13 December: Saint Lucy's Day

Richard Law, UTC 2018-12-09 08:04 Updated on UTC 2018-12-17

In December 1798, in the small German town of Goslar, William and Dorothy Wordsworth wrote a letter to their friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was then in Ratzeburg, Germany (about 300 km away).

The exact date of the letter is not fully resolved. In it, Dorothy writes that

It is Friday evening. This letter cannot go till tomorrow. I wonder when it will reach you. One of yours was Eleven days upon the road – you will write by the first post –.

'Friday' must therefore be 14 or 21 December in 1798. Our subtitle (13 December) is therefore not quite correct – but near enough for the broadbrush standards of this website.

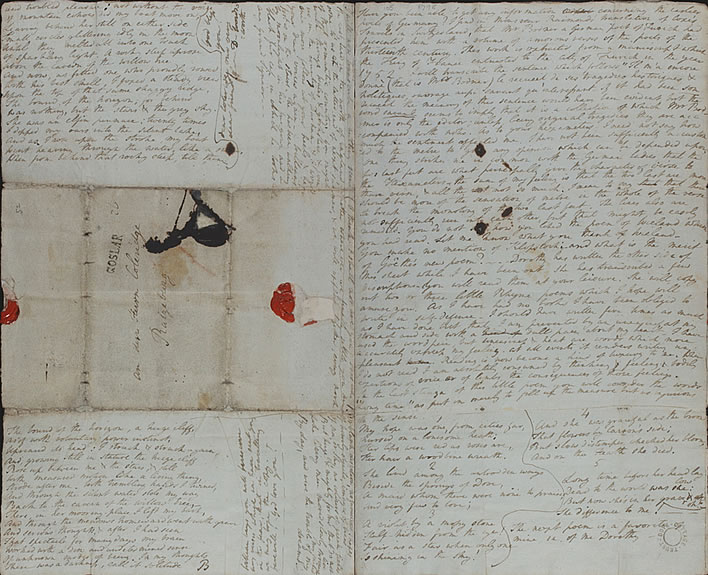

The physical form of the letter may be interesting for moderns. It was written on only one, relatively large sheet of paper, British Imperial 'uncut foolscap', 13¼ x 16½ inches (33.6 x 41.9 cm). Older British readers should note that this is not the 'foolscap' that they wrote on at school. That was 'cut foolscap', 8 x 13 inches, which was 'uncut foolscap' halved and trimmed.

The paper was folded in half crossways (8¼ x 13¼) and then folded twice to make it into a letter of (8¼ x 4¼). The total of six panels on each side were written on differently – sometimes the text flowed over several panels, sometimes it was confined to one panel. The bottom middle panel carried the delightfully simple name and address of the recipient of the letter: GOSLAR / An den Herrn Coleridge / Ratzeburg. That's what you call a postal service – who says the world has progressed in 220 years?

For dispatch the folded sheet was folded again twice so that the front displayed the address and the back was plain. The fold was held together at the back by a sealing wax seal. Paper was expensive, handmade envelopes a luxury and the Wordsworths were very strapped for cash.

You've read the thousand words – now here are the pictures that would have saved you the bother:

Dorothy and William Wordsworth's letter from Goslar to Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Ratzeburg, 14 or 21 December 1789. These images are the best we can do using pieces of images from long defunct websites. The original of the letter is in the possession of the Wordsworth Trust, which will allow visitors to Dove Cottage in Grasmere to see it only after they have paid £8.95. The Trust is proud of its outreach efforts.

Amidst the chit-chat in the letter there were some of Wordsworth's recent poems – and amidst them were two of what became known as the 'Lucy' poems. They were early drafts that went through major revisions. Readers will be delighted to hear that we are not going to produce a variorum edition of them: we are going to take their text from the published 1802 edition of the Lyrical Ballads.

There are thought to be five poems altogether in the collection known as the 'Lucy poems', but this quantity and the sequence of poems have been debated by scholars for more than a century. We are going to follow a conservative path and concentrate on the two poems that were sent in that letter from Goslar as well as the third poem that was sent to Coleridge shortly thereafter. There cannot be the slightest doubt that at least these three poems form a unity.

So, for Saint Lucy's Day 2018, 220 years after this letter was posted, let's take a closer look at this remarkable sequence of 'Lucy' poems.

Three Lucy poems

Strange fits of passion I have known,

Strange fits of passion I have known,

And I will dare to tell,

But in the lover's ear alone,

What once to me befel.

When she I lov'd, was strong and gay

And like a rose in June,

I to her cottage bent my way,

Beneath the evening moon.

Upon the moon I fix'd my eye,

All over the wide lea;

My horse trudg'd on, and we drew nigh

Those paths so dear to me.

And now we reach'd the orchard plot,

And, as we climb'd the hill,

Towards the roof of Lucy's cot

The moon descended still.

In one of those sweet dreams I slept,

Kind Nature's gentlest boon!

And, all the while, my eyes I kept

On the descending moon.

My horse mov'd on; hoof after hoof

He rais'd and never stopp'd:

When down behind the cottage roof

At once the planet dropp'd.

What fond and wayward thoughts will slide

Into a Lover's head—

"O mercy!" to myself I cried,

"If Lucy should be dead!"

This poem needs no explanation at all – in itself a testament to the plainness and clarity of Wordsworth's diction. Nor does it require great interpretative skills to tease out the metaphor of the setting of the moon and the plodding of the horse; nor great imagination to be carried away by the simplicity of the rendering of the locality.

But the suppression of all extraneous detail magnifies the intensity of the sparse, taut narrative that is there. Once read, this poem will not be forgotten quickly – if ever.

Although the poem is clear, it is not lacking in mystery. The narrator, unnerved by the augury of the moon setting over Lucy's cottage, suddenly has a premonition of his love's death, or – more accurately – a sudden understanding of how much she means to him and how much he would lose were she not there. At the time of the premonition she was, we are told, 'strong and gay' and the narrator dismisses the premonition as 'fond and wayward thoughts'. In the next poem of the sequence we find that she has indeed died.

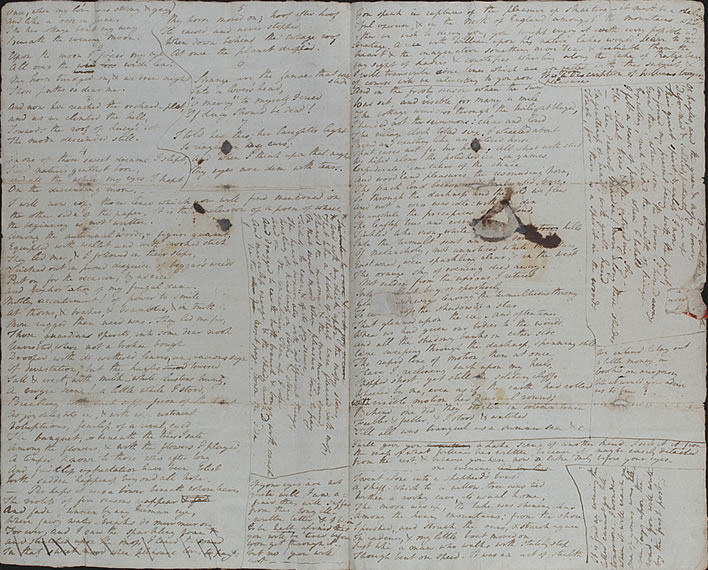

The image shows the poem as it appeared in that December letter.

As already announced, we are not going to produce a variorum edition of the text, but Wordsworth made an important change for the published text which sharp-eyed enthusiasts are bound to notice. In addition to some minor tinkering, he removed the final stanza and added what we now have as the opening stanza. That original final stanza ran:

I told her this; her laughter light

Is ringing in my ears;

And when I think upon that night

My eyes are dim with tears.

It takes little effort to work out that, once the subsequent 'Lucy' poems had been composed, this final stanza was surplus to requirements. Wordsworth, once again demonstrating the spareness of his writing, free of all excess, excised that stanza pitilessly. The new first stanza does its job and introduces that 'strange fit of passion'.

She dwelt among th' untrodden ways ['Song']

She dwelt among th' untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love.

A Violet by a mossy stone

Half-hidden from the Eye!

—Fair, as a star when only one

Is shining in the sky!

She liv'd unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceas'd to be;

But she is in her Grave, and Oh!

The difference to me.

Wordsworth's imagery is dense with information and obeys a deep internal logic. It is never mere scene painting. Lucy lives 'Beside the springs of Dove', that is, high up, where the 'untrodden ways' are, above the more populated lower valley. Even the 'mossy stone' is not simply picturesque detail but reinforces the fact that no one passes here to disturb that moss.

Wordsworth's metaphor for Lucy's existence – the beauty of the unassuming violet nestled by its stone unnoticed – once heard will stay with you. Even the superficially odd phrase 'When Lucy ceas'd to be', seemingly devoid of all emotion, is pitch perfect for the context.

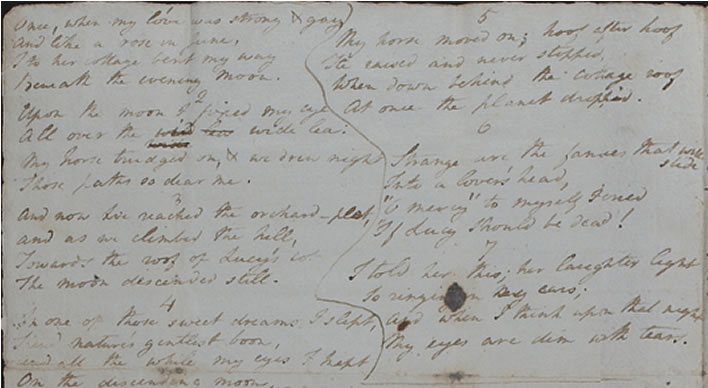

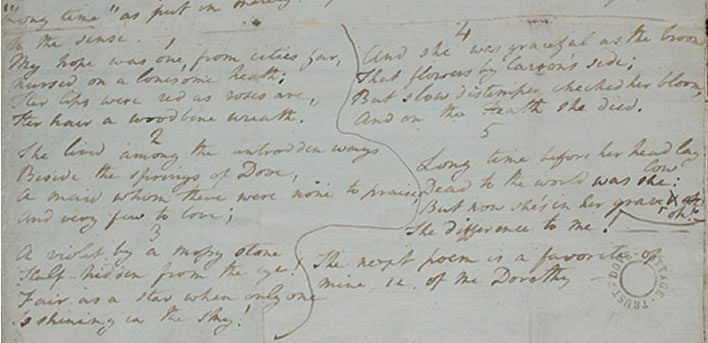

Wordsworth was even more brutal with this poem than he was with 'Strange fits of passion'. From the five stanzas of the original version he cut out two, raising the quality of the poem from good to sensationally good. The two stanzas he removed were the sort of inferior stuff any poet of the time could knock off without thinking:

My hope was one, from cities far,

Nursed on a lonesome heath;

Her lips were red as roses are,

Her hair a woodbine wreath.

No… 'lonesome heath', 'lips were red as roses', 'hair a woodbine wreath' – away with them.

And she was graceful as the broom

That flowers by Carron's side;

But slow distemper checked her bloom,

And on the Heath she died.

Away, too, with 'graceful as the broom', 'slow distemper checked her bloom', 'on the Heath she died'.

The first two lines of the final stanza, 'Long time before her head lay low / Dead to the world was she', were also rewritten and greatly improved: 'She liv'd unknown, and few could know / When Lucy ceas'd to be'. It is a privilege to be able to observe a great poet's mind at work in this way.

The attentive reader will have also noticed that these new lines opening the last stanza now mention Lucy explicitly, thus tying her to what has gone before and clearly identifying the 'Lucy' sequence.

A slumber did my spirit steal

A slumber did my spirit steal,

I had no human fears:

She seem'd a thing that could not feel

The touch of earthly years.

No motion has she now, no force

She neither hears nor sees

Roll'd round in earth's diurnal course

With rocks and stones and trees!

After the description of Lucy's importance for the narrator and his love for her, the reader is stunned by the third poem.

All the conventional platitudes of an afterlife in heaven and a hoped for reunion are brutally smashed: 'She neither hears nor sees'. How different this is from the touching belief in the resurrection and reunion of lovers we met in our contribution to last year's Lucy's Day, Johann Peter Hebel's (1760-1826) classic German story Unverhofftes Wiedersehen from 1811.

In contrast, Wordsworth's Lucy at her death became part of the overarching order of Nature – and not just the bucolic Nature of wood, field and lake, but the great cosmic clockwork itself. What remains of her has joined the cosmic order of being, as we are told in one of the most arresting images in the whole of poetry in English: 'Roll'd round in earth's diurnal course / With rocks and stones and trees!' Great poetry: once read, never forgotten.

Lucy is not mentioned by name at all in this poem, a fact which some have taken to be a weakness of the construction of the sequence. It is not. It is, in fact, a great strength, because, as Wordsworth told us at the end of the previous poem, she has 'ceas'd to be'. Lucy is no more: she 'seem'd a thing' that is as inanimate as 'rocks and stones and trees', now without motion, force, hearing or sight. Lucy is no more and her name has gone just as she has.

On reflection, we realise that the sudden Copernican viewpoint of the rotation of the earth in its 'diurnal course', so startling, so novel, was, in fact prefigured in the first poem of the three, when we watched 'the descending moon', 'the planet' traverse the Ptolemaic heavens. So much astronomy in only two poems – who says they are not a unity?

All the three 'Lucy' poems give us Wordsworth at his magnificent best. The reader does not stumble over clever artifice, scratch a head and reach for commentaries. The metre and rhyme scheme are so ordinary – a poetic workhorse – that they are often called 'common measure'. The reader is carried onwards by the force of the original thoughts and perceptions from an original mind to pay that greatest compliment for the poet: 'I'm glad I read that.'

As already mentioned, Lucy is not mentioned by name in the third poem, but in the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads the three poems are printed together. There are so many similarities of context and technique within the three poems that is would be perverse to exclude A slumber did my spirit steal from the Lucy poems.

Who was Lucy?

Much scholarly fantasy and dedicated scribbling has been invested in the hunt for Lucy. It is a fatuous pastime, this Find-the-Lady game that critics find so addictive. If Wordsworth had wanted to identify her with a real person he would have done so. There is no hint in any of his writings or letters about a Lucy, who lived '[b]eside the springs of Dove'.

Even if Lucy represents an existing person and even if we knew who that person was, that knowledge would add nothing to the poems – they are complete and need no external references.

In fact it would detract from the poems. A moment's reflection will tell us that finding an historical Lucy is the last thing we should be trying to do, for it would wreck the meaning of the sequence completely. Lucy lived unknown to the wider world – why should we expect to know of her, two centuries later? She 'ceas'd to be' – how can we now resurrect her?

The most bizarre suggestion in the hunt for Lucy is that she is a representation of Dorothy Wordsworth herself. Bizarre, because there is not the slightest alignment in their two biographies. The suggestion is used as a lever to recycle the theory of an incestuous relationship between the siblings, for which there is no evidence either.

Returning to rationality for a moment, there is the tiniest possibility that Wordsworth's inspiration for the name – though not the character – came from the impending Lucy's Day.

But not only does he make no mention of this inspiration, the festival itself at that time was a strictly Scandinavian affair – it appears to have gone more or less unobserved in Germany. Both he and Coleridge remark on the very Germanic observance of Saint Michael's Day and Saint Nicholas' Day, but of Lucy's Day there is no mention. Even if, by some tenuous connection, the use of the name Lucy was not completely coincidental, there is not the slightest trace of the early Christian martyr Lucy, her legend or her observance in the 'Lucy' poems.

Apart from the fact that the poems do not tell of snow on the fells, they are completely free of seasonal allusions, so that the date of Lucy's Day as the former winter solstice has no relevance for the poems at all. Saint Lucy might just possibly have given her name, but nothing else. Finally, given the underlying atheism of the poems, an association with a Christian martyr would be completely out of place. So, bang goes another nice theory.

The German jaunt

The reason why we have one Lake Poet and his sister in Goslar and another 400 km away in Ratzeburg on what was supposed to be a joint cultural visit to Germany requires some explanation. As with all matters involving Coleridge the tale is by turns entertaining and repellent, but frequently devoid of inner logic.

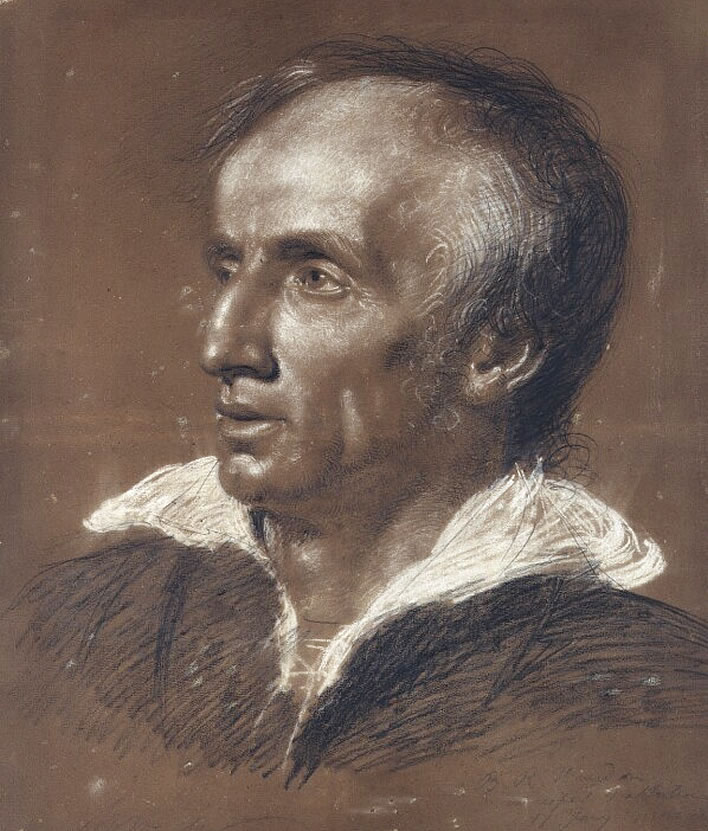

Samuel Taylor Coleridge by Peter Vandyke (1729-1799), oil on canvas, 1795. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Up until June of 1798, Coleridge (1772-1834) and his wife Sara (née Fricker, 1770-1845) and Wordsworth (1770-1850) and his sister Dorothy (1771-1855) had been part of a literary menage based on Alfoxden Hall (now usually 'Alfoxton') in Somerset, only a short distance from the Bristol Channel. In that month their lease was terminated, presumably because of the Jacobin reputation the group had gained, a dangerous thing in those tense times. Making a positive out of a negative – a Coleridge speciality – this was the impetus that gave Coleridge the idea to travel to Germany.

Readers who want a quick summary of Coleridge's character and decision-making processes should think of a slightly wilder version of Mr Toad in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows (1908).

Wordsworth and Coleridge in Germany, September 1798 - June 1799. Image: Base, Google Maps; layer, FoS.

Germany was one of the places to go for the travelling English of the time. France was the enemy, still in turmoil and still fighting wars. In 1800, its allies deserted or defeated, Britain was left to fight Napoleon Bonaparte on its own. For intellectuals such as Coleridge, Germany was the philosophical and cultural magnet of the time.

The University of Göttingen, for which Coleridge was ultimately headed, had been founded in 1734 by George II, King of Great Britain and Elector of Hanover. We mentioned the foundation of the University in our recent piece on Albrecht Haller, who did as much as anyone to build its reputation.

At the time of Wordsworth and Coleridge's tour, George III was on the throne, a reign notoriously eventful and plagued with mental illness. If nations can be considered to be brothers, Germany and Britain were such. Despite its political fragmentation, Germany had taken the cultural and intellectual lead from France, German writers were now the recognised masters of the 'Sublime'. At that moment, in Coleridge's eyes, Germany was where it was at.

The small matter of paying for this adventure gave Mr Toad no sleepless nights. He managed to enthuse his sponsors, the Wedgwoods, to finance his Bildungsreise. Coleridge had originally planned to take his wife Sara and his children, but this would have overstretched his budget. Wordsworth did not seem to realise that he was in exactly the same position: it would turn out that the company of Dorothy was a luxury he could not afford.

To Germany it was, then, and the Wordsworths would come too and they would all learn German together and experience the cultural vortex of Germany. After some nomadic weeks, Coleridge, a young farmer called John Chester, whom Coleridge used as a recipient of his erudite monologues and who was to study German agricultural techniques, and the Wordsworths embarked on the packet from Yarmouth to Cuxhaven on 16 September 1798.

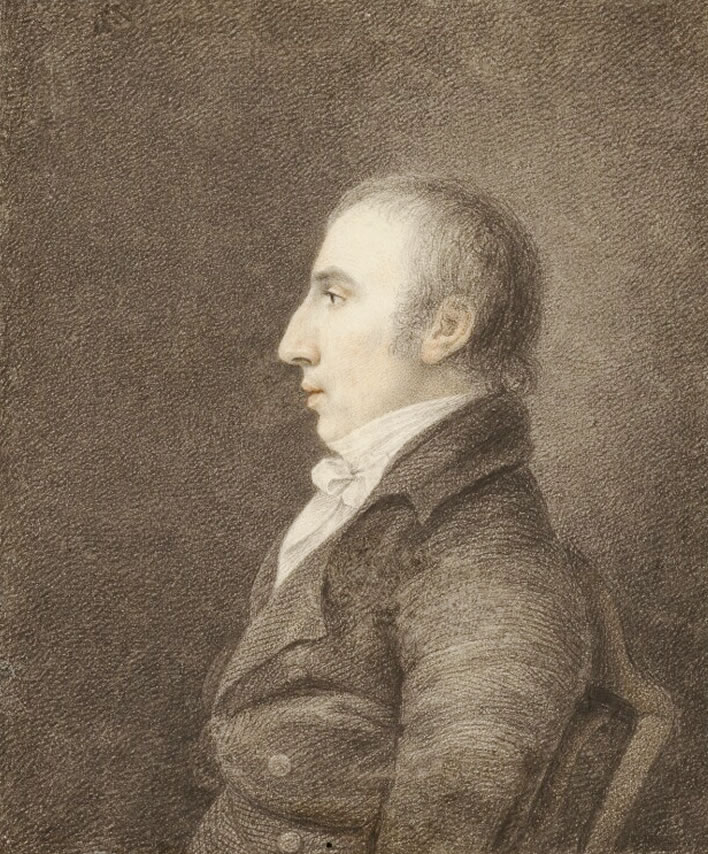

The earliest known portrait of William Wordsworth, painted by William Shuter in 1798. Wordsworth was 28. Image: The Cornell Wordsworth Collection.

For the Wordsworths, the disaster of this tour began shortly after departure. A lively sea laid them both low with seasickness. Foolishly, they went below, loosing sight of the horizon and for the two day duration of the crossing were racked with violent sickness. Meanwhile, Coleridge strode around the deck unaffected, socialising vigorously with the other passengers, a captive audience. That crossing would become a metaphor for their very differing fortunes during the entire project. At last they reached Cuxhaven, then sailed the hundred or so kilometres up the Elbe to Hamburg, arriving there on 19 September.

The parting of the ways

By the end of September, after two weeks in Hamburg, they split up. Coleridge and Chester left to overwinter in Ratzeburg, which they had already reconnoitred as an agreeable place to spend a couple of convivial months in the depths of a very cold winter. The fraternal feelings that existed at that time between the British and the Germans could not be better illustrated than by the warmth of Coleridge's acceptance into the society of Ratzeburg. Wordsworth and Dorothy left for Goslar, a small town in the Harz Mountains.

All the fault lines in the Coleridge-Wordsworth travel undertaking shifted simultaneously. The dominant one of these was money: Wordsworth and his sister cost twice as much as Coleridge (Chester seems to have been self-financing). More important than the absolute cost was the perception of value. Wordsworth found the prices in Germany exorbitant – a feeling every continental traveller on a budget confronted with the horrors of currency conversion knows only too well.

Whereas the cast of mind of the gregarious and convivial Coleridge would allow him to float around in the agreeable society of Ratzeburg, Wordsworth's financial worries forced him to retreat into his shell and 'seek, lower down, obscurer and cheaper Lodgings without boarding', as Colderidge put it. This decision in turn opened up other fault lines and contradictions.

William Wordsworth, by Robert Hancock (1730-1817), black, red and brown chalk and pencil, 1798. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

The Wordsworths: down and out in Goslar

Wordsworth, in the middle of an extremely productive period that had started in Alfoxden, now just wanted peace and quiet to pursue his poetry – which causes us to ask: why go all the expensive way to Germany in order to live as a recluse? Coleridge complained: 'he might as well have been in England as at Goslar, in the situation which he chose, and with his unseeking manners'. The Lucy poems we reproduced here are one small sign of that productivity.

Another fault line: Wordsworth was supposed to be learning German. He made some efforts, but his mind was submerged in his English poetry. Coleridge, in contrast, took the total immersion technique of language learning to its logical conclusion and spent much of his time learning, reading speaking and writing German. He was rather disgusted at Wordsworth's defection to English.

One more fault line: what does one make, socially, of a brother and sister travelling and living together? Coleridge again, wise after the fact, as ever: 'His taking his Sister with him was a wrong Step - it is next to impossible for any but married women […] to be introduced to any company in Germany. Sister is considered as only a name for Mistress.'

In the context of our recent piece about the modern misunderstanding of the historical attitude to homosexuality, we note here that Coleridge and young Chester as travelling companions never raised an eyebrow, whereas brother and sister was a cause for some suspicion.

We thus find Wordsworth and Dorothy living in a barely-heated attic room in Goslar in the coldest winter in living memory, eking out their money on scarce rations and living in a bubble of social isolation. Dorothy herself pointed out to a correspondent that they could not accept social invitations simply because they could never return them.

To all this misery we must add the rift of the worst and most painful fault line: the absence of Coleridge. Wordsworth was torn between his two loves. He had his sister and that relationship of love and irritation that would last his entire life; but Coleridge, the sparkly meteoric Mr Toad, who did so much to cheer up Wordsworth, the natural depressive, was a long way away talking, dancing, eating and drinking the cold away with his new friends in Ratzeburg (and later in Göttingen).

Richard Matlak wrote a much cited paper on the social dynamic between Wordsworth, Dorothy and Coleridge during their time in Germany. Although there is much wild psychobabble in his paper, he did point out credibly the mental tortures that Wordsworth must have been experiencing, among them the guilt and gnawing annoyance he must have felt that, if it were not for his sister's expensive presence, he, too, could have been with Coleridge enjoying the social delights Germany.

We know, of course, that he would have hated that life within half an hour and hated himself for participating in it – the loss of his solitary creative space, the loss of time to think and write.

We poetry-reading posterity are selfishly glad of Wordsworth's decision to endure the cold, hunger and all the other privations to which he and Dorothy were subjected in Goslar: he left us the 'Lucy' poems, the 'Matthew' poems, Lucy Grey, most of part 1 of The Prelude including related poems such as Nutting and There was a boy etc. The alternative would have been a much smaller output, but a poet who understood German quite well.

Coleridge: carousing in Göttingen

Coleridge and Chester left Ratzeburg for Göttingen on 6 February 1799. There the social whirl whirled even faster, Coleridge reverted to being an undergraduate, visited lectures and engaged in pointless philosophical debates. He began a mammoth project, translating some of Lessing into English or writing his biography. His time at Göttingen was extended and extended.

His wife Sara, braced for an initial three-month absence, had already missed him for several months in Britain before he set off. As time dragged on her initial helpless toleration turned into great bitterness. In all, Coleridge spent ten months in Germany, drastically overspending his future allowance.

Coleridge's stay in Germany had been planned as a three-month tour, but lasted for ten. He wrote frequently and delightfully to Sara during this time, but communications were often disrupted by the severity of the weather. In December he finally learned that his infant son Berkeley had been seriously ill.

Sara's letters to him were carefully phrased to avoid disturbing the great man's mind – or not written or sent at all. His old friend Thomas Poole (1765-1837), in whose house Sara was living during Coleridge's absence, acted as the gatekeeper of his sensitive psyche.

Coleridge never knew, for example, how much Sara had suffered during Berkeley's illness, the result of a smallpox inoculation gone wrong. The attack badly disfigured the infant and left him terminally weakened. After that, it was only a matter of time for the boy: on 11 February, whilst in Germany Coleridge's coach was coming in sight of Göttingen, in Nether Stowey, Somerset, Berkeley died in a convulsive fit.

Sara, already in a terrible state, broke down almost completely. Poole's mentoring, dutiful kindness had run its course. She left his house and was taken in by the Southeys (the poet Robert Southey had married Sara's sister Edith in 1795). In late March Sara, now free to write to her husband at will, wrote Coleridge a letter of the deepest agony.

When Coleridge in Göttingen learned of his son's death on 4 April in an emotionally sanitised letter from Poole, the great writer of mesmeric English found no words to deal with his loss – he replied with a brief and embarrassingly scholastic dissertation on philosophy.

For the emotional component of that reply Coleridge sent his friend a proxy: a copy of Wordsworth's 'Lucy' poem A Slumber did my spirit steal, one of those poems that Wordsworth had written in that freezing garret in Goslar – an unmatchable expression of loss. With that our circle around the 'Lucy' poems closes.

Sara's letter of spiritual agony was answered with a further philosophical disquisition, accompanied by an epitaph that Coleridge had written a few weeks before on the death of someone else's child. In the middle of all this grief he announced his intention to stay on at Göttingen to finish his studies and the great work on Lessing.

There is no doubt that Sara was treated very badly by Coleridge – marry the pretty, lively girl in haste; repent and come to despise her at leisure. This is not the place or time to try to disentangle that mess, but we should note that she has been generally treated with an almost equal disdain by literary biographers down the years. If, Reader, before coming to this piece, you knew her first name, her maiden name or her birth and death years, you may reward yourself with another biscuit and count yourself among the very few that do.

Parting, returns and reunions

In mid-April 1799, Wordsworth and Dorothy visited Coleridge in Göttingen. They had parted at the end of September 1798 and managed to meet up again a little over six months later. We sometimes read that the Wordsworths chose Goslar for its relative proximity to Göttingen (c. 70 km), but this proximity proved wasted in practice. Finally face to face, they tried to persuade him to return to Britain with them. He refused. They left, convinced that the great friendship with Coleridge was now in decline, and returned to Britain, finding some accommodation with their friends the Hutchinsons in Stockton on Tees in the north east of England.

Coleridge and Chester finally left Göttingen on 24 June 1799 and took a good month to wend their leisurely way back to Britain. It would be the middle of September before Coleridge wrote to Wordsworth again and the end of October before they would meet again. The great literary partnership had somehow survived the juddering of the fault lines that had taken place during the German adventure.

The shared life in the Lake District that would briefly heal many of the ruptures was yet to come. It started on 29 June 1800 when Coleridge and Sara arrived at Wordsworth's rented residence, Greta Hall in Grasmere. But it would also, within six months lead to even greater shifting of the tectonic plates.

William Wordsworth by Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786-1846), chalk, 1818. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Update 17.12.2018

The cold winter of 1798

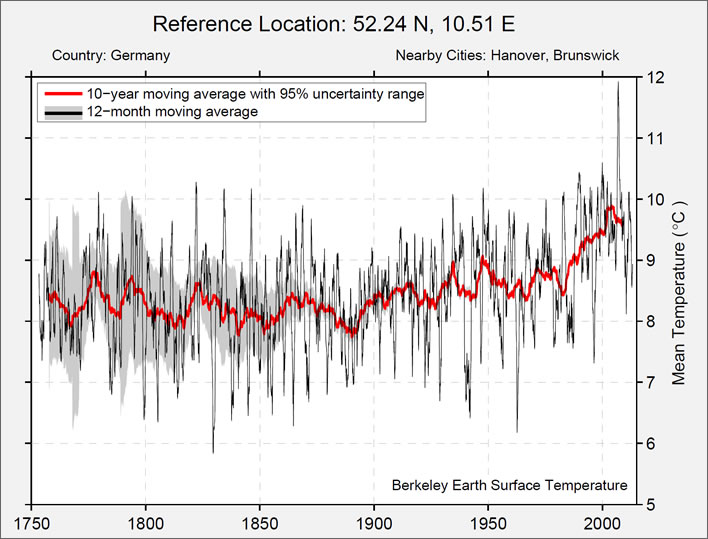

According to the Berkeley Earth temperature data for the location around Göttingen (i.e.: Hanover, Brunswick, Magdeburg, Göttingen, Wolfsburg, Salzgitter – which also includes Goslar), the winter of 1798, when the Wordsworths and Coleridge were in Germany, was, indeed, an exceptionally cold winter. It can clearly be seen on the temperature chart for 1750-2013:

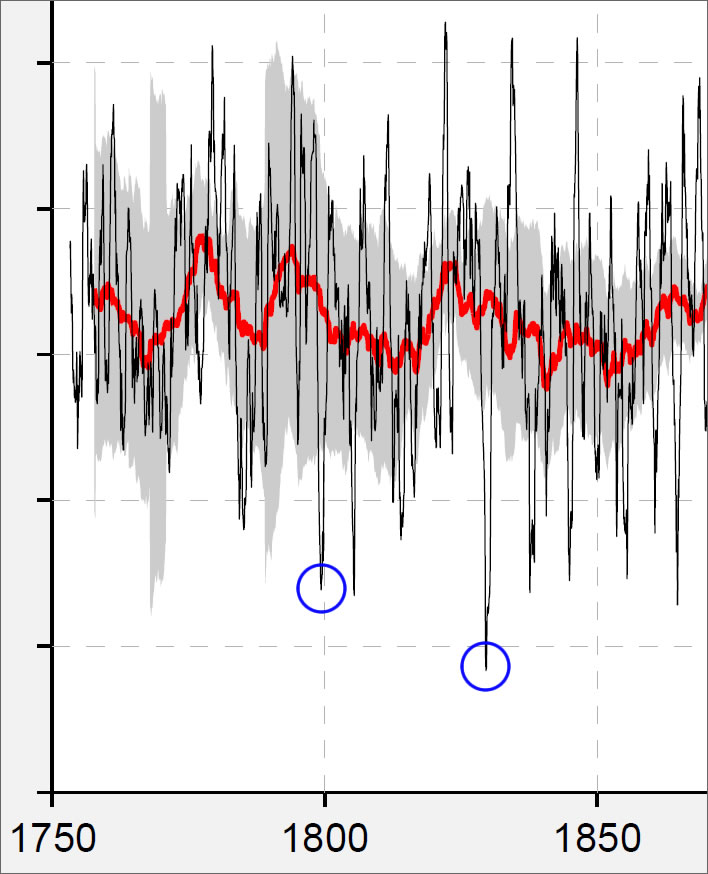

Here is a closer view with the low temperatures for the winter of 1798-99 circled. The all-time coldest winters in the region according to Berkeley Earth occurred between 1828 and 1830.

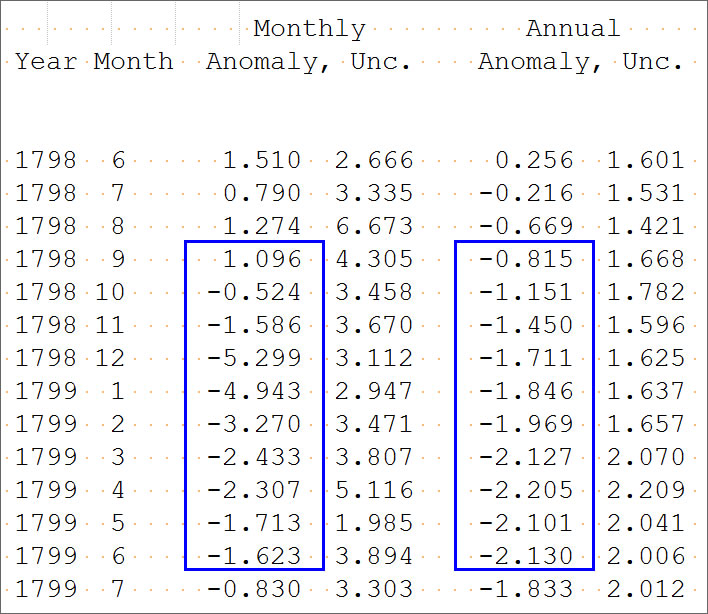

For those with numerical minds here are the temperature anomalies (month and year) for 1798-99. Our travellers arrived in September 1798 and left in April (Wordsworths) and June (Coleridge) 1799.

Berkeley Earth temperature data normally has to be taken with several pinches of salt, since their algorithms do a lot of infilling and 'improvement' work on erratic data. In this case, their results complement anecdotal evidence, since the cold spell would definitely have been a phenomenon across central Europe. Both the Wordsworths (in Goslar) and Coleridge (in Ratzeburg, then Göttingen) would have experienced similar low temperatures.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!