Jägers Liebeslied D 909

Posted by Richard on UTC 2020-01-24 09:03

Introduction

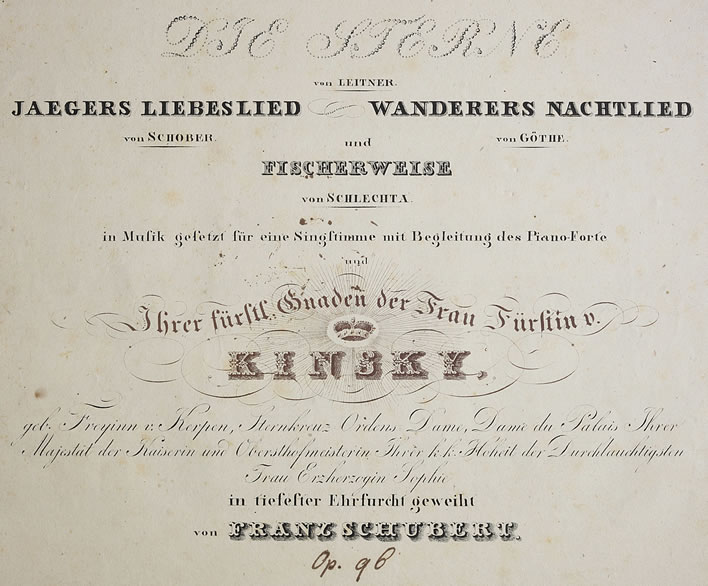

In our piece on the Kinsky concert given by Schubert and Schönstein around the beginning of July 1828 we noted the dedication of an album of four poems as Opus 96 to Princess Charlotte.

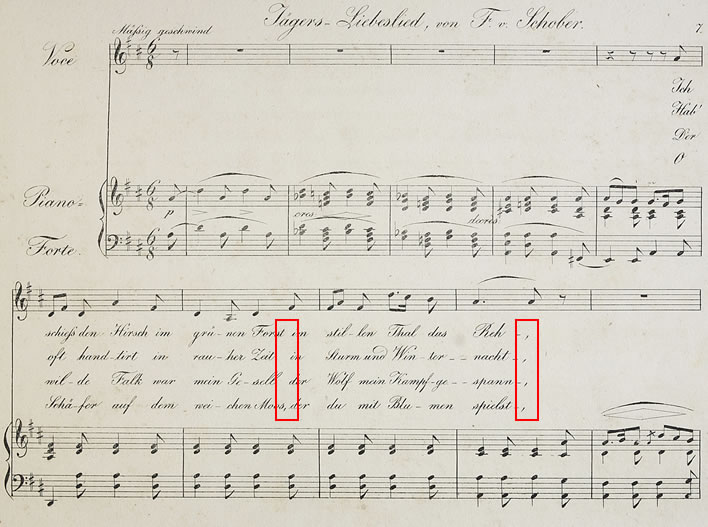

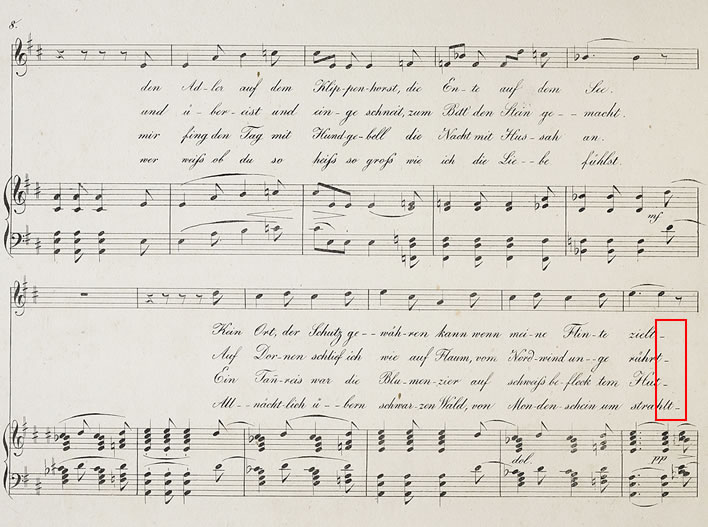

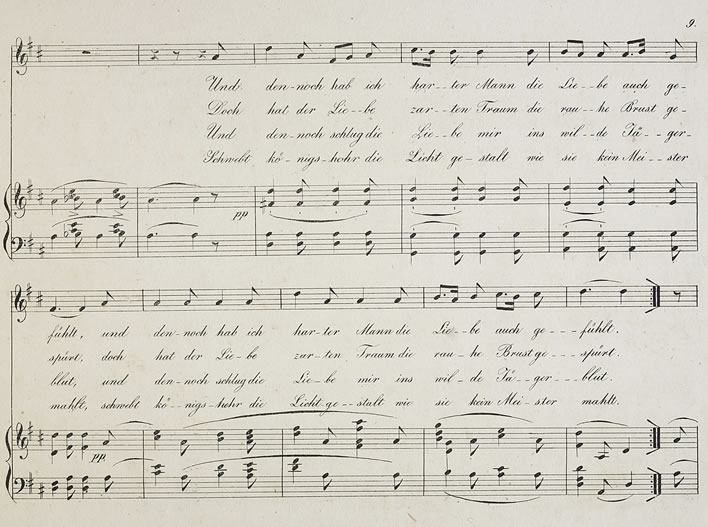

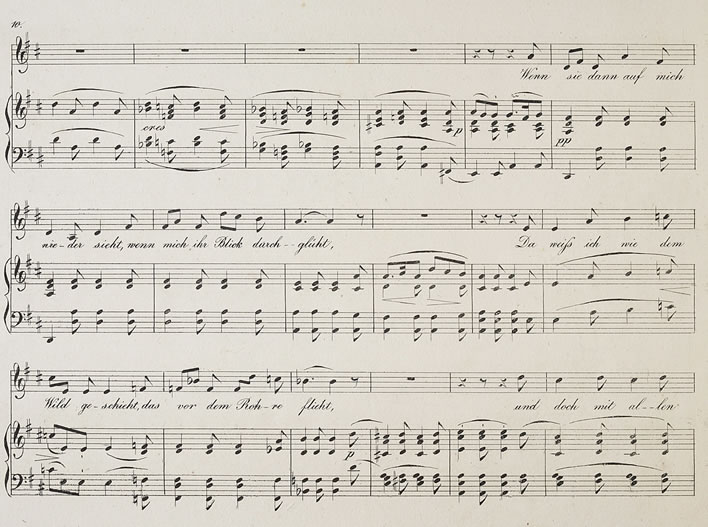

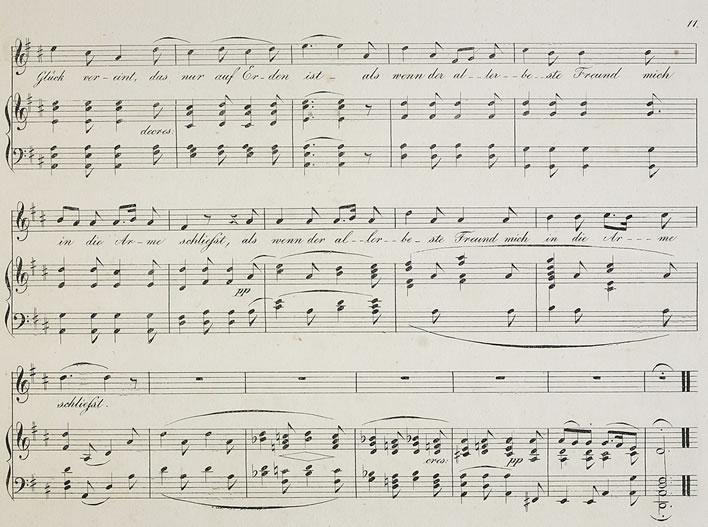

The cover page of the printed album for Opus 96 (1828), dedicated to Charlotte Princess Kinsky. Image: Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Online. All the images of musical scores used in the rest of this article come from this source.

The four poems are Die Sterne (D 939, 1828), Jägers Liebeslied (D 909, 1827), Wandrers Nachtlied (D 768, 1824) and Fischerweise (D 881, 1826), in this order.

Of these four songs, so far we have looked at Wandrers Nachtlied, which we considered to be a true diamond: a brilliant text in a brilliant setting. We have also looked at Fischerweise, a happy accident of a text which Schubert's setting managed to turn into cut glass, at least. Then came that grubby juvenile stone Die Sterne.

After that last dismal encounter the only task left is to take on Jägers Liebeslied, written (date unknown) by Franz von Schober (1796-1882) and composed in February 1827.

Jägers Liebeslied , Schober's poem

Our introductory remarks to Fischerweise could well be repeated here. The executive summary: if you wanted to write prose, drama or poetry under the belljar of the Austrian Empire, its subject and viewpoint had better be inconsequential or it would never be published.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Franz von Schober, 1821.

Schober's poem Jägers Liebeslied is yet another good example of that fact. Its content is definitely inconsequential, or it was in Schubert's day. In our woke times, however, all this hunting and killing animals would definitely be unacceptable.

In this poem, a hunter has fallen in love. Forty longish lines are required to deal with this earthshaker, forty lines of rustic Nature. The dramatis personae of the poem contain an extensive assembly of those trusty spear carriers of Romantic poetry: stags, deer, eagles, ducks, winter, shepherds, flowers, moss, moonlight etc. The conceit in the poem, repeated in each of the first four stanzas, is that the hard, rough hunter has been smitten by love, just as badly as he smites his own prey.

Here is Jägers Liebeslied in the form in which it appears in Schober's Gedichte von Franz von Schober from 1842. Schubert made some changes, which are highlighted in yellow. Hover the cursor over the highlight to see a tooltip with Schubert's change.

|

Jägers Liebeslied

Ich schieß' den Hirsch im dunklen Forst, Im stillen Thal das Reh, Den Adler in dem Klippenhorst, Die Ente auf dem See. Kein Ort, der Schutz gewähren kann, Wenn meine Flinte zielt; Und dennoch hab' ich harter Mann Die Liebe auch gefühlt! – |

The Hunter's Lovesong

I shoot the stag in the dark forest, the deer in the silent valley, the eagle in the cliff nest, the duck on the lake. [There is] no place that can give protection when my gun takes aim; And yet have I, hard man, also felt Love! |

| Hab oft hantirt in rauher Zeit, In Sturm und Winternacht, Und übereist und eingeschneit Zum Bett den Stein gemacht. Auf Dornen schlief ich wie auf Flaum, Vom Nordwind ungerührt, Doch hat der Liebe zarten Traum Die rauhe Brust gespürt. |

Have often worked in bad weather, in storm and winter night, and covered with ice and snowed in made my bed on stone. On thorns have I slept as though on down, untouched by the north wind, yet the raw breast has felt the soft dream of Love. |

| Der wilde Falk war mein Gesell, Der Wolf mein Kampfgespann; Es fing der Tag mit Hundgebell, Die Nacht mit Hussa an. Ein Tannreis war die Blumenzier Auf schweißbeflecktem Hut, Und dennoch schlug die Liebe mir Ins wilde Jägerblut. |

The wild falcon was my companion, the wolf my battle brother; the day began with barking dogs, the night with 'tally-ho'. A pine twig was the flower on my sweat-stained hat, and yet Love struck me in my wild hunter's blood. |

| O Schäfer auf dem weichen Moos, Der du mit Blüthen spielst, Wer weiß, ob du so heiß, so groß Wie ich die Liebe fühlst. Allnächtlich überm schwarzen Wald, Vom Mondenschein umstrahlt, Schwebt königsgroß die Lichtgestalt, Wie sie kein Meister malt. |

O shepherd on the soft moss, who plays there with flowers, who knows whether you feel Love as hotly and greatly as I do. Every night above the dark forest, bathed in moonlight, floats as great as a king the luminous form, as no artist can paint it. |

| Wenn sie dann auf mich niedersieht, Wenn mich der Blick durchglüht, Dann weiß ich, wie dem Wild geschieht, Das vor dem Rohre flieht. Und doch! mit allem Glück vereint Das nur auf Erden ist; Wie wenn der allerbeste Freund Mich in die Arme schließt. |

When Love then looks down on me, when Love's gaze burns through me, then I know how the prey feels as it flees the barrel. And yet! united with all the happiness that is only on earth; as when the greatest friend encloses me in his arm. |

Staying with the hunting metaphor for a moment, this poem lays an unavoidable bear trap for the translator.

The reason is that Schober never writes of the loved one as a living person: he always uses die Liebe, which can mean love in the abstract, 'Love', or a (female) person, in the sense of 'the loved one' or 'the beloved'. Since Schober mentions no characteristics of a real person and even in the penultimate verse represents this object as die Lichtgestalt, 'the luminous form', we have our problems calling this object the 'loved one'.

Having invented die Lichtgestalt (feminine gender) in stanza five, at the beginning of the following stanza he can refer to it as sie with complete grammatical correctness but with complete semantic confusion – is this a woman (feminine), Love (feminine) or the bright image (feminine)? Schober then writes of der Blick, sidestepping the problem, but Schubert corrects this, presumably to maintain consistency with sie, into ihr Blick, 'her', thus prolonging the ambiguity.

It appears that Schober, in order to avoid for whatever reason mentioning a flesh-and-blood female, is using Die Liebe in the abstract sense. For that reason your translator has consistently capitalised 'Love', since English offers us no possibility of 'the Love'.

The last verse will cause the members of the Schubert et al. were gay crowd to start hyperventilating: 'when the greatest friend (masculine) encloses me in his arm' – and that in the context of the exclusion of any particular woman in favour of some abstraction of Love. At least this stanza is more interestingly homosexual in its language than anything else the gang have discussed – that rough, butch hunter who wants nothing more than his best friend's arm around him. Brokeback Mountain, anyone?

But for every poem we have to ask: who is the narrator and where is the poet? The idea of Franz Schober as the rough, hard-as-nails hunter, the Ich-narrator, is clearly absurd – this hunter must be an adopted persona of Schober's, a projection of his mind.

A fevered imagination might see Schober here in his role as the successful hunter of young women. However the success chronicle is restricted to the first stanza – nothing else in the poem corresponds to this view, so the idea of Schober using the poem to boast about his conquests quickly rejects itself. Anyway, such metaphorical insights were beyond Schober's talents.

There is also no reason to assume that the hunter's final dream of being wrapped in his best friend's arms is anything more than the poet remaining in his adopted persona. Schober himself was not speaking in the previous four stanzas, why should he suddenly be speaking now?

The censor would have jibbed at a poem in which a woman wrapped a man in her arms outside wedlock, consequently we have no idea whether Schober's original text was different. There is no evidence for this, but the last two lines of the poem are so ill-fitting that they arouse the suspicion that they may have been simply a quick fix to bring the poem into the zone of acceptability.

The nuts and bolts of the poem are competent, the metre is maintained without incident, readers are not challenged with enjambements or caesurae. On occasions, though, the rhyming reeks of desperation: zielt-gefühlt, spielst-fühlst, durchglüht-flieht, ist-schließt. In sum, the poem is inconsequential nothingness.

Jägers Liebeslied , Schubert's setting

The description of the hard life of the hunter makes the mood of the entire poem hard. We only need to review the vocabulary to get this flavour: shoot, bad weather, storm, winter night, ice, snowed in, bed of stone, thorns, north wind, raw breast, wild falcon, wolf, battle brother, barking dogs, sweat-stained hat, wild hunter's blood – all the meaty attractions the schöne Müllerin found so irresistible, compared with the limited and floury attractions of the miller, who, like the shepherd in the present poem, reclined on moss and played with his little flower friends.

The minor tones of Schubert's opening bars seem to suggest this impending darkness to us, but after that, the gentle cantering rhythm and the sweet sing-song melody with the usual twiddles and doodles take over and detach the mood of the music from the darkness of the underlying text.

Your author has no musical ability at all, but at times he wonders whether this music was composed for this poem, so detached it seems. The words move along their grim, manly track whilst the music canters and twirls away effetely alongside them.

Apropos cantering rhythm, now and again we expect the song to turn into Alinde (D 904). We note that Alinde was composed in January and Jägers Liebeslied in February 1827. Clearly, cantering was on Schubert's mind at that time.

A few bars later more cantering trots through our memory, this time from Das Fischermädchen (D 957, composed August 1828). Before long this listener is so befuddled with all this cantering that he is even expecting a bit from The Lincolnshire Poacher to pop up: 'Oh, 'tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year'.

Schubert has taken the line pairs in Schober's text and joined them together in a musical enjambement, where no textual enjambement exists – in these places in the text there is a comma, the presence of which is demanded by sense and grammar. Despite this, it is impossible for a native German speaker to sing these 'enjambements' without some sort of pause – just not writing the comma demanded by sense and grammar doesn't work.

At one point, O Schäfer auf dem weichen Moos, Der du mit Blüthen/Blumen spielst, Schubert is forced by iron grammar to preserve the comma yet keep the melodic enjambement. Tsk, Tsk.

In effect, Schubert has taken Schober's eight line stanzas and turned them into four line stanzas:

Ich schieß' den Hirsch im grünen Forst, Im stillen Thal das Reh,

Den Adler auf dem Klippenhorst, Die Ente auf dem See.

Kein Ort, der Schutz gewähren kann, Wenn meine Flinte zielt –Und dennoch hab' ich harter Mann Die Liebe auch gefühlt!

Whether this makes more metrical and semantic sense than Schober's original is a matter of taste. In the first four stanzas Schubert has also wisely detached the final two lines that describe the hunter's subjection to 'Love' with a suspenseful intermission. To reinforce this change he has also replaced Schober's weak and indecisive punctuation of the separation with a much firmer dash – a great improvement.

The final stanza quite rightly gets its own treatment:

But in the middle of all this joyous cantering and warbling we frolic up to Schober's frightful simile:

Wenn sie dann auf mich niedersieht, Wenn mich ihr Blick durchglüht,

Da weiß ich, wie dem Wild geschieht, Das vor dem Rohre flieht,

'When Love's gaze burns through me, then I know how the prey feels as it flees the barrel', culminating in 'united with all the happiness that is only on earth'. Unfortunately, Schober's poetic incompetence allows this most dramatic statement to fizzle out in one rather odd line.

It is not a fair comparison, but, whilst searching for a meaning in Schober's trite statement, moderns may recall Hemingway's equivalence of sex and death in For Whom the Bell Tolls:

'Oh,' she said. 'I die each time. Do you not die?'

'No. Almost. But did thee feel the earth move?'

'Yes. As I died. Put thy arm around me, please.'

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), For Whom the Bell Tolls, 1940. Chapter 12. For that great writer's use of chiastic form see Hemingway under the hood.

But we shall have to wait more than a century for that thought to achieve its masterful articulation.

Your author, no musician at all, is left baffled after Schubert's melody canters into this simile – arguably one of the best lines in this poem – and then canters cheerfully out again.

Once again in this song, the music wanders away from the meaning. Is this Schober's fault for embedding a serious conceit in what is otherwise bucolic pap? What else, in the context of all this jolly rusticality, could Schubert have done?

Conclusion

Schober's poem has many defects. Some of these are trivial, the things that only poetic pedants notice, and some are major, such as the fantastical figure of a incorporeal 'Love' and the sudden surprise of its Brokeback Mountain conclusion. It would be a surprise to learn that anyone had committed even parts of this poem to heart, so trifling and inconsequential it is.

Schubert's musical setting is a pleasant listen, just as long as the listener doesn't listen to the words. There are probably biographical reasons why Schubert chose to set this poem of Schober's to music, but if there are, we do not know them and cannot begin to imagine what they were.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Franz von Schober [ND], Wienmuseum, Austria. Torup castle is in the background, taken from a sketch of Schober's.

In the last two years of Schubert's life, Schober was an appreciable presence – in ways we do not really understand. The Schober family had only shortly before the composition of this piece moved into their expansive apartment in the house Zum blauen Igel and Schubert had moved in as their guest. What rent he had to pay – if any – is unknown (to your author, at least).

Were compositions of Schober's work the Danegeld Schubert felt he had to pay? Why would Schubert insert this unsatisfactory song in the album for Charlotte Princess Kinsky? And why did Schober's rickety printing house get the job of printing it? Who really knows? Schubert spent more than a year living in the Schobers' pleasant apartment, but moved out in the summer of 1828, for reasons that are unclear.

A few months later, on his sickbed, Schubert's last letter (at least, the last we know about) was written to Schober. We know of no reply. Schober does not appear to have visited Schubert in those last weeks – it is presumed that the fearless, iron-souled hunter was too worried about catching something from Schubert and/or preoccupied with the expensive crash dive of his printing company into insolvency.

In the context of the four songs that make up the Opus 96 album, Jägers Liebeslied forms an interesting pendant to Fischerweise. They both draw on the Romantic theme of Nature, but the latter is manly, a paean to freedom and independence and a rejection of the entrapment of love in the form of the shepherdess fishing from the bridge.

In contrast, Schober's poem, despite its superficial, overstated, camp manliness, ultimately ends in the loss of freedom in its dramatic subjugation to the best friend's arm. The freedom of Schober's hunter is really an expression of a fearful masochism. Schober's dangerous shepherdess is the soft-skinned shepherd, sleeping on moss, playing with flowers, an image of an easy life that the hunter dare not take.

Your author calls to mind a shade from his youth who rejected his bed and slept in a hammock slung outside his window (seventh floor!), that he should not grow soft. Your author, after dabbling very briefly in some manly pursuits, decided that soft was the way forward.

If we dare say it in these days of gender confusion, Schober's poem is essentially feminine. We oldies, who haven't yet got up to speed on the queer studies thing, find it odd that this horny-handed, rough-hearted killer of anything that moves suddenly wants nothing more than to snuggle up in some chap's arms, possibly that twinky shepherd playing with flowers we were told about, who clearly knows how to give a man a good time. That sort of role reversal comes as a bit of a shock to us straight oldies.

Looking at it another way: take away the hard life and the dead animals and the butch trappings from this poem and we are left with nothing other than a traditional bodice-ripper.

Schubert couldn't rescue this poem. Being honest, we have to say that the rescue attempt brought him down to its bottom-feeding level, too.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!