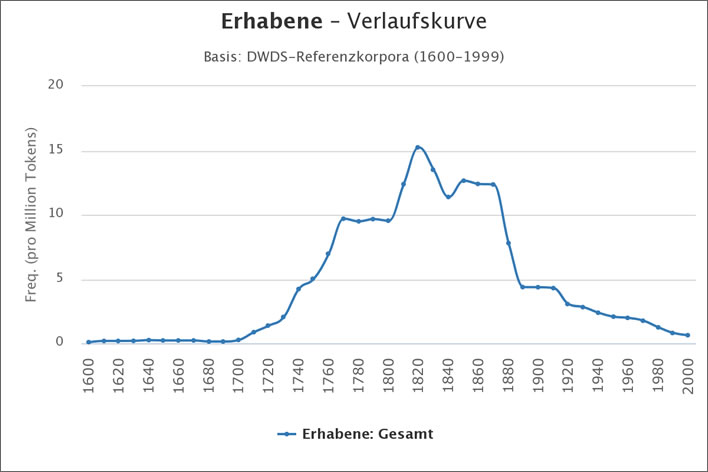

Klopstock not only perpetrated whatever acts of violence on the sentence structure of German he required in order to fit it into a classical verse scheme, he went one step further: he strained for the 'sublime' (die Erhabenheit).

Unfortunately, Klopstock equated the sublime with complexity and rareness – that the sublime might be simple never entered his head. Doctorates have yet to be written on the intersection of the complexity of the rococo mind of the age and the idea of the 'sublime' that passed down the ages from Aristotle, Horace and Longinus into the mind of their great admirer, Klopstock. Our battered reader groans: 'No, no – not that!' A good point well made. Let's move on and leave the doctorates unwritten.

Another famous statement is on hand to help us understand Klopstock's viewpoint: the renowned last sentence of the last proposition of the last book of Spinoza's Ethics (1677): 'But all things bright/excellent are as difficult as they are rare.' (Sed omnia praeclara tam difficilia, quam rara sunt). The sublime: difficult of understanding and far removed from the everyday.

In Klopstock's poem even the contemporary reader was going to have to work hard to grasp the excellence, the sublimity of his verse. The modern reader, unused to these constructions, is frequently frustrated. We moderns may chuckle at Klopstock's idea of the literary sublime, but we are in a different country, remember – best not mock.

The occurrence of the word 'Erhabene' in the DWDS reference text corpus between 1600 and 1990. The boom in the pursuit of the 'sublime' began around 1700, levelled for about fifty years after the approximate time of Klopstock's boat journey, took off again in 1800, peaked and then held its own until the 1880s, after which German writers seem to have had enough of the 'sublime'. Of course, the values from 1900 to 1990 possibly represent the use of the word by people writing about the eighteenth century. Image: Korpustreffer für "Erhabene", aus dem 'Korpus Deutsches Textarchiv des Digitalen Wörterbuchs der deutschen Sprache'.

As part of the complexity and difficult rarity of this sublimity, Klopstock leveraged in particular the power of the German genitive (a.k.a. the possessive) to new levels. An example of this in English would be: 'Odes Klopstock's poem's brief first pages' title is'. Native speakers of English will have no difficulty understanding this – at the third reading.

The reader interjects: why are you subjecting English speakers, of all people, to this German maniac?

Well, I did warn you that the past was a distant country where things are done differently. But take heart, you are not alone: today's native speakers of German will have to read a Klopstock verse several times over, not just to understand it (they haven't even got to that part yet) but simply to parse it. It is conceivable that native German speakers may understand the English translations and paraphrases here better than they do Klopstock's original text. The German-speaking 18th-century is a distant country for them, too.

An aside for the Schubert fans on this website: it doesn't surprise us that the Piarist and ex-Jesuit pedants who educated Franz Schubert in the Viennese Stadtkonvikt (1808-1812) were big Klopstock fans; nor does it surprise us that the poor lad, no matter how desperate he was for texts for his song compositions, generally kept away from the great man's work.

In Klopstock's The Zurich Lake all its ends are deep: we may as well just dive in at the beginning and see if we ever resurface.

Der Zürchersee

Schön ist, Mutter Natur, deiner Erfindung Pracht

Auf die Fluren verstreut, schöner ein froh Gesicht,

Das den grossen Gedanken

Deiner Schöpfung noch einmal denkt.

The Zurich Lake

How beautiful is the splendour of your inventions, scattered across the land, Mother Nature; more beautiful yet is the joyful face [of someone] as it reflects on the great thoughts of your creation.

We saw that at the head of the poem Klopstock laid out his metrical scheme. We can do him the courtesy of just checking – if only for this first strophe. A blue highlight marks the 'long' or 'stressed' vowels (—), a green one the 'short' or 'unstressed' vowels (v).

— v — v v —, —vv—vv,

Schön ist, Mutter Natur, deiner Erfindung Pracht

— v — v v —, —vv—v—,

Auf die Fluren verstreut, schöner ein froh Gesicht,

— v — v v — v,

Das den grossen Gedanken

— v — v v — v v.

Deiner Schöpfung noch einmal denkt.

Well done, that man! Only another 18 strophes to go.

We spoke above of Klopstock's metrical innovation in making a German stressed vowel the equivalent of a Greek or Latin long vowel. We now have an example of this before us, in that the 'i' in the German word Gesicht is stressed – we say Ges-i-cht, not G-e-sicht, but no one would attempt to say Ges-iiiii-cht. In addition, purists would find the subordinate metrical role of the most important word on the first line Pracht, 'splendour', rather odd. It has definitely a short vowel, but a sensitive, syntactically and lexically aware reader would want to give it the greater stress it deserves.

Strophe 1: The primacy of feelings

The first strophe contains the seed of the ideas behind much of the remainder of the poem. It is not simply some gentle introduction to the body of the work, but an encapsulation of its central theme.

Paraphrasing: the glories of Nature may be wonderful in themselves, but not as wonderful as the human experience of them, the effect they have on the human.

Right from the beginning, Klopstock is emphasising the importance of perception, sensitivity, sensibility, receptivity, responsiveness and all the other words you might use to translate the German word Empfindsamkeit. The primary factor in perception and thought is not the thing in itself, but the emotions that it arouses in the human observer. Klopstock is a poet, not a philosopher and therefore uses 'a joyful face' as a metonomy for 'a joyful person' and thus for the abstractions of pleasure or happiness.

The construction of the 'great thoughts' of nature 'den grossen Gedanken' upon which the human observer 'reflects' or 'thinks', 'denkt ', with such pleasure could have come straight from the Neoplatonist Plotinus: the Divine Mind and the bliss for the human mind in its the contemplation of it. We should not be afraid of such interpretations, for there is scarcely any other way to read it – and besides, we need only to recall that Klopstock's aesthetic guide, Longinus, was also a disciple of Plotinus.

Now we have disentangled the difficulties of the first strophe, we confront an astonishing beauty that makes us recall Spinoza 'But all things bright/excellent are as difficult as they are rare'– we have overcome the difficilia and attained those things that are praeclara, bright or excellent, to discover a sentence so lambent that it will shine in a German speaker's mind ever after. It is a strophe so speakable, singable even, that once you have it it will never leave you. Klopstock, the forgotten poet, defies all my mockery.

It is telling, though, that modern German articles on Klopstock almost always quote this strophe. It is even more telling that they almost never quote any of the other eighteen.

Strophe 2, 3: The arrival of pleasure

After disentangling the convolutions of the first strophe and marvelling at the beauty exposed therein there is no time to relax: Klopstock spreads his next sentence backwards over two strophes, which we therefore have to take together. Another few steps up Mount Klopstock, the north face direttissima:

Von des schimmernden Sees Traubengestaden her,

Oder, flohest du schon wieder zum Himmel auf,

Komm in röthendem Strale

Auf dem Flügel der Abendluft,

From the vinyards on the banks of the shimmering lake, or, should you once more have fled to the heavens, come in a reddening beam on the wings of the evening air,

Komm, und lehre mein Lied jugendlich heiter seyn,

Süsse Freude, wie du! gleich dem beseelteren

Schnellen Jauchzen des Jünglings,

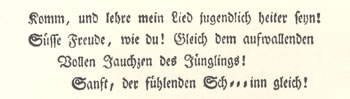

Sanft, der fühlenden Fanny gleich.

come and teach my song to be youthfully happy, sweet Pleasure, like you! Like the soulfuller frequent shouts of joy of the young men, or gently, like the empathetic Fanny.

The first sentence actually starts in the middle of the second strophe. Let's paraphrase both of the strophes using conventional word order:

Sweet Pleasure, come from the vinyards on the banks of the shimmering lake, or, [at evening] come in a reddening beam on the wings of the evening air, come and teach my song to be youthfully happy, like you are! Like the animated and frequent cries of the young men or like the empathetic Fanny.

The word beseelteren is an example of the Klopstock comparative, one of his trademarks. Klopstock is using beseelt here in the sense of 'lively' or 'animated' – the latter being an almost literal translation.

These two strophes are further examples of the way Klopstock emphasises feelings not natural objects. The romantic poets would later write of landscapes and natural scenes and project emotions on to them, leading Ruskin famously to invent the term 'pathetic fallacy' for the application of emotions to inanimate objects ('cruel foam', was one of his examples).

In attempting to deal with the emotion directly and not via some natural 'objective correlative', it could be argued that Klopstock was ahead of many of the writers who would come after him. The beauties of Nature are sources of feelings, they do not have feelings themselves.

Fanny

And who was that modern translator's nightmare, the sensitive empathetic 'Fanny'?

That was one of Klopstock's names for his great love at that time, his cousin Maria Sophia Schmidt (1731-1799). His adoration of her was tolerated but not requited and ultimately the union was never to be.

By the spring of 1750, after two years of doggy, poetic devotion, she informed her poet that she could not make up her mind about him: in effect, Klopstock's journey to Switzerland seems to have been as much an attempt to flee from the wreckage of his romantic situation as Goethe's flight to Switzerland would be twenty-five years later in 1775. Goethe was clearing his head of Lili Schönemann, the banker's daughter who would later marry money. Maria Sophia, having been immortalised – sort of – as 'Fanny' (sometimes as 'Daphne', sometimes 'Laura') by the besotted Klopstock would also marry a rich merchant and add some money to her fame. 'Empathetic!' – well, she certainly had Klopstock's number.

Unfortunately, there is more than a little doubt about this attractive interpretion, for when we look at the original, 1750, version of the ode, Klopstock wrote der fühlenden Sch•••inn [Schinzin] gleich, referring to the eighteen year-old Anna Maria Schinz (1732–1811), the sister of Johann Heinrich Schinz, both of whom were passengers on the journey down the lake.

Although, as we shall hear later, a different Anna Maria, Anna Maria Hirzel, the wife of Caspar Hirzel had been assigned to Klopstock as a kind of female cavalier d'honneur for the lonely poet, he soon wisely transferred his affections from the twenty-five year-old married woman to the eighteen year-old Schinz, who had the decided advantage of being single. The two lovebirds even 'exchanged Mäulchen', the 18th century equivalent of 'having a good snog'.

At this point in this first version, therefore, there is no thought of the lost love, Maria Sophia Schmidt, a.k.a. 'Fanny'. Make of that all what you will.

Most of Klopstock's revisions of the 1750 text were intended to correct metrical problems. In this respect der fühlenden Sch•••inn has a big problem: the anonymisation of the name means that there is now a vowel and two consonants missing – so how do we know whether the vowel is long or short? In fact, how do we read it at all – how does one pronounce '•••'? What would Horace say?

— v — v v — v v.

Sanft, der fühlenden Sch•••in gleich!

Sanft, der fühlenden Fanny gleich.

So, twenty years after he wrote the poem, Klopstock solved the metrical problem he had created with his anonymised Sch•••inn by reaching into his poetic toolbox and grabbing his good old standby, the generic 'Fanny'. One thing leads to another, though: Klopstock removed the exclamation mark he had set for the hot eighteen year old, Anna Maria Schinz, and gave the fantasy Fanny a neutral full stop instead. Ah, time – the great passion killer!

Strophe 4: The boat trip

So far the reader has been given only a few vague hints of location. The title The Zurich Lake is one of these; the other is 'vineyards on the banks of the shimmering lake'. In the next strophe Klopstock steps away from empathy, sensitivity and emotion to give us some travel writing at last.

On 24 July this year your author took a trip from Zurich along the Lake of Zurich to the Au Peninsula, the journey made by Klopstock and his young friends on 30 July 1750. Things have changed in two and a half centuries:

Zurich and its lake in modern times. The Uetliberg is the elongated hill that runs down the western edge of the map; the Halbinsel Au, the 'Au Peninsula' is marked by the red circle. A glance is enough to show the density of the settlement along the modern lake shore: uninterrupted building, a motorway and two railway lines on the western bank; the expensive settlements of the 'Gold Coast' on the eastern bank. What else could we expect after 250 years of economic progress?

All aboard the MS Wädenswil at the boat station in Bürkliplatz, Zurich, 268 years after Klopstock and his friends undertook the journey. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Schon lag hinter uns weit Uto, an dessem Fuß

Zürch in ruhigem Thal freye Bewohner nährt;

Schon war manches Gebirge

Voll von Reben vorbeygeflohn.

The broad mass of the Uetliberg already lay far behind us, at the foot of which Zurich in its quiet valley nourishes its free inhabitants; Several hills with vineyards had already fled past us.

'weit Uto', the Uetliberg, – the long hill that stretches out behind the western shore of the Lake of Zurich. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The view from Zürich southwards towards the Alps on a hazy summer day. The view only reaches as far as the bend in the middle of the lake. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

More of 'weit Uto' – still not finished yet. The lake shores on both sides are almost uninterruptedly built on. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

It is at this point that we, too, have to come clean with the reader and supply some down-to-earth information about the context of the poem. What was Klopstock, the poet from north-eastern Germany, doing boating over the Lake of Zurich that summer's day?

Johann Jakob Bodmer

The key figure behind Klopstock's presence in this boat on the Lake of Zurich is Johann Jakob Bodmer (1698-1783), the Swiss philologist, historian and writer.

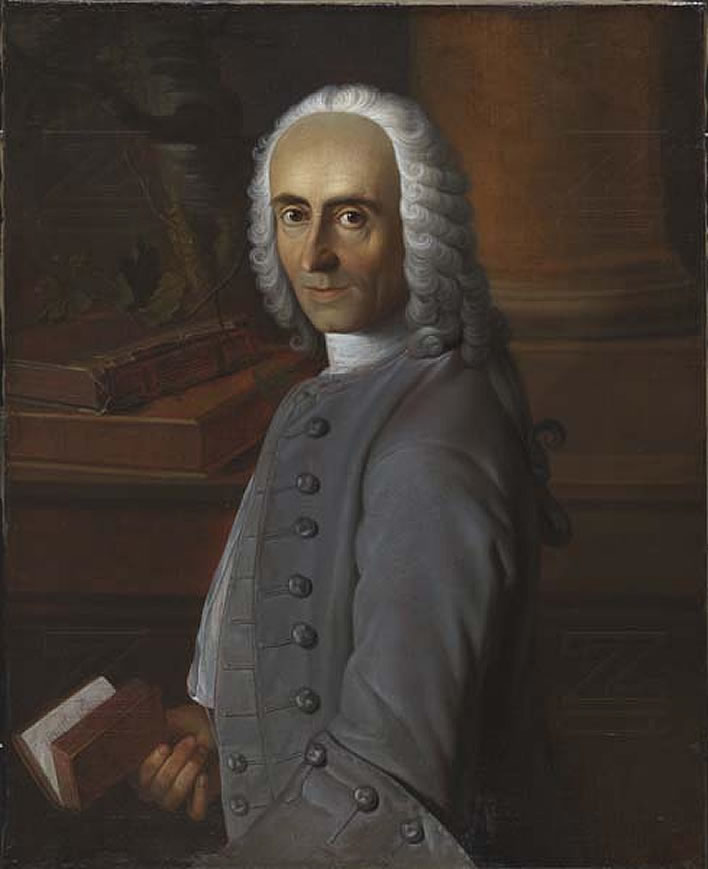

Johann Caspar Füssli (1706–1782), Porträt von Johann Jakob Bodmer, oil on canvas, 1748? Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Bodmer, then in his early fifties, had been supporting and encouraging the young poet half his age from afar through one setback after another. When Klopstock lost the tutoring job in Langensalza (near Erfurt) that had kept him in proximity to the object of his desire Maria Sophia Schmidt – and when the the object of desire herself couldn't really make up her mind about him, Bodmer got to hear of his troubles.

Bodmer offered Klopstock a stay in his house near Zurich so that he could continue working in peace and quiet on his poetical project Messias, the 'Messiah'. Bodmer even sent him 300 Thaler to cover the expenses of the journey.

In May 1750, Klopstock left Langensalza and made his way via various stops with friends to Zurich, arriving on 21 July.

Some relationships are best kept at a distance. That between the fifty-six year old Bodmer (and his circle of equally elderly Swiss academics) and the twenty-six year old Klopstock soon foundered on proximity. Bodmer expected his newly adopted rescue-poet to sit down and get to work on his opus magnum in the quiet of his creaking, almost empty house.

Bodmer's wife was blind, his friends geriatric. Klopstock stared at the blank sheets, toyed with the inkpot, gazed out of the window; the muse occasionally brought him a few lines. He was also expected to listen to Bodmer reading his own work in progress, Noah, and offer helpful criticism. Klopstock's criticism came as sparingly as his own muse.

Johann Jakob Meyer (1749–1829), Bodmerhaus, drawing, around 1780. Splendid isolation: Bodmer's house pictured thirty years after Klopstock's visit. Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Bodmer and Klopstock had quite a lot in common intellectually. Bodmer and his friend Breitinger were also great fans of Longinus and issued their own prescriptions of what constituted the sublime in writing. In sum: the use of the 'noblest' words, the 'refinement' of names, the use of foreign words, the application of daring metaphors, the deviation from normal word order, the resurrection of old and forgotten words, the creation of adjectives concatenated from several other words (following the Homeric example).

Nowadays this list would be taken as a series of bullet points intended to advise people on how NOT to write English (or German, for that matter). But this is the German-speaking world of the mid-eighteenth century, a very distant country, and in almost every line of Der Zürchersee we can find some example of the implementation of one or more of these rules in pursuit of the sublime.

Despite their shared interests, the age gap of a quarter of a century between the two proved to be critical. Goethe had a similar experience when he spent a few months in Strasbourg in the company of that other literary giant, Johann Gottfried Herder: Goethe tells us that 'He was five years older than I, which in youth makes a big difference.'

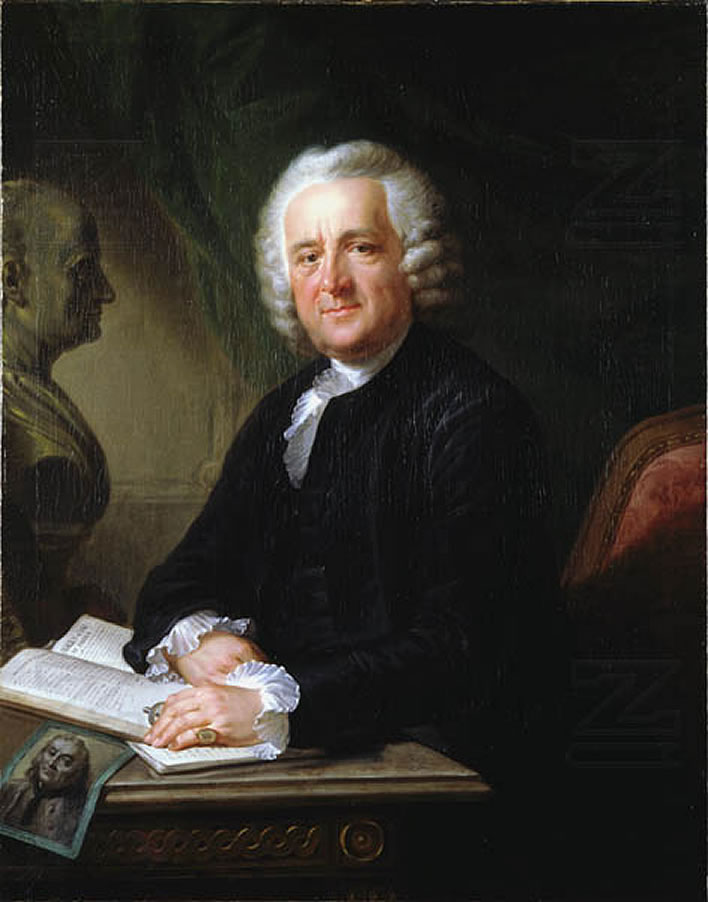

Then the young man fell in with the wrong crowd – wrong, at least as far as Bodmer was concerned: young, high spirited, exciting men and women from Zurich. The leaders of the wrong crowd were the Swiss medical doctor and writer Johann Caspar Hirzel (1725-1803), at twenty-five a year younger than Klopstock, and Hartmann Rahn (1721–1795), the owner of a silk-dyeing business, who was the one who arranged for the boat trip on the Lake of Zurich on 30 July.

Friedrich Oelenheinz (1745–1804), Porträt von Hans Caspar Hirzel, 1790. The solid and now renowned Zurich doctor pictured forty years after the boat trip with Klopstock. Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

The boat trip was not the last of the jollity between Klopstock and his new, young Swiss friends. Bodmer was deeply shocked at the levity of the author of the ponderous Messias –'two people in one body' he called Klopstock. Bodmer's annoyance was fed further by Klopstock's lack of effusive gratitude for his rescue and the provision of his writer's kennel in Zurich; laved by the adoration of his new friends, it seems that Klopstock came to regard Bodmer's help as no more than the young poet deserved. No good deed goes unpunished, then as now.

Wild things

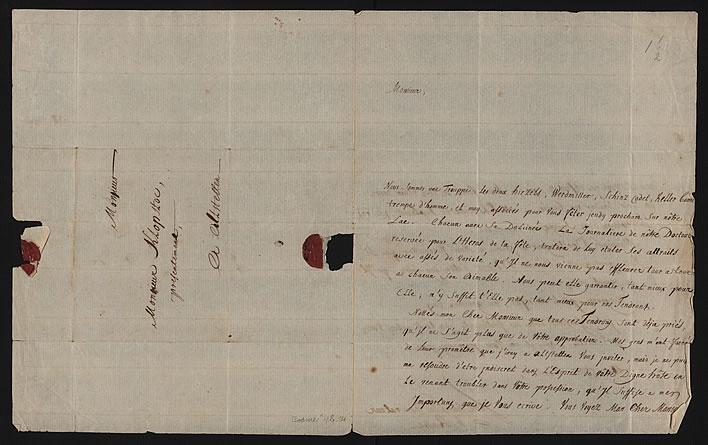

Hartmann Rahn sent the following invitation to Klopstock on 27 July:

Dear Sir

We are a group of people, both of the Hirzels, Werdmiller, the younger Schinz, Keller, a man of good qualities and I, who have got together to celebrate you next Thursday on our lake. Every one will bring his Dulcinea* with him. The lady of our good doctor is intended for the hero of the celebration and will attempt to make her attractions so varied for him so that he does not steal everyone else's sweetheart one after the other. If she can achieve that, so much better for her; if she cannot, so much better for our girls. You should know that all these girls have already been invited and only their agreement is yet to be received. … In God's name no refusal, rather a friendly 'Yes'!…

Mein Herr,

Wir sind eine Gesellschaft, die beiden Hirzels, Werdmiller, der jüngere Schinz, Keller, ein Mann von guter Art, und ich, die wir uns verbunden haben, Sie am nächsten Donnerstag auf unserem See zu feiern. Jeder wird seine Dulcinea mit sich haben. Die Hausherrin unseres Doktors wird für den Helden des Festes bestimmt sein und wird versuchen, ihm ihre Reize so abwechslungsreich wie möglich darzubieten, damit er nicht nach und nach jedem von uns sein Liebstes entführt. Kann sie uns das verbürgen, um so besser für sie; erreicht sie das nicht, um so besser für unsere Mädchen. Sie müssen wissen, mein lieber Herr, dass alle diese Mädchen schon eingeladen sind, und dass es nur noch um Ihre Zustimmung geht. … Um Gottes Willen keine Ablehnung, sondern ein freundliches Ja!…

* Dulcinea = The woman of superhuman beauty loved by Don Quixote in Miguel de Cervantes' novel Don Quixote.

The letter is written in French; this is the German translation supplied by the Zentralbibliothek in Zürich.

Hartmann Rahn's letter inviting Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock to the trip on the Lake of Zurich, 27 July 1750. Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab, 1600 x 1005 px].

We can see why Klopstock preferred the company of this lively band to the dull creaks of Bodmer's house. Fortunately for everyone involved, the two respected elders, Bodmer and Breitinger, refused to come along on the excursion. They must have had a pretty good idea of what would happen.

The proximity of men and women was a radical departure for Zurich, as Klopstock told his friend Johann Christoph Schmidt in a letter written on 1 August 1750:

I can tell you, I have not had so much fun, so uninterrupted, so wild and so much at once as I did on this wonderful day. The company consisted of sixteen* people, half of them female. It is normal here that women rarely speak to men and just visit each other. I was flattered for having brought together such an extraordinary group of people.

We left at five in the morning on one of the largest boats on the lake. The lake is incomparably calm, has pale green water, both banks consist of high hills with vineyards and are completely filled with mansions and country retreats. Where the lake bends, one sees a long row of alps ahead, which stretch up into the heavens. I have never seen such a completely beautiful view.

Johann Jakob Koller (1746–1805), Prospect der Stadt Zürich von der Mittags Seiten auf dem See bey der Claus-Stud anzusehen, Radierung, 1778. Boot traffic on the Lake of Zurich in 1778, around thirty years after Klopstock's journey. The boat his party took was probably similar to the large boat close to the centre of the picture. Koller also caught the marked green cast of the surface of the lake. Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

The markedly green water of the lake. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Continuous dense settlement of this desirable piece of land. Images: ©Figures of Speech.

Still some way to the bend in the lake and our view of the Alps and the Au Peninsula. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Intensive development all the way up the side of the hill at Horgen and beyond. Images: ©Figures of Speech.

More lakeside civilisation. Images: ©Figures of Speech.

We are not clear of civilisation yet, on both sides of the lake. This is Horgen. Images: ©Figures of Speech.

After we had been travelling an hour we breakfasted at a country house on the edge of the lake. Here the company spread out and got to know each other fully. Dr Hirzel's wife, young with very expressive blue eyes, who recited Haller's Doris incomparably wistfully, was the first lady of the company; you understand, because she was assigned to me. I was, however, soon unfaithful to her.

Ich kann Ihnen sagen, ich habe mich lange nicht so ununterbrochen, so wild und so lange Zeit auf Einmal, als diesen schönen Tag gefreut. Die Gesellschaft bestand aus sechzehn Personen, halb Frauenzimmer. Hier ist es Mode, daß die Mädchens die Mannspersonen ausschweifend selten sprechen, und sich nur unter einander Visiten geben. Man schmeichelte mir, ich hätte das Wunder einer so außerordentlichen Gesellschaft zu Wege gebracht.

Wir fuhren Morgens um fünf Uhr auf einem der größten Schiffe des Sees aus. Der See ist unvergleichlich eben, hat grünlich helles Wasser, beide Gestade bestehen aus hohen Weingebirgen, die mit Landgütern und Lusthäusern ganz voll besäet sind. Wo sich der See wendet, sieht man eine lange Reihe Alpen gegen sich, die recht in den Himmel hineingränzen. Ich habe noch niemals eine so durchgehends schöne Aussicht gesehen.

Nachdem wir eine Stunde gefahren waren, frühstückten wir auf einem Landgute dicht an dem See. Hier breitete sich die Gesellschaft weiter aus und lernte sich völlig kennen. D. Hirzels Frau, jung, mit vielsagenden blauen Augen, die Hallers Doris unvergleichlich wehmüthig singt, war die Herrin der Gesellschaft; Sie verstehen es doch, weil sie mir zugegeben war. Ich wurde Ihr aber bey Zeiten untreu.

* Klopstock is mistaken, there were actually 18 passengers.

The puritan city

Zurich at that time was still a place that took its Protestantism seriously – let us not be fooled by the easy-going, worldly liberalism of the modern city.

Two centuries before Klopstock's gentle journey over the shimmering waters of its lake, Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) had introduced the city to the Reformation with powerful words; when these failed, fire and the sword were at hand.

Zwingli himself fell in the battle of Kappel am Albis, waged against the Catholics of central Switzerland. 'Fell' is a euphemism here: he was captured, mocked and then brutally killed. His corpse was cut into quarters, which were then burnt and the ashes scattered to the winds – the gentle west winds that could easily carry them the five kilometres to the Au Peninsula, the sylvan paradise towards which Klopstock and his young friends were heading on this morning.

The next generation of Protestant reformers, Johannes Calvin (1509-1564) in Geneva and Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575) in Zurich, followed in Zwingli's footsteps and consolidated his work. All pleasures of the body and of the mind were removed from life: the pictures in the churches were taken down (the removal of the altar pieces in the Grossmünster in Zurich was Zwingli's doing); relics were removed or destroyed (Bullinger removed the remains of the two martyred saints of Zurich, Felix und Regula). A fierce, unfliching, unremitting, Calvinist morality descended over the city.

It was still there, if not so extreme, in 1750, when Klopstock was there: the whole armoury of the Protestant Ethic – work and introspective moral purity – was, though slightly faded, still there; an ethic that we see in Bodmer's disappointment over the lax lifestyle and missing work-ethic of his dissolute guest from the north.

In this context we may recall Goethe's remarks at the offence taken by the locals at the skinny-dipping antics of the Stolberg brothers during their passage through Zurich twenty-five years after Klopstock's boat trip.

Thus in the strict moral atmosphere of Zurich we are not surprised that young men and women kept themselves apart and that the boat trip itself became an object of scandal and gossip among the locals and certainly not surprised that Bodmer and Breitinger kept their distance.

Strophe 5, 6: The companions; anacreontics

Jetzt entwölkte sich fern silberner Alpen Höh,

Und der Jünglinge Herz schlug schon empfindender,

Schon verrieth es beredter

Sich der schönen Begleiterin.

Now the clouds cleared from the distant peaks of the silver Alps and the hearts of the youths beat more receptively, the beautiful companion had already betrayed it in words,

At last we round the corner and get a view of the Au Peninsula and a suggestion of the distant Alps through the haze. When a Föhn wind is blowing, as it often does in autumn, we would be able to see the snowy peaks much more clearly. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The fifth strophe opens with a continuation of the report of the journey as it flows past, introduced simply with 'now'. The travelogue does not last beyond this first line, because once more we move into the region of the senses and their sensibilities that generate feelings.

The metaphor is unmissable: as the Alps come into view and the clouds clear from their silver tops, so the humans in the boat experience the transition to the perception of those things of bright excellence, Spinoza's rare praeclara.

Approaching the Au Peninsula, the Alps still just a hazy suggestion. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Once again, the process leading to the sublime emotion that was described in the first strophe is held before us: the beauty of Nature is exceeded by the beauty of the feelings and emotions which it calls up in its human observers.

In the first strophe that process was betrayed (in the sense of 'made manifest') by the joyful face, now 'the hearts of the youths beat more receptively'. The process is betrayed ('made manifest') in particular by Klopstock's 'beautiful companion', Anna Maria Hirzel (1725–1790, née Ziegler), Dr Caspar Hirzel's wife. Her betrayal was beredter, 'more eloquent' (one of Klopstock's 'sublime' words), and the details of it are given in the next strophe.

Hallers Doris, sie sang, selber des Liedes werth,

Hirzels Daphne, den Kleist zärtlich wie Gleimen liebt,

Und wir Jünglinge sangen,

Und empfanden, wie Hagedorn.

She sang Haller's Doris, worthy herself of the song, she, Hirzel's Daphne, [Hirzel] who was loved tenderly by Kleist as much as Gleim, and we young men sang and felt as Hagedorn [did].

In Klopstock circles, this strophe is known as the 'literary strophe', for obvious reasons: Klopstock packs into its four lines allusions to five writers – steep rock for those ascending his sublime mountain.

Two are from an earlier generation: Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777), a Swiss scientist and poet and Friedrich von Hagedorn (1708-1754), a German poet, both of whom were still alive in 1750. The other three are from Klopstock's generation (1724-1803): Ewald Christian von Kleist (1715-1759), a German poet and soldier; Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim (1719-1803), a German poet and Johann Caspar Hirzel (1725-1803), a Swiss doctor and writer whom we have already met – Hirzel, of course, was part of the lake journey, as was his wife, Anna Maria.

Ewald von Kleist died a noble – though extremely unpleasant – death on the battlefield fighting for the Prussians, in one of those pointless 18th century conflicts that achieved nothing apart from the increase of human misery.

What can possibly unite these five people?

Hirzel, Kleist, Gleim and Klopstock are contemporaries united in friendship, but there is a literary bond between all of them: anacreontic poetry. This is poetry easily characterised as 'wine, women and song / eat, drink and be merry etc. for tomorrow we may die'. It is called anacreontic after its celebrated early practitioner, the Greek poet Anacreon (c.582-485 BC).

Hagedorn and Gleim founded their poetic fame on anacreontic verse, Gleim even becoming known as the 'German Anacreon'; Kleist wrote anacreontics amongst other works such as pastoral idylls.

Haller was one of the great polymaths thrown up in that century, when it was still possible for a single person to know nearly everything that was known. The poem of his that is explicitly mentioned here, Doris, he wrote in 1730 when he was 22 years old, that is, nota bene, merely 20 years before Klopstock's journey on the Lake of Zurich.

It is a magnificent poem of astonishing subtlety that was deservedly popular in its time. (I intend to discuss the poem in October this year, the 310th anniversary of Haller's birth). Haller's Doris is a long way away from the boozy cheerfulness we expect of anacreontics, but it is as strongly affirmative to life and love as they are. From Klopstock's strophe as well as the letters we have, it seems that Anna Maria Hirzel could turn in a particularly fine rendering of Doris. A little puzzling, for if ever a poem required a male speaker, it is that one.

In the boat, Klopstock is in the middle of a circle of cultured, literate young people, with whom he now identifies as 'we young men'.

Anna Maria Hirzel is identified as Hirzel's 'Daphne'. Klopstock occasionally used 'Daphne' as an alternative reference to his own beloved, the woman we met in this poem as 'Fanny'. The mythological allusion is to the Daphne who was the object of desire of the god Apollo, the god most associated with lyrical verse. In order to escape from Apollo's advances she was transformed into an laurel bush, hence the association of the laurel wreath with artistic accomplishment. Klopstock has styled the woman after whom the latter-day Apollo lusts – whether Klopstock himself or Hirzel – as his Daphne.

In Klopstock circles there has been some debate on what to do with Hallers Doris: should it be Hallers 'Doris', or even 'Hallers Doris'. German schoolteachers are always keen to 'improve' the orthography and grammar of their nation's poets. However, Klopstock in his first, 1850, version of the text wrote Hallers Doris and in his 1771 revision, despite making some small corrections in its vicinity, left it like that – a hint which should be good enough for us plodders. Besides, messing about with such marks ruins the fine visual, aural and metrical symmetry of Hallers Doris and Hirzels Daphne.

— v — v

Hallers Doris,

Hirzels Daphne,

Standing back from all the many details, we see that the 'literary strophe' presents the reader in intensely compressed form with a nexus of the two generations of anacreontic poets of the time. There is much more we could say, but we won't: the boat glides onwards!

Strophe 7: The joy of arrival on the Au Peninsula

Jezt empfing uns die Au in die beschattenden

Kühlen Arme des Walds, welcher die Insel krönt;

Da, da kamest du, Freude!

Volles Maasses auf uns herab!

Now the Au received us in the shaded cool arms of the woods that crown the island; there, there you came, Pleasure! In full measure down onto us.

Approaching the boat station on the Au Peninsula. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Mooring and disembarcation. The MS Wädenswil will continue on its tour of the lake, back up the eastern shore until it returns to Zurich. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The passenger access from the boat station is essentially the route up to the restaurant and hotel on the crown of the hill – business is business! Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Landfall

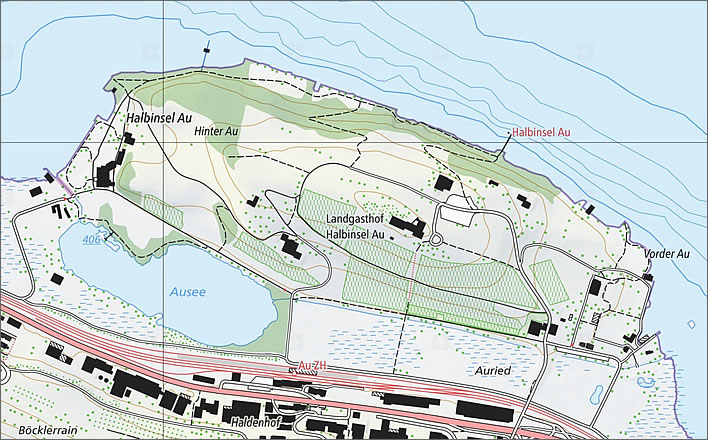

The Au Peninsula is a small intrusion of land from the southern shore into the Lake of Zurich about 15 km from Zurich.

Satellite view of the Lake of Zurich. The Au Peninsula is marked with the red circle. Image: Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo.

The term 'peninsula' may seem a bit misleading, since at its furthest point it only extends by about 500 metres out from the shoreline. In effect, the peninsula is an elongated hump about one kilometre in length that runs parallel to the lake shore, to which it is connected by a low lying strip of land, complete with its own small lake, the Ausee.

Aerial view of the Au Peninsula. Image: Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo.

Aerial photograph of the Au Peninsula. Image: Schloss Au Tageszentrum.

The gentle slopes at the western end of the hump are called the Hinter Au, the 'rear Au'; in the middle the hill of the Au itself rises at its peak to 50 metres above the level of the lake; the lower land at the eastern end of the peninsula is the Vorder Au, the 'front Au'. For the curious: the flow of water in the lake is north-westwards from the mountains towards Zurich, where it disgorges into the river Limmat, which is why the south-eastern end of the Au is the 'front' and the south-western end the 'rear'.

The southern flanks of the hill are today covered with vineyards, the western flanks with hill grazing and orchards, the steep northern slopes are wooded.

The northern shore of the Au is one of the most popular diving spots in Switzerland. Klopstock and his party probably had no idea that a few metres out from the water's edge there is an almost sheer drop – a wall, overhanging at some points – that plunges straight down to a depth of nearly 100 m.

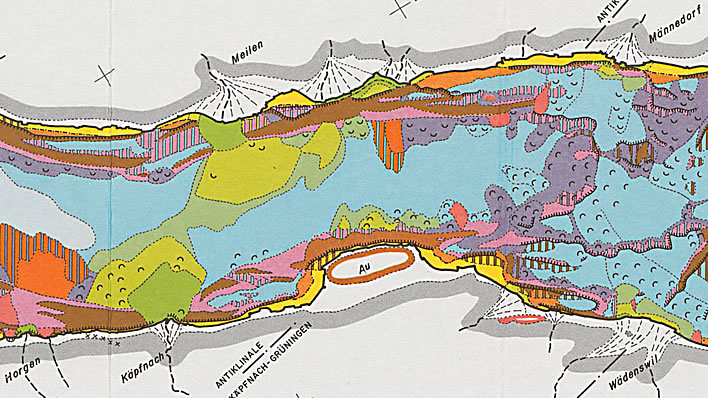

An excerpt from the geological map of Switzerland showing the Au as a pillar of Nagelfluh conglomerate from the terminal moraine left behind by a glacier from the Würm glaciation, the last glacial period in the region (between c. 115,000 and c. 11,700 years ago). The question of why this outcrop of relatively soft material has managed to defy thousands of years of erosion is still a mystery. Its near vertical face under water is pitted with caves.

The Nagelfluh which forms the Au is an aggregate of stones embedded in compacted sand. The material was laid down by the intermediate terminal moraine of glacier during the last great ice age. The rock is riddled with short caves.Image: ©Figures of Speech.

In the intervening centuries the Au Peninsula has changed nearly as much as the other parts of the shoreline of the Lake of Zurich. True, it has not been massively built over but we still need to use our imagination to visualise the way it appeared to Klopstock and his friends.

We have to imagine away the modern monstrosity of the restaurant on the summit of the hill: that was first built in 1865/66 and has been extended over the years until it has become today's mass catering canteen for well heeled tourists. (8.50 CHF for one dl (one!) of mediocre Europlonk. Figures of Speech recommendation: sandwiches and a flask.)

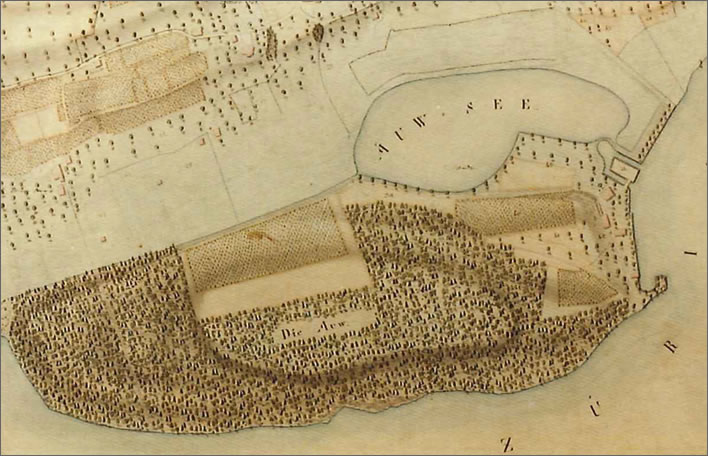

A map of the Au from 1830 (NB: north is down) showing the extent of the original woodland, vineyards and (presumably) orchards. There is no trace of a landing site shown, except for the harbour-like structure on the right (west).

The forest supplied wood for the nearby town of Wädenswil. The farmhouse that has now become the Weinbaumuseum, 'Viniculture Museum' was built in 1835, at the same time that the then owners of the Au cleared much of the woodland. This was a decisive moment that shaped the appearance of the peninsula for ever.

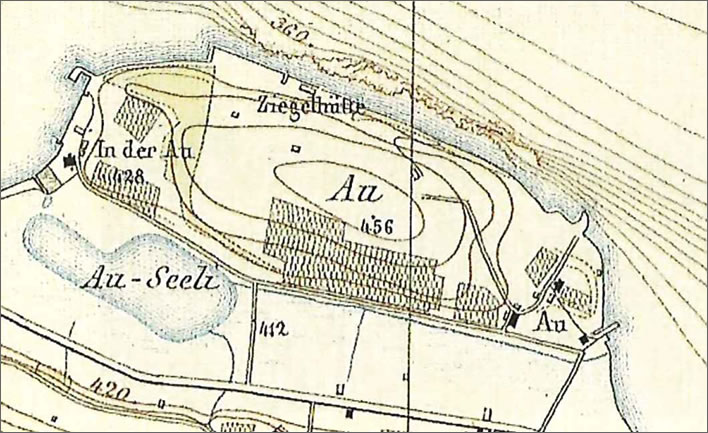

A map of the Au from 1850, twenty years after the previous map and showing the dramatic results of the deforestation that began in 1835, which left the peninsula with a strip of woodland along the steep, agriculturally useless shore slopes. A number of tracks have been built and the farmhouse, also built in 1835, can be seen in the intersection of the tracks on the righthand side of the peninsula. This is now the viniculture museum.

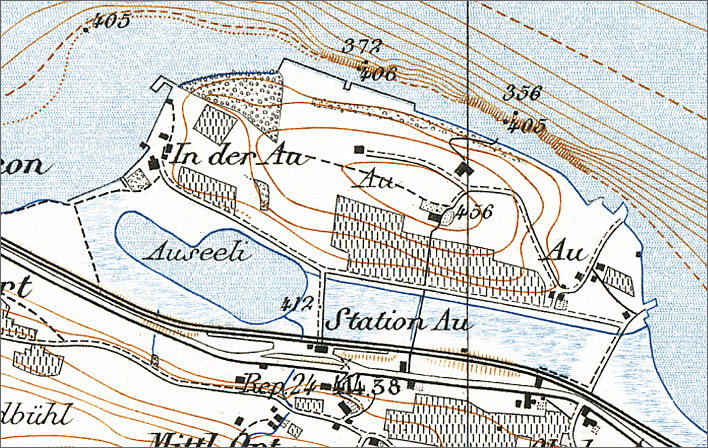

A map of the Au from 1884. The summit of the hill has been colonised (from 1865) and another farmhouse has been built in the intersection of the summit tracks. The miserable remains of the former wood along the shoreline are clearly indicated.

Whereas Klopstock's party would have found a dense oakwood that covered most of the hill, interspersed with occasional glades, today's visitor sees only meadows and clumps of trees – the narrow strip of woodland on the steep slope of the northern shore is all that is left of the original forest.

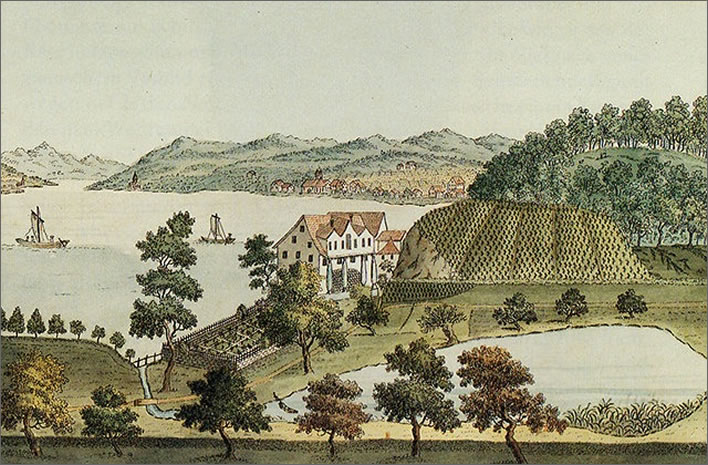

At that time the only substantial structure on the peninsula was the country house on the Hinter Au built by Colonel Johann Rudolf Wegmüller in 1650. That building was demolished and replaced by the present day mock baroque Schloss in 1928/29. The modern landing place for the ship traffic was not there then, of course, nor were many of the paths and roads we find today.

Heinrich Brupbacher (1758–1835), L'Au-presqu'Isle au bord du Lac de Zurich avec ses Environs vers l’occident, 1794. Colonel Wegmüller's country house in 1794, showing one of his passions, his garden, the extensive vineyards and the wooded crown of the central hill. Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

The modern situation would be much worse, had not the Au-Konsortium been founded in 1911, which bought up the land in order to keep it in its natural state. At that time property speculators and mega-rich individuals were circling the Au with development plans. There is no doubt that without the intervention of the Consortium the Au would today look much like the rest of the shoreline: row upon row of expensive apartment blocks. Despite this apparent conservation and apart from a few surviving oak trees, almost nothing on the Au is as it was in Klopstock's time.

A modern map of the Au Peninsula. Wanderland.

Colonel Wegmüller, who bought the Au and built his country house there, was a remarkable and fascinating figure – 'colourful' is the usual word. During his time there the Au gained a reputation among the upright citizens of Zurich as a place of dissolution and scandal. It seems not unlikely that even in Klopstock's time the Au still had the seductive fragrance of the disreputable that might have stirred the interest of our enlightened youngsters as a destination for their excursion. It should not surprise us that a mixed-sex, unchaperoned party of eighteen young people heading off in a boat for a day on the Au would have caused tongues to wag in the city of Zwingli.

Aerial photograph of the present day 'Schloss'. Image: Schloss Au Tageszentrum.

The boat house of the present day 'Schloss'. Image: Schloss Au Tageszentrum.

For Klopstock's young group, arriving on the Au must have had much the same liberating effect that visiting foreign countries has for the young of our day. Perhaps we should keep this in the mind when reading the cries of joy and happiness that fill the next three strophes.

Strophe 8: The goddess of Pleasure

Göttinn Freude! du selbst! dich, wir empfanden dich!

Ja, du warest es selbst, Schwester der Menschlichkeit,

Deiner Unschuld Gespielinn,

Die sich über uns ganz ergoß!

Goddess Pleasure! your very self! we felt you! Yes, it was you indeed, sister of Humaneness, your innocent playmate, who flowed over us completely!

In Klopstock's time these areas would have all been mostly wooded. These clearings were created by the drastic deforestation around 1835. Image:©Figures of Speech.

If there is one single strophe that is a rejection of Bodmer, Breitinger and the geriatric Zwingli-culture of uptight Zurich it is this. The strophe is a validation of the nobility of the existence of Pleasure, in allegorical partnership with her sister, Humaneness. The need to validate the acceptability of enjoyment, of pleasure, we discussed in the context of another writer and artist damaged by Pietist brainwashing, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739-1791).

Klopstock now goes on to consider some of the causes of pleasure.

Strophe 9, 10: The sweetness of love

Süß ist, fröhlicher Lenz, deiner Begeistrung Hauch,

Wenn die Flur dich gebiert, wenn sich dein Odem sanft

In der Jünglinge Herzen,

Und die Herzen der Mädchen gießt.

Sweet is, joyful spring, the breeze of your enthusiasm, when the land gives birth to you, when your breath is poured softly into the hearts of the young men and the girls.

This strophe is interesting for the way in which Klopstock does not directly mention love, but merely implies it in his description of the stimulating effect of springtime. Once more we find Klopstock avoiding the abstract term by using an allegorical figure representing a material and emotional reality – an 'objective correlative', if you will.

Ach du machst das Gefühl siegend, es steigt durch dich

Jede blühende Brust schöner, und bebender,

Lauter redet der Liebe

Nun entzauberter Mund durch dich!

Ah, you make feelings triumph, through you every flowering breast grows more beautiful and more trembling, the mouth released from its spell by love speaks louder through you.

Strophe 11, 12: The pleasure of moderate intoxication

Lieblich winket der Wein, wenn er Empfindungen,

Bessre sanftere Lust, wenn er Gedanken winkt,

Im sokratischen Becher

Von der thauenden Ros' umkränzt;

The wine sweetly beckons when it [offers] sentiments, [offers] better, gentler desire, when it offers thoughts, in the Socratic cup crowned by the dewy rose.

The modern English speaker will need to disentangle the knot of Klopstock's complex imagery here. It helps parsing this strophe if we bring together what should really never have been separated, that is: Lieblich winket der Wein … Im sokratischen Becher, 'The wine sweetly beckons … in the Socratic cup'. The strophe is a plea for moderation in the consumption of wine. The expression the 'Socratic cup' is an allusion to the advice given by Socrates in Xenophon's Symposium to use small wine cups to avoid inebriation:

If we pour ourselves immense draughts, it will be no long time before both our bodies and our minds reel, and we shall not be able even to draw breath, much less to speak sensibly; but if the servants frequently 'besprinkle' us – if I too may use a Gorgian expression – with small cups, we shall thus not be driven on by the wine to a state of intoxication, but instead shall be brought by its gentle persuasion to a more sportive mood.

Xenophon Symposium, chapter 2, section 26.

The 'dewy rose' tells us that it is the morning, and hints that the drinker has survived the night without inebriation. The coronal of roses does not crown the cup, but the drinker. The rose is a traditional symbol for sex.

The wine that has lifted up Klopstock's emotions on this occasion may very well have come from the vineyards on the Au. Wine had been produced on the south slop of the hill since the 1400s at least. In 1912 the 'conservers' of the Consortium gave up wine growing as commercially unviable and dug up the vines. The line between conservation and exploitation is clearly a blurred one.

The vineyard the visitor sees today started to be laid down in 1952 as a research and test location for the Wine Technology department of the University of Applied Sciences. Today's visitor sees more than 180 varieties of grape growing on these slopes. Romance is dead, or at least certainly is not to be found here: the old vertical rows of staked vines have given way to modern horizontal terraces with vines on wires and the grapes are harvested completely automatically by mechanical devices.

Wenn er dringt bis ins Herz, und zu Entschliessungen,

Die der Säufer verkennt, jeden Gedanken weckt,

Wenn er lehret verachten,

Was nicht würdig des Weisen ist.

when it [the wine] penetrates to the heart, and to decisions which the drunkard misjudges, awakens thoughts, when it teaches contempt for that which is not worthy of the wise.

Strophe 11 and 12 are constituted of a single sentence. Strophe 11 was the first arc of that sentence, ending with a semicolon. Strophe 12 continues the sequence of 'if/when' clauses ('protases'). In order to understand the statements of strophe 12 correctly we need to prefix them with the introductory clause (the 'apodosis', the consequence) from the beginning of Strophe 11: 'The wine sweetly beckons' … when it penetrates to the heart …, when it teaches contempt for the unworthy…

Strophe 13, 14, 15: The pleasure of fame and approval

Reizvoll klinget des Ruhms lockender Silberton

In das schlagende Herz, und die Unsterblichkeit

Ist ein grosser Gedanke,

Ist des Schweisses der Edlen werth!

Attractively clinks the seductive silver tone of fame in the beating heart, and immortality is a great thought, is worth the sweat of the noble ones!

The 'seductive silver tone' is the sound of silver coins chinking; 'the beating heart' is a synecdoche for a 'living person', for whom 'immortality is a great thought'.

Durch der Lieder Gewalt, bey der Urenkelinn

Sohn und Tochter noch seyn; mit der Entzückung Ton

Oft beym Namen genennet,

Oft gerufen vom Grabe her,

Through the power of poetry, which is still present for the son and daughter of the great-grandchildren; the poet's name often spoken in a tone of delight, often called up from the grave,

Dann ihr sanfteres Herz bilden, und, Liebe, dich,

Fromme Tugend, dich auch giessen ins sanfte Herz,

Ist, Goldhäufer! nicht wenig!

Ist des Schweisses der Edlen werth!

then to form their receptive hearts and to pour Love, You, and Pious Virtue, You, into the gentle heart is, goldgrubber(s)!, not a little thing! It is worth the sweat of the noble ones!

These two strophes present the reader and commentator with formidable parsing problems. The superficial problems are aggravated by our knowledge that Klopstock, in 1750, began the strophe with the conjunction Da, 'since/because', a usage which is obscure to the point of pitch blackness. Perhaps realising this, or perhaps for the weak euphony of neighbouring vowels, Da ihr, and the metrical problems which that creates he changed this to the adverb Dann, 'afterwards', in his 1771 edit, replacing the obscure with the incomprehensible.

The original translation has been much improved thanks to a German gloss sent in by Lars Bardram in the comments. We are dealing with Klopstock here, so the present effort may not be the last word. On his deathbed your translator will cry out: 'Klopstock! What on earth does strophe 14 mean?' 'Patience, my child', says the angel with the darker draught, 'You'll be able to ask him yourself in a moment'.

An attempt at a paraphrase might give us: The power of your poetry can ensure that you will be fondly remembered down the generations. Your thoughts and imagination – love and pious virtue – will mould the receptive minds of your descendants. That is not a little thing, it is worth more than money and worth the effort of the noble mind.

This strophe has even more mystery for us. In 1750 Klopstock wrote Ist, beym Himmel! nicht wenig!, 'is, by heaven! not a little thing'. It is possible to read what seems to be on the surface an everyday expletive as meaning 'in the sight of heaven', but the phrase hardly meets Klopstock's criteria for sublime diction. In 1771 he changed it to his specially created word Goldhäufer, literally 'those who heap up gold'. The new word adds a tone of personal invective directed at others that is unique in the poem.

Strophe 16, 17, 18, 19: Friendship, the sweetest pleasure

The previous four groups of strophes we characterised as being thematic units: love, intoxication and fame. They are forms of pleasure that are the specifics of the general theme of the validity of pleasure and humaneness that was stated in strophe 8.

They are part of a large rhetorical structure which now comes to completion. Each of the first three units was introduced by an adjective or adverb representing some source of pleasure:

- 9, 10: Süß, 'sweet' [love].

- 11, 12: Lieblich, 'lovingly' [intoxication].

- 13, 14, 15: Reizvoll, 'attractive' [fame].…

We realise now the great importance of strophe 6, the literary strophe. The list of anacreontic writers we were given there – those writers of passion, love, intoxication and enthusiasm – was a signal to us: in strophes 7-15 Klopstock has written his own anacreontic verses. Those strophes are anacreontic poetry that is more thoughtful, more complex and much more subtle than is usual in the genre. Only Albrecht von Haller, in his masterful poem Doris, cited specifically by Klopstock, achieved this high philosophical level.

The American poet Ezra Pound asserted that every great work of art was a criticism of some other work of art – 'criticism' being meant here in the literary, not simply the negative sense. If we wanted to make the present article – God forbid – three times longer than it presently is we might follow this rabbit down its hole: could we argue that Klopstock's analysis of the traditional anacreontic pleasures is a thoroughly critical analysis, a thesis that sets us readers up for the antithesis and its resolution that comes in the next four strophes? We could, but let's move on – 'But at my back I always hear / Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near', as an English anacreontic poet once put it.

Having given his reader a review of anacreontic verse, now, in strophe 16, Klopstock works all three categories into a comparative construction that puts friendship above all those secondary pleasures:

- 16: Aber süsser ists noch, schöner und reizender, 'But even sweeter, more beautiful and more attractive' [friendship].

Even a poet of Klopstock's skill gets into a bind now and again: in strophe 11, the precision of lieblich, 'loving, gentle', a word frequently applied to wines that are not sour or dry, but not sweet – perhaps halb-trocken– is perfect in its context. In the comparative statement that opens the final group, though, there is no way to get lieblicher to fit into the metrical scheme. Klopstock comes up with the generic schöner, 'more beautiful'. He must have struggled with that important construction for some time.

Aber süsser ists noch, schöner und reizender,

In dem Arme des Freunds wissen ein Freund zu seyn!

So das Leben geniessen,

Nicht unwürdig der Ewigkeit!

But still sweeter, more beautiful and delightful, in the arm of the friend to know you are a friend! In this way to enjoy life, not unworthy of eternity.

The path that runs along the lake shore of the peninsula through the thin strip of forest which is all that is left of the woodlands that Klopstock saw. Pleasant enough, but the trees are now all mundane varieties. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

More pleasant shoreline woodland. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

This notch in the shore was used as a loading and unloading place. Whether it was the point of Klopstock's arrival is not known. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

An oak at last, and quite an old one at that. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

17, 18, 19: The absent friends

Treuer Zärtlichkeit voll, in den Umschattungen

In den Lüften des Walds, und mit gesenktem Blick

Auf die silberne Welle,

That mein Herze den frommen Wunsch:

Full of true tenderness, in the shadows in the airs of the wood, looking down at the silvery wave my heart expressed the pious wish:

Wäret ihr auch bey uns, die ihr mich ferne liebt,

In des Vaterlands Schooß einsam von mir verstreut,

Die in seligen Stunden

Meine suchende Seele fand,

If only you were with us, you who love me from afar, separated from me, alone in the lap of the Fatherland, [you] who in blessed hours my searching soul found,

Strophe 18 in its entirety is the protasis, the 'if' clause of a hypothetical, 'second conditional' sentence. Strophe 19, the last strophe of the poem, is its apodosis, its hypothetical consequence. It is important to be clear about the subject of the sentence, which is in fact the circle of Klopstock's friends that he has left behind in Germany. This group may or may not include his distant love Maria Sophia Schmidt, at that moment a long way away in Langensalza – we hear nothing directly of her.

Klopstock also uses the phrase bey uns, 'with us', presumably meaning 'us' to include his new friends from the boat trip. Klopstock made substantial changes to the 1750 version of this strophe, one of which was to introduce bey uns.

Fruit was grown on the Au in Klopstock's time. The fruit trees of today don't appear to be clustered in orchards but are dotted alongside some of the tracks. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

A view down to the 'castle' of 1928. Could this be the 'vale' leading to the sea that Klopstock imagined would become Tempe or Elysium? Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Another view of the 'castle' of 1928. The building now houses a training institute owned by the Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich.

O so bauten wir hier Hütten der Freundschaft uns!

Ewig wohnten wir hier, ewig! Der Schattenwald

Wandelt' uns sich in Tempe,

Jenes Thal in Elysium!

Oh so we would build here the huts of our friendship! For ever we would live here, for ever! The shady wood would transform itself for us into Tempe, that valley in Elysium!

As already noted, the final strophe is the apodosis, the consequence of the desired hypothetical condition set out in the previous strophe, that his close friends from Germany should also be here on the Au Peninsula.

The huts of friendship

Hütten der Freundschaft, 'huts of friendship' – what a remarkable expression! Its very originality has driven commentators to find some source for it. As a result, an exegetical tradition has been established that the word Hütten is an allusion to the biblical episode of the Transfiguration of Jesus.

The event is described in various ways in Matthew 17:4 (the most extensive description), Mark 9:5 and Luke 9:33. The disciples, on a hilltop, have witnessed the radiance of Jesus and seen him joined by Moses and Elias. The key element in the allusion is Peter's proposal to build three Hütten, as they are called in the Luther Bible. The Authorised Version calls them 'tabernacles', one of those strange terms that no child who underwent a Christian upbringing ever understood or ever forgot – modern English translators go for something like 'tents', the profane might think of 'sheds'.

An allusion to an external text, however, must link the current text with the external text through some shared aspects – a single word is not enough. The allusion has to bring something with it that illuminates or extends the current situation in some way.

Try as you might you will find nothing in the Transfiguration stories that has any relevence to Klopstock's current situation on the Au Peninsula. The absence of Jesus, Moses and Elias, for whom the three 'tabernacles' were to be built, the radiant transfiguration of Jesus – there is nothing here like it. The Bible story is dissonant in this context.

Sometimes a word is just a word: in the Grimms' great Deutsches Wörterbuch you will find enough entries for Hütten to keep you busy for a long time. None of them references the Transfiguration story, showing how slender the association of the word Hütten with that story is in real German usage.

Your author therefore proposes, against the exegetical tradition, that Klopstock's wonderful Hütten der Freundschaft are just that, 'huts of friendship', allegorical, not necessarily physical structures, – places where similarly-minded young friends can hang out, far away from the real world. Being pedantically textual for a moment, we might read the phrase literally: 'huts of friendship', that is, huts consisting of friendship, not huts for friendship – there is a difference.

We don't know without further research, but it seems not unlikely that Colonel Werdmüller, for his country house, his Lustschloss, not only created buildings for his gardens, his winemaking, his fishing and his smithy but also scattered a few huts around in the shady woods for the pursuit of rustic pleasures. Klopstock may have seen real examples of the Hütten der Freundschaft during his sojourn on the peninsula.

The literary paradise

It would be strange, too, if Klopstock had really been referring to this extremely highly-charged moment in the Christian story, because his next step in the strophe is to project a classical image for the location of these huts. The proponents of the Transfiguration allusion have to explain how the Biblical tents now appear in the Graeco-Roman heathen landscape of Tempe and Elysium.

In the 1750 version of this strophe the Schattenwald, the 'shady wood' is merely renamed Tempe, and diese Thäler, 'these valleys' (NB: plural), Elysium. In 1771 the magic is stronger: the woods are transformed into Tempe and 'that valley' into Elysium.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), Story of Apollo and Daphne, exhibited 1837. Tate Gallery. [Click the image to display a larger version in a separate tab, 1536 x 829 px.]

Klopstock's free and easy use of Greek locations should be a warning to us not to take the substance of his literary longings too literally. The 'shady wood' would transform itself for them into Tempe – a transformation which puzzles the purists who remember Tempe – both in Greek myth and nowadays – as a steep sided valley or gorge, traditionally associated with Apollo and Daphne. At its eastern end it opens out into the Aegean Sea, which might be slightly reminiscent of the situation on the Au Peninsula.

The purists are puzzled even more when 'that valley' transforms itself into Elysium, which is a mythological plain, sometimes associated with the Islands of the Blessed, a place where, in classical mythology, the good reside after death. Hence, presumably, Klopstock's rather hysterical repetition of 'for ever'.

Those troubled by the need for two places to accommodate Klopstock's friends in their huts may take some comfort in the association of Tempe with Apollo and literature. The might also recall that Klopstock's life at that time was a struggle that might make him wish for the calm recognition of Elysium, where Yeats' 'golden codgers' could lie around all day in sweet idleness. It would only be a short while before Bodmer would start demanding his money back from the feckless Klopstock.

Conclusion

The MS Helvetia takes from the Hütten der Freundschaft on the Au Peninsula back to the seething Babylon of Zurich.

The view from the boat station back towards Zurich, which is invisible beyond the bend of the lake. Out of sight, out of mind. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The MS Helvetia arrives at the boat station of the Au Peninsula. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Leaving the Au Peninsula. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Just before the boat station in Zürich. In the background the distinctive twin towers of the Grossmünster right of centre. Just left of centre the long pointed spire of the Fraumünster and to the left of that the spire of the Church of St Peter. The view is not all that different to the one we saw in Johann Jakob Koller's view of the city done in 1778, 240 years ago. Image: ©Figures of Speech.

On this visit we have beaten our heads against the complexities of Klopstock's 'sublime' style, one that is quite in keeping with the Protestant Ethic, which demands unceasing labour from whose who would be among the chosen ones.

It is an amusing irony to find this dogged work-ethic applied to the production of carpe diem anacreontics praising wine, women and song, but there it is.

Attaining the things that are praeclara requires labour that is difficilia, not just on the part of the poet but on the part of his despairing reader. The poetic works that attain this radiance are rara, as are the readers who are prepared to labour to unfold patiently the poet's perfect origami and then iron the sheet flat until what is written upon it becomes legible.

As the literary critic Rolf Vollmann once put it in Die Zeit:Sonst liest ja kein Mensch mehr Klopstock, 'No one reads Klopstock any more'.

He went on to point out that one of the greatest difficulties we moderns have with poetry from previous centuries – and with Klopstock in particular – is that we can no longer express the emotions we meet – our language, whether German or English, has lost the vocabulary for these sensitivities, such as the feelings of joy that descended on Klopstock on this journey:

I would really like to ponder just how far one should submerge oneself in an old poet – 'should', that is, because you can do that at will, when it doesn't matter if you resurface empty handed, unchanged, unalienated from the dive. The only thing is, that you would have nothing to say to anyone: because that is indeed just the point, that every attempt to share Klopstock with someone else ends, in that you don't trust yourself to read further, that you are almost embarrassed (with others and thus with yourself, if you are not alone) to experience feelings for which there are hardly any words more in our language.

Ich würde jetzt gern eine kleine Grübelei darüber anstellen, wie weit man sich eigentlich in einen alten Dichter versenken darf – darf, wohlgemerkt, denn können kann man’s nach Belieben, wenn es einem nichts ausmacht, mit leeren Händen wieder aufzutauchen, unverändert, unentfremdet hervor aus dem Versenken kommend. Allein mitzuteilen hätte man keinem etwas: Denn gerade das ist es ja, dass jeder Versuch, Klopstock mit jemandem zu teilen, damit endet, dass man sich nicht traut, weiterzulesen, dass man sich beinahe geniert (vor dem andern und damit vor sich, wenn man eben nicht allein ist), Gefühle mitempfinden zu können, für die es kaum mehr Wörter mehr gibt in unserer Sprache.

Rolf Vollmann, 'O silberner Mond!' in Die Zeit, 13 March 2003.

Even when we have ironed the sheet flat, when we have reached the understanding that is praeclara, how can we talk about it to anyone? Sometimes, emojis are not enough.

Notes

- The text used here is that of the 1771 edition. The poem was written and published in Zurich in 1750 under the title Zweyte Ode von der Fahrt auf der Zürcher-See. Twenty years later Klopstock made some small, mostly insignificant and mostly metrical changes. This version was published by Bode in Hamburg in 1771 under the title Der Zürchersee.

- The images copyrighted to Figures of Speech can we reused, but must be associated with a link to this page.

Update 25.07.2020

Your author is grateful to Christian Polzin for pointing out a translation error. The line Ist des Schweisses der Edlen werth! was erroneously translated as 'Is worth the sweat of the noble person!'. But der Edlen is a genitive plural, so the translation has been changed to 'Is worth the sweat of the noble ones!'.

As we all know, Murphy's Law has universal validity with no known exceptions. Thus of all the phrases to mistranslate, we chose one that occurs twice in the poem.

Update 22.10.2020

Lars Bardram made some interesting and helpful contributions in the comments.

He quite rightly pointed out that beseelt was a not uncommon word at the time; beseelteren, however, is an instance of the 'Klopstock comparative', which is indeed a Klopstock speciality.

He also pointed out that Klopstock may have been using beseelt in its alternative sense of 'lively', which in the context makes much more sense than your author's guesswork. The translation and comment in our text have been modified to reflect this. [Our original understanding of beseelt was in its sense of 'possessing a soul', which is the sense in which Goethe used it in his Römische Elegien.]

Lars was also brave enough to gloss Klopstock's puzzling Strophe 13, 14, 15 into normal German:

(Der Dichter kann) durch die Gewalt der Lieder […] ihr sanfteres ( = bildsames) Herz bilden (d.h. in dem Herzen der Ururenkel das gestalten, was die Phantasie und die Gedanken dem Dichter zugeführt haben), und dich = Liebe [die Liebe wird angesprochen], (und) dich = fromme Tugend in das bildsame Herz gießen, das ist - Goldhäufer (er/sie wird/werden angesprochen)! - nicht wenig!

Paraphrasing this in turn into English we get:

(The poet can) through the power of poetry […] form their malleable hearts (i.e. create in the hearts of the great-great-grandchildren those things which imagination and thoughts have given to the poet), and pour you = Love [Love is being addressed here], (and) you = pious virtue into the receptive heart, that is - Goldhäufer (he/they is/are being addressed)! - not little!

I am grateful to Lars for this reading, which I think is a good aid to understanding this strophe and a great improvement on my original. I have modified my translation and comments accordingly.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!