Du bist die Ruh D 776

Posted by Richard on UTC 2020-02-09 10:04

Does any Schubert fan not like Du bist die Ruh? All the more reason to restrain our enthusiasm for a while and take a close look at its text.

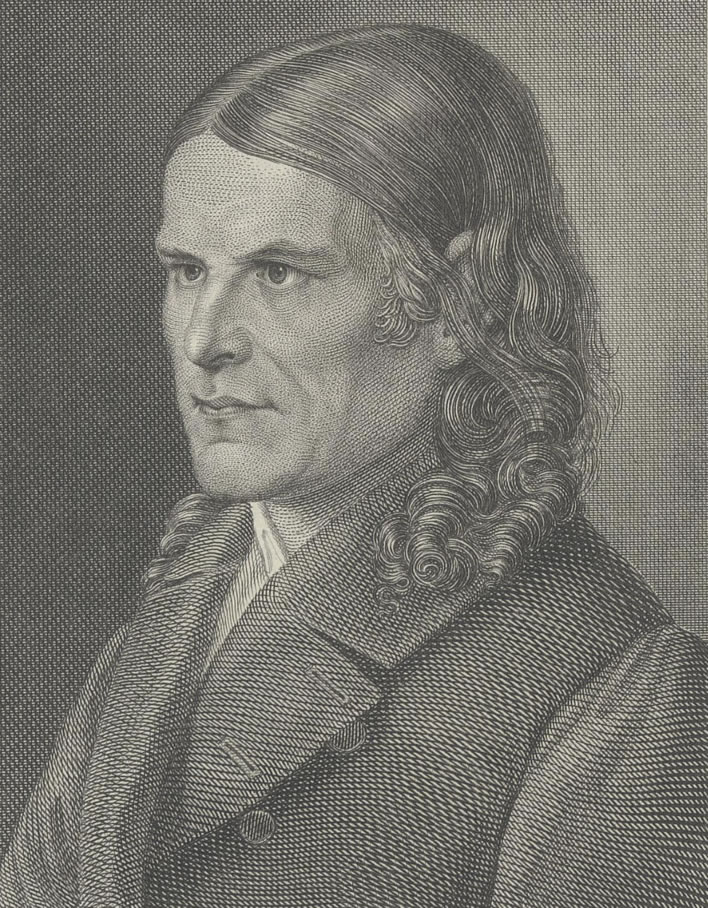

Schubert composed the music in 1823 (the manuscript is lost). The text was taken from a volume of poems by Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), Oestliche Rosen, published by Brockhaus in Leipzig in 1822. In all, Schubert set six poems from this book to music. We presume that Schubert gained access to Rückert's book through his friend Franz von Schober, who had the considerable means needed to stock and maintain a personal library.

Friedrich Rückert (1826) by Karl Barth (1787–1853). Image: Coburg, Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg.

Rückert's poems are always – always: your author can think of no exception – constructed with great poetic artifice. We saw this even in the frantic despair of his Kindertodtenlieder: 563 poems seemingly dashed off, on average three in a day, in a five month long storm of grief, but each one attaining metrical, structural and semantic perfection.

Rückert's brain seems to have been hardwired for poetic expression. Indeed, it has been said of him that he 'thought in verse'. Hegel wrote of Rückert's bewunderungswürdige Gewalt über den Ausdruck, his 'admirable power of expression'.

The surface of the present poem is so beautiful and its vocabulary so compelling that the reader glides over it like a skater over ice:

Ruh, Friede, Sehnsucht, weihen, Lust, Schmerz, Glanz

'calm', 'peace', 'longing', 'consecration', 'desire', 'pain', 'radiance'

Add Schubert's incomparable music and – to be pretentious for a moment – we experience the existential quality of great art, that gesture, that moment of concentration and intensification ('Dichtung'©EzraPound), unthinking, improvisatore (©EzraPound), that culminates in the Gratwanderung, the exhilarating risk of a walk along a mountain ridge, a walk in which one false step can ruin everything, a walk by poet, composer, pianist and singer that takes the listener with it.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau put it as follows:

Franz Schubert transformed a world of poetry into music. He brought the art song to a level previously unknown and showed what all art is: intensification, concentration, cast into its purest form.

Franz Schubert hat eine Welt von Poesie in Musik verwandelt. Er hat das Kunstlied auf eine bis dahin nicht gekannte Höhe geführt und gezeigt, was alle Kunst ist: Steigerung, Konzentration, ein in die reinste Form Gegossenes.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder, Brockhaus, Wiesbaden, 1971, p. 9.

Du bist die Ruh', Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Baritone; Gerald Moore, piano; date unknown. SLUB Mediathek.

Let us put the music to one side and read the poem carefully, in order to look more closely at the depths over which we normally skate.

Text analysis

Title

| — | [Rückert 1922, no title] |

| Du bist die Ruh | You are the calm [Schubert 1823] |

| Kehr' ein bei mir | Come to my dwelling [Rückert 1834] |

Rückert gave none of the poems in his 1822 collection Oestliche Rosen a title. The 'roses' in the collection are grouped in three Lesen, 'gatherings' or 'harvests'. A moment's reflection will tell us that giving the individual roses in these harvests their own names would have been counter to the spirit of the collection.

Rückert was as much a poetry machine as Schubert was a song machine: bang it out and move on. In our study of Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder we compared Rückert's manic but therapeutic writing of poetry about his bereavement to the journal of a modern mood-blogger. Only a few of the 563 poems in that work were given titles.

Schubert, of course, could not publish a song without a title, so for the texts he took from Rückert's Oestliche Rosen he had to be inventive. In the present case, using that traditional method of composers in this situation, he took the first line: Du bist die Ruh.

This title has a great influence on the mood in which readers and listeners approach the work. Unfortunately, the mood of calm that is set in the first stanza and reflected in this title is not representative of the poem as a whole, as we shall see. Schubert's title is not a misfortune, but it is not a blessing either, if we want to understand Rückert's poem.

All the poems in Rückert's 1834 edition of his collected poems were given titles, even those in the Oestliche Rosen. The metaphor of gathered – nameless – roses now no longer needed to be maintained. He titled the present poem Kehr' ein bei mir!, which has quite dramatic implications for our understanding of the meaning of the poem, as we shall see.

Stanza 1

| Du bist die Ruh, Der Friede mild, Die Sehnsucht du, Und was sie stillt. |

You are the calm, the gentle peace, you are the longing and that which quenches it. |

A side effect of Rückert's poetry is that he tests the translator's ability to breaking point and beyond. No 'elegant' or 'poetic' English translation of this poem is possible – the translator who attempts that feat will necessarily violate the complexity of the German original in some way.

There is no way around, for example, Rückert's nominalisation of the abstractions die Ruh, 'calm', der Friede, 'peace' and die Sehnsucht, 'longing'. These all follow the copula bist, 'are', listing these as facets of du, 'you'. 'You' personifies (incorporates or embodies) these abstractions – following this 'are' we have no option but to write of 'the calm' etc. to force the noun in preference to the adjective. The resulting English may not be beautiful, but at least it is accurate.

The translator also has to find some way of rendering Rückert's beautiful phrase Die Sehnsucht du with which he elegantly elides bist: Die Sehnsucht [bist] du.

The translator then has to cope with the power of Rückert's use of stillen, which in its core meaning has all the pedestrian echoes of 'satisfy', 'alleviate', 'quench', 'slake'. But stillen is also the quite normal, everyday verb for breast-feeding a baby – now there's contentment! Then on top of this ambiguity we also hear the echoes of the German still, 'quiet', 'silent' (as, of course, in Stille Nacht…). Stanzas, phrases and words all polysemic, demanding our attention and concentration – but that is Friedrich Rückert's poetry for you.

Layers of meaning in a stanza of four lines, fourteen words in all, four of which rhyme – a stanza so compact and integral that no word can be changed, added or deleted without destroying it. We are in the presence of a language genius of a similar stature to Goethe, who, we noted, achieved a similar laconic triumph in Wandrers Nachtlied II, another poetic masterpiece which brought out the very best in that lyrical master, Franz Schubert.

Standing back from the detailed semantics of this stanza, we ask: what does it mean? The answer is easy: we have here a definition of the loved one as personifications of calm, peace, longing and consummation. Lines 1 and 2 specify the combined property of calm and peace, then lines 3 and 4 define the dynamic process in the skilful opposition of Sehnsucht, the 'longing' of which the loved is the cause as well as its resolution in stillen – the peace and contentment of the breastfeeding child, which she also brings.

Stanza 2

| Ich weihe dir Voll Lust und Schmerz Zur Wohnung hier Mein Aug' und Herz. |

I, full of desire and pain, consecrate my eyes and heart to be your dwelling. |

Rückert's syntax in this stanza is clear but complex. The stanza consists of a single sentence with no punctuation apart from the final full stop. This means that its components are all bound together with an internally referential syntax. As a result, it needs a bit of unravelling if it is to give up its meaning, probably even for native speakers of German, too. Let's take it step by step.

Firstly, weihen has a religious flavour. It means to 'consecrate', 'dedicate' or 'bless' something: the Host, candles, an entire church, your new Lamborghini, those slick Louboutins etc. Weihrauch, incense, is literally 'consecration smoke'.

In the poem, the object being consecrated is Mein Aug' und Herz, 'my eyes and heart'. The singular, das Auge, is frequently used for 'eyes' (in English, too, as in 'more than meets the eye').

The consecration and dedication of a church, die Kirchweihe, is done to the honour of a saint, the verb weihen requires that the honoured one takes the dative, e.g.: die Kirche ist dem heiligen Zeno geweiht. The situation in the poem is an exact analogue, the dedication of the eyes and heart is done in honour of dir, the dative form of 'you': Ich weihe dir … Mein Aug' und Herz, 'I dedicate my eyes and heart to you'. The eye and heart, being the objects of the consecration, are in the accusative but, being both neuter nouns, carry no case terminations.

Zur Wohnung hier is then an appeal to this 'you' to 'take up residence' in the eyes and heart that have been consecrated for this 'you'.

Stanza 3

| Kehr' ein bei mir, Und schließe du Still hinter dir Die Pforten zu. |

Call in on my dwelling and close the gates quietly behind you. |

This stanza contains the crux of the poem. Rückert's later use of its first line Kehr' ein bei mir! as the title of the poem is a clear indication of the importance of this stanza. This is the moment where the loved one, the antidote to all pain and longing, enters the poet-narrator's dwelling.

We pedants cannot help adding that the verb einkehren in German means 'call in on me', 'pay me a visit'. Very prosaically, it might be used by someone on a walk who 'pops in to' a pub on the way. It does not mean to come and stay permanently, to take up residence, as it were. It is an invitation to an erotic tryst, not a marriage. Once the longing has been stilled, the next bus will be along in five minutes.

That entry is amorously charged, but obliquely, in a way no censor and no demure female reader of a literary almanac for ladies (one of Rückert's main sources of income) would find offensive. 'Close the gates quietly behind you' says it all.

It follows that the gates will be open and ready for her arrival, in the best manner of the amorous Roman poets of the first century BC such as Catullus and Propertius.

The fact that these gates may not be real is an extra coat of censor-repellent – they may simply be the metaphorical entrance to the metaphorical dwelling of the eyes and the heart described in the preceding stanza.

However, at 'close the gates quietly behind you', books would be lowered on to laps, the gaze would be distant, unfocussed, perhaps there might even be a slight blush, for even the daintiest, most chaste female hearts, now fluttering, would know what that meant.

We sad souls cursed with metaphoric minds think of gates, doors and thresholds as transitions between states. Our cheeks may not blush at this thought, but the idea of a transition in this case may flutter our hearts a little bit, particularly when the bolt is slid to and the transition becomes finality.

Stanza 4

| Treib andern Schmerz Aus dieser Brust. Voll sey dies Herz Von deiner Lust. |

Drive all other pain from my breast. May this heart be filled with your passion. |

Our worldly readers really need no further comment on this stanza. The use of sey, an old spelling of sei, the imperative form of 'to be', should be noted. The lines might be more simply translated as 'fill this heart with your passion', but that is not quite what Rückert wrote. The logic of the stanza is complete: the other, quotidian, pains will be driven out and their place taken by the 'passion' of the loved one. Modern vulgarians might think of the phrase 'turn me on', which comes pretty close, in fact.

Many pencil ends have been chewed by translators wondering how to represent Lust in English. In German it occupies a spectrum of meaning which ranges from an innocent inclination to raging carnal desire, which is part of its attraction for the poet needing plausible deniability in an age of censorship. Readers will have to choose the flavour of this Lust which suits them.

Stanza 5

| Dies Augenzelt Von deinem Glanz Allein erhellt, O füll' es ganz. |

The tent of my eyes is lit up with your radiance alone, O fill it completely. |

Augenzelt. What a strange word! In the everyday world of German Augen is 'eye(s)', Zelt is 'tent'.

The word is not completely unknown: German apothecaries of the eighteenth century would know of Augenzelt ( a.k.a. sief album, 'white drops') as a potion for böse Augen, 'angry eyes'. But this context helps us not a bit.

This poem is an homage probably to the works of the Persian mystical poet Mevlana Rumi (1207-1273, one of his many name variants). Since the present poem is not a translation, we can expect no direct source for it in Rumi's voluminous writings in Persian (=Farsi).

It is possible that in Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall's Geschichte der schönen Redekünste Persiens (1818), which was one of the stimulations that brought Rückert to Persian and which contains a whole chapter on Rumi with translations of his poetry, there is some precursor text for or allusion to Augenzelt, but your author has not found it.

It is even today a matter of some uncertainty which of the two great Persian poets, Hafez (1315-1390) or Rumi (1207-1273), played the greater part in Rückert's creation of the poems in the Oestliche Rosen. Since the poems in that work are not translations of Persian originals it is pointless to try and work out which Persian poet's work was in Rückert's mind when he was writing any particular poem.

Until the dove of philology descends upon our minds, bringing some solution, we have chosen to interpret Augenzelt as the tent, sanctum or tabernacle of the eyes, which is the mystical place in which the loved one will abide, according to the second stanza.

This solution is not completely unfounded, for there is some authority for it. There is a truly magnificent poem in Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder, Sie haben dir die Augen Vergessen zu schließen in which Rückert gazes into the dead but as yet unclosed eyes of his newly dead daughter and believes to be able to see her soul, as though through the windows of a house:

And still see with my soul's eye a shimmer from your soul.

Und sehe noch immer / Im Auge meiner Seele / Von Seel' einen Schimmer.

She, too, he imagines, takes one last look at him 'before she completely leaves the house, that is now too weak for her'. This transcendental vision is quite in keeping with the Sufic mysticism of Rumi's poetry, the philosophical environment for the present poem.

We mustn't let this conundrum distract us from the erotic magnificence of this last stanza. The tent is filled with the radiance of the loved one allein, all on its own – that is, there is no other source of light: these two are alone in the dark. Just don't tell the censor. Rückert's female readership know it already, however, there is no need to tell them anything.

Structure overview

Let's summarise the structure of the poem:

- Stanza 1: The essence of the loved one. The promise of the consummation of longing resulting in calm and peace.

- Stanza 2: The consecration of the eyes and the heart as a residence for the loved one.

- Stanza 3: The entry of the loved one. Passing through the gate.

- Stanza 4: The loved one as balm for a soul in pain.

- Stanza 5: The sufficiency of the loved one and the total submission to her.

A glance at this simple list will show just how important the role of stanza 3 is. It is the central hinge around which the poem is organized: before this line we have the preparations for the union, after this line the consummation of the union ('O fill it completely'). Stanza 3 thus moves us from one state to the other. It is no mystery why Rückert chose the first line of this stanza as his title of the whole work.

Much more could be written on the technical brilliance of Rückert's poem, for example, his masterful handling of a rhyme scheme in extremely short lines. The only thing we really need to discuss, because it is important for Schubert's setting and particularly for those who want to sing the work, is the flow of the verse through enjambements and caesurae.

Rhythm, enjambements and caesurae

Let us rewrite the lines to reflect the use of enjambement and caesura. (The author is aware that he has gone beyond the strict definition of the term 'caesura' here, but finds it the least-worst term in this context.)

Du bist die Ruh,

der Friede mild,

die Sehnsucht du,

und was sie stillt.

Ich weihe dir voll Lust und Schmerz zur Wohnung hier mein Aug' und Herz.

Kehr' ein bei mir,

und schließe du still hinter dir die Pforten zu.

Treib andern Schmerz aus dieser Brust.

Voll sey dies Herz von deiner Lust.

Dies Augenzelt von deinem Glanz allein erhellt,

O füll' es ganz.

The flow of Rückert's verse differs from that of Schubert's setting at a number of points. Schubert's setting had to be compact and singable – meaning essentially that the performer needs to be allowed oxygen from time to time. The differences are not easy to spot, since Schubert's music is so dominant in our minds.

Rückert's text demands, for example, that stanza 2 should be treated as a continuum. There is a reason that the stanza has no punctuation except at its end, because grammar and syntax requires that there should be no separation between the elements of each line. Which singer can manage this slow legato line in one go, without surfacing for air? Schubert has built in a caesura between lines 2 and 3, which is a reasonable compromise. Singers should not take liberties with this caesura, however – the briefer and lighter the better.

Schubert has allowed the four end-stopped lines of the first stanza to influence the phrasing for the music of the stanza 3.

However, a sensitive reader of the text will probably acknowledge the comma at the end of line 1 with a caesura, but will read the remaining lines as a continuum with two enjambements.

It is interesting that Rückert not only took Kehr' ein bei mir as his title for the poem, as already discussed, but added an exclamation mark to that title. It is, after all, an urgent request to the loved one – the final 'e' of kehre ein is required to render the imperative mood correctly in German (although this requirement is not as strict these days). The syllable has been removed for metrical reasons but is still signalled by the apostrophe, kehr'.

Biographical context

Using the poet's biography as a tool in the analysis and interpretation of his or her work is a dangerous pastime. It is more likely to lead us to false conclusions than greater insights. Nevertheless, Rückert's Oestliche Rosen belongs to a particular period of his life, the four years from 1818 to 1822.

For the first part of 1818 Rückert, then twenty-nine years old, was in Rome, broadening his horizons with the help of the German artist colony there.

Rückert in Rome in 1818. Friedrich Rückert (1818) by Franz Theobald Horny (1798-1824).

Rückert in Rome in 1818. Friedrich Rückert (1818) by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872). Image: Akademie der bildenden Künste, Grafische Sammlung, Vienna.

In October 1818, on the way back from Rome, he stopped off in Vienna, where he met the Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856). By that time, Hammer-Purgstall had become the principal literary channel in German between Europe and the Middle East. His first translation Diwan des Hafis aus dem Persischen (1812-1813) had inspired Goethe to write his West-östlicher Divan, which he began in May 1814 and published in 1819.

Goethe knew no Persian, but transmitted into German the spirit of the poetry of Hafez as he understood it from Hammer-Purgstall's literalist translations.

At the moment that Rückert turned up, Hammer-Purgstall had just published his Geschichte der schönen Redekünste Persiens (1818), which contained an extensive section on the Persian mystical poet Mevlana Rumi (1207-1273). Under Hammer-Purgstall's guidance, Rückert, an outstanding linguist, began his study of Persian and Arabic. At the beginning of 1819 Rückert returned to the parental home in the village of Ebern (northern Bavaria).

It was during the following year, 1819, that Rückert wrote Oestliche Rosen (published 1822). He moved from the small village of Ebern to the town of Neuses, near Coburg, at the end of 1820, where he took a small apartment in the house of the public archivist, Albrecht Fischer (1764–1836).

Rückert and Fischer's daughter, Luise (1797–1857) fell in love. The couple married on 26 December 1821. Rückert was thirty-three, Luise twenty-four. Luise came into Rückert's life too late to be an influence on the Oestliche Rosen, but their love affair inspired him to write a collection of poems he called Liebesfrühling (published in various magazines 1822-24, then in the Complete Works of 1834).

In Liebesfrühling we find a number of poems in which he uses the poetic materials he had collected in Oestliche Rosen, here, for example.

| Du meine Seele, du mein Herz, Du meine Wonn', o du mein Schmerz, Du meine Welt, in der ich lebe, Mein Himmel du, darein ich schwebe, O du mein Grab, in das hinab Ich ewig meinen Kummer gab. Du bist die Ruh', du bist der Frieden, Du bist der Himmel mir beschieden. Daß du mich liebst, macht mich mir wert, Dein Blick hat mich vor mir verklärt, Du hebst mich liebend über mich, Mein guter Geist, mein beßres Ich! |

You my soul, you my heart, you my bliss, O you my pain, you my world in which I live, you my heaven in which I float, O you my grave in which I give my eternal grief. You are the calm, you are the peace, you are the heaven given to me. That you love me makes me worthy to myself, your gaze has transfigured me to myself, you rise lovingly above me, my good spirit, my better I! |

Friedrich Rückert, 'Du meine Seele, du mein Herz' in Liebesfrühling: Werke, Band 1, Leipzig und Wien [1897], S. 141-142. Online at Zeno.org.

Despite the similarities, though, there is an essential difference between the poems of the Oestliche Rosen and those of the Liebesfrühling: The former are suffused with the mystic eroticism of the original, made palatable for the Biedermeier taste with delicate complexity; the latter move on a spiritual plane, an elevated Platonism.

At the centre of Kehr' ein bei mir there is an invitation to a moment of erotic fulfilment, a physical consummation metaphorically expressed; in Du meine Seele, du mein Herz we find a Platonic adoration of the immaculate Lady that Dante would not have found out of place for his Beatrice.

Luise Rückert as a bride, 1821, by Karl Barth (1787–1853). Image: © Literaturportal Bayern.

Altogether the Rückerts had ten children in relatively quick succession – the income from the success of Oestliche Rosen and his publishing activity in many of the almanacs of the day were important factors in putting food on the table for this brood.

He was still a 'private scholar', supplementing the support he received from his parents and grandparents with whatever he could earn from his writing. However, in 1826 his translation studies gained him a professorship for oriental languages at the University Erlangen, which provided a welcome fixed income. Rückert and Luise were a devoted couple until her death in 1857.

Friedrich Rückert (1843) by Samuel Friedrich Diez (1803-1873). Image: ©Foto: Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Fotograf/in: Atelier Schneider.

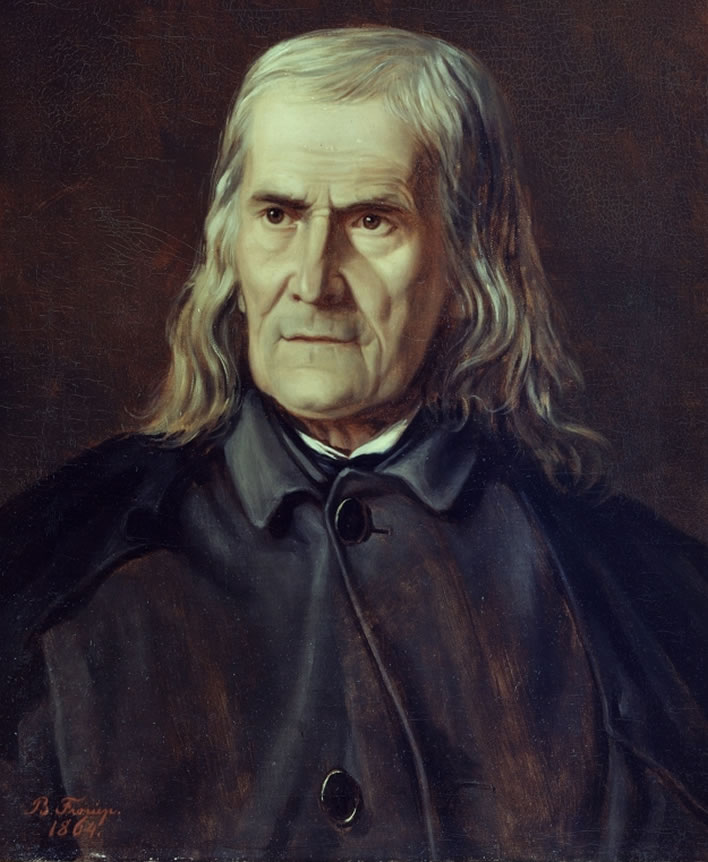

Friedrich Rückert (1864) by Bertha Froriep (1833-1920). Image: © Foto: Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Fotograf/in: Christa Begall.

We Schubert fans have a game we like to play. Rückert was thirty-one when he wrote Oestliche Rosen and had another forty-seven years of productive labour ahead of him. At thirty-one, Schubert was dead.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!