Franz Schubert's Mensch

Richard Law, UTC 2019-05-13 08:42 Updated on UTC 2019-05-14

On recovering Schubert

Nearly a year ago I wrote a piece about the first of Franz Schubert's two summer stays with the Esterhazy family on their country estate in Zseliz, in (now) Slovakia, in 1818. That period may not have been terribly important musically, but it is of crucial importance for Schubert studies.

This importance arises from the fact that the letters written by Schubert to his family and friends during this stay are among the documentary crown jewels of the Schubert biography: they are some of the very, very few instances where we find the authentic voice of Schubert in relaxed and unguarded conversation with his family and friends.

The Schubert biography is stuffed full of the more or less imaginary recollections of those who more or less knew him and who more or less remember things they finally set down thirty years or more after the poor chap became a decomposing composer at the end of 1828. In contrast, in those letters written in Zseliz, we encounter the lively 21 year-old as his friends and siblings knew him, a young man still largely free of the problems that would beset him in the ten years or so that remained to him. We read those letters and imagine that we can hear him speaking these words, so fresh they sound, so uninhibited and so intimate.

The letters are written mainly to friends and to his brothers and so give us a glimpse of the shared culture and the group dynamics among these young men. The modern reader becomes party to this conversation in which almost every sentence is revealing in some way. We overhear this conversation – but do we understand it fully?

Fully? Almost certainly not.

The distant country

We are foreigners adrift in this distant country of early 19th century Vienna, where they not only do things differently but also think in different ways to us. Some things within the narrow confines of our understanding we may easily grasp or work out, but we are ultimately in a similar position to that of a freshly graduated student of German sitting for the first time at a Viennese (or Bavarian or Swiss) Stammtisch: Bahnhof!

Even if we 'understood' the words we hear, we do not really understand them because we have no idea of their cultural and semantic context – their back-story, if you will – or the affect behind their use.

As we listen in and study, over the years we understand more and more, but never completely. Strangers should never succumb to the arrogant belief that they fully understand people with whom they haven't grown up, or with whom they haven't been to school. One simply never knows enough.

How much truer this is of the distant country that is early 19th century Vienna. It is hazily distant for modern native speakers of German in accordance with their language flavour – Austrian, German or Swiss. Of course Austrians – more specifically Viennese – have an advantage here with which natives of other German dialects cannot compete, whereas non-native speakers of German can barely make out the fuzzy outlines of this distant culture, lost in the mist of 200 years.

These important letters between Schubert, his friends and his siblings emerge from this mist to confront us with many unknowns. On several occasions we can say we understand what he has written, but often with more hope than conviction and only in the most facile, superficial meaning of 'understand'. For the translator the situation is much worse: even if he or she 'understands' the original, there remains the search for some equivalent in English – le mot juste – that will transmit the meaning into some form of words that will be understood in all the many current flavours of this world language.

In my translation of one paragraph of those letters I went catastrophically wrong: a combination of incompetence, ignorance and haste proved to be my undoing. I am not going to repeat this mistranslation here: I don't want some search engine to perpetuate the nonsense but – yes, readers have guessed it – really I'm just too embarrassed.

Fortunately, Rina Furano, a Viennese composer, stumbled over my idiocy and was kind enough to write to me and point it out with fitting forcefulness. However, the repair of this translation turned into a philological adventure involving a number of native German and Austrian speakers, an adventure that illustrates well the difficulty of recovering meaning that we moderns can understand from that distant country of Schubert's life and times.

It is fair to say that in this particular adventure I received as many differing interpretations as there were people interpreting – a fact which, in itself, was extremely helpful.

…how shall philologers?

[…]

Shall two know the same in their knowing?

Ezra Pound, The Cantos, C93:631.

These letters are important and rare artefacts from that distant country: it's worth trying to understand them in every detail.

Schubert in church

The text that brought me down occurs in a letter Schubert sent to his brothers (explicitly not intended for his father's eyes – a fact which is in itself luminously meaningful) from Zseliz dated 29 October 1818. Here it is with our current English translation. The contested section of the text is in bold:

You, Ignaz, are quite the old scrap-iron man. Your unforgiving hatred of the tribe of clerics is a testament to you. But you have no idea of the clerics around here, bigoted as an obstinate old animal, stupid as a donkey and coarse as a buffalo. You listen to sermons here that are worthy of the greatly revered Father Nepomucene. It is a pleasure to listen to the denunciation of sinners and wrongdoers from the pulpit here. The preacher brings a skull up to the pulpit and says: 'Look at this you pustulent crapfaces, this is how you will look one day.' Or: 'A youth goes into the tavern with a slut, they dance the whole night, then the two of them lie down drunk and when they get up in the morning there are three of them.' etc.

Du, Ignaz, bist noch ganz der alte Eisenmann. Der unversöhnliche Haß gegen das Bonzengeschlecht macht Dir Ehre. Doch hast Du keinen Begriff von den hiesigen Pfaffen, bigottisch wie ein altes Mistvieh, dumm wie ein Esel, u. roh wie ein Büffel, hört man hier Predigten, wo der so sehr venerierte Pater Nepomucene nichts dagegen ist. Man wirft hier auf der Kanzel mit Ludern, Kanaillen etc. herum, daß es eine Freude ist, man bringt einen Todtenschädel auf die Kanzel, u. sagt: Da seht her, ihr pukerschäkigten Gfriser, so werdet ihr einmahl aussehen. Oder: Ja, da geht der Bursch mit'n Mensch ins Wirtshaus, tanzt die ganze Nacht, dann legen sie sich besoffen nieder, u. stehen ihrer drey auf u.s.w.

[Dok 75]

In order to understand the complex background to the dislike of Roman Catholic clerics shared by the brothers Franz and Ignaz Schubert (Ferdinand was not so forceful) you should read Ignaz's letter to Franz to which this is a response.

Behind this conversation there is a more general historical background, which we covered in some detail in the Zseliz article, but which we can summarise here.

The clergy and the teachers

The Austrian school system at the time was firmly under the control of the Catholic Church. Up until 1773 education in the Habsburg Empire had been in the hands of the Jesuits. In that year the Empress Marie Theresia and her Co-Regent son Joseph II (who always liked to consider himself a child of the Enlightenment, despite his own leanings to authoritarianism and despotism) suppressed the order.

Schubert's father was in the middle of his education at a Jesuit Gymnasium in Brünn at that moment. There were a few years of confusion and improvisation after the Jesuits had been removed, but on the whole, educational matters went on as before – there was no one to replace the teachers or their textbooks at such short notice. Gradually other religious orders took over the task of running the schools.

The rich hired tutors for their little ones, teachers who could bring the tots up in accordance with their employer's wishes. The less well-off paid a local school to do the job, a school such as father Schubert's school in Himmelpfortgrund. Such schools were always under religious control. Always. The powers-that-be fought a continuing campaign against so-called Winkel-Schulen, 'corner schools' (we might call them 'pop-up schools' nowadays), small, unregistered schools run by enterprising spirits outside clerical control. The authorities caricatured these corner schools as being run by money-grubbing incompetents and scammers – whether justly or not, I do not know.

Schubert received his elementary schooling in his father's school then was sent to a Viennese Gymnasium run by the Piarist order and boarded at the Stadtkonvikt. Despite all attempts at reform and the imposition of standards, as already noted, schools in Austria were ultimately under the control of the local religious establishment. It was against the arbitrary despotism of an hierarchy which reached from the local priest upwards through all the levels of church administration that the teachers in the Schubert family, father Franz, brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand and, to a much lesser extent, the humble assistant teacher Franz Schubert had to struggle.

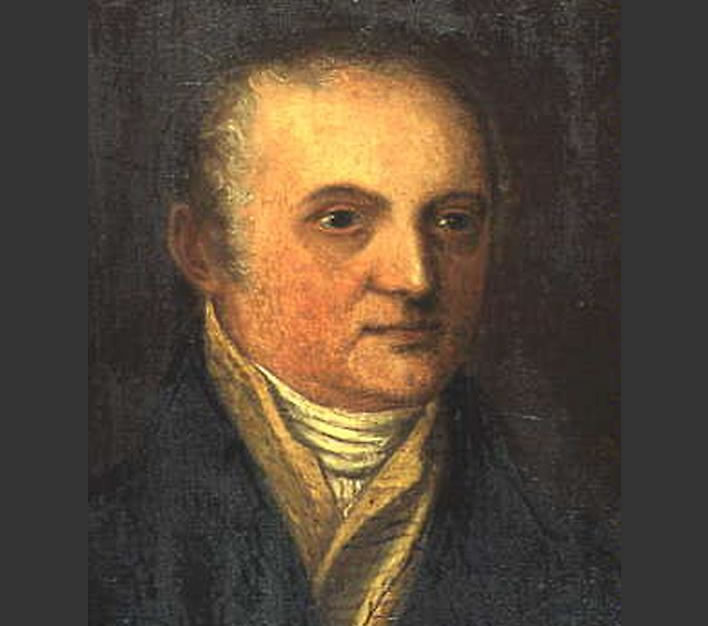

Franz Theodor Schubert. Unknown artist, unknown date.

Schubert's father, Franz Theodor, was the son of an extremely pious Moravian farmer and had Jesuit obedience, obeisance to authority and diligence hammered into him, traits that served him well during the drudgery of his ascent from penniless auxiliary teacher to become the esteemed director of his own school. We note that Franz Theodor named both of his first sons Ignaz, after Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. Clerical patronage was involved in getting father Schubert his first school in Himmelpfortgrund and in obtaining his post at the Rossau school. Patronage drips on the soul as water on a stone until the stone and the soul are no more.

In his youth, though, Franz Theodor had displayed some early opportunism and free thinking. He and Elisabeth Vietz brought a child, Franz Ignaz Vietz, into the world out of wedlock, a child who lived only two weeks before meeting his end in the bacteriological incubator that was the Foundlings' Hospital in Vienna. Their second son, the Ignaz of our tale, was present at his parents' wedding as a seven-month old embryo. From the letters of the siblings we get the impression that despite all Franz Theodor's early sexual buccaneering, by the 1820s he had (or had had to) become an associate member of the hierocracy with all its prudish traits.

Walls have ears

Well, we all get a bit grumpy as we get older, but Franz Theodor's position depended existentially on his keeping his nose clean for his clerical minders. The last thing he wanted was anyone in his family upsetting the boat with speech or deed. Thoughts – well, as far as thoughts were concerned you could think what thoughts you liked in Austria at that time – just don't speak them aloud and certainly don't write them down.

The Habsburg emperor of the time, Franz II/I, a frightened and unsure personality under whose repressive belljar they all lived, was particularly attentive to making sure that schools and universities did not spread dangerous revolutionary ideas.

Teachers and students at whatever level who strayed from orthodoxy were disciplined quickly and aggressively. The anecdote at the link dates from 10 September 1810, only eight years before Schubert's first Zseliz visit. We should also remember that less than two years after Schubert's stay, his great friend Johann Senn was arrested, mistreated and ultimately exiled to the Tyrol on suspicion of student activism.

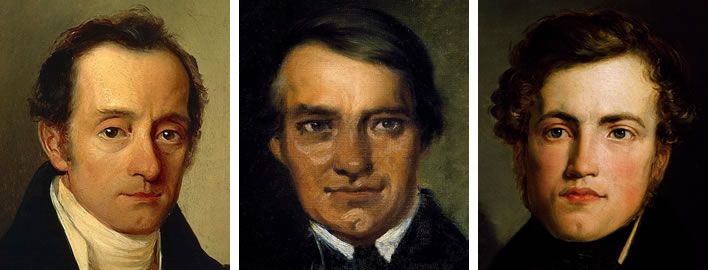

Franz Peter's three brothers (dates unknown). Left: Ignaz. Middle: Ferdinand, from an unfinished self-portrait – the 'Schubert dimple' was a challenge. Right: Karl. Image: Wien Museum, Schubert Geburtshaus, Nußdorfer Straße 54, 1090 Wien.

Thus in this anti-clerical part of their letters the brothers are entering dangerous territory. But their shared detestation of the clerical hierarchy was nevertheless set down on paper – a testament to their strong family bonds and their mutual trust.

As a gesture of agreement with his brother Ignaz's anticlerical stance, Franz supplies his own independent evidence to reinforce his brother's opinion. The passage in Schubert's letter to Ignaz reproduced here leaves no doubt that Schubert was as anticlerical as his brother – the only difference being that as a schoolteacher, Ignaz was confronted with the problem almost every working day. Franz, now largely free of school-teachering, could just ignore the problem and get on with his composing. So far, so good. But what do Franz's words in his letter mean and how can they be translated into an English that a modern speaker would understand?

Speaking to the flock

Centuries of ministering to the illiterate and unlettered masses have taught the lower orders of the Catholic clergy to speak to their flocks in language they can understand.

In the great towns and in cities such as Vienna or Prague, on the other hand, preachers could allow themselves elevated language and refined conceptions.

During the Broschürenflut, the 'pamphlet flood' that broke out shortly after the beginning of Joseph II's sole reign in 1780, when the 'enlightened emperor' decided on one of his whims to allow his subjects free speech in print (in the Zensurgesetz, 11 June 1781), many of the ephemeral flysheets commented and attacked sermons in particular. The bishops and priests grumbled at Joseph for allowing their sermons to be criticised in public, but the anti-clerical emperor found this side-effect of his new law not unpleasant.

Until, that is, the leaflet-printing rabble then turned on him, causing him to withdraw that enlightenment freedom of expression finally in December 1789, not long before his death. By the time Franz II/I became emperor in 1792, all this freedom of printed speech nonsense had been placed in the dustbin of history and would remain there for more than fifty years.

Such criticism and discussion contrasts with the situation in the illiterate agrarian communities, where the common people's lack of language skills and analytical ability meant that they could not do this – every Sunday and feast day the congregation, largely an unlettered peasantry, just had to sit there and take whatever instructions the cleric doled out to them. That is, unless a Viennese composer was sitting amongst them. It is in this context that we have to understand Schubert's particular revulsion for the words of the preachers in Zseliz.

Perversely, this reflex of dumbing down when speaking to the rabble was a habit that made clerics very ineffective as elementary school teachers in the days when they were expected to teach the rural poor. Their sights were set low and their techniques appropriately so – usually just rote learning of the catechism and third-hand religious sayings. In doing this they became to some extent the enablers of illiteracy.

We shall spare readers the essay on the beginnings of literacy teaching under the Protestant churches, who set themselves the much higher goal of getting their flocks to read the Bible for themselves. We note only that, when the Catholic authorities in Austria finally decided to get serious about the education of the people, it was to the Prussian Protestant schools to which they turned for their models of textbooks and curricula.

Franz Schubert had never been outside Vienna before his stay in Zseliz, let alone outside Austria. Suddenly he experienced the true nature of the rural sermon. Ignaz may have found something like it in the Viennese Vorstadt, but even that would have found some modulation compared to that which his brother Franz now heard in Zseliz, a rural location remote from the towns and cities of the region.

Ihr pukerschäkigten Gfriser

In his letter to Ignaz, Schubert mocks the coarse language of the local preachers. Whether the examples he gives for this coarseness are real or not – well, only Franz knows that and he is currently unavailable for comment. The first piece of vulgar clerical invective comes in the phrase ihr pukerschäkigten Gfriser.

Well, even the most slow-witted translator realises that this phrase is not intended as a compliment, so really any insults will do, but let's try and be a bit authentic. The adjective schäkig, more usually written scheckig means 'checked', 'variegated' or perhaps the rather poetic 'dappled'. Given the level of invective in the statement, we might also consider 'blotchy', 'mottled' and similar unpleasant words.

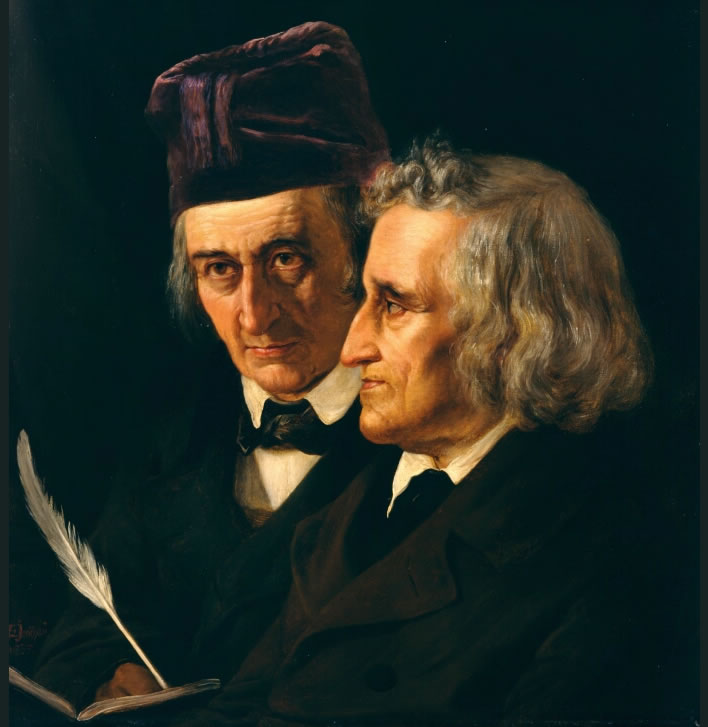

The decision is made easier when we restore the prefix puker: pukerschäkig is Schubert's dialect variant for pockenscheckig, 'pockmarked'. The Duden and the Deutsches Wörterbuch from Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm prefer pockennarbig.

Gfriser is the plural of the word Gfris, present with small orthographic and tonal variations in Austrian, Bavarian and Swiss dialects in the meaning of 'face'. The word is not a dainty one – in modern English one might say 'gob', 'chops' or 'mug'; the modern German might say Fresse. For our translation we invented the phrase 'pustulent crapfaces', since the semantically more accurate 'pockmarked mugs' would present most English speakers with parsing problems.

Whether Schubert's text is an accurate reproduction of a sermon or a parodic invention of Schubert himself, the remark 'pockmarked mugs' associated with the skull as the symbol of death is a grotesque insult to the congregation, who cannot help being part of the medical lottery of those times which decided who caught the dreaded smallpox, who died of it and who was left scarred for life. The implication was therefore that a dose of smallpox was the wage of sinful behaviour.

Das Mensch

So far, so easy. Now we come to a greater conundrum: das Mensch.

The word der Mensch that you will find in modern German dictionaries can be accurately translated into English using words such as 'human being', 'person' etc. Everyone learning German knows that one soon enough.

But Schubert's preacher is not using der Mensch here, but the word das Mensch. There is a bigger difference between the two than you might think. Both nouns may be spelled in the same way but they differ not just in gender, but also in declination as well as in meaning. The differences in grammar can be represented in a comparative table. Back to school, children!

Declination

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| Nominative | der Mensch | die Menschen |

| das Mensch | die Menscher | |

| ein Mensch | ||

| Genitive | des Menschen | der Menschen |

| des Mensch(e)s | der Menscher | |

| Dative | dem Menschen | den Menschen |

| dem Mensch | den Menschern | |

| Accusative | den Menschen | die Menschen |

| das Mensch | die Menscher |

In all but one of the numbers and cases the form of the noun das Mensch differs from that of der Mensch.

Der Mensch is a noun which is assigned to the so-called 'weak declination': apart from the nominative singular der Mensch all its forms are written Menschen.

Das Mensch, in contrast, is assigned to the so-called 'strong declination', which gives it a more variable set of endings. The pattern is the same for the much more common noun das Bild, 'the picture', so if the plural Menscher strikes you as odd you should think of Bilder. The red highlighted term draws attention to the fact that with the indefinite article in the nominative there is no way of telling the difference between the two words (unless an adjective is added).

There, all over now. Wasn't that fun? Now you have seen one of the many reasons why German has never become a world language, nor ever will.

In Schubert's rant from the pulpit we note that the phrase is da geht der Bursch mit'n Mensch ins Wirtshaus. Leaving aside the dialect sloppiness of mit'[eine]n instead of mit einem Mensch, we know that das Mensch is meant here and not der Mensch because the latter, as a dative singular, would have to be Menschen, that is, mit einem Menschen, or shortened mit'm Menschen.

But what does das Mensch mean – as opposed to the more familiar der Mensch?

Meaning

Das Mensch emerged in Middle High German, at first with a similar meaning to der Mensch. Whereas the meaning of der Mensch has remained relatively stable down through the centuries, this cannot be said for das Mensch.

The Grimms' dictionary lists with example texts all the nuances through which das Mensch has passed in the intervening centuries. If you are a German speaker and would like the detailed account of this tale you should look up the online entry in Grimm. The following is a summary for English speakers, designed only to show what shifting sands are beneath our feet when we are trying to understand das Mensch. Moreover, meanings persist, fade and overlap, so the reader should not take this list as a strict chronological sequence.

Elisabeth Jerichau Bauman, Doppelporträt der Brüder Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm, 1855.

Those who confidently quote 'meanings' sourced from dictionaries should reflect that the only meaning a word has is that which is in the head of the person speaking it or writing it at that particular moment:

'When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, 'it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.' 'The question is,' said Alice, 'whether you can make words mean so many different things.' 'The question is,' said Humpty Dumpty, 'which is to be master – that’s all.'

Lewis Carroll (Charles Ludwig Dodgson, 1832-1898), Through the Looking-Glass, 1872, chapter 6.

The further meaning of what the hearer or reader understands by this word is another matter altogether. Here we go – only eleven to get through:

- Person: das Mensch kept the meaning of 'person' (with a range of nuances) side by side with der Mensch into the 17th century in the formal language. This usage can still be found in dialects of German into the present day.

- Servant: Around the middle of the 15th century we find das Mensch used very specifically to refer to a servant (whether male or female). P. G. Wodehouse fans will immediately think of My Man Jeeves, etc.

- Female person: Over the three centuries from the 15th to the 18th century the word das Mensch was used to refer to a female person. In the early years this meaning used the weak conjugation and thus can often be scarcely distinguished from der Mensch, but in time the form with the strong conjugation took its place.

- Female jobs: This basic meaning of 'female' was then extended with prefixed words that referred to females in specific roles: dienstmensch. 'maidservant' or küchenmensch, 'kitchen maid'.

- Female person: In the 16th and 17th centuries, das Mensch continued to be applied to females in general and of all ranks, neutrally, with no derogatory connotations, an equivalent of Weib.

- Person with gender specifier: In the 17th and 18th century it was also possible to apply das Mensch to females and males alike as long as some word was present that made it clear which was meant.

- Female servant: At some point, the meaning of 'female' and the meaning of 'servant' coalesced to give das Mensch with the specific meaning of 'female servant'. The term 'coalesced' may be misleading, since this usage may have arisen by erosion of specific terms, such as those used (as in 4) for female jobs: dienstmensch, kammermensch, kindermensch, küchenmensch, kühmensch, 'serving-, chamber-, children's-, kitchen-, cow-maid' etc.

- Female person, possibly an 'available' woman: In the language of the fields and the villages, das Mensch came to be used for a nubile, unmarried woman. Even the brothers Grimm puzzle over cases where this meaning seems to have taken on a pejorative cast, shading into 'easy' or even 'prostitute'. They speculate that this occurs only when some dealings with men are explicitly involved.

- An 'easy' female person: Where the context that sets the tone of the usage already reveals contempt or scorn, das Mensch focuses this contempt on a female person. The English word 'slut' comes to mind; speakers of British English might also think of the term 'slapper'.

- A man's friend: The Grimms find a particular usage in connection with the word Kerl, a rough and ready type of chap, the perfect partner for das Mensch. English speakers might think of expressions such 'the lad and his lass' etc.

- Prostitute, for money or for fun: Finally there is the usage of das Mensch that implies deep moral laxity, perhaps even prostitution.

The results for das Mensch from the Adelung are much the same, though conciser. A similar exercise in the Schweizerisches Idiotikon also yields similar results. There the range of meanings also stretches from the abstract and ungendered 'person', through many combinations of women and girls, married and single, seductive and repellent, noble and common, mistresses and prostitutes.

Once again, this time in pictures

Young women

Alma Erdmann, Schwarzwälderin (Girl in the costume of the Black Forest), 1899. [Ein Mensch / das Mensch / das Dorfmensch in Schwarzwälder Tracht]

Servants and working women

Vida Lahey, Monday Morning, 1912. [Zwei Wäscherinnen / zwei Wäschermenscher / zwei Wäscherweiber / zwei Dienstmenscher]

Albert Edelfelt, La Laitière (The Milkwoman), 1889. [Das Milchmensch / das Milchweib / die Milchfrau / das Milchmädchen]

Karl Hagemeister, Mädchen mit Milchkanne (Girl with a milk can), 1889. [Das Milchmensch / das Milchweib / die Milchfrau / das Milchmädchen]

Karl Hagemeister, Zwei Frauen im Rübenfeld (Two women in the turnip field), 1885. [Zwei Bäuerinnen / zwei Bäuermenscher]

Daniel Ridgway Knight, An Idle Moment, 1890-95. [Der Schafshirt und zwei Menscher / Dienstmenscher]

Rural couples

Circle Of Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Couple With A Hen And A Spindle, ND. [Bauer und Mensch / Weib]

Man's best friends

Gerrit Van Honthorst, Smiling Girl - A courtesan holding an obscene image, 1625. [Die Dirne / das Mensch]

Hendrick Terbrugghen, A Girl Holding a Glass, 1620s. [Die Dirne / das Mensch]

In the tavern

Wilhelm Leibl, Das Ungleiche Paar (The ill-matched couple), 1876. [Bauer und ein Mensch / ein Weib]

Jan Steen, A Man Blowing Smoke at a Drunken Woman, c1660-65. [Das / ein Mensch]

Fun and games

Jose Jimenez Aranda, The Blind Chicken, c1889. [Die Mädchen / die Menscher]

Simeon Solomon, Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene, 1864. [Zwei Menscher] Image: Tate.

—Chrysander. … One minute he swears that he knows no woman, and now he names half a dozen Menscher. —Damis. Menscher? Father! —Chrysander. Yes, my son, Menscher! … —Damis. Heavens, Menscher! calling famous Greek poetesses Menscher!

—Chrysander. … Den Augenblick schwur er, er kenne kein Frauenzimmer, und nun nennt er ein halb Dutzend Menscher. —Damis. Menscher? Herr Vater! Chrysander. Ja, Herr Sohn, Menscher! … —Damis. Himmel, Menscher! griechische berühmte Dichterinnen Menscher zu nennen!

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Der junge Gelehrte, 1747. [cited in Grimm]

The various dialects set few limits on the meaning or orthography of das Mensch – unsurprisingly, in that dialects, though occasionally written down, are fundamentally oral languages which therefore rely on oral significations of meaning such as the tone of voice. Words that are identical when written can therefore mean very different things, as Humpty Dumpty told us.

Our problem is therefore that when Schubert writes da geht der Bursch mit'n Mensch ins Wirtshaus etc. and we review the eleven usages we obtained from the Grimms, we are forced to admit that any of these usages could apply in the present instance. His brothers and friends would probably know what he meant, but we are a long way outside that circle of intimates.

What to do?

Well we know from the context that here Schubert is quoting or parodying the words of a preacher using words that are extreme or coarse.

It is interesting to remember in this context that Schubert also found Count Esterhazy ziemlich roh, 'quite coarse'. Schubert had a well-developed sense of propriety. Father Schubert and mother Elisabeth had raised their children well; their son Franz's years in the Akademisches Gymnasium and the Stadtkonvikt would have contributed to his undoubtedly highly-developed sense for the nuances of language.

We sometimes read of Franz Schubert as having deep Viennese roots and being a 'man of the people', which may all be true, but he was no vulgarian. The people in his Freundeskreise, his 'circles of friends', were sensitive artists, writers, lawyers and civil servants. Schubert was above all a skilled language craftsman, with a fastidious ear for meaning, nuance and rhythm in language. Particularly in their early years, Schubert and the Circles of Friends were enthusiastic seekers of the sublime and the elevated in thought and art.

But the words we have before us are not Schubert's words, they are the words of a clerical thug ('bigoted as an obstinate old animal, stupid as a donkey and coarse as a buffalo') preaching to his simple-minded congregation, whether real or imagined.

So of the options we have available to us that might have issued from the cleric's mouth, the worst would be no. 11, 'prostitute'. Since no money seems to change hands, though, we can dismiss this immediately.

No. 10, the pairing of the 'young man and his girl' is attractive, but probably too subtle and too kind in this context.

We are left with no. 9, the 'easy' female person.

But then why, you ask, does the man get off lightly with the relatively neutral term Bursche, signifying merely a young man, possibly a tradesman or an apprentice, whilst the girl is a 'slut' for simply doing what he did: going into a tavern with a member of the opposite sex, drinking, dancing and ultimately going to bed with this person.

Well it is undoubtedly the case that the pious choose to view the daughters of Eve as the cause of most of the problems of the world – just as their mother was the cause of all that trouble at the time of the Fall of Man. Chastity is expected of 'nice' girls; boys are expected to take their chances when apples are offered.

Rembrandt, Adam and Eve, 1638.

Thus it is completely appropriate to the thought processes of the bigoted preacher to condemn the girl more harshly than the man: hence, let us opt for 'slut'.

Chasing skirt

If we are still fretting about the misogyny of the village priest in Zseliz, the Grimms' dictionary gives us a helpful tip at the end of the article on das Mensch: vergl. dazu das verbum menschern, 'compare the verb menschern'.

When we do this we find that the verb menschern comes with two meanings. The first 'to smell humans' or 'to smell of humans' is useful for breaking the ice at dinner parties (I don't get asked to many these days – I can't think why).

It is the second meaning that lights up our dashboard:

2) personal menschern (after the neutral mensch 3, column 20137), maintain immoral doings with females. In the Tyrol. Schöpf 433; in Kärnten mentschern make nightly visits to the loved one.

2) persönliches menschern (nach dem neutr. mensch 3, c sp. 2037), mit weibsbildern unsittlichen umgang pflegen. in Tirol. Schöpf 433; in Kärnten mentschern, bei der geliebten nächtliche besuche machen.

Sounds good to me.

The author would like to thank all those people who assisted in this search for understanding in the words of Schubert's preacher in Zseliz 201 years ago, particularly: Rina Furano, Daniel Johannsen, Georg Klimbacher, Rita Steblin, Gerrit Waidelich. They will be delighted to hear that the author bears the entire responsibility for the opinions expressed here.

Update 14.05.2019

Added some images.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!